Brené Brown: Hi, everyone. I’m Brené Brown and this is Unlocking Us. Before we get started with our podcast conversation today, I wanted to give you an update about our summer vacation. I will be taking off from Unlocking Us from June 2nd to June 16th. We will be back with Unlocking Us on June 23rd with a five-part summer series. It’s like a sister summer series. I’m going to be doing a five-parter with Ashley and Barrett on The Gifts of Imperfection. So time to dust off that thing, or if you’ve got the new, the 10th anniversary addition, get that out. We’re going to go through the guideposts together. We’re going to talk about what we’ve learned. I think… Barrett, is it still your favorite book?

Barrett Guillen: Yes.

BB: So we’re going to do a five-part sister series on The Gifts. We’re nervous [chuckle] because we’re like, “Is there going to be a special hand sign for like, we’ve crossed the boundary, or we shouldn’t share that?”

BG: Yes.

[laughter]

BB: Barrett’s saying “Yes, there should be.” So off from June 2nd to June 16th, back on June 23rd with Ashley and Barrett on a five-part The Gifts of Imperfection summer series. I’m taking off from May 31st to July 5th for Dare to Lead a little bit longer of a vacay. And I’m going to be back on July 12th. What the hell? I may be back on July 12th with a two-part solo series called “The hardest feedback I’ve ever received.”

[laughter]

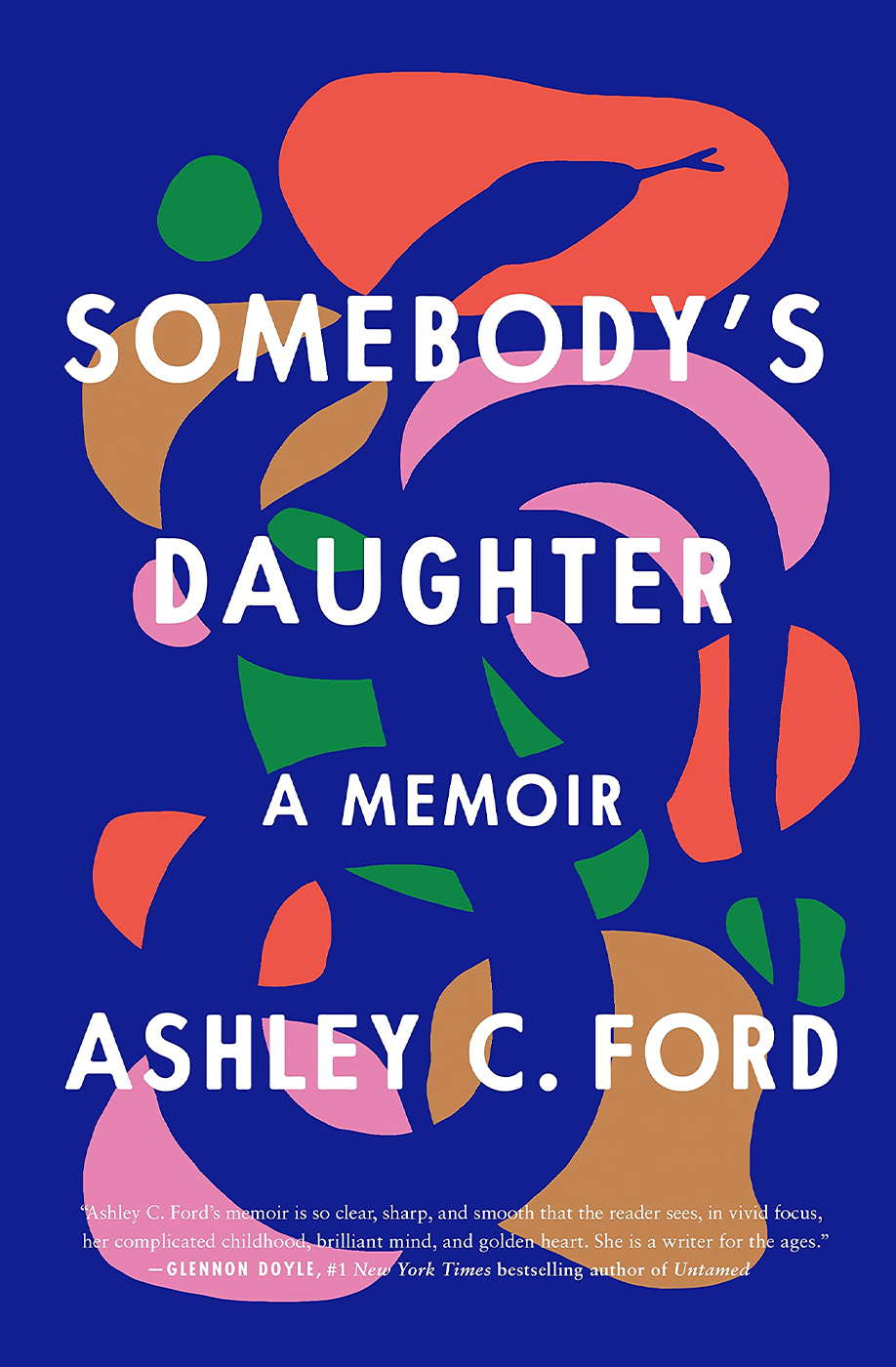

BB: As Barrett laughs, I thought I’d shared that with you, because we always talk about how to give feedback and we need to receive it. But then, how do we not hot potato it when we get it, which I can do sometimes. These short summer breaks are going to be followed by an incredible remainder of 2021. Lots of great conversations, interesting guests, some solo episodes. So grateful that you’re here. Let’s get on to… Oh my God, this conversation. I am talking to Ashley C. Ford, one of… I don’t know, just whatever you say… You know when there’s that person that you know and whenever you say her name to someone else, they go, “Oh my gosh, she’s my favorite person.” She’s just one of my favorite people. So Ashley has written a memoir called Somebody’s Daughter. It’s coming out, the launch date is June 1st. And we talk about hard things. We talk about what it really means to own our story and what it means to write it and share it and how writing it and sharing it is a part of healing. And whether you’re a memoirist, or a writer, or you keep a journal, this is, I think, one of the most important conversations I’ve had about what it means to really grab the pen, walk into the story, own it and write a new ending.

