Brené Brown: Hi, everyone. I’m Brené Brown, and this is Unlocking Us.

[music]

BB: Before we get started talking about this conversation that I had with Dr. Clint Smith, which is just… I will tell you that we have this big review process within our organization before a podcast goes out. A lot of people listen to it, we do a lot of work on it. And then we have another group of people that listen. And one of my colleagues, Murdoch, just sent a note in Slack that said, “Jaw-dropping.” And I think it’s a great descriptor of this conversation with Dr. Clint Smith.

BB: Before I tell you a little bit about what we’re going to talk about, I want to give you a couple of announcements. One, that Unlocking Us is taking off from June second to June 16th. I’m actually finishing some new research and finishing a book that’s going to be coming out later this year. We’ll be back on June 23rd with a five-part summer series that I’m doing with my sisters, Ashley and Barrett, on The Gifts of Imperfection. Barrett, are you excited about the summer series?

Barrett Guillen: Oh, I’m so excited!

BB: She’s so excited. She’s looking at me because this is what I’m going to say next. She’s looking at me like she’s in her smartass tone because I’m getting ready to say: Dare to Lead’s going to be taking off from May 31st to July 5th. And then I’m coming back with a two-part solo series on the hardest feedback I’ve ever received. And I was just thinking I would invite Barrett to that one as well, and you could share the hardest feedback you’ve ever received.

BG: I cannot wait.

[laughter]

BB: That’s her lie voice, just in case you don’t know. But we will be back. We’re taking a hiatus. Catch up on episodes, relisten. And then when we come back, we just have this kickass line-up of conversations and podcast ideas that I cannot wait to share with you.

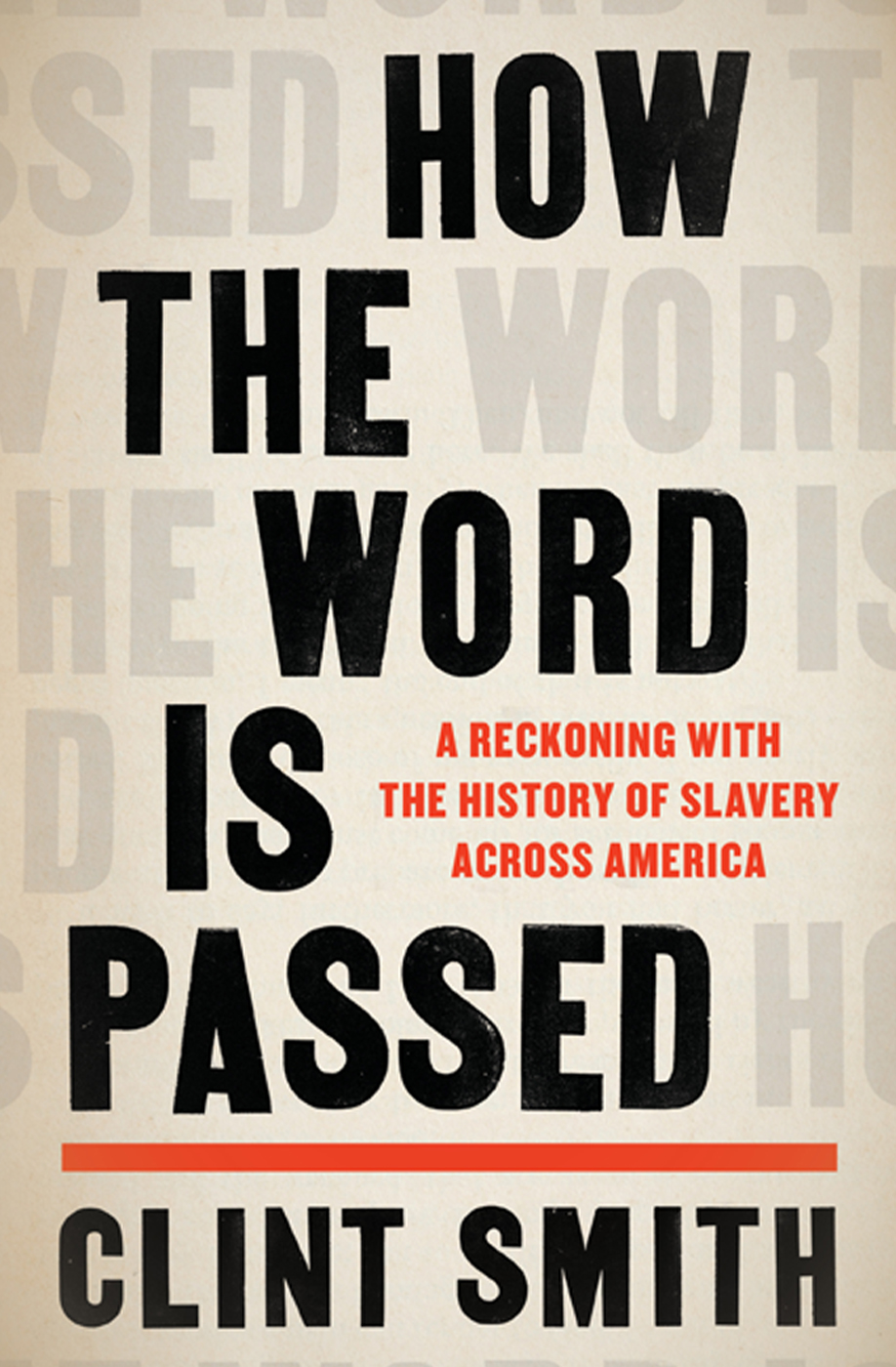

BB: Let’s talk about this conversation with Dr. Clint Smith and his new book, How the Word is Passed. Clint is a scholar, he’s a writer, he’s a teacher. And his new book, How the Word is Passed: A Reckoning with the History of Slavery Across America, is just… I’m going to go back to jaw-dropping. I think I start the podcast by just saying, “I don’t understand. I don’t understand why I didn’t know this. I wanted to be a History major. Help me understand how I didn’t know what you’re writing about in this book.” We really talk about the history of slavery in the United States, how we approach, excavate, recognize, and react to that history, how we have a responsibility and accountability to get the story and the history right, what happens when history is erased and becomes ideology. It is one of the most important conversations, I think, we’ve had on Unlocking Us. When we can be honest about history, when we acknowledge it, when we reckon with it, we can start to change and heal. And there is no better guide to walk us through this, I think, than Dr. Clint Smith. I’m glad y’all are here.

[music]

BB: Before we jump into our conversation with Clint, let me tell you a little bit about him. It’s Dr. Clint Smith. He just recently finished his PhD in Education at Harvard. He is a staff writer at The Atlantic, and author of the poetry collection, Counting Descent. The book won the 2017 Literary Award for Best Poetry Book from the Black Caucus of the American Library Association and was a finalist for an NAACP Image Award. He has received fellowships from New America, the Emerson Collective, the Art For Justice Fund, Cave Canem, and the National Science Foundation. His writing has been published in The New Yorker, The New York Times Magazine, Poetry Magazine, The Paris Review and elsewhere. Born and raised in New Orleans, he received his BA in English from Davidson College and his PhD in Education, again, from Harvard. Let’s jump into the conversation.

