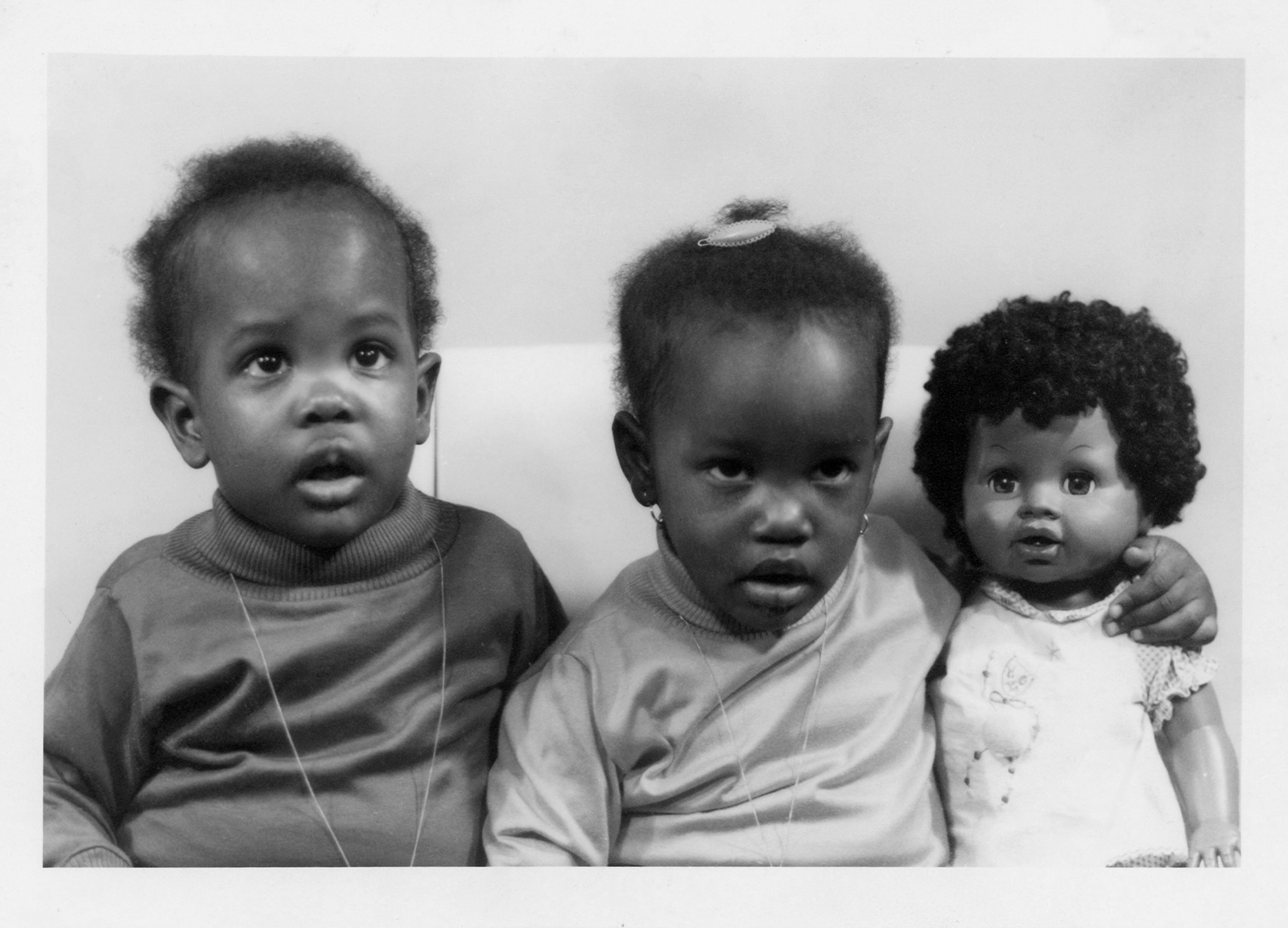

Rich Benjamin grew up knowing almost nothing about his family’s history, including that his grandfather, Daniel Fignolé, was once the president of Haiti for 19 days before being overthrown by a coup and exiled with his family to the United States. Through many years of research, Rich uncovered the events that shaped his grandfather, his mother, and himself, as well as the nations that shaped them in return.