BB: Ooh, Ashley C. Ford. It’s a hell of a conversation. Before we get started with our conversation, let me tell you a little bit more about Ashley. Ashley C. Ford is a writer, a host, and educator who lives in Indianapolis, Indiana with her husband, poet and fiction writer, Kelly Stacy and their chocolate lab, Astro Renegade Ford-Stacy, hyphenated name, in case you’re going to do any formal invites for Astro Renegade. Her memoir, Somebody’s Daughter is published by Flatiron Books. It’ll be out June 1st. Ford is the former host of “The Chronicles of Now” podcast. She is co-host of the HBO companion podcast, “Lovecraft Country Radio,” seasons one and three of Mastercard’s “Fortune Favors the Bold,” as well as the video interview series “Profile” by BuzzFeed News and Brooklyn-based news and culture TV show, “112BK.” Man, she’s everywhere. And that’s good, because we need her everywhere. Ashley was also the host of the first season of Audible’s literary interview series, “Authorized.” She has been named among Forbes Magazine’s 30 Under 30 in Media, Brooklyn Magazine’s, Brooklyn 100, Time Out New York’s, New Yorkers of the Year and Variety’s, New Power of New York. All that is true. She is incredible and she’s with us today. Let’s jump in. Hello, Ashley C. Ford.

Ashley C. Ford: Hello Brené Brown.

BB: Oh man, just seeing your face… I get to see her on Zoom, it just makes me happy.

AF: That’s mutual. Vice versa, I’m very happy seeing your face today and mine. Because, to be perfectly honest, you’re not guaranteed the opportunity to see your face everyday, so.

BB: That is true. I say that when I wake up in the morning. Thank you for another shot at this.

AF: Absolutely.

BB: I’ve got to start by saying that Somebody’s Daughter, your new memoir, blew me away.

AF: Yeah. Yeah.

BB: There’s a chance that I’m going to cry, starting now.

AF: Me too. So we’re just going to be crying together, again.

BB: Again.

BB: Laura Mayes heads up the podcast for us and we read everything together. And I get this call at 7-something this morning and she’s like, “Oh God, where are you in the book?” I’m like, “Stop, because I’m almost there. Don’t say anything.” She’s like, “It’s so good. Her writing is so amazing.”

AF: Oh my goodness. Thank you so much. Thank you for saying that. Oh, thank you for reading it. There’s so much of who I am in this book that I’m trying to connect, I think, with other people through sharing that and connect in a sense of shedding a certain sense of shame and hoping that doing that for myself encourages other people to do it for themselves. Because it’s better. It’s just… It’s better. And that people are taking the time to read the story of someone who, for a very long time, didn’t think they had a story to tell. That gives me a lot of hope. Not just personally, but for people.

BB: The last time you were on the podcast, we were talking about the Hungry Hearts anthology and I asked you a question where we start the podcast all the time, which is, “Tell me your story.” Your story, it was like reading a movie. It’s a unique experience. The last time I really felt like I was reading a movie was when I probably read Circe by Madeline Miller. Yeah.

AF: Oh, I love that book.

BB: Yeah, that’s how I felt. So I’m not going to ask you about your story, because your story’s in the book and I want to ask you a different question. A question that I would hate probably for anyone to ask me, but I’m going to ask you. Tell me the story of becoming a writer and fully owning that you, Ashley C. Ford, are a writer of great power and eloquence.

BB: Tell me the story of owning becoming a writer.

AF: Wow. I fancy myself a smart person, a smart woman. And I was having a conversation with a therapist in college. And I was talking about the fact that I had written something for a class and my professor really liked it and told me that maybe I should continue working on the story that I had started under her instruction. And this counselor said to me, “Well, what do you think about that?” And I was like, “Oh, you know, I’m not doing that.” First of all, I was like, “Black people don’t do that. Okay? We don’t tell our business. We don’t embarrass our families or our parents by revealing to the world what happened and airing our dirty laundry.” And this counselor said to me, “Our dirty laundry? Is that your dirty laundry? Did you put the dirt on the laundry that you’re worried about sharing?” And I was like, “Well, no. If it was me, I’m okay with talking about what I’ve done because I want people to know, or I feel connected to people by talking about my mistakes sometimes. Where I’ve messed up and where I’ve gotten better.” And the counselor said, “Well, if it’s not your dirty laundry, then why did you have it? If it’s not your dirty laundry, why is it in your basket?”

BB: Oh man.

AF: And I was like, “Huh.” And I had to think about that a lot. And then they asked me the question that really messed me up, which was essentially, he asked me, “Why don’t you deserve a story that’s just your own?” And…

BB: Ruthless.

AF: Yeah, yeah, I needed that [chuckle] at the time. And I couldn’t come up with good reasons. And I try to think of myself as a reasonable person. And the evidence of the way I was able to connect with people through writing was all around me and it started to feel like to deny it, was to choose to believe something that is evidently wrong. Why would Roxane Gay, who was my friend, a writer I admired at the time, even before she became my mentor, who had reached out to me about my writing and about how much she liked it, why would she lie to me? Why would this person reach out to me to say these things if they weren’t true? And I would come up with reasons in my head, like, “Oh, she feels sorry for me.” Or, “Oh, she wants to encourage a young writer.” And I could come up with so many excuses for why I was not who I very clearly was, or that I wasn’t good at doing what I very clearly had some talent for doing. And the evidence would not bear out.

AF: The evidence that that was true, that I was bad, that I shouldn’t do it, that I couldn’t do it, it never showed up. It never showed up. I tried and people heard me, people read me and they liked it. And lying to myself about that wasn’t making any part of my life easier. So at some point, I had to sit back and go, “Okay, if that’s not working, it’s time to try something new.” Because you’re not going to stop writing. Writing is a thing you’re always going to do. You’re not going to stop. So if you’re not going to stop writing, then you need to be willing to be honest with yourself about what happens when you write, how it affects people, how it affects you and the potential for who and how it could affect someone next. And there’s a responsibility in that and I didn’t want to deny that responsibility. I didn’t want to abdicate my responsibility, not to share my story, but if I’m going to share my story and it’s going to connect the way it connects, then it’s my responsibility to own that that is the truth and to walk and work like that is the truth, I guess. Sorry, I ramble a lot, but that’s pretty much it.