[music]

BB: So Dr. Clint Smith, let me just start by saying welcome to Unlocking Us.

Clint Smith: It’s a pleasure to be here.

BB: I’m just going to say right off the bat that I’m not going to get through this conversation probably without crying, so I just am going to put everybody on warning that… Every now and then, I read something and I think I want to buy everybody… Because sometimes, it’s everybody I know, sometimes, it’s my friends, and sometimes, it’s I want to buy everybody in the world a copy of this book and I want to exert what little power I have to make it mandatory reading in every high school. How the Word is Passed is that book for me.

CS: That’s very kind of you to say, truly.

BB: You and I have… I don’t know, we’ve been friends online, we comment on each other’s things, and I was so excited when you defended your dissertation and you got your PhD, but I don’t think I knew what you were up to.

CS: Yeah, this has been four years in the making. I made the strange decision to write a book and a dissertation at the same time, which I don’t recommend, but it happened that way. And so the book, I started in 2017, and the dissertation, again, in many ways, around the same time. And I graduated from my PhD program at the beginning of the pandemic, so April of 2020, and that was when Zoom was still a novelty, when it was still sort of exciting and like, “Oh, Zoom!” And I will say it was an amazing feeling to be able to celebrate my dissertation defense with family and friends who never otherwise would have been able to fly up to Harvard to see it for themselves. Because usually, these things are really small and intimate, and you only have a few people in the room, and it became this thing where hundreds of people from our life…

BB: Right.

CS: I mean the neighbors I used to mow the lawn for, the person who babysat me in second grade, family, friends that I’ve known my entire life, and grad school friends from just a few years ago, it was such a beautiful sort of collage of folks. And so I mourn the fact that I didn’t get to walk across the stage or wear the fancy robe or anything like that, but I am grateful that I was able to share that moment with a community of folks who made that moment possible in so many different ways.

BB: So many sets of fingerprints on that degree, huh?

CS: Exactly, exactly.

BB: Yeah.

CS: It’s from my second-grade teacher to the folks who let me borrow tea when we were staying up until 2:00, 3:00 in the morning, studying for our qualifying exams. You know how that doctoral life is.

BB: I do.

CS: Living off with caffeine and pizza. And so that was how it went. [chuckle] But yeah, I’m grateful, I’m grateful for that time, and I’m grateful for those years. This book is not directly emerged out of my doctoral work, but it most certainly wouldn’t have been possible without those years and that time that I got to spend just reading and writing and thinking, and being able to study across departments.

BB: Yes!

CS: Some of the most formative classes that I took… My degree is in Education, but some of the most formative classes that I took were in African-American Studies with people like Dr. Brandon Terry and Tommie Shelby, and history with Walter Johnson. And the interdisciplinary nature of those six years, I think, made it possible for me to imagine writing a dissertation about the relationship between mass incarceration and education, and then writing a book about slavery and public history, and how we remember and what we remember.

BB: I want to start with a question that we always start with because it speaks to what I love most in the world, maybe, but can you tell us your story?

CS: What is my story? I was born and raised in New Orleans, Louisiana, and New Orleans is in me, in every bone of my body, in ways that I think I’m still figuring out, in ways that I’m still learning about. Hurricane Katrina was my senior year of high school. And so I was three days into my senior year of high school and end up in Houston, Texas, actually. And my two younger siblings, my sister and my younger brother, we were enrolled at a private school in Houston. It was very different. We’d attended public schools our entire life in New Orleans, and it was this moment of experiencing race in class in a way that I had never encountered before. Even when I didn’t necessarily have the language to name it or the sort of sociological framework to understand it, and the history that created it, I was sort of experiencing, first-hand, how the arbitrary nature of birth and circumstance shapes the outcomes of people’s lives. I was in this place where, that I’m very grateful for, but where the expectations around what people would go on to do with their lives, what kind of schools they would go on to attend were deeply tied to the financial and economic resources that they grew up around.

CS: And I think all the time about how that has become, in many ways, the sort of central animating framework or notion around how the world moves in my life, in which you can have two young people who are born into fundamentally different circumstances, who work equally as hard. And if one person is born into a set of circumstances in which they are born into a community that, over the course of generations, have become saturated with poverty and violence, for a range of different reasons, tied to a history of public policy decisions. And then you have another young person who grows up in a community where they feel safe, where they feel loved, where they feel affirmed, where they have all the resources, and social and economic capital they need. It’s not a question of who works harder or who doesn’t work harder. It’s a question of who has been afforded the resources and capital that will put their lives on a certain trajectory. And so I think witnessing the sort of landscape of public education in New Orleans, and then going to this very fancy private school in Texas helped me experience and understand that first-hand in a way that I think I only would have understood in the abstract, otherwise.

CS: And so I graduated. I went to Davidson College. I played soccer my entire life, so that’s the larger context, is that from age four to 17, I thought I was going to be a professional soccer player. And I was obsessed with Thierry Henry and Arsenal, and I was like, “I’m definitely going to be a pro soccer player, and live in London, and everything’s going to be amazing.” And then you grow up and you realize that Louisiana is not necessarily a hotbed of global soccer talent in which to measure your skills. And so I had a skewed sense of how good I think I was, growing up. Because I was like, “All-state, all-city, I’m in the paper,” I was that guy. It was so central to my identity; it’s all that I cared about. And then I went to Davidson, and I got a soccer scholarship to play at Davidson, and then it’s a small school, but it’s a Division One school. And I never played. And I sat at the bench, basically, for four years, and had this sort of 18-, 19-year-old existential crisis, where this thing that had defined me for so long in my life, I was no longer good at. And I realized how much of a sense of purpose and value being considered a good soccer player gave to my life. And when that was taken away, I felt really untethered and I felt really unsettled.

CS: And so part of what I’m grateful for is that I was at a place like Davidson, a small liberal arts school, in which the expectation of the student athlete, 20% to 25% of the students there are student athletes because it’s so small. When I was there, it was only 1,600 people. And they really encourage you to figure out who you are off the field. And so I had the opportunity to write for the student paper, and join a fraternity, and do work with Big Brothers Big Sisters, do a lot of work in the local community, and things that helped give me a sense of who I could be and what I wanted to do in the world outside the context of thinking I would be a professional soccer player.

CS: And in 2008, I had an internship in New York City at a publishing company. And I was with a group of interns, and one of my friends, one named Mariana Sheppard, she was a fellow intern. And one night, we all hung out and we were going to go somewhere in the city, and I think we were going to go see a movie. And then Mariana was like, “Let’s actually go to the Nuyorican Poets Cafe.” And I was like, “The what, a what?” Like, “Nah, I don’t want to go to the Nuyori, the Nu, the, whatever you’re saying. I want to go… Let’s go see Mission: Impossible 2, Tom Cruise out with a new movie, let’s go.” And she’s like, “Clint, shut up. Come on, let’s go.” And so she took me to the Nuyorican Poets Cafe, which is on the Lower East Side of Manhattan. And this is… More context is that I was struggling because I wasn’t playing on the soccer team. I was a sort of disillusioned English major who thought I was a good writer, but then was studying all of this work that made me feel like I wasn’t. And I just felt really, again, really untethered.

