If there is a person who integrates all the different parts of themselves better and with more celebration than Malaka Gharib, I’m not sure who that person is. A journalist, cartoonist, and award-winning graphic novelist whose writing has been featured in the Los Angeles Times and the New Yorker, Malaka’s work is always about self-determination and cultivating belonging, most often through creativity and community. Here, the new mother shares not just her world view, but the world she hopes to create for her young son.

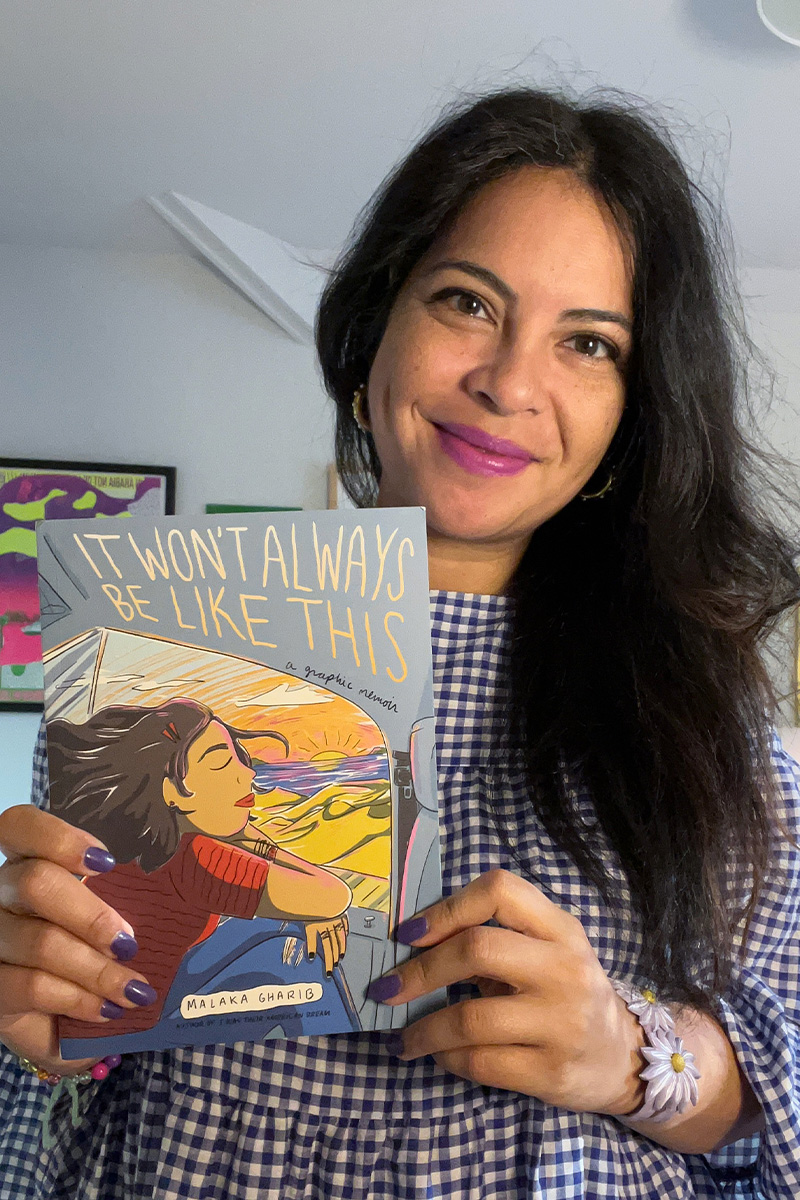

Malaka on publishing day with her book It Won’t Always Be Like This, in September 2022; photography courtesy of Malaka Gharib.