BB: I’d call that a lot of things, but not a ramble. It wouldn’t even come up as an option. You touched on something really hard, which I want to ask you about. I have to say that I fell madly and deeply in love with little Ashley in the book.

AF: Me too.

BB: Did you?

AF: Yes. Ooh, okay. Not even there yet, Ashley. I realized in the writing of this book, especially in the starting writing of this book, that in the first drafts of the way I wrote about myself as a child, was not the way I actually felt, it was the way I thought other people saw me. Which was pretty weak, sensitive, troublesome, burdensome, all of those things. I wrote about myself that way. I wrote about my childhood that way because that’s the way the adults around me often made me feel. Not all the time, but often made me feel. And as I really started to think about these stories and look back, I started thinking, “How would I react to a kid now who behaved that way?” I used to be a nanny. Loved it. And those boys… I’ve nannied these two boys, Charlie and Wilson. And those boys would do things that didn’t make sense, that were all over the place, that were big and loud and just wild. And I loved it. I loved it. I loved watching them, I loved being with them, I loved where their minds would go. I loved the little strange and funny things they said. I loved it so much and I started thinking, “Was I very different from these boys as a child?”

AF: I used to say wild things like that. The reason almost why it fills me up with so much joy to hear this kid say something weird is because I know I would have said the exact same thing when I was a kid. So how come adult me can look at this kid and think, “Man, that’s so funny.” Or, “That’s so cute.” And it seems like none of the adults around me were able to do that in my direction. And as I thought about that, I just kept thinking, “Oh, wait. I’m the adult now. [chuckle] I’m the adult now.” And I can sort of love that child part of me, the way she deserved to be loved then, the way she wanted to be loved then. And I can give her that now. Even in the book, as I write these stories, it’s like I want to write them clearly and I want to write them truthfully, but I felt like, at times, I was having conversations with myself as a child off the page. Sort of saying, “I know that this happened and I know that this was the reaction to it, but that was kind of funny. Don’t you think that was kind of funny? Don’t you think it was actually kind of funny for you to say that?” Because I’m actually laughing inside about it. And almost feeling like that part of me opened up back to me.

BB: Wow.

AF: And was kind of like, “Yeah. You want to hear another one?”

BB: Yeah.

AF: I don’t know how else to describe it. It’s like it became a conversation. And I just like… Being able to have that conversation with a child version of me sort of… It made me more relaxed, it made me a little bit funnier, because I was able to tap into the part of myself that was a little performative and loved to be silly and loved to put on a show. Something that has always been true for me, but I’ve always had weird shame around and not knowing why I had that shame, you go back and you listen to your child self and you’re like, “Oh yeah, I remember how that was taken from you. I remember how slowly, over time, the part of you that would jump up and dance and do the scene from the movie in front of people, how that part of you got smaller and smaller and smaller as the people around you dismissed you over and over and over again.”

BB: Or shut it down completely, yeah.

AF: Or shut it down completely. And I’m sorry for that. I know I didn’t do it to you, but I’m sorry that that happened to you and you’re going to be okay. And it’s weird. I always thought that was a bunch of woo-woo bullshit, to be perfectly honest, that we talk to your inner child. I’m like, “What? I’m 34. What inner child?” And it wasn’t bullshit. Having those conversations with myself, I’m like, “Oh, I get to be all of it. All of the best things I was then I can be right now. Wow.”

BB: That’s powerful.

AF: I wish I’d known that the whole time.

BB: I’m digging into these things because I have rarely seen anyone do this as beautifully as you’ve done it, especially going back to childhood and going back around trauma and going back around hard things and hard choices made by people we love. Was there a stark moment or was it a collection of moments where you’re like, “Shit, this little girl that I’ve built on the pages is the projection of me through adult eyes.” Or was it a big aha, or just a collection of ahas?

AF: It was definitely a collection of ahas, especially because of the way I wrote the book, which was very much in pieces and in sections, just the way my brain worked in forming it. And so I’m working really hard on one section and I know I’m going to get back to these other sections, but they’re in still kind of a rough place. And I realized, looking at the sections that I had spent the most time with, that the more time I had spent on those sections, the more compassion I was able to offer everybody in the scene, including myself.

BB: Okay, wait. I want to stop you there. Everybody in the scene. So I have to say, do you think about it that way? Because these vignettes read like a series of movies to me.

AF: Yeah.

BB: Did you think about it that way?

AF: I did absolutely think about it that way. The way I’d battle that part of my brain that would say things to me like, “Black people don’t write memoirs, girl, especially Black girls. And if they do, they don’t write it about their childhood. And if they do write about their childhood, they at least have the decency to wait until their parents are dead.” You know what I mean?

BB: Yeah.

AF: That was the thing in my head for a really long time and I started thinking about whether or not I really believed that. Is that something I believe because I’ve been told that that’s just what we do, or that’s just what people do. Or do I really believe that the kindest person in a room is the person who is least likely to tell the truth about what they’ve dealt with and where they came from? Is that actually true?

BB: Wow! What a question.

AF: And it wasn’t. It wasn’t true.

BB: Wait a minute. Can you ask that question again, for us?

AF: I would say, “Is the kindest person in the room also the person least likely to share about where they came from and who they are? Is that the kindest person? Does that make that person the kindest person in the room?”

BB: No, that person is the most dangerous person in the room.

AF: I agree, I agree. And ultimately, what I came up with, was that I wanted to be fair. I just wanted to be fair to everybody and being fair meant no heroes and no villains. You read the end of the book, some people are going to come out looking better than others in the end, but nobody is purely a hero and nobody is purely villain. People have their own things going on, people are dealing with their own tough, complicated lives and I thought that is the most accurate story I could tell and I wanted it to be really accurate. That’s what’s accurate, because I know people will read this book and that some people will feel very sorry for the child me and they will feel like the childhood I experienced was steeped in tragedy and I don’t look at my childhood that way, I don’t think that would be the truth of my childhood. I think that there was tragedy, I think that there was a lot of shame, too much silence, too many secrets, absolutely. But there was also a lot of fun and there was a lot of laughter and there was a lot of joy and there was a lot of support and all of those things existed at the same time.