CS: We went to the Nuyorican Poets Cafe, it was a Friday night, and I had never experienced anything like that in my life. The Nuyorican is one of the most legendary poetry cafes in the country, where slam poetry, spoken word, performance poetry competitions and open mics happen. And it was just this room of Black and brown and queer people, and you step inside and Bell Biv DeVoe is playing, New Edition is playing, people are dancing to Poison with drinks. And I was like, “This is a poetry reading? What is happening?” I’d never seen anything like it. And the woman got on stage… And I remember one of the first poems I ever heard was by this woman who had cerebral palsy. And she got on stage and did this poem, and in three minutes, the way I thought about an entire demographic of people completely changed. I left that evening never thinking about disability the same way again because I had been so profoundly moved by this piece of art.

BB: Wow!

CS: And I was like, “I didn’t know art could do that.” I had never been so viscerally moved by art in my life. I had never been that moved by literature in my life. And then I would go back to the Nuyorican sort of every week for the remainder of my time there. That evening opened up the possibilities and expanded my conception of what literature could be at a moment where it felt so small, and it previously felt so small and so limited to the canon that previously, I was like, “Well, I’m reading Keats and Yeats and Frost and Whitman and all these folks,” and I was having a difficult time as an 18-year-old connecting with them. And I think part of what happened is that I was putting the pressure of an entire genre onto those poets. I was like, “Well, if you don’t write like this, or if your poems don’t sound like this, then you’re not a poet, or you don’t like poetry.”

CS: And the Nuyorican helped me understand that poetry was so much more expansive than what I had been presented with. And it, interestingly enough, made me go back to those folks in the canon and appreciate them differently and appreciate them more so because I was like, “Okay, when I read Leaves of Grass, I can appreciate it for what it is because this is not the entirety of what poetry is. With any piece of art, I think you look at it and you experience it in ways that are specific to what that art is offering you.

BB: Yes, and I wonder, too, if you can read it for what it is, as opposed to a measuring stick of whether you’re going to be able to be a good poet or not, or a good writer.

CS: Exactly, right, yes, so…

BB: Wow! Wow, what a night that was!

CS: It changed everything. Every time I would… When I was able to travel, I haven’t been in a plane in so long, but Mariana is still in New Orleans, and sometimes, I get together with her over coffee. I’m just like, “I’m so glad… [chuckle] You have no idea how glad I am you didn’t let me go see that Tom Cruise movie that night. Imagine if we just went to see Mission: Impossible 2?” No, it changed everything. And so I went back to Davidson and I put all of the effort that I’d been putting into soccer in my life, and I put it into writing. And I started a poetry club where we did our sort of cosplay of the Dead Poets Society, and we got together in the main academic building on Sunday evenings, and we wrote, and we shared our work, and we practiced, and we watched other poets. And it was such a unique, eclectic group of people, like physics majors who just wanted to experience what it was to write poems in community with folks, people who had done this for years, people who were, alongside me, sort of relearning what art and literature could be and what our relationship to it could be.

CS: And then, graduated from Davidson. I lived in South Africa for a year doing public health work around HIV/AIDS and tuberculosis. And then I came back to the States and I started teaching in Prince George’s County, Maryland, and I was a high school English teacher. And when I started teaching, I was like, “Okay, this is it. I’m good.” I really thought that I would be a high school English teacher for the next 40 years. To me, there’s nothing better than sitting around with a group of teenagers in a circle, reading and discussing literature and books. It was just so… I loved it so much. And part of what happened is that the more time I spent in the school with my students, the more interested I got in the sort of larger sociopolitical and historical landscape that was shaping what my school community looked like. And this was a large urban school district, the majority of kids are Black and Latino. The vast majority of them are on free and reduced lunch and so, the typical story of many of these large schools and school districts.

CS: And this was a moment where some of the discourse was that education is the civil rights movement of our time, or the civil rights issue of our time. And it was centered that way in a way that I felt was not putting it in conversation with the larger ecosystems of social and political and historical realities that it’s a part of. And so I ended up spending a lot more time reading about the history that was shaping what my community looked like, and trying to understand better for myself that how the reason that some of these kids show up to school without food to eat or go home to communities that are plagued with gun violence. It has nothing to do with the people in those communities. It is because of things that have been done to those communities over the course of generations. I got really interested in critical pedagogy, spent a lot of time reading folks like Paulo Freire.

BB: Paulo Freire, yeah.

CS: Yeah. And that school of thought became really transformative for me as an educator. Because for me, one of the most powerful things education can do is to help young people understand that the world is a social construction, and thus, can be reconstructed and deconstructed and made into something new. And you don’t have to accept the current reality of the world as an inevitability, but as something that was created and can be recreated, and reconceptualizing all of our own agency in the potential to build new communities and to build new worlds. And I think that’s not only important for young people, but that’s important for all of us.

CS: And so I got really interested in that, and then I applied to grad school because I wanted to think more about that. And I got into Harvard’s new interdisciplinary PhD in Education program. And I went up there, and I actually started the same week Mike Brown was killed in Ferguson. And so that, if we’re going to think about the beginning of Black Lives Matter movement, in many ways, it began with Trayvon Martin, but if we’re going to think about that iteration of it beginning in 2014 with Ferguson, that animated my entire graduate school experience.

CS: And so as I was sitting in the library for 12 hours a day, thinking about these texts and thinking about the things that I was studying, it felt like the world was on fire around me, and I wanted to figure out how to be closer to, and feel more proximate to what was happening. And also just trying to figure out how I fit in to all of it. And one thing that became clear to me is that I’m someone who needs to be constantly reminded of, and engaging with the sort of real-world stakes of the thing that I’m studying because if I sit around reading Foucault all day in the library, that’s cool, theory is good and helpful. But if I’m not spending time with incarcerated people, then I’m actually losing touch with the reason that I’m studying this thing in the first place.

CS: And so I started teaching in prisons in Massachusetts, and I’ve been teaching in prisons and jails ever since. And that was also a really transformative moment for me because you’re just like, “Oh, these are people. These are people who were born into a set of circumstances that many of us could just never imagine.” And again, going back to the beginning of what I’m realizing is now a long story, it’s the arbitrary nature of birth and circumstance. The people that I’ve spent time with and met in prison, the vast, vast, vast majority of them have been born into poverty and born into community saturated with poverty and violence in ways that I became acutely aware of. Had I grown up in those similar circumstances, I would have almost certainly been in the same conditions that they were.

CS: And it was just a really important and profound reminder that what happens to us, certainly, we have free will, certainly, we have agency, certainly, we are people who make decisions in the world that we are responsible for. And also all of that agency and all of those decisions are animated by things that happened a long time before us, and that had nothing to do with us. And I think that that has stayed with me in everything I do. And so then, spent the last six years in grad school, graduated in 2020, married in the suburbs of Maryland, got two small kids, and just finished a book called How the Word is Passed.

