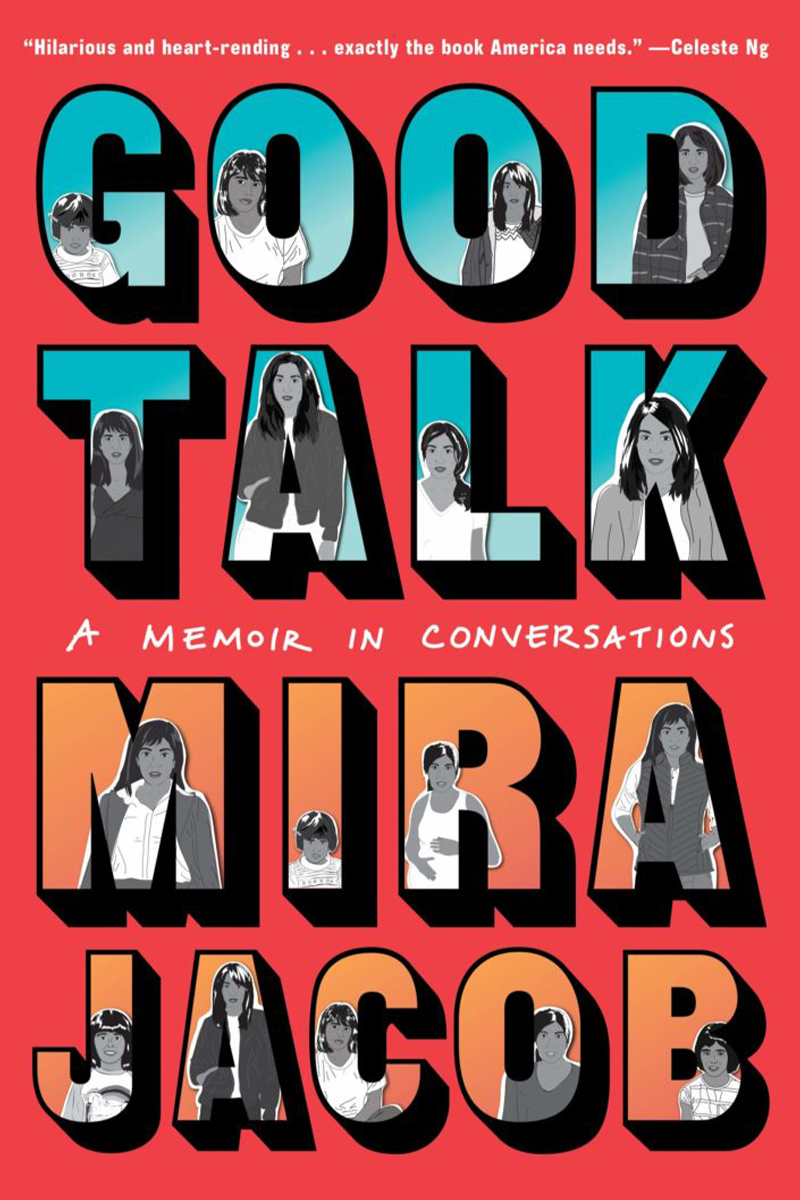

I knew my friend Mira Jacob was a talented writer — her work has appeared in the New York Times Book Review, Literary Hub, Vogue, and Harper’s Bazaar, among others — but in 2019, when her book, Good Talk: A Memoir in Conversations, was released, I was still gobsmacked. Mira taught herself to draw in order to create this graphic memoir, which tackles everything from immigration and discrimination to LGBTQIA+ issues and struggling to belong, even within your own family. At its root, it is a treatise on belonging and quickly became my favorite resource for antidiscrimination work — in fact, I had bought and given away so many copies that when she recently traveled to Houston for a speaking engagement, I begged her to sign my latest copy, “To Karen,” so that I’d be sure to keep it as my own!

I’m not the only person who thinks Good Talk is a masterpiece: The work was short-listed for a National Book Critics Circle Award, long-listed for the PEN Open Book Award, and named a New York Times Notable Book and a best book of the year by Time, Esquire, Publishers Weekly, and Library Journal. In fact, Good Talk is currently in development as a television series with 20th Century Studios.

It’s that good.

When Mira isn’t writing award-winning books, she is an assistant professor at the MFA creative writing program at the New School in New York and a founding faculty member of the MFA program at Randolph College in Virginia. Mira lives in Brooklyn, New York, with her husband, documentary filmmaker Jed Rothstein, and their son.