BB: God, like life.

AF: And it was so hard… Yes and I wanted to write a book about my life. When I said I wanted to write a book that told a story about my life, I wanted it to tell the story about life, I didn’t want it to tell a story that was just tropes, I didn’t want to tell a story that would just be familiar to the common denominator. I wanted a story that looks like life and my life, because even if my life is not the most interesting, the most tragic, the most hopeful or exciting, my life is so worth telling about, my story is so worth sharing and there are just too many points of identity or experience or circumstance that I didn’t see written about enough. And I don’t want another person who meets me in those points of identity or experience or circumstance to walk into a book store and feel like they can’t find a book that just tells them they’re not alone in that place, that they’re not the only one who dealt with that.

BB: It’s got all the feelings, there’s such a fierceness about the book, there’s in equal parts tenderness, but man, the two words that came to mind as I was reading, generous and unapologetically messy.

AF: Yeah, absolutely, just like my brain.

BB: We have so much research now about how when we look and evaluate trauma, the trauma of secret keeping is often greater than the trauma of the event itself or the series of events, we know that and we know that writing our way… We’re going to talk about Roxane’s piece on “Writing into the Wound” in a minute, but we know that writing is one of the most profoundly powerful ways of healing trauma. And folks that write about their trauma even in limited amounts, you don’t have to write a memoir, but just write about their trauma, maybe just for themselves, the health indicators, the healing indicators, the correlations are so much more positive. But there always comes a sticking point and I’ll tell you what it is and this may be something we’ve already touched on a little bit, but I want you to speak to it explicitly because man, it’s rare that I’ve seen someone do it like you’ve done it, which is, I cannot truthfully share my story because it implicates people I love who have done me great harm.

AF: Yeah, yeah. This is sometimes a hard question for me and it’s going to continue to be a hard question for me for a few different reasons and I’ll say in the case of my mother, this is not a book that my mother would have wanted me to write, but it is not a book she would have stopped me from writing and it might be a book that she never reads.

BB: Yes.

AF: And that is an interesting place to be because I’ve noticed that when people ask me questions about my family on how they might react to the book or how loved ones might react to the book, those are really hard questions to answer, mostly because the dynamics of my family do not usually reflect the normal dynamics of what other people would think of. Everybody comes with their own ideas of what a mom is like, what a dad is like, what aunts and cousins and grandparents are like and how they involve themselves in your life and how you involve yourself in their life and all of that and a lot of those things just do not describe my family dynamic. My mother and I are on good terms.

AF: I love my mama, my mama loves me, but I don’t have and have never had the kind of relationship with my mother where we talk very often on the phone or in many other capacities. So it’s this thing where, okay, I know that she sees things happening about the book, we have talked about the fact the book is coming out, I’ve told her, “If there are things in there that you want to talk about, I’m so open to that we can have those conversations,” but I have to be okay with the fact that my mom might just kind of pretend this book doesn’t exist. She might just pretend it doesn’t exist, which will be hard, but she’s really good at it, let me tell you. And in that case, if that’s what she needs, I don’t need her to read it or like it, or even be proud of it. I don’t have that kind of relationship with my mom where I feel this want for her in this place of my life. And sometimes I feel really bad about that.

BB: Do you? Yeah.

AF: Oh, yeah. Oh, yeah. I feel really bad about that sometimes because I’ve seen what it’s like for other people in both directions.

BB: Yeah.

AF: I’ve seen what it’s like when I couldn’t call my mom, like that thing. And I’ve also seen it where it’s like my mom won’t stop calling me. You know what I mean? And everything that’s in between.

BB: In between, yeah. When I wrote my first book, I had a really difficult conversation with my mom. And she said, “Here it is. You raise your kid and they become a shame researcher and write about growing up.”

BB: And I said, “Yeah,” because shame was probably the parenting tool of choice in my house growing up.

AF: Yes.

BB: And my house was hard and very much, I guess by today’s standards, probably lots of trauma. I didn’t know during the time. I knew it was hard, but I didn’t know. I didn’t know.

AF: Right.

BB: And I remember really wrestling with it and talking to a therapist at the time and she asking, “What do you need from your mom around your work?” And I said, “I don’t think I need anything.” And she said, “Okay. That’s the only answer that’s going to work. So that’s good.” And I said, “If she reads it and she’s pissed, that’s okay. If she reads it and she’s proud, that’s okay. Most likely, she’ll read some of it and be proud and pissed and that’s okay too.”

AF: Yes.

BB: But I will tell you that even how many hundreds of people, Ashley, I’ve interviewed, where we’ve talked about shame and they won’t even write the truth of their story in their private journal, or tell their therapist out of fear that someone may think poorly of a parent. And for me, when I read the book, I just didn’t see good people and bad people, I just saw people. And I saw rage. And I didn’t see an emotion that I have not experienced. Does that make sense?

AF: Absolutely.

BB: And unfortunately, I did not see an emotion that I had not experienced in the midst of probably an important parenting moment, that I fucked up.

AF: I’m sure. I’m sure and I think that that’s sometimes what’s hard for me in these conversations, going back a little bit to my mother, is that I recognize that I’ve written about these really hard and traumatic things and moments that I’ve had with my mother, but I also am so aware that my mother is not alone in a way that she is not.

BB: Yes.

AF: I don’t think my mother always understands that her mistakes and her missteps, acknowledging them is not to encompass her in the mantle of bad motherhood. It’s actually quite common. I don’t want to say normal. Normal to me seems like things that should happen and common are things that just do.

BB: That’s a great distinction that we don’t use enough. So say that again.

AF: Yeah. I think that normal are things that should happen and common is just things that do often happen.

BB: Yes.