BB: I guess like all of our stories, but it just seems so poignant in yours, what a collection of sliding-door moments. What a collection of moments where had you gone to see Mission: Impossible 2. And I wonder, too, as someone who was raised in New Orleans and lives in Houston, and I know that relationship that we have with each other, would things be different had you not come here for high school and started thinking about circumstance and think about… Just a story filled with moments where they were so defining, do you think?

CS: No, absolutely. That’s one of the things that I think about a lot. I’m obsessed with that idea of the butterfly effect.

BB: Oh, yeah!

CS: This idea that you’re speaking to where this one… Sometimes, there are huge things, but they don’t feel huge in that moment. In that moment, in the summer of 2008, when we’re deciding to go to a poetry cafe I’d never heard of or a movie, how could I have ever known that it would be as consequential as it ended up being? And our lives are just full of millions of those moments in ways that some of them, that we’re able to see, in the way that I’m able to look back and see, that that decision was clearly a turning point in my life. But I’m also aware that so many of those small moments are things that I’ll never be cognizant of.

BB: No, that’s right.

CS: Small moments that changed my life. And we also… These are just decisions I’ve made. That doesn’t even take into account all of the decisions that other people make, or things that other people do that touch me in ways that I am not and will never be aware of, that also shaped my life in profound ways. So I just try to always move through the world with a sense of humility and the sense that so much of this isn’t up to us.

BB: Yeah! Thank God! [chuckle]

CS: And I think that that can be scary for some folks, but I also think that it can be freeing.

BB: Yes.

CS: And I think it’s also just a more honest reflection of how the world works.

BB: That’s right.

CS: Because otherwise then, we’re sitting here having conversations about: If people are living in poverty, is it their fault, or is it not their fault? That are deeply ahistorical and that are blaming people for circumstances that are reflective of things that they had nothing to do with. And that shapes our political discourse and our policy discourse and the material conditions of people’s lives every day.

BB: You know what’s so funny, as we’re sitting here talking and you’re mentioning Paulo Freire and Foucault, and I was like, “I studied those things. And why did I study those things? Because you know I have a Bachelor’s, Master’s, and PhD in Social Work. Why do I have those things? Because I wanted to be a History major, but the only parking spot I could find on the UT campus was in front of the social work building, so I had to walk through it to get to the history building.”

CS: Oh, wow!

BB: And when I got to the history building, they were all white old guys with huge foreheads. And I couldn’t really find myself there. And so I had to walk back through the social work building, and they were having a work stoppage because the students did not agree with the pay that the adjunct professors were getting. And I was like, “Is this a major?”

CS: Yeah!

BB: And that’s how I ended up there. But I have to say, transitioning to your book, How the Word is Passed, for someone who loves history and has read a lot of history, you blew my mind.

CS: Thank you so much.

BB: If there was an emotional triad in reading your book, it would have to have been rage, grief, and gratitude. I just bounced around from rage to grief to gratitude. So how do you explain the book to folks? So the folks listening who I insist y’all buy this book. I don’t think I’ve ever said that, but it’s… How do you describe this book to people when people say, “Tell me what your book’s about”? What do you say?

CS: So in 2017, the statues, several statues in New Orleans were coming down, the majority of which were honoring former leaders of the Confederacy. And so this is in the month of May 2017, and over the course of a few weeks in May, the city took down the statues of Robert E. Lee, Confederate General P. G. T. Beauregard, Confederate General Jefferson Davis, former Confederate President, as well as some others that were tied to the legacy of the Confederacy and white supremacy.

CS: And I was watching these statues come down in my home town, and I started thinking about what it meant that I grew up in this majority Black city in which there were more homages and more iconography dedicated to enslavers, rather than enslaved people. What did it mean that on the way to school, I had to go down Robert E. Lee Boulevard? What did it mean that to get to the grocery store, I had to go down Jefferson Davis Highway? What did it mean that my middle school was named after a Confederate leader? What does it mean that my parents live on a street today named after somebody who owned 150 enslaved people? What does it mean that tens of thousands of Black children, hundreds of thousands of Black children over the years went to a school named after somebody who was a supporter of the Confederacy and a staunch segregationist? What does it mean that one of the plantations I went to on school field trips didn’t say anything about… Didn’t say the word “slavery.”

CS: And so I started really reflecting back on my own childhood and how I was surrounded by this Confederate iconography and symbols and memorials and iconography dedicated to people who enslaved human beings, and thinking about what the implications of that were. Because we know that symbols and names and monuments and memorials, they’re not just symbols.

BB: No.

CS: They are reflective of stories that we tell. And these stories that we tell shape the narratives that are embedded in societies. And those narratives shape public policy, and public policy shapes the material conditions of people’s lives. And so a 60-foot tall statue of Robert E. Lee is not just a 60-foot tall statue of Robert E. Lee. It is reflective of something much more deeply ingrained in a sort of society’s collective memory and understanding of itself. And so I was thinking about that in New Orleans, and then I started thinking about it more broadly in the United States. And so I started considering what are the ways that different parts of this country actively reckon with or fail to reckon with their relationship to the history of slavery.

CS: And so I had started traveling to different places across the country, the plantations, prisons, monuments, memorials, houses, cities to try to understand what places were confronting that history directly, what places were running from it, and what places were doing something in between. And ended up going to eight different places across the country and across the ocean that reflect the variety of ways that this country both grapples with and fails to grapple with the history of slavery and how it shapes the contemporary landscape of inequality.

BB: There’s no question you’re a writer’s writer. You’re poetic and lyrical, and you’re, and the way that you communicate, you’re a storyteller. And your writing… I was talking to Laura, my colleague who we read the books together and we prep and talk together. And we were like, “What’s the word?” And she’s like, “I don’t know, it’s a big word, whatever the word is.” And I think we came up with the word “cinematic.” Your ability to bring us to a place, and I smell that place, and I taste that place, and I can move my feet around in my shoes, and I feel the dirt under my feet in that place, and it is incredible how you take us on this journey with you.

CS: That means a lot, and I’m so glad to hear that because that was the hope. I’ve spent so many years, and part of what created the desire to write this book was having spent years deeply-embedded in the historiography of slavery. And books like Annette Gordon-Reed’s The Hemingses of Monticello, books like Leslie Harris and Ira Berlin’s Slavery in New York, books like David Blight’s Race and Reunion, books like Daina Ramey Berry’s Price for Their Pound of Flesh. These books that have just transformed my understanding of this country and its history. And part of what I wanted to do was take the best of this remarkable history that I’ve been so lucky enough to spend time with over the last several years, and think about what it would mean to add human texture and emotional texture. And to take a book like Annette Gordon-Reed’s Hemingses of Monticello, and to go to Monticello, and think about, to your point, what does it look like? What does it smell like? What does it feel like standing on that land? Who are the people who are responsible for telling the story of this land? What do they look like? What do their voices sound like? What are their backgrounds? What are their stories?

