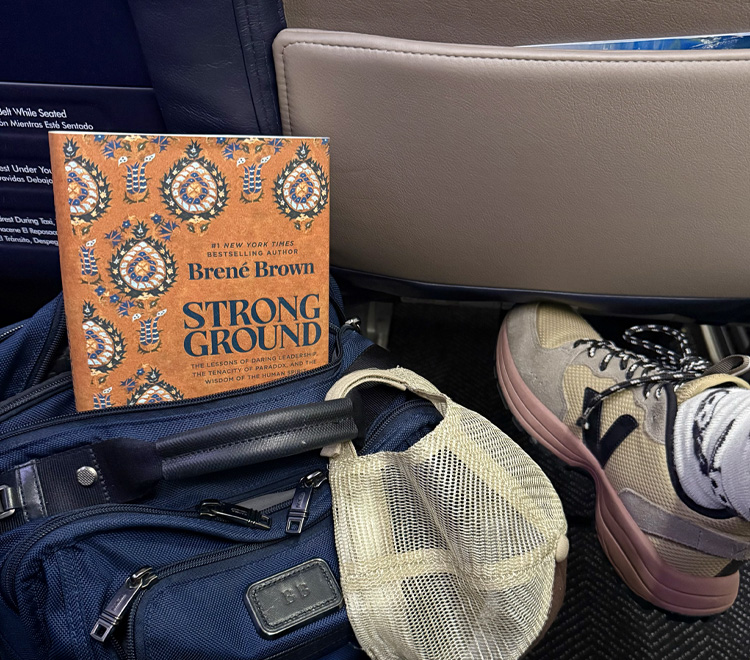

When the first box of a new book arrives, I always give the top copy to my mom and I keep the second one as my “travel copy.” Strong Ground is my first book without her and holding that top copy in my hand was a tough moment.

After giving it some thought, I’ve decided to share the “top of the box” copy with her. I’ll carry it with me and she can just ride around in the pages. I’m pretty sure she’ll hang out mostly in Chapter 4 which is titled, Paradox and the Human Spirit.

My mom was all about the paradox way before most of us realized the power it wields. Today, the ability to navigate paradox is key to courageous leadership and this chapter introduces readers to some of my favorite teachers — some spiritual and some straight from the leadership world (Hello James March and Jim Collins).

Here’s an excerpt adapted from Chapter 4 in Strong Ground: Lessons from Daring Leadership, The Tenacity of Paradox, and The Wisdom of the Human Spirit (2025):

When I told my editor that I wanted to use the phrase “the tenacity of paradox” in the subtitle, he half-jokingly said, “I’m guessing this relates to the fact that you never, ever, and I mean NEVER, stop writing about paradox. Book after book.”

I flashed my slyest smart-ass smile and said, “Yes. And no.”

He tried negotiating by suggesting “the power of paradox” but I insisted on tenacity for the simple reason that paradoxes are unflinching and stubborn. We can run from them when they confuse us or try to quit them when they frustrate us, but, like me and my subtitle, they never surrender.

In its original Greek, paradox is made up of two words, para (contrary to) and dokein (opinion). The Latin paradoxum means “seemingly absurd but really true.” In my experience, paradoxes are incredibly tenacious. Humans get so uncomfortable straddling the tension and uncertainty that surfaces when two seemingly opposing ideas are both valid, that we often simply give up. We let go of the tension and pick one idea, normally the one most familiar, and make ourselves feel better by discounting or diminishing the competing idea and/or the idea holder.

The gift of the paradox is that if we hang in there and tolerate the tension — grounding down and holding both ideas — a new and deeper level of understanding is born. Paradox is stubborn and never lets go. We are the ones who tap out.

For example, in my work life, I’ve spent five years trying to run from the paradox of freedom and commitment. The idea of having my life reduced to 30-minute scheduling blocks sends me straight into one of my least favorite emotions — despair. For me, despair is that soul-crushing feeling of having no agency, no power to change anything. I once heard Rob Bell define despair as, “tomorrow will be just like today.” This is the heaviness I feel when I lose ownership of my time.

What I craved and still crave more than anything is time, freedom, and flexibility. I want a life that makes me periodically unfindable. I’m sure this is why swimming laps is my love language. When you’re under the water, you’re totally unavailable. I also need time to read, to write, to create, and to think.

For years, I protected my “freedom” by refusing to plan and schedule. I waited until the absolute last minute to make up my mind about my day, and I overcommitted on a regular basis because, when I checked, nothing was blocked out on my calendar. The result? Chaos, panic, anxiety, and absolutely zero freedom.

Then, one day, after I was completely worn down and convinced that I would never outsmart the paradox of freedom and commitment, I scheduled my next haircut before I left the salon. The woman who worked at the desk was shocked. I’m sure she was thinking, Does this mean she’s not going to call crying in six weeks because she’s desperate to get in before a big trip? One scheduled appointment led to the next and within a few weeks, I was calendaring meetings and blocking time for creating in equal measure. Making and keeping commitments and writing them down miraculously led to more freedom. And collective relief from a team that I had subjected to a lot of unnecessary stress and legitimate frustration.

In the Introduction, I shared several tough, personal paradoxes. I want to compete on the court with intensity, which ultimately means committing to consistency in the gym. I want more speed and agility, which means developing and maintaining a strong relationship with the ground. I guess you could say that I’m also committed to NOT being the youngest person in my maternal line to end up in assisted living, so I’ll need to accept being the oldest person at the gym on many days.

Carl Jung was my gateway drug into paradox. I wish I could take back the many times that brooding teenage me rolled my eyes at my mom when I found her buried under a stack of books by Jung. Mercifully, I had many opportunities before she died to thank her for the courage it took to read weird books, go to therapy, and surface the unsaid in our family. I could draw a straight line between her reading Jung and me sitting here writing this book. Her determination to change the trajectory of our lives was the purest form of love.