AF: And so normal, I think with my mom, I think she looks at the community that we grew up in and the other parents she knew and it’s like the way I raised my kids was very normal. And for me, it’s hard sometimes to have that conversation where it’s like, “Mom, it was common.” A lot of the kids around me were dealing with the exact same thing, absolutely, worse, slightly worse, maybe slightly better. But for the most part, we’re all dealing with the same thing. I get that. But it was just common. It wasn’t normal. It never felt normal to me. I accepted from a very young age that I would be hit, but it never felt normal to me that I was being hit. Ever, ever, ever, ever.

BB: That comes across in the book. My husband and I had this conversation and I thought it was normal, not common, I thought it was normal, but I was not tough enough or I was that bad. But in the page, you can tell there was some subtext to little Ashley. It was, “These folks are losing their minds.” This is like, “I’m the only okay person here.”

AF: It felt like that sometimes.

BB: Where did that come from?

AF: I don’t always know. Sometimes, I’ll be honest, I think it was TV. The combination of TV and books. I was always watching TV or reading. It was just a lot of media consumption. And also as a kid, I was very quick to pick up on patterns. I’d pick up on patterns very, very, very quickly. And you start to notice certain things in movies or in episodes, you notice formulas, you notice the way that things are working out. And in your mind as a kid, what happens in books and TV, the morals of the story are that they are what life is supposed to look like. They’re what life should be. And in movies and TV and in most of my books, parents got mad at their kids all the time, but they didn’t hit them. Not in books and TV. And also, I picked up on the fact that I wasn’t supposed to talk about the fact that I got hit. That if I said something casually, because I had accepted that it would happen and I would say something to another adult, they’d be like, “Oh, what’d you do today?” and stuff. And I’d be like, “I got a whooping.” [chuckle]

AF: I would say something like that. Or, “My mom got mad and I got whooped. I got hit with the belt” or something and I would just say it. And my mother would get so angry with me for telling these people that that had happened to me. And I was confused about it because I’m like, “Wait, so it’s supposed to happen, but I’m not supposed to tell people it’s supposed to happen because it makes you look bad when I tell people that you did what you were supposed to do?” I needed things to line up. I liked patterns. I liked things to make sense. And nothing about my mom hitting me made sense. I couldn’t ever make it make sense. I could accept that it was my fate, that it was my circumstance, that I had no control, but I absolutely could not make it ever feel like, yeah, I deserve this. Like, yeah, this is right.

BB: Wow.

AF: This is what she should be doing.

BB: I started in Catholic school, where we got hit.

AF: Yeah.

BB: Yeah. And then I went to a big public high school in the country in Texas where you could choose detention or swats.

AF: Right.

BB: So hitting seemed at the time… I used to think, “Are we going to read about this one day like we read about Charles Dickens and think, what the hell was going on back then?” Something seems off.

AF: I think we will.

BB: I think we will too. It seemed very ubiquitous, I guess, at the time. I’ll tell you something that I loved about this book. I’ve seen it in memoirs that don’t go back to childhood, but rarely have I seen a memoir where a writer can take you into the secret world of their child self. You had a big world that you lived in that had nothing to do with where you lived.

AF: Yes. Yeah, absolutely. The living mostly in my head, the day dreaming.

BB: Yes.

AF: All of the symptoms of ADHD and PTSD. Yeah, I’ve got them. [chuckle]

BB: Do you think that’s what that is? Because I loved this world full of sun rises and I loved this world that you took us in.

AF: I think that there’s always… Despite the performative parts of my personality, which are more just I’m a theater kid, not like performing life. But I think that that came from the fact that I had that inner world where I was constantly building characters and plays and so many things. When I talk about reading books and watching TV a lot as a kid, I was always doing those things in tandem also. I’d read a book, I’d watch a movie, I’d read a book, I’d watch a movie, I’d read a book, I’d watch a show. And you watch these worlds that are out there, or you read about these worlds that are out there and so much of experiencing them is filling in the blanks for yourself.

BB: Yes.

AF: Because even on TV and in movies, they can’t tell you a whole story.

BB: No.

AF: There are things you have to infer. There are things you have to create for yourself. So even in the watching and the reading, you have to be creatively involved in some capacity. And I just ran with that. I thought that I could play any character on TV. I thought that I could be friends with any character in a book. I really, really did. And I was not a lonely child, I was surrounded by people. I was emotionally lonely. Physically, I was constantly surrounded by people, but I always had… Despite my sensitivity, I had just a little bit of energy to give others and I replenished myself by going into this world in my head, so that I could come back out and be around my family, be around my extended family, my classmates, my friends, whatever it is. In order to come out and feel safe to be out there, I had to create something in me that felt like a safe place to go when the outside didn’t necessarily feel as welcoming.

BB: That makes sense.

AF: And my home was often the place that felt least welcoming, even as it was the place where I spent the majority of my time. So if I was going to end up in situations where I had to be in a room because company was there, whether or not I was very interested in the company or not, it was useful to be able to go to slip back into this place in my head in the moments where I didn’t have to be on, so that I could get the fuel I needed without having to ask for it. Because asking for it would have been too much.

BB: The worlds that kids create, in the best and worst of circumstances, are beautiful places, I think.

AF: I agree. And you know, Brené, one of the things that I’m kind of just realizing, is that so much of the media I consumed as a kid was about adults who needed to reconnect with their inner child. I think about movies like “Hook” starring Robin Williams, where he had no access to any of the magic of Never Never Land until he could remember his child self. He had to be able to reconnect with the child, the Peter Pan inside in order to fly, in order to eat, in order to nourish himself, in order to explore all of that. So much of what we consumed as kids was either about the fact that kids sometimes have to be really strong and resilient, like in Don Bluth movies like “The Land Before Time” or “The Great Mouse Detective” all of these movies that were essentially about, this is the kind of adult you turn into when you disconnect from your child self. When you disconnect from your childhood. You turn into a Cruella, okay? That’s what happens when you disconnect.

BB: Cruella de Vil is the result of this.

AF: Cruella de Vil, right?

BB: Yeah.