CS: And to try to bring all of that together to create a sort of poetic and literary texture that is in conversation with this history that has just been so important and transformative for me, personally, and that I hope will be transformative for others. And I think that my background as a poet has trained me to think about things in the most granular way possible, thinking about the specific ways that the dirt falls across the path, thinking about the specific ways that the branches move when the wind blows, thinking about the way that a slice or a blade of light will slide into and onto the floor of a slave cabin, and what that reflects and what that tells us about the conditions that people lived in. So yeah, I wanted to just include as many details as possible. I wanted the reader to feel like they were there with me. And I wanted them to experience this place and these places as I was experiencing them.

BB: So I thought long and hard about how we were going to approach this conversation because I had so many questions for you, and then I’m like, “Oh, my God! This is like you trying to talk to him about sociological discourse and research, and that’s not what we’re trying to do.” But I want to walk in to just a couple of the chapters and stories. Let me ask a more general question to start with, and then I thought we could walk into Angola Prison together.

CS: Yeah.

BB: I thought you could take us in in the way that you’ve done so beautifully. Before we get there, why am I so shocked? I read broadly. I’ve studied history. Why am I so devastatingly shocked when I read about these stories and these places and these histories? I have no control over source material for my education. Let me just say that first. The disinformation campaign. I’m shocked. Why am I shocked?

CS: There’s a Southern Poverty Law Center study from, I think 2018, that showed that only 8% of US high school seniors at the time were able to identify slavery as the central cause of the Civil War, 8%. The other 92% thought it was a whole range of things, but only 8% were able to identify slavery as the central cause of the Civil War. And I remember reading this survey and seeing myself in it, because I grew up in Louisiana surrounded by Confederate iconography everywhere I looked. In my Louisiana history class, in my American History class, never having been taught, what should be one of the first things said when teaching about American history in this country is that, for example, the Confederacy was a treasonous army that fought a war predicated on maintaining and expanding the institution of slavery. And the insidiousness of white supremacy and systemic racism and the Lost Cause is that it turns that statement, it transforms it from an empirical one to an ideological one.

BB: Okay, wait, I want you to stop right there. I want you to back up a little bit, if you don’t mind, and say that again in a really methodical way because it is so important.

CS: So part of the project of the Daughters of the Confederacy following the Civil War, of the Lost Cause that would go on to misrepresent what the war was fought over, and the sort of larger history of white supremacy in this country is that it attempts to turn empirical statements into ideological ones and political ones. So a statement like, “The Confederacy was a treasonous army predicated on maintaining and expanding the institution of slavery.” Suddenly, that becomes a statement that is reflective of an ideological disposition, rather than one that is actually grounded in empirical evidence and supported by primary source documents. Because we don’t have to look very hard to understand why the Confederacy seceded from the Union because they said it for themselves. In 1861, they all had these declarations of secession at these secession conventions where a state like Mississippi in 1861 says that, “Our interests are thoroughly aligned with the institution of slavery, the greatest material good in the world.” So they were not at all vague about why they were leaving the Union.

BB: No, explicit.

CS: They were quite explicit. In Alexander Stephens’ Cornerstone Speech, Vice President of the Confederacy, where he said the cornerstone of our new nation is the inferiority of African people and the project of perpetual enslavement. That is the essence of what he said. And so a comment like, again, “The Confederacy was a treasonous army predicated on maintaining and expanding the institution of slavery,” is not something that is reflective of my political sensibilities. It is actually just something that’s historically accurate. A part of what racism tries to do is turn empirical evidence into ones that are ostensibly reflective of someone’s opinion and reflective of a political sensibility or disposition, rather than one that is honest about this country’s history.

BB: So delegitimizing facts and inflating them into political ideology that automatically has built into it an enemy.

CS: Exactly. And one that is grounded in both attempting to create and perpetuate a sense of fear, and also, one that rejects and ignores and erases the very things that created what, again, the contemporary landscape of inequality today. So one of the places that I go, and maybe we’ll talk about this later in the book, is Blandford Cemetery, which is one of the largest Confederate cemeteries in the country. And I go there and spend the day with the sons of Confederate veterans, so these sort of Neo-Confederates and Confederate Reenactors. And what became clear to me in my conversations with these people is that for them, history is not a matter of fact. It is not a matter of what can be proved empirically. It is not a matter of primary source evidence. It’s a story. It’s a story that they have been told. It is a story that they tell. It is an heirloom. It is a eulogy. It is something that allows them to situate themselves and their family and their family’s history in a way that gives them a sense of value, purpose, and understanding of who they are and who they want to be.

CS: And for many of these folks, no amount of evidence that you present to them is going to change their mind because the way that they move through the world, it’s not based on evidence. It’s based on something that’s much more deeply emotionally embedded into how they understand themselves as part of this larger and longer lineage. And that was really clarifying for me, and it helped me understand that for some people… I think there are many people in this country who just don’t know, there’s a lot of information, and I include myself in that for such a long time. There’s so much about the history of this country that we’re just never made aware of in school. And I believe that when folks are presented with that information, it has the potential to have a transformative impact on how they understand the world and hopefully, move through the world. And there are other groups of people who are operating in epistemologically different universe in which the notions of truth and fact just don’t… There’s no Venn Diagram.

BB: No, there’s no overlap.

CS: And we see it reflected today.

BB: Yeah, for sure.

CS: I’ve been thinking a lot about the relationship between the Lost Cause of the late 19th century and the big lie that we see now, and how people will tell us that this thing that we witnessed on January sixth wasn’t what we saw. We watched it. We know what happened. We know what people said. And it’s the same thing that the Confederacy did at the end of the Civil War. They fought an entire war and seceded from this country because they thought that after the election of 1860, Abraham Lincoln would take away their enslaved workers. And so they seceded in 1861, beginning with South Carolina, and then these states left.

CS: And then after the war, somebody like Alexander Stephens who, again, in his Cornerstone Speech said that the reason they were seceding and creating a new country was because they wanted to continue having enslaved people work for them. Then after the war, was like, “I never said that. What are you talking about?” And everybody is like, “What are you talking about? We heard you say it.” And he’s like, “No, no, no. You must be mistaken. I never said anything like that.” And it’s deeply unsettling how similar what we’re seeing today is to what was transpiring in that way in the late 19th century after the war.

BB: Same playbook.

CS: Yeah.

BB: Really same playbook. Technological advances, and we’re seeing TV and… But same playbook. I’ve got to tell you, there’s some built-in crazy-making to it because you watch things unfold in real-time, and then you’re just… It’s hard. For people listening, so they don’t think this is your phrase, but can you explain real quick what the Lost Cause is?

