Ten years ago, Brené started the Daring Interview series on her blog. It quickly became one of our favorite features. Now, we are relaunching the series and adding in a few new questions, including some from the late James Lipton, host of Inside the Actors Studio, and Smith Magazine’s Six-Word Memoir.

Many years ago, when I made the decision to go to law school and eventually practice law, there were several legal luminaries who helped inspire the kind of attorney that I one day hoped to be. A couple of them were fictional characters, like Atticus Finch. A few were titans of history, like Mahatma Gandhi. But the one living attorney whose work stood out to me as an example of practicing law with compassion and using your legal skills tirelessly to help the voiceless was Bryan Stevenson.

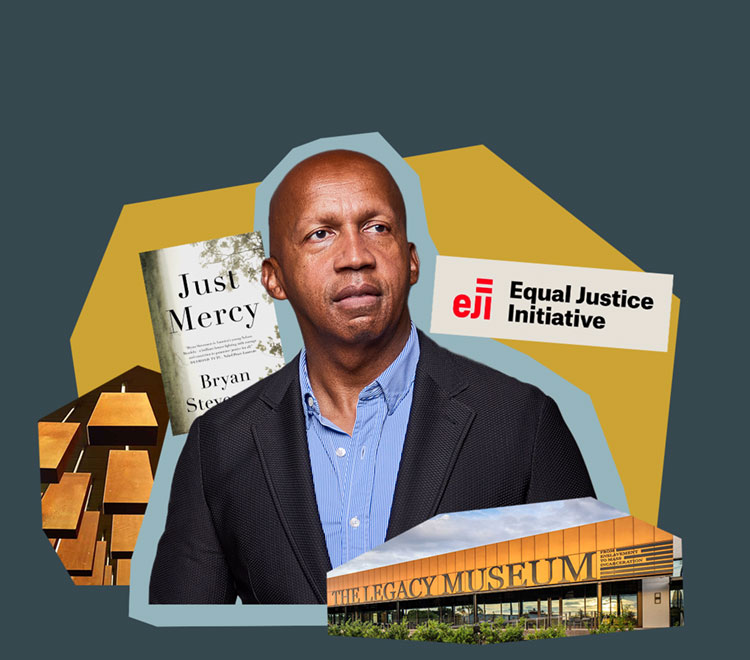

Bryan is the founder and executive director of the Equal Justice Initiative, a human rights organization based in Montgomery, Alabama.

In 2014, he published the memoir Just Mercy, about his early days as an attorney and his efforts to overturn the wrongful conviction of Walter McMillian. The book, which would go on to top the New York Times Best Sellers list and find its way to a big-screen adaptation, stands as one of the foremost examples of compassion; specifically, it is a stark illustration of the way compassion is rooted in the recognition of our shared humanity.

In addition, Bryan has led the creation of two highly acclaimed cultural sites — the Legacy Museum: From Enslavement to Mass Incarceration and the National Memorial for Peace and Justice — that chronicle the legacy of slavery, lynching, and racial segregation and the connection to mass incarceration and contemporary issues of racial bias.

Vulnerability is . . .

Being honest about things that expose your fears, doubts, challenges, and the mistakes you’ve made. Vulnerability means also identifying the ways in which you can be diminished or disfavored because of societal biases and norms.

I started my education in a colored school in the 1960s because Black children were not allowed to attend our local public school.

Lawyers came into our community and enforced the Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education, which prohibited racial segregation in education, and everything changed for me. I admired the power those lawyers had to protect marginalized people, and it motivated me to go to law school. When I arrived at Harvard Law School in 1981, I had never actually met a lawyer. At Harvard, everyone in my orientation group was the son, daughter, grandson, or granddaughter of a lawyer, and they talked about how the lawyers in their family inspired their interest in law. I worried that admitting that I didn’t know a lawyer would diminish me, and so I said nothing about my background.

I later realized that I was starting my legal career by not being honest. I had to track down all the students in my orientation group and explain that I didn’t know any lawyers personally but my life had been changed by civil rights lawyers who helped the poor and people of color. I told them about my great-grandfather, who was enslaved before the Civil War but learned to read despite the fact that he could have been sold or killed for violating anti-literacy laws that banned enslaved people from learning to read. I told them that my grandmother worked as a domestic her whole life but was incredibly literate and insisted that we all be readers — and that this legacy of learning got me to law school.

After being honest about my history, I felt empowered by the knowledge that my journey to law school was different but not inferior, less valid, or less important.

What role does vulnerability play in your work?

Knowing that I can be wrong, make mistakes, or miss things is important to maintaining humility about what I do. I work with a lot of people who suffer terrible injustice. People who have been wrongly convicted of crimes, people facing extreme punishment, people coping with violence and abuse, people who are impoverished and struggling with food insecurity or basic deprivations. The people I serve make me appreciate that I can’t overestimate my capacity to solve problems, which is humbling.

What’s something that gets in the way of your creativity, and how do you move through it?

I often have to get past the discomfort of doing something new and different. I’d been practicing law for many years and was comfortable with litigation, writing briefs, advocacy in courts, and public speaking as well. However, when we decided to create a museum and memorial, this was new terrain.

It was challenging to take these projects on and trust our instincts and insist on our vision when we were putting it together, but I think it paid off in the end. So much of our work is work that hasn’t necessarily been done in the way we’re doing it. I try to not let the absence of precedent keep us from doing something important.

It’s often difficult to share ourselves and our work with the world, given the reflexive criticism and mean-spiritedness that we see in our culture — especially online. What strategies do you use to show up, let yourself be seen, share your work with the world, and deal with criticism?

There will always be people who are critical or unfairly harsh and unkind, but when I think about how often I’ve been inspired by the work and creativity of others, I know there are a lot of people who appreciate what we do and very much look forward to learning about and experiencing our work and the efforts we make. As an advocate, I also have the great joy of focusing on the needs of the clients and people we’re trying to help, and that creates a certain kind of zone of focus that can insulate you from people who doubt, criticize, and condemn what you do.

Describe a snapshot of a joyful moment in your life.

Walking out of a state prison with a client who had been wrongly condemned and scheduled for execution for a crime he didn’t commit. Even though it took nearly 16 years to secure his freedom, walking out with him after he was exonerated — where he could be embraced by his family and reclaim his life — was precious and priceless.

Do you have a mantra, manifesto, or favorite quote for living and loving with your whole heart?

“Do justice, love mercy, walk humbly.”

What is your favorite word?

Compassion.

What is your least-favorite word?

Revenge.

What sound or noise do you love?

Laughter.

What sound or noise do you hate?

Rubbing Styrofoam.

What is your favorite curse word?

Blasted . . . I know, I don’t curse often.

A song/band/type of music you’d risk wreck and injury to turn off when it comes on?

Not a fan of the mood music where single notes are sustained for several minutes.

Favorite show?

The Wire.

Favorite movie?

That I’ve seen recently — Nine Days.

What are you grateful for today?

Ten beautiful nephews and nieces that I adore.

If you could have anything put on a T-shirt, what would it be?

“Each of us is more than the worst thing we’ve ever done.”

Favorite meal?

Hot and sour soup, followed by chicken and vegetables in a spicy black bean sauce with white rice.

A talent you wish you had?

Artistic painting.

Favorite song/band?

Love’s in Need of Love Today, by Stevie Wonder.

What’s on your nightstand?

Barracoon: The Story of the Last “Black Cargo,” by Zora Neale Hurston.

I try to not let the absence of precedent keep us from doing something important.