Photography courtesy of Random House.

Mira Jacob on a trip to Isla Mujeres; photography by Piyali Bhattacharya.

In so many ways, Good Talk is about belonging — in America, in family. Is belonging something you continue to wrestle with? Did the process of writing the book reveal anything to you about belonging?

Whew. Let’s start with the easy stuff, huh? The book is very much about belonging, especially the sharp edges of it, the ones we cross over unknowingly, only to suddenly realize we no longer belong the way we assumed we did. In Good Talk, my unbelonging came in the form of growing up with Indian immigrant parents and then later marrying into a white, Jewish, and eventually pro-Trump family. The ways my upbringing informed my experience with my in-laws was both inevitable and devastating. White Americans get to choose how to align themselves with the racism that favors and values their lives, and I was just so sad to witness my in-laws make a choice that was so harmful for me, my family, and the grandson they adored. I wish I could say belonging is something I no longer wrestle with, but I definitely do. Trump being back in the limelight has made me wonder how much further down this track of losing one another we are all headed for.

The subtitle of your book — A Memoir in Conversations — is intriguing, especially since your book tackles racism, sexism, homophobia, and colorism, among other social issues. Can you share why you chose (a) conversations and (b) a graphic approach to tackle these issues?

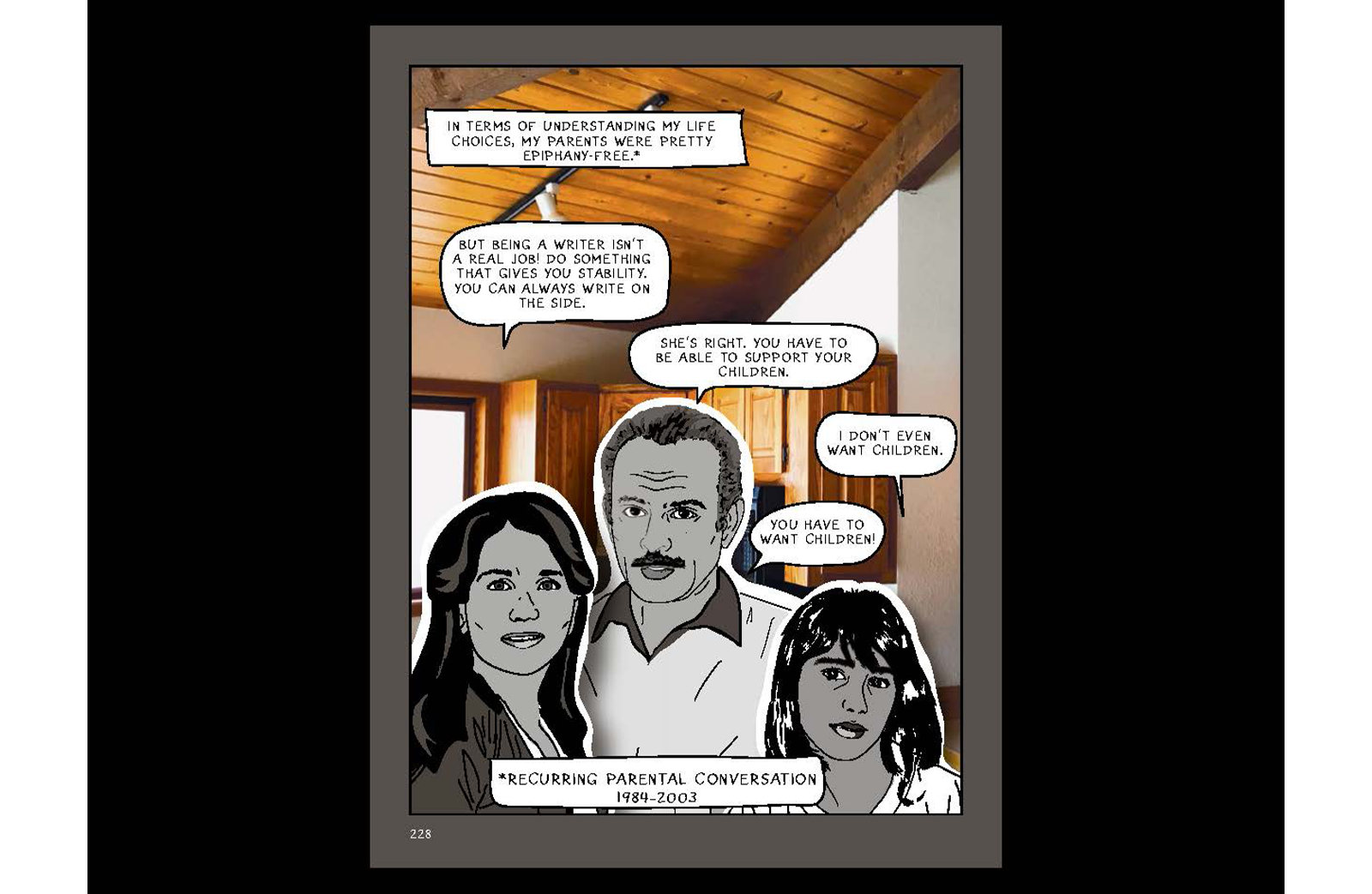

So full disclosure: My publisher came up with the subtitle of the book, and at first glance, I hated it. Or rather, I was embarrassed by it because in my head, memoirs are for people whose lives are spectacular in some way, notable. Meanwhile, what I wanted to talk about was this very unglamorous, hard-to-define thing, which was how beautiful and hilarious and terrible and heartbreaking everyday conversations can be with the people you love, how isolating it can be to try and fail to be understood.

Talking is such a hazard! And yet I love the fact that we, dumb sweet animals that we are, will do it over and over. I chose to draw the conversations rather than write about them because I knew they would be hard not to read. I wanted to make something about racism, sexism, homophobia, and colorism that was impossible to look away from. And if I can make you laugh while you’re squirming? Even better.

I wanted to talk about this very unglamorous, hard-to-define thing, which was how beautiful and hilarious and terrible and heartbreaking everyday conversations can be with the people you love.

You write about conversations you had with your conservative in-laws during the Trump administration — and while you’re very respectful in the retelling, I imagine it was tough to write about. How did you get the courage to share those stories?