CS: So the Lost Cause is a movement in which, following the end of the Civil War, the Daughters of the Confederacy, which is an organization of women who were the sisters, daughters, wives of men who fought in the Confederate Army began an attempt to sort of rewrite the history of what happened. And so part of some of the central tenets of the Lost Cause are that the war was not actually about slavery. Even though the war wasn’t about slavery, that slavery itself wasn’t even that bad in the first place, and that it was, in the words of John Calhoun of… A Senator from South Carolina and someone who was a Vice President of this country at one point, that it was a positive good for both Black and white people, something that was perpetuated by a historian named Ulrich B. Phillips, who sort of led the charge that slavery was a civilizing institution, which people don’t realize the sort of predominant narrative of slavery until the Civil Rights Movement.

BB: Oh, my God!

CS: That is, the Dunning School of Reconstruction, which says that formerly enslaved people were too lazy and too inept to be a part of the infrastructure of our political system. And then the sort of Ulrich Phillip school of the historians who said that part of the reason that Black people were experiencing so many of the problems that they were in the early 20th century wasn’t because of all the things that white terrorism and state-sanctioned violence were doing to Black people, but is instead because they were in a better position and more well taken care of when they were enslaved. And then also, what the Daughters of the Confederacy do are put up these statues across the country, many of which were put up, as you can tell, in my own hometown in New Orleans that tell a story about these people who fought for the Confederacy that is meant to honor them, rather than hold them accountable or recognize that they were the people who fought a war to keep my ancestors enslaved. And so the Lost Cause is that idea, that the Confederacy was fighting for states’ rights, that the people who fought in this war were honorable, good men. That slavery wasn’t even that bad. And even if it was, it wasn’t the reason the war was fought.

BB: It took me to this moment in my research, I kept thinking… I think you were having a conversation. Was this one of the reenactor people, Jeff? Do you remember the conversation with Jeff?

CS: I do, yeah.

BB: And there’s this moment where, correct me if I’m wrong, but I’m remembering he was definitely saying that we didn’t understand the Confederacy, that the Confederacy was really about devolution of states’ rights, it was really about states having more control, lesser control of the Federal government, it wasn’t about the enslavement of people. But then he’s going on and going on and you’re transcribing this conversation, but then he slips in a sentence that, as someone who studies emotion, it just grabbed me by the throat because he slipped in a sentence that said something like, “Because if that were true, what my grandparents and great-grandparents and great-great-grandparents fought for and believed in would make them monsters.” Do you remember that line?

CS: Yeah, that was Greg Stewart at the end of the chapter. Jeff said a lot of things similar. That was someone different, yeah.

BB: Yeah, and I thought, “Wow! It’s not this non-empirically primary-source information history. These are narratives about a sense of place and belonging that are just not rooted in fact.”

CS: Yeah, that was telling. That quote’s actually from reporting that was on the New York Times that I put in conversation with some of the things that folks I was meeting were saying. And again, he’s like, “You’re asking me to accept that my great-great-grandfather was a monster.”

BB: Yeah, yeah, yeah.

CS: And to your point, it was really telling. And for me, a moment like that is… I mean personally, I’m not actually interested in whether you think of your great-great-grandfather as a monster or not. I’m not interested in the interiority of your grandfather’s psyche or emotional disposition or even… But I am interested in someone accepting that their great-great-grandfather fought for a monstrous cause.

BB: God!

CS: And I think there’s a profound difference that gets conflated, oftentimes, when we have these conversations. And that’s why I think scholarship today is thinking about racism not as this thing that is in people’s hearts. It’s like, “This person doesn’t have a racist bone in their body,” or, “They’re not racist in their hearts.” And one, I don’t even know what that means. I don’t know why we’re making racism tied to the physiology of one’s body. But it matters a lot what action someone takes that either push back against or perpetuate a system that enacts violence and oppression against people. Obviously, slavery is an enormous… Fighting for the Confederacy and fighting a war that began because these states seceded because they didn’t want their human chattel taken from them, that has to be reckoned with.

CS: And also, you don’t have to accept that as defining you. That’s the other thing that I would want to tell them. And some of the conversations that I think need to be had in that community, it’s like, “You are not defined by the decisions that your great-great-grandfather made.” What would it look like to say, “My great-great-grandfather fought in this war for a cause that runs counter to everything that I believe in today. And my family is not defined by that, my children are not defined by that, my grandchildren are not defined by that.” And it became so clear, too, because Jeff, there was a moment where Jeff talked about how, when he walks through the cemetery, he likes to just come there sometimes and sit as the sun is setting in the gazebo and watch the deer sort of scamper through the tombstones and across the cemetery, and how he likes to bring his granddaughters with him and walk with them through the cemetery and tell them about their ancestors. And so for me, it was clear that this is something that is deeply, again, emotionally embedded in how Jeff understands who he is in the world.

BB: Totally. Totally.

CS: And thus, you see it in real-time, reflective of how he’s going to tell the story of his family, and thus, the story of this country, to his granddaughters, who will then be carrying themselves a certain story of this country that is not reflective of what happened. And how much more powerful would it be if Jeff took them to the cemetery, and instead of eulogizing these people who fought this war to perpetuate human bondage, to say, “Your ancestors did this thing and fought this war, and they were wrong. And they were wrong to do it, and the cause was wrong.” How freeing might that be to those little girls? How freeing would it be, not only in that moment, but also, to say that you are not defined by the decisions that the people who have come before you have made, whether it be your family or otherwise. Because if you can’t say that honestly about your own family, how are you going to say it about this country?

BB: You cannot.

CS: You can’t.

BB: And imagine the power. And we’re talking about a cemetery where a lot of Confederate soldiers are buried, right?

CS: Thirty thousand.

BB: Thirty thousand. So just to give people a sense of place. To look at your granddaughters in that gazebo and to say what you said and to say, “And the reason why we don’t support what they fought for is because in our family, we believe in love and justice and equality. And we don’t feel shame because they weren’t the decisions that we made, but we do feel a responsibility of accountability, of getting the story and the history right so it’s not repeated.”

CS: Exactly.

BB: “And that’s why I brought you here.” But I have to tell you that the writing’s on the wall about what happens when those… Maybe, maybe not, because a lot of us were raised by parents who tried those narratives and we chose different ones, but you can see how, then, the granddaughters start to use your verb, which is so perfect, “conflate,” their love for their grandfather with an ideology and an unwillingness to reject an ideology that feels like is rejecting him.

CS: Exactly.

BB: God! I mean jeez! Okay. Oh, I have to say that I had to wrestle with some shame when I was reading this. Not general white shame, but shame about thinking I’m an educated person in terms of history. And let’s talk about Angola. I lived in New Orleans for six years, growing up. And so I even knew the name Angola. What does Angola mean if you’re from New Orleans?

CS: What does Angola prison mean? Angola, you are, in many ways, inundated with this message that it is a violent place. I think all the time about… This didn’t make it into the book. We had to cut it because the space. I have a document of 40,000-50,000 words that just didn’t make it into the book.

BB: Yeah.