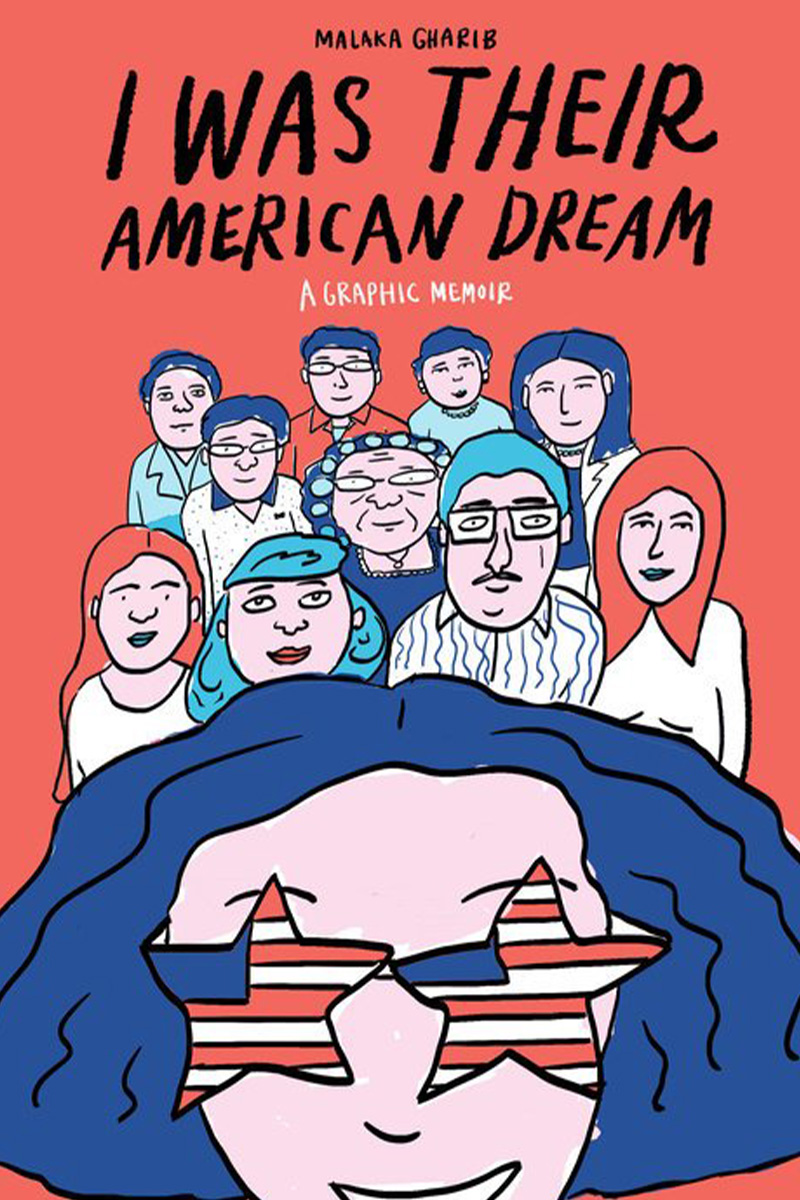

Malaka Gharib’s graphic memoir I Was Their American Dream tells the story of her experience as a first-generation American of Filipino and Egyptian descent; photography courtesy of Malaka Gharib.

Your dad is Egyptian, your mom is Filipino, and you grew up in California. Your books are, in essence, about how you navigated belonging as a child. How do you find yourself navigating belonging as an adult?

As an adult, I know now that there are many ways to belong. I’m a writer, a cartoonist, a Filipino-Egyptian-American, a journalist, and so I like to surround myself with people who are part of those communities to support and inspire me.

When I moved to Nashville in 2020, for example, I found The Porch, a writers’ collective, and got involved. Then I started going to potlucks with other Filipinos. I got coffee with local journalists. I doodled with new comics friends.

And what I learned about belonging as an adult is that it takes effort. You have to be proactive and put yourself out there. Don’t wait for people to come to you — go out and find them. Introduce yourself. And build the strong network you need to give yourself a sense of rootedness.

I’ve always known you to make comics and zines, even before your books were published, and I know you’ve been doing them since you were a child! What is it about comics that helps you express yourself so fully?

I think of comics like little puzzles. There are four parts: the drawing, the dialogue, the narration, and the pace, and they all have to work together in concert to convey a much more complex meaning. Each part has to be doing something different. You can’t say the “sky is blue” in the narration, for example, because you can just draw that. And you can use several panels to convey a sense of time or space, which is a totally different approach to connoting time and space in writing.

And so I like to work within those strict constraints when telling a story. I especially like to tell poignant and profound stories in the fewest comic panels as possible. You can find examples of that on my Instagram.

I think of comics like little puzzles. There are four parts: the drawing, the dialogue, the narration, and the pace, and they all have to work together in concert to convey a much more complex meaning.

I’m intrigued by the title of your book I Was Their American Dream. Did your parents have similar dreams for you? Were they different from each other? How does what you’ve dreamed for yourself differ?

My parents had totally different dreams for me and different dreams from each other. My dad wanted me to be an upstanding Muslim, my mom wanted me to be an upstanding Catholic. They both wanted me to have a job that would make me lots of money, like being a doctor, and have lots of kids. They both wanted me to live close to family. My dreams were to become a writer and artist, to feel comfortable in my skin, to be liked (after so many years of rejection in elementary and high school), and to be emotionally close to my family.

You make art for you, yes, but you also make it to show other people in the hopes that they relate to how you feel, so you don’t feel so alone.

You have a brand new son who, like you, has parents from different cultures! In what way do you think your and your partner’s parenting will differ from the way you were parented?

My parents were great in lots of ways. My mom was fearless and would do things like send me across the world to Egypt by myself (as like, a 12-year-old) to spend the summer with my dad. And she exposed me to the arts — rock music, contemporary art, architecture, and film.

My dad, on the other hand, actually talked to me and told me stories, asked my opinion on things like politics and world affairs (which was fun as a teen). I hope to parent Gus similarly. I want Gus to be independent, exposed, curious, and engaged. But as Gus grows up, I want to be home for him more.

My mom worked two jobs and so I rarely saw her, and my dad often worked during my trips to visit him in Egypt. My mom used to say, “I’m not the kind of mom who will bake you brownies.” Well, that’s the kind of mom I aspire to be.

Malaka writing a letter to her son Gus, a newborn at the time, in 2023; photography by Darren Vandergriff.

“Me tabling at a Nashville zine fest in 2021”; photography by Darren Vandergriff.

As an artist and a creative, what is the biggest lesson around connection that you’ve learned?

You make art for you, yes, but you also make it to show other people in the hopes that they relate to how you feel, so you don’t feel so alone. And a rewarding part of being an artist is sharing your work and your talents with others. Just in the last few months, I’ve shown some work with other Filipino artists at a coffeeshop/gallery here in Nashville, hosted a graphic memoir-writing workshop with a local writing organization, and hosted a Filipino brunch with my Filipino community. For an artist, this is the stuff of life. Being part of something. Sharing. Connecting.