As a cultural researcher and critic, Rich Benjamin tells a story in Talk to Me that is intimate, harrowing, and complex, showing the freedom and power in restoring personal and political memory and illustrating that sometimes knowing someone’s story is the best path to forgiveness and healing.

Talk to Me demonstrates how every story is comprised of so many different stories and perspectives. What was the most challenging part of piecing together family context, Haitian and U.S. news articles, government correspondence, and interviews to tell the story that did justice to all of the people who lived it?

The most challenging part of piecing together this story were the silences that kept confronting me. Most of my family members did not know the story when I asked about it. Those who did know the story, namely, my mother, did not want to discuss the past. Galled by my mother’s silence, I resolved to get to the bottom of it all. So, I ventured to the National Archives, just outside of Washington, D.C. I arrived with modest expectations as to what I might find. Rummaging through the Archives’ cavernous basement over the course of two weeks, I hit a goldmine: more than three hundred pages of memos tracking my grandfather’s activities. Dating from 1946 to 1957, these “classified” memos were composed by top-level American diplomats in Port-au-Prince and directed to the U.S. State Department in Foggy Bottom. And so, a silence on top of my mother’s has shadowed this story, a quietude more public, more sinister. All these silences, enmeshed with one another, presented the biggest challenge to telling a complete story truthful to all its characters.

In my heart and in my head, uplifting remembrance — by way of writing — afforded me so much freedom.

How did you navigate balancing your own feelings and perceptions you had about the people in your family with the uncovered facts that shaped who they are?

As a writer, I try to banish any feelings about the people whom I write about — and focus on the writing. My training as a social scientist guides me in that discipline. I do deep research, seek reams of relevant information, and don’t indulge my “feelings.” This applies to all of my writing. That said, Talk to Me is such a deeply personal book, which looks into my perceptions and feelings about my grandfather and my mother. Sometimes facts bolstered perceptions I had about my mother. Other times, the sheer facts — personal letters, news reports, corroborated interviews — upended the beliefs I was holding about my mother. And those revelations shook me. They are incredible.

A major theme in your book is that world and national history, for you specifically the histories of Haiti, Guinea, and the United States, are family histories. What do you hope people take away about the role of storytelling in history from your book?