CS: Maybe there’ll be something else one day. But when Hurricane Katrina was happening, Ray Nagin was the mayor. And there were these conversations that were happening about people who were looting or stealing. And we can get into the entire framework of what constitutes as looting in the midst of an unprecedented natural disaster, and who is looting and who is foraging, and these are conversations that have happened. But Ray Nagin, mayor of New Orleans, who was Black, said… I think it was a press conference, at some point. I believe he said it like, “If you’re looting or if we catch you looting or catch you doing something you’re not supposed to do, we’re going to arrest you and send you straight to Angola, and God help you when you get there.” To me, that statement…

BB: Whoa! I have goosebumps!

CS: It embodies the sort of way that I was taught about Angola, growing up, and the messages I heard about this violent place for these terrible people, where they put you away and throw away the key so that none of us have to ever worry about you again. And that was the message implicitly and explicitly that I got about Angola, growing up. And part of why I wanted to go back there was to sort of push back against my own… To unlearn so much of what I had learned about that place, growing up.

[music]

BB: So there are a couple parts of the book where I just had to put it down. I was almost too tired to even throw it across the room, which I can do, sometimes, when I’m really pissed off or just feel overwhelmed. One of them was the gift shop at Angola.

CS: Yeah.

BB: And the, I don’t know if it was a 20-foot long photograph? So when you go to Angola and… I just want to keep saying, I have to watch myself, and I made a note on my piece of paper as we’re doing this, “Stop saying when we went to Angola because you didn’t really go with Clint to Angola,” but I felt like I went with you because of this book. But when you take us into Angola, there’s two things I want to talk about: This gift shop and this photograph. And I did not understand at all the history of convict leasing. Jesus Christ!

CS: So for context, Angola, for those who aren’t familiar, is the largest maximum security prison in the country. It is 18,000 acres wide, bigger than the island of Manhattan. It is a place where 75% of the people held there are Black men, over 70% of them are serving life sentences, and it is built on top of a former plantation. What I tell people is that if you were to go to Germany and you had the largest maximum security prison in Germany that was built on top of a former concentration camp, in which the vast majority of the people held there were Jewish, that place would be a global emblem of anti-Semitism. It would be so abhorrent and so disgusting. You can’t even conceptualize it.

BB: You cannot.

CS: Because our sensibilities, we would never allow a place like that to exist, and rightfully so. It would be morally abhorrent in ways that we almost don’t even have the language for.

BB: That’s right.

CS: And yet, here in the United States, we have the largest maximum security prison in the country, in which the vast majority of people held there are Black men serving life sentences who go out into fields and work for virtually no pay on land that used to be a plantation while someone watches them on horseback with a gun over their shoulder. And that place exists on American soil in the State of Louisiana. And part of what I’m thinking about when I go to Angola is: “What are the ways that white supremacy, not only enacts physical violence against people’s bodies, but also collectively numbs us to certain types of violences that, in another global context, would be wildly unacceptable? How does that place exist at all, much less on that land?” And to your point, “What does it mean that that place not only exists, but has little to no interest in honestly talking about its relationship to the history of the land that it falls on?”

CS: I was on this tour, and the word “slavery” didn’t come up at all, until I asked a question about it. I’m in this museum, even saying it… The fact that the place is an active prison, the largest prison in the country, and has a museum, a museum that doesn’t mention slavery, and in that museum is a gift shop, where there is a mug on which says… There’s a silhouette of the front gate of Angola, and you see the silhouette of a body of someone who’s standing there with a gun. And on the coffee mug, above and below that silhouette, it says, “Angola: A gated community.” To make a mockery of the conditions that thousands of people in that prison are living in, that prison that used to be a plantation; to go into the gift shop and see a 20-foot long painting or photograph of a group of Black men walking into the fields of that place with garden hoes over their shoulder while someone, again, is on horseback with a gun watching over them as they go out into the fields.

CS: I mean the thing about Angola is, again, it’s not even that they didn’t talk about it. It’s that it felt like in every part of that place, there was a profound indifference to what the history of that place was. And not only the history of that place, but to what the actual conditions people were living in at that moment were. How do you put a gated community like it’s a joke on a coffee mug that you sell in the gift shop outside of a place where the average sentence is 83 years, but the vast majority of people are going to die in that prison? Some of them for things that they did as children. Some of them convicted by non-unanimous juries.

Speaker 4 (CS’s son): You forgot your popcorn. You forgot your popcorn.

CS: I forgot my popcorn?

S4: Yeah.

BB: Hi!

CS: Do you want to say… Do you want to say hello? This is my friend, Mrs. Brené.

BB: Howdy!

S4: Who’s Ms. Brené?

CS: Say, “Hi, Miss Brené.”

S4: Hi, Miss Brené.

BB: Hi, I’m talking to your dad about his amazing book. How are you?

[chuckle]

CS: You’re doing well?

BB: How old are you?

S4: Three, but I’m turning four.

CS: Three, but turning four.

BB: Three, but turning four.

CS: Very soon.

BB: Did you know your dad wrote a book?

S4: Mm-hmm.

BB: It’s really good. You’re going to be four soon!

S4: Mm-hmm.

CS: What are you going to do for your birthday party?

S4: Play games.

BB: What kind of games?

S4: Foamnasium games.

CS: Foamnasium.

BB: Foamnasium! That sounds really fun!

CS: What is the theme of your birthday party? What kind of party are you going to have?

S4: Dinosaur!

BB: Okay, wait a minute. Dinosaurs?

S4: Uh, yeah.

BB: What is your favorite dinosaur?

S4: Now, it’s the Apatosaurus.

CS: The Apatosaurus.

BB: Oh, the Apatosaurus. Is the Apatosaurus a vegetarian or a meat-eater?

S4: It eats only plants.

CS: Only plants. So what does that make it? A carnivore or an herbivore?

S4: An herbivore.

BB: Herbivore. What about a T-Rex? Herbivore or carnivore?

S4: Carnivore.

BB: Okay, I’ve got a question, this is a big question in my family. Velociraptor. Carnivore or herbivore? Which one? The Velociraptor.

CS: Is the Velociraptor a carnivore or an herbivore?

S4: Carnivore.

BB: Is it really?

CS: I think so.

BB: What about a Triceratops? The Triceratops is my favorite.

S4: It eats only plants.

BB: It’s a vegetarian?

S4: Mm-hmm.

BB: That’s why it’s my favorite.

CS: Alright. Do you want to say, “Thank you Ms. Brené”?

S4: Thank you, Ms. Brené.

BB: Thank you. And you know what? Happy early birthday to you.

CS: Say thank you.

S4: Thank you.

BB: I hope you have a great party.

[chuckle]

S4: Not today.

[chuckle]

BB: Not today.

[chuckle]

CS: Not today. Alright, let’s go get you a snack. Hold on.

[chuckle]

BB: Okay, that was the best podcast moment of my podcast career.

[chuckle]

CS: I’m sorry about the interruption.

BB: What’s his favorite dinosaur?

CS: The Apatosaurus.

BB: The Apatosaurus.

CS: Yeah.

BB: Okay, wow!

CS: One of the long-necks.

BB: Like the ones that we used to call…

CS: The Brontosaurus.

BB: Brontosaurus.

CS: Which it existed, and then they were like, “No, it didn’t exist.” But I think recently, they said it actually did exist. It’s very confusing, this world of dinosaurs.

