Why the ABK Team loves this book:

It’s easy to say a music video is just a music video, or a TV show is just a TV show, not to be taken seriously or deeply analyzed when it’s viewed in isolation. However, pop culture does not exist in a vacuum but rather in an ecosystem of messaging that tells us what is valued, expected, and rewarded in society.

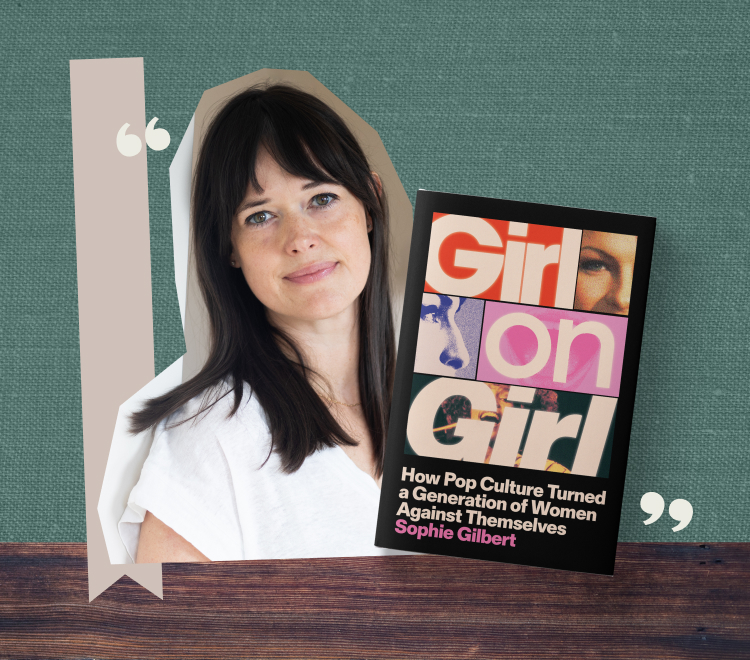

Taking both a birds-eye view and a microscope to many of the cultural moments we lived through, movies we watched, songs we listened to, and other elements of pop culture from the 1990s to the 2010s, Sophie Gilbert makes the case that pop culture is a powerful force that shapes our view and treatment of women in public and in private in her new book, Girl on Girl: How Pop Culture Turned a Generation of Women Against Themselves.

“Our culture teaches us everything,” she writes.

Our three favorite quotes from the book:

“Popular culture isn’t an innocuous force; we don’t go through adolescence—watching scenes and reading books and hearing jokes and listening to all kinds of dialogue—while wearing an invisible force field that bounces bad ideas away. We learn an awful lot of what we know from the stories we encounter.”

“Analyzing history together is, above all, an expression of hope: We try to understand all the ways in which things went wrong so that we can conceive of a more powerful way forward.”

“It’s been well-documented by now that this particular decade was crushing for many of the women who lived through its lens, and they deserve reappraisal. But I’m interested, too, in what this moment did to those of us who were simply spectators: curious and even envious of the stars whose degradation was offered up to us as thrilling, perpetual, stakes-free entertainment. How did it condition us to see ourselves? And, maybe more crucially, what did it condition us to think about other women and what they might be capable of?”

Three questions for the author:

As someone who lived through the events and culture you excavate in Girl on Girl, what would you go back and tell your sixteen-year-old self in 1999 from the lens you have now on the pop culture that shaped your generation?

So much of the culture of that moment was thrilling to me at 16, but a lot of it, even then, felt unsettling. I would love to say that it’s okay to feel uncomfortable, and that actually discomfort is a sign of strength, not weakness — it signals that you know more than you think. I remember so well feeling like I had to suppress my own instincts to be accepted, but my instincts were actually pretty good even then.

On understanding how tabloid culture portrayed women in the early 2000s, you write “disgust is one of the most powerful human responses and one of the least studied.” Did you learn anything in your research about how we can counter the use of disgust in the media that turns people against marginalized groups?

Simply being aware of when disgust is being weaponized is really powerful, I think, as is learning to identify how it’s being triggered and to what end. And it’s crucial to not ever let politicians or public figures who use disgust-engendering language seem like the new normal, because what they’re doing is both extreme and dangerous.

What is a recent piece of pop culture that excited you about how women are portrayed?

There have been a few! I loved Dying for Sex on FX — how fearless Michelle Williams’s performance was, and how willing the show was to really get into the complexity of desire. I appreciated how willing Babygirl was to be ambiguous and to leave space for us to interpret it. I also adored the last Bridget Jones movie — the pathos and humor of Bridget’s journey in midlife, her charm, and her resilience.