AF: And I didn’t want to be Cruella. I didn’t want to be Scar. You know what I mean? I knew that one day I was going to grow up. I knew I had to grow up, even though I didn’t really want to. And I thought a lot about what kind of adult I wanted to be because so many of the adults around me didn’t seem to think about that very much. And they also didn’t seem to think about how their actions actually affected kids and I couldn’t get that out of my head.

BB: So are you saying the adults around you, it was clear that they were not making conscious choices about who they wanted to be and how they wanted to show up?

AF: Yes.

BB: Yeah.

AF: They felt really reactive.

BB: Reactive, yeah.

AF: And that was really hard for me as a child and I didn’t have the language for it then. But I knew that there was something that felt chaotic in a way that made me feel unsafe.

BB: Yes.

AF: Not chaotic in the way that everybody’s family gets a little bit chaotic. Some of the laundry isn’t always going to be done, the dinner isn’t always going to be on time. There’s not always going to be enough money to get everybody what they want or even need. That’s true for a lot of families, but in my family, it seems like there was a lot of people who had given up on trying something new or trying to do it differently and I just didn’t want to forget, I truly didn’t want to forget that there are always ways to do something new or try something differently.

BB: Two-parter.

AF: Okay.

BB: But I want to ask at the same time.

AF: Go.

BB: What was your intention when you started the book? And now that it’s in my hands and getting ready to land in other people’s hands, has your dream for the book changed from what the original intention was?

AF: I want to start by saying, traditionally, I do suffer from a little bit of low self-esteem, low self-worth, working on it every day.

BB: Same.

AF: But it’s in there and I definitely started this book with the dream of it being accepted into a small literary press and maybe having a strong thousand print first run and having my first little book, that was… “I did that, I created it and I wrote it.” And now, as Oprah would say, “I’ve had to learn to dream a bigger dream for myself and for my book” and I really can’t help… Oh my gosh, I cannot help but hope at this point that this is a book that when that weird kid is in the library a lot and the librarian notices them and notices the kinds of books they’re checking out, or the books they won’t check out, but will stay in the library and read, because librarians notice everything, in my dream scenario, this is a book that the librarian would offer that kid and would say, “I think you should read this.” That is my dream, is that that would happen.

BB: It’s beautiful.

AF: I think a lot about just… It’s the transference. I’ve gotten so much from books, just so much of me is made up of the stories I was able to read and share and hold even in myself and the idea that my book could be that kind of book now that my book could be the kind of book that somebody doesn’t necessarily find the answers to the universe in or even the answers to themselves, but where they do find themselves finally just a tiny reflection of the thing that they thought was unknowable or unseeable about them, or maybe something that shouldn’t be seen, I hope it means something to them that I’ve gone through this process to be able to rid myself, truly rid myself of the shame that wouldn’t allow me to value those parts of me and those parts of my story and it has been so hard and it’s still hard, but it feels so good. And if they think, even for a second,

“That might be good for me too.” Even if it’s not my book that gets them there, even if it’s just the book that starts the thought, even if it’s the book that compounds the thought that has already started, what’s better than that?

BB: That’s it, that would be it, right?

AF: Nothing else feels better than that, I’ve had a lot of success in a lot of different kinds of ways, nothing feels better than that. I can say that definitively.

BB: That’s when you feel the most alive, right?

AF: Yes, yes.

BB: I want to read something to you, from the book, is that okay?

AF: Yes, absolutely.

BB: It’s some advice that your mom gave you, I just find it to be profoundly helpful for me personally. She asks you what makes you happy? And you want to give her a true answer, so what you say is, “‘I like making things, art, stories, I want to write.’ I wondered if she knew, when I said I wanted to write that I meant I wanted to write about me, about us, about everything I saw and believed and thought I might know. She let out a breath, ‘Ashley, you’re the only person who has to live in your skin and wake up with the consequences of your choices, that’s why you can’t let other people make the big choices for you, you have to do what it feels right to do and you can’t let anybody stop you,’ I heard her stifled smile again, ‘Not even me.’”

AF: Yeah, yeah, that’s my mom.

BB: It’s powerful.

AF: My mom, I think probably our biggest disconnect is that she thinks the best thing she has to give me is getting out of my life and I can’t change that belief for her and I’m no longer at a place where I try to change that belief for her, but it’s sometimes so nice and lovely knowing that even if I wanted something different, even if I wanted something more, she really has given me her best, that’s undeniable.

BB: God and what liberation there is in knowing that.

AF: It’s taken off the heaviest chain to just be able to accept my mother for who she is, accept the love I have for her the way it is and to sort of let go of the fantasy of who, in my mind, who I wish she had been. But the older I get, the more conversations I have with people I know, people I love, people I even just meet, the more I realize that, if I had gotten what I wanted, it still wouldn’t have been perfect and she’d still be in the book.

[laughter]

BB: And you know what? That is the damn truth. And that is the truth about your book, that’s the truth about my book and what’s really hard is that’ll be the truth about the books that my kids might write.

AF: Oh, yeah.

BB: God dang it.

AF: Oh my goodness. I think about that a lot. If I were to have children, if I decide to have children, which I go back and forth on a lot, they’re going to have something to say about me too.

BB: Oh yeah.

AF: And accepting that, it’s interesting because having to learn how to love my child self has also led to me coming to a place where I’m like, “I think I also have to love and forgive my mother in order to be able to love and forgive myself if I’m going to be a mother. And I should at least practice the compassion with her that I would want to have for myself.” And that’s helped me a lot.

BB: You’re killing me!

AF: I’m sorry.

[laughter]

BB: You’re killing me. I just have to say, again, just for listening, Somebody’s Daughter a memoir by Ashley C. Ford, it is as real as this conversation and you will be invited in. Before we get to… I had to have new rapid fire questions for you because you’ve been on before. But I’ll have you on a hundred times and change these questions a hundred ways, just to be able to keep talking to you. Tell me what does this book mean for your dad?

