Dr. Emily Nagoski is a sex educator and author committed to debunking the myths of what it takes to improve sexual pleasure, connection, and relationships, with a lot of science, humor, and movie references.

You might know Dr. Emily Nagoski from one of the most popular Unlocking Us episodes On Burnout and How to Complete the Stress Cycle, where she and her sister, Dr. Amelia Nagoski, discuss the causes and impact of burnout and how to move through emotional stress and exhaustion. Or, you might know Emily from her New York Times bestselling book Come As You Are, which demystifies the science of female sexuality, or from her popular podcast by the same name.

Her latest book, Come Together, takes on science that makes for strong, long-term sexual connection.

Emily on stage in Brookline, Massachusetts, during the Come Together book tour; photography by Robyn Manning-Samuels.

Pictured with Emily’s profile article in the New York Times, her book Come Together was also a New York Times bestseller; photography courtesy of Emily Nagoski.

Why is prioritizing pleasure and connection so important in both our sexual lives and our lives as a whole?

Connection and pleasure are different things, and what they contribute is different. Connection is required for day-to-day survival. Life is too hard to get through it alone, and humans are not built to get through it alone. And the couples who sustain a strong sexual connection turn toward each other with admiration and trust.

There is something that quality connection and pleasure share: safety. Our brains only have access to the experience of pleasure when we feel safe enough, and quality connection is one aspect of what helps our brains feel safe enough.

When you realize how hard the world makes it to feel safe enough and easeful enough for your brain even to have access to the possibility of pleasure, you’ll find that constructing a life that prioritizes pleasure, centers ease and joy, is in fact an act of revolt against systems of oppression that thrive when we feel afraid, helpless, joyless, and exhausted. It’s the actual revolution. From this viewpoint, the extent to which we all have access to pleasure, ease, and joy is a measure of justice, because it means we all have both enough support in life and social permission to enjoy our lives.

Refuse exhaustion. Center pleasure.

Everything you were taught about how sex is supposed to work in long-term relationships is wrong. All of it.

So much of Come Together discusses topics of emotional literacy and understanding our own and our partner’s emotional experiences. Has your view of the importance of our emotional experiences changed over the course of your career as a sex educator?

I want to give a more complex answer, but the actual answer is just no.

In my first book, Come As You Are, there’s a chapter on stress and feelings that my (excellent, brilliant, wonderful!) editor suggested I cut because it “wasn’t about sex.” I had to keep it because sex happens in an emotional context, and that emotional context influences sex in our brains. I knew it was important because even then, back in 2013, I had been teaching it for ten years in the classroom.