BB: Yes.

CS: And it’s like, “Is it real? Is it not?” And there are more long-necks than I ever knew. The Argentinosaurus, which apparently, was the largest dinosaur of all time. I’ve learned more about dinosaurs this past quarantine than I ever thought I would know.

BB: When Charlie was his age, I knew more about excavators and backhoes and construction equipment than one could ever need to know.

CS: There you go.

BB: Okay. Tell me about the bus ride leaving Angola with Mr. Norris Henderson.

CS: So Norris Henderson, remarkable man and political activist who does such important work in New Orleans and across the state. He was incarcerated for 30 years in Angola, and got out in 2003. And I went with him on this trip, and I was sitting next to him on the bus. And we were having conversations about everything that we were experiencing on the trip. And as we were leaving Angola at the end of our visit, there was a moment where, as we were leaving, in the distance, you could see men sort of lifting up their garden hoes and lifting up their shovels and ploughing them into the ground, and watching as a warden watched over them on horseback.

CS: And Norris, he sort of held his hands up so that you could see his palms, and he was rubbing his palms with the thumb of his other hand, and was talking about the calluses that had formed on his hand after all those years of working in those fields. And what it felt like for him, emotionally and psychologically, to work, to pick cotton for seven cents an hour in fields that, as he put it, where his ancestors could have very well been enslaved. And it clearly impacted him in a profound way. And I was watching Norris and listening to Norris. And I look back at those men who were becoming distant silhouettes of themselves as we left the prison, and I was just like, “How does this happen? How do we do this to other human beings? What an indictment of our country’s understanding of itself, or perhaps, more accurately, its inability to understand itself.”

BB: Yeah.

CS: “That we would allow these Black men, over generations now, to work on this land and to pick crops and cotton on land that had once been a plantation?” In all of the places that I go, I’m spending time with someone who has a direct relationship to that place. And I think that chapter wouldn’t be what it was without Norris providing the perspective of both someone who has an acute understanding of the history that makes a place like that possible, but also, someone who experienced it directly and has, through his mind and in his body, experienced the repercussions of this country’s failure to see itself for what it is and for what it’s done.

BB: The question that you asked in the beginning of this piece of the conversation on Angola, when you compared it to a prison built over a concentration camp in Germany that housed 70% Jewish people, like you said, we don’t have a word. It’s just so far outside of what would be considered okay across the political spectrum. It would just never be okay. And so the word that keeps coming up for me is just “dehumanization, dehumanization, dehumanization”. Can I read something to you from your book?

CS: Please.

BB: It was a small moment that just captured it so beautifully to me. You write, “The first thing I saw inside the museum was the wall behind the checkout counter. On the wall was a 20-foot wide image that kept my feet in place. Below the words, Louisiana State Penitentiary, was a photograph of two dozen Black men being marched into fields, each of them carrying a long black hoe. They were wearing an assortment of gray sweatshirts and white T-shirts that rendered their bodies almost indistinguishable. To their far right was a white woman on horseback, her long, blonde ponytail extending from beneath her black cap and down her back. The sun, full and luminous even in the black and white image, hung just above the trees in the distance, suggesting that these men were beginning their day.”

BB: “The procession of Black skin carrying black hoes into this field further erased the identities of each man. They existed in this photo not as individual people but as a homogenous, interchangeable mass of bodies. I turned away and then looked back multiple times to make sure I understood what I was seeing. The photo seemed to have been taken recently, it was not a vestige of the past. It was, indeed, a white person on horseback herding a group of what seemed to be exclusively Black men into a field where they were forced to work. The unsettling nature and placement of the image was compounded by the fact that it welcomed its viewers into a gift shop, stockpiled with an extensive inventory brandishing the Angola name.”

BB: There’s two things that I want to understand about this. One is a question that’s a moral question, a question about moral courage, and the next one is a policy question. The first question I have for you, and I’m not expecting anyone to help me understand how morally and ethically it’s okay that they’re selling shot glasses in a museum where people are probably being killed and dehumanized every… For sure, dehumanized, but probably killed on a regular basis. “What do you think we have to tell ourselves as Americans, as white people in the United States, what is it that we’re telling ourselves? What’s the narrative that makes this okay?”

CS: I think with a place like Angola, it’s a confluence of things. It is both a failure to understand the history of slavery, to understand the landscape upon which it took place, to understand how recent this was. I think all the time about how my grandfather’s grandfather was enslaved, that the woman who opened the National Museum of African-American History and Culture with the Obama family in 2015, who rang the bell that sort of signaled that this museum that was generations in the making was opening, that she was the daughter of an enslaved person. Not the granddaughter, not the great-grand daughter, but the daughter, her father had been born into slavery.

BB: Right, right. Right.

CS: And so this history that we tell ourselves was a long time ago wasn’t, in fact, that long ago at all. We had slavery in this country, in the British American colonies, that would become the United States for 250 years. We’ve only not had it for about 150. It existed in this country for a century longer than it didn’t.

BB: Right.

CS: And so the idea that that institution, that centuries-long institution would have nothing to do with what our current landscape of inequality looks like, with what our current society looks like, is both morally and intellectually disingenuous. It is embedded into every part of our economic, social, and political infrastructure in ways that are clear and in ways that are far more subtle. So I think that there is a failure to understand, one, how recent this history was and how deeply it continues to impact every part of our society today.

CS: And then in the specific context of prison, it is reflective of what scholars and activists have been talking about for many years now, especially in the midst of the Black Lives Matter movement, that part of the purpose of a prison is to render the people in that prison as sort of abstractions, as political and social abstractions, rather than human beings who are mothers and fathers and brothers and sisters and sons and daughters, who are loved and who do love people in this world. And if you only understand someone as an abstraction or as a caricature of themselves, then you allow things to be done to those people because you don’t see them as people.

BB: Yeah.

CS: Because you see and understand them as bogeymen, or you see and understand them, to go back to the beginning of our conversation, as people who deserve what has come to them because of decisions that they have made, that they are singularly responsible for.

BB: Moral exceptions.

CS: Right, rather than seeing them as largely having been born into a set of conditions, that had any of us been born into, our lives would have very possibly ended up on a similar trajectory, entangling us in the criminal legal system. So I think it is a sort of collective ahistoricism that so many in this country carry. I think it is the success of the social function of what prisons are meant to do, which is to render people invisible, or to render them caricatures of themselves. And I think when you bring those two things together, you get a place like Angola.

BB: Yeah.

CS: You get a place where there’s a prison on top of a former plantation with coffee mugs and shot glasses being sold on land that continues to have people on death row.

BB: So for me, all of the variables that you’re bringing together and the confluence of those variables. So you’ve got: We don’t understand history. To make us more comfortable, we’ve pushed it away. I always have to remind myself that my mom is older than Ruby Bridges. It’s like this is yesterday, people.

CS: Yeah, it’s so important.

BB: Yeah. And so the lack of historical understanding, the successful dehumanization of an entire group of people, based on their situation that any of us could be in