Again with the easy questions! Truthfully, I didn’t get the courage. I never felt brave about sharing the exact nature of how my family fell apart, and if I would have waited to feel brave, I would have never put out Good Talk. What I felt instead was a deep, baffled ache. A wonder at how people who loved me could tolerate a country that vilifies people who look like me. A wonder about the stories white Americans tell themselves, the ways they will (literally) ban viewpoints that make them uncomfortable, and meanwhile, here I was questioning my right to say the hard, true thing aloud.

What a country we live in, where we tell ourselves that both of those things hold equal weight — that I should be quiet about the violence my family incites toward me because if I’m not, they will feel funny and then they are the ones who are suffering. Um, no. No, that’s not true, and if it is, then it is really saying something. If knowing who you are and what you’ve done is that awful for you, it might be time for you to change.

There are a few times in the book where you share moments when you were blind to your own privilege. What was the emotion you felt when you realized your blindness, and how did you reckon with that emotion enough to share the story years later?

Writing about a few of those points in the book was excruciating — who wants to look like a jerk? — but also extremely necessary. The emotion I felt then — the one I still feel when I realize I’ve overlooked someone else’s humanity — is shame. It’s always shame, and then where it goes from there is something I’ve had to work on a lot because there’s a pretty rapid domino effect if I don’t stop it. Shame makes me feel defensive, which leads to excuses or anger, none of which are helpful for the people being most hurt by my blind spots. What I’ve been working on instead is my ability to tolerate shame and let it morph into something else — ideally growth, but even if it’s just the ability to hold on to my own feelings and listen carefully, I will take that!

You once mentioned that your parents’ superpower — and perhaps the immigrant superpower — is curiosity. In your experience, is there a link between curiosity and courage?

Curiosity is hands down the biggest gift my parents passed on to me. Because there was so much about this country they didn’t know, they moved through it with a startling amount of wonder and grace and with a lot of grace for other people. When things went south — and they did a few times while I was growing up — my parents got curious. They learned new skills, or read everything they could get their hands on, or asked questions instead of assuming they were right. And while some of that is painful for immigrants — this constant need to assess and reassess — it also gives them real dexterity and nimbleness. I don’t know if I see it as courage as much as I do an essential survival skill. When things get shitty in my own life, I try to get as curious as possible. It has been a healing place for me, the not knowing, the decision to discover everything I can.

Curiosity is hands down the biggest gift my parents passed on to me.