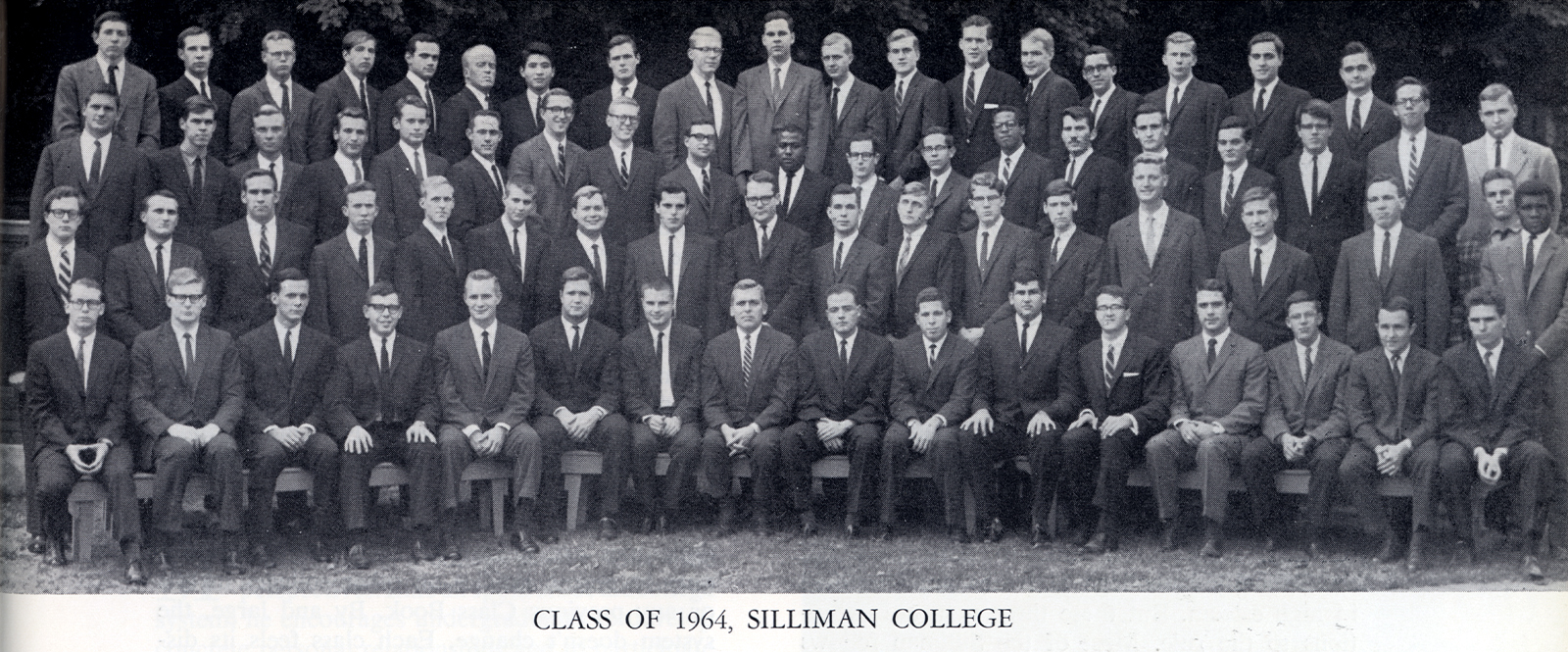

I see history as a big public story. And so, excavating the silenced and untold stories should be at the center of teaching history. This fourteen-year journey to write this book reveals how three generations of educators — grandfather, mother, me — taught things, oblivious to how history was forging us. History — in a biting, quiet, ironic, roundabout way — taught three generations of educators about its sheer power to shape lives. I hope readers learn, therefore, to pay attention — not to sleepwalk through history.

Photography courtesy of Yale University yearbook, 1964.

How has your view of home and belonging changed over the course of researching and writing about your family’s history?

I began researching this book not questioning home, not caring about my roots. And society helped perpetrate that mindset. As a gay man living in a hard-driving, work-obsessed, anonymous metropolis, I am often treated as though I don’t have a family, as though I sprung from a crack in the asphalt — poof! — like an immaculate conception. I remember when my father, once, was taken to the emergency room and then hospitalized in a crisis. My mother phoned my siblings and me. “Please call your father and his nurses,” she frantically clucked. “So they know he has a family!” I chuckled to myself, because her request, so seemingly silly and superfluous, still made perfect sense. Disclosing that my father had family members would not medically cure him; but it would humanize him in his predicament, including to his nurses. Families — and the knowledge thereof — do, in fact, matter. Writing this story showed me how much home, belonging, and family matter — especially when someone is in crisis.

I see history as a big public story. And so, excavating the silenced and untold stories should be at the center of teaching history.

You write: “Writing is a restitution of remembrance to its rightful place. An act of freedom.” Can you say more about the connection between memory and freedom?

For most of my life, secrets held too much power over my family and over myself. And so I dove deep into a fourteen-year discovery to uncover the secrets. In Talk to Me, I tell them all. I had to learn all the things that went unsaid, I had to write them down. I put remembrance in its rightful place with its rightful magnitude — no less, no more. In my heart and in my head, uplifting remembrance — by way of writing — afforded me so much freedom.