AF: Now, my dad, it’s strange because, in that direction, it’s almost a weird opposite. My dad is just super proud of me and really wants to read the book, because the book for my dad is an opportunity to get to know me that he is not ever going to have otherwise. There’s just so much time missed between us, that being able to read my book, for him, being able to hear about what my childhood was like from my perspective, I think it really scares him in terms of the emotional factor of having to reckon with why, in some cases, my life was the way it was and my circumstances were the way they were and how he affected those circumstances. But my dad is always a little more excited to get to know me than afraid of what I have to say. And that works out for us really well, because even when he doesn’t necessarily like what I have to say or when he is nervous about what I have to say, he pushes through that as much and as hard as he can so that he can meet me. And that is how he tries to connect with me now, which is nice.

AF: I’ve never really had anybody come into my life in such a way that it’s like, I just want to meet you where you are. I just want to meet you where you are. And so having that has been interesting also for me. So I plan on, after everybody’s vaccinated, driving up to where my dad lives and giving him the book in person. I don’t want to mail it to him, I want to hand it to him. And we will see how he feels after he reads it and finishes it. But I almost thought of this book… When it comes to both my parents, it’s sort of like an opportunity to show my mom, in a certain sense, what growing up was like for me and also to allow her to know that I see her, that I do see her. And I think, on the other end with my dad, I wanted him to have the opportunity to know what he missed and how his missing affected my life. And I don’t know that I could have sat and had a conversation with them that would be more clear than just handing them this book. That’s not why I wrote the book, but it’s a pretty great by-product in my estimation.

BB: Yes.

AF: So I look forward to my dad reading it and I want to be able to talk to him about it. And that’s why, because he’ll talk to me about it. My dad will read it and then he’ll want to talk about it. My mom, I will always be open for the opportunity to talk with her about it, but I leave that up to her. That’s her choice and I’m good with it.

BB: I was re-reading Roxane Gay’s piece, “Writing Into the Wound,” which is a short story essay on… Is it Scribd or Scribed?

AF: I think it’s Scribd, right?

BB: I think it’s Scribd, yeah. She wrote “Writing Into the Wound: Understanding Trauma, Truth and Language.” And there was something that struck me, something she says about writing about trauma and writing our truth in our story. She says, “We share our stories. We try to find the right words. We try to be truthful and fair to ourselves and to others. We try to be free. There is no pleasure to be had in writing about trauma. It requires opening a wound, looking into the bloody gape of it and cleaning it out one word at a time. Only then might it be possible for that wound to heal.” And I just want to say thank you, because it was healing for me and I think the truth-telling in Somebody’s Daughter is so rare and soulful that I have no doubt that a librarian will hand this book to a 12 or 13-year-old girl or boy, who’s maybe hiding what they’re reading in the stacks and taking home something unrelated.

AF: Yeah.

BB: Because I did that a hundred times a year in school. So thank you for that.

AF: Thank you and thank you, Roxane.

BB: Yeah, thank you, Roxane.

AF: Thank you.

BB: Alright, you ready for rapid fire?

AF: Nope, but let’s do it.

BB: Let me just put it this way, as we’re both wiping our eyes at the same time.

BB: You have two choices.

AF: Okay.

BB: You can spend a couple more minutes with me on the rapid fire questions, or just FYI, Ashley is preparing to go camping with her husband, Kelly.

BB: Which made me laugh so hard. That’s love y’all, that’s love, camping. So you could go get ready to camp, or you can answer some questions.

AF: You know what, Brené? We should answer these questions. It’s really important.

AF: I think it’s really important for us to get to these rapid fire questions.

BB: Yes. It might take all weekend.

AF: It might. And if it does, I’m sure he’ll understand. I’m sure. I’m going to say, “Baby, Brené needs me.”

AF: And he’s going to be like, “No, I don’t accept that.”

BB: Right.

BB: Fill in the blank for me. And don’t think that these are the ones I asked you last time. We got all new hard ones. Okay.

AF: Okay, I’m ready, I’m ready.

BB: Fill in the blank for me. Your purpose is?

AF: My purpose is to live this life as much and as well as I can.

BB: Dang! What makes you laugh the most?

AF: What makes me laugh the most is people with really dry senses of humor, when nobody else heard the joke but me.

BB: And you know what? Little Ashley liked that too.

AF: Yes, she did. Yes, she did.

BB: Way before her time.

AF: Absolutely. I think it was all the night time “Golden Girls” that really did that to me. [chuckle]

BB: You love some “Golden Girls.”

AF: I do, I do. It’s in my DNA at this point.

BB: Okay. When you can go somewhere, like COVID-wise, where are you looking forward to going. Where do you want to go, if you could go anywhere?

AF: I want to go back to the Lake District in England and visit the home of Beatrix Potter.

BB: I would so go with you.

AF: It’s amazing. I’ve gone one other time. I went in 2016 and it is my dream to go back to the Lake District, which is basically Beatrix Potter Land and it’s nothing but sheep and literary references for miles and miles and miles.

BB: That’s where… If I’m really good the rest of my life and die and go to heaven, that’s where I’m going, somewhere just full of sheep, rolling moors, and literary references.

AF: And B&Bs with extremely deep bathtubs and five-star restaurants attached to them.

BB: Oh God, Jesus.

AF: It’s wild. It’s exactly the kind of vacation I want. I want to walk among the moors with the Herdwick sheep and then I want to go learn more about Beatrix Potter, who I think is amazing and fascinating.

BB: She’s a badass feminist from the word go.

AF: Yeah, she is.

BB: Yeah.

AF: Yes, absolutely.

BB: Don’t let the bunnies fool you.

BB: Okay, what is your go-to karaoke song?

AF: Oh, “You Oughta Know” by Alanis Morissette.

BB: Sorry. I could see you singing it. It would be fierce. Okay.

AF: Yeah, I’d lose it.

BB: In my dream vacation with you, when we go to the Lake District, there’s going to be a karaoke bar. Okay.

AF: Yes. Yes.

BB: Alright, what’s a song that you would risk life or limb to turn off the radio when it comes on?

AF: Oh, this is hard. I like so much music. I don’t even think about what I don’t like. Is there a song I really, really don’t like? Oh my God, actually, yeah. There’s this song by this guy named something, James, James something and it came out years ago and it’s called “You’re Beautiful.” And it’s like he sings in this falsetto voice like.

[vocalization]

AF: “You’re beautiful.” It’s really… I don’t know and I don’t like it at all.