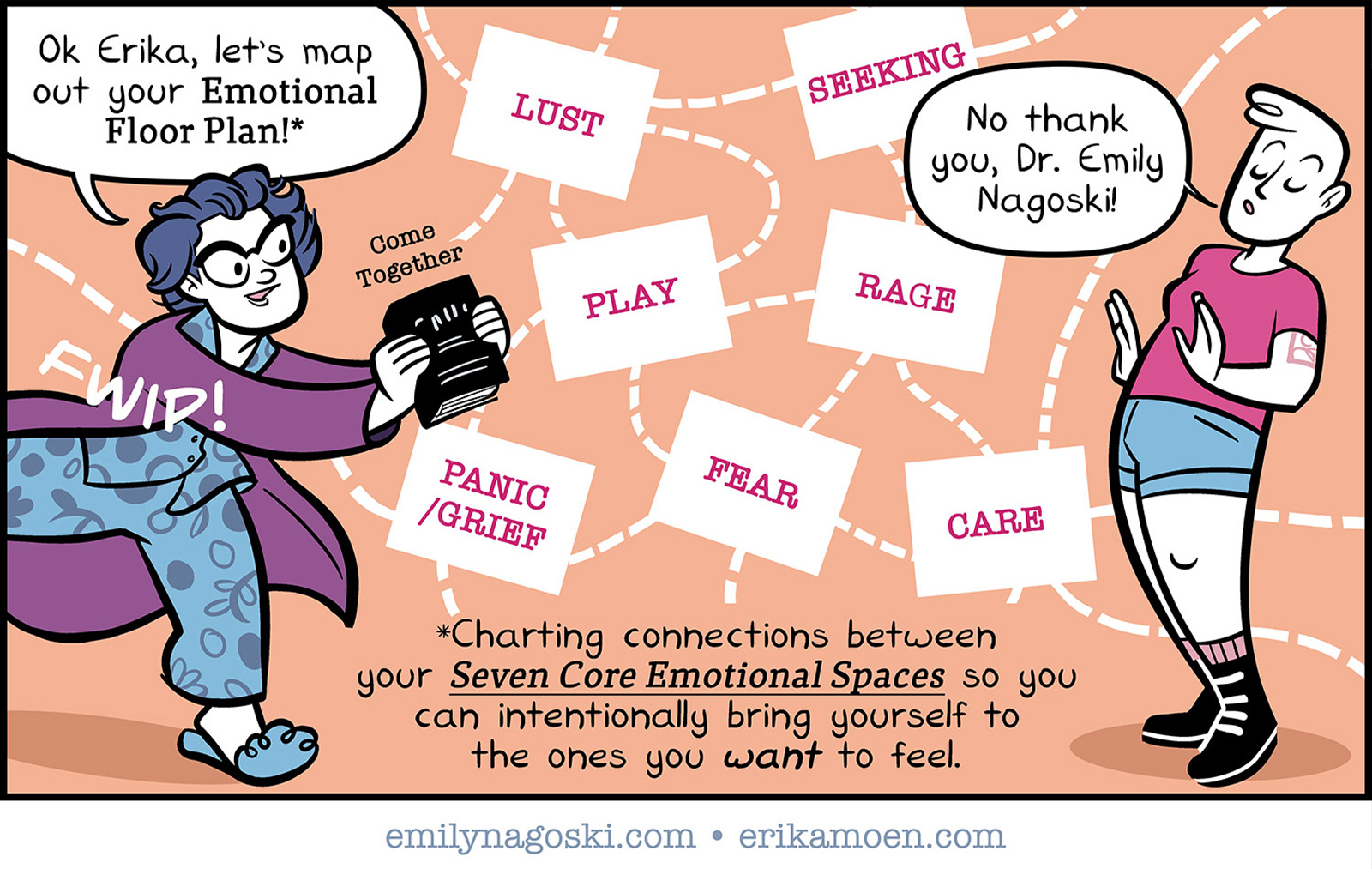

What has changed is people’s recognition of context’s role in our access to pleasure! My editor on Come Together never questioned two big and complex chapters on the primary process emotions, because it was clear to her how necessary it is to understand the whole thing in order to understand the part of it that is directly related to sex.

You propose approaching ourselves, partners, and external factors in life with a “calm, warm curiosity.” How do we tap into this approach when we feel far from calm or curious?

To begin with, don’t try to have a conversation with your partner about sex (or anything highly sensitive!) when you “feel far from calm or curious.” All the emotion and relationship research over the last 50 years has clearly established that when we’re stressed out, our ability to listen flies out of the window.

If one or both of you finds you truly can’t access calm curiosity when the subject of sex arises, talk to a sex therapist together. But there are lots of strategies for opening a conversation about sex in a way that helps establish a tone of warmth and kindness. For example, start with the good stuff. Talk about a shared memory of some great experiences you’ve shared, if there are any.

The goal of a conversation like this is to invite greater closeness, and people are worried that it could have the opposite effect. If you’re struggling to discuss sex from a warm and curious frame of mind, maybe one or both of these fears are getting in the way. In that case, name those fears and see if you can, as a team, create strategies for what you could do in case something like that happens.

Meet Nagoggles, the Sex Ed Puppet; photography by Richard Stevens.

Emily speaking at Vagina Museum in London; photography by Robyn Manning-Samuels.

In your book, you share stories and examples from your personal life as well as declining to share certain stories from your life. How do you discern the line between what is vulnerable and courageous to share versus what is intimate and not for sharing with a wider audience?

My choices about disclosure have rarely been about whether or not a detail is “too intimate” to share. The rubric is: is this helpful for the student? The answer is nearly always no.

A major element of training for any sex educator or sex therapist is exploring whether and when to self-disclose. My default baseline is “no self-disclosure,” so that I’m as blank a slate as I can be for my students. It’s important that they not project other people’s opinions onto me, so that they feel comfortable talking to me about absolutely anything, knowing that I will never judge or shame them.

The next baseline, when I’m considering if a certain story belongs in my work, is my spouse’s opinion. If it’s a story that involves him, he has 100% veto power.

A common assumption people make is that sex educators have wildly adventurous, highly orgasmic, and very frequent sex. The reality is we struggle too — though we have the benefit of being great at talking about it with our partners and have worked through much of the shame and judgment that our cultures taught us. I realized it could be helpful for people if I dispelled that myth and talked about the tools I used to help myself.

From this viewpoint, the extent to which we all have access to pleasure, ease, and joy is a measure of justice, because it means we all have both enough support in life and social permission to enjoy our lives.

What myth about sex and creating lasting sexual connections do you most want to dispel?

The easiest way to answer this question is just: Everything you were taught about how sex is supposed to work in long-term relationships is wrong. All of it.

First, people kinda think that if you “have to” talk about sex, there must be a problem. The reality is that couples who sustain a strong sexual connection talk about sex all the time. They talk about it the way they talk about all their shared pleasurable hobbies, like their sports team or favorite musicians. You don’t just talk about it while you watch the game or the performance, you plan for the game or the show, you talk about your favorite memories, you discuss your hopes for the future, you sing together, you play together.

Second, couples who sustain a strong sexual connection over the long term don’t always plan or schedule their sex . . . but they often do. People think great sex is just going to happen, you know, the way you just “naturally” and “spontaneously” throw a whole dinner party for ten.

Above all, couples who sustain a strong sexual connection recognize that they’ve been following somebody else’s rules. They decide to set aside other people’s opinions and really get to know what’s true for them, what’s true for their partners, and what’s true for this sexual connection in this season of their lives.