[laughter]

BB: On the opposite end of the continuum.

BB: Okay, you’re going to need to really explain your Kenny Loggins thing to me. [laughter] Come on.

AF: I can’t. I love him so much. He is the sultan of soundtracks. He just… The melody, the smoothness of his voice. He’s the king of yacht rock.

BB: Oh, yacht rock.

AF: It’s really like him and Christopher Cross out here battling for the crown.

BB: Oh, Michael McDonald, would you put them in there?

AF: Michael McDonald, I would put Michael McDonald on his own into yacht rock, but I would Michael McDonald with The Doobies into yacht rock. But Michael McDonald on his own is pretty much blue-eyed soul.

BB: That’s it, yeah.

AF: He’s well into the blue-eyed soul situation. But when he’s with The Doobies, which by the way, The Doobies are coming here this summer and I’m pretty sure Michael McDonald is going to be with them. So you might catch me out in the crowd this year seeing The Doobies. But the Kenny Loggins thing, specifically, comes from a fascination a childhood situation where I had a hard time getting to sleep and his tapes helped me get to sleep. But then, that just grew into this fascination. In my mind, I think he became like a father figure. So much of his songs, especially his lullaby albums, are essentially a parent singing to their child. And the songs that he chooses are all a parent singing to their child. The songs that he writes for those albums are him specifically singing to his children. And so I would play these albums and feel like somebody was singing to me and cared that I was scared at night and would sing me to sleep. And I just never got over it. Eventually, it became less of an emotional thing and more of a, “This guy rocks, actually.” I just really love his music. I love “Danger Zone.” I love…

BB: Oh, I do too.

AF: All his albums. I listened to the Vox Humana album. Nobody knows Kenny Loggins has a Vox Humana album, I do. That album is fantastic and I listen to it all the time.

BB: You are deep into Kenny.

AF: I am.

BB: If we went to a karaoke bar and you did Alanis Morissette, do you think you and I could pull off a duet of “This Is It?”

AF: We could absolutely pull that off. We could also pull off “Whenever I Call You Friend” which is his duet with Stevie Nicks.

[vocalization]

BB: Whenever… Oh my God, that’s a good one. Okay. Alright.

AF: Yes, yes.

BB: What’s one thing you’re really excited about right now besides camping?

AF: Not camping. No, I am really excited about the virtual tour for my book. I am really excited about the people that I’m going to be talking to on that virtual tour. I’m really excited to be able to answer questions from readers who read the book, which is something that, with the pandemic, I was so worried about. Like how is that going to work? I want to be able to connect with my readers and being able to finally do that and have the book finally be out and have those conversations which are going to be challenging and beautiful and brutal at times, I’m sure. I’m just ready for it. I’m really excited for that part. I’m excited for the conversation part.

BB: Ah, it’s going to be good. Okay, what’s one thing you’re deeply grateful for right now, besides camping?

AF: I’m really grateful for the fact that I am not required to feel good about myself to have good things in my life. Because I haven’t always felt really good about myself and I don’t always feel really good about myself right now, but I always have such good people around me at any given time, that I don’t have to feel good every minute of every day. I got good people who can sometimes feel good for me and help me find my way back. That’s enough, man. That feels amazing.

BB: That’s a gift.

AF: It feels like a gift.

BB: Yeah. Alright, we asked you for five songs you couldn’t live without for the mixtape. I really, really love your mixtape. Next time Spotify lets me take over the yacht rock playlist, maybe you and I can co-create it together.

AF: Please don’t say things to me, because my heart will explode just at the idea of creating the yacht rock playlist.

BB: Yeah. I know, I think we should do it together. It would be so fun.

AF: Yes.

BB: For your mixtape on Spotify… First song, I can’t even say without crying, “Gentle On My Mind,” by Glen Campbell.

AF: Yes.

BB: “Call On God,” by Sharon Jones & the Dap-Kings.

AF: Yes.

BB: “If I Could,” by Regina Belle.

AF: Yes.

BB: “This Is It,” by Kenny Loggins featuring Michael McDonald.

AF: Always.

BB: And “On and On,” by Gladys Knight and The Pips.

AF: Yes.

BB: This is your writing challenge. One sentence. What does the playlist say about you, Ashley C. Ford?

AF: The playlist says that I’m down for a good time and I think a good time is a real time.

[laughter]

BB: Oh, God. Boom. Boom. Go back to the first question, when did you know you were an eloquent and powerful writer? When she gave me one sentence for her mixtape, damn. That was good. Wow. It is always just such a privilege to talk to you. I appreciate you being on the podcast again.

AF: Mutual. It’s so mutual, Brené. Thank you for having me. Thank you for being encouraging and supportive. It means the world and I know you know how much it means. So, thank you.

BB: God, I loved Somebody’s Daughter. You need to go get it. You can buy it wherever you buy books. We love our indie booksellers, so make the extra one second effort to buy it from an independent bookseller. Because if you’re like me and you need to order it and have it delivered in 30 minutes and then it sits on your night stand for six months, eh, let’s support some indie bookstores. You can find Ashley online. Her website is ashleycford.net. Her Instagram… I laugh because I’ve followed her on Instagram for a long time, is @Smashfizzle, S-M-A-S-H-F-I-Z-Z-L-E. And Twitter is @Ismashfizzle. Okay, don’t forget, we’re going to be taking a couple of weeks off. You can find all the links to Ashley Ford’s book and her playlist, everything you need on brenebrown.com. Just click on the podcast link and it’ll take you to everything you can imagine Podcasts. We are exclusively on Spotify, that’s where we keep our playlists and our podcasts. I’m grateful for y’all. Stay awkward, brave, and kind.

BB: Unlocking Us is a Spotify original from Parcast. It’s hosted by me, Brené Brown. It’s produced by Max Cutler, Kristen Acevedo, Carleigh Madden, and Tristan McNeil, and by Weird Lucy Productions. Sound design by Tristan McNeil and Andy Waits. And music is by the amazing Carrie Rodriguez and the amazing Gina Chavez.

© 2021 Brené Brown Education and Research Group, LLC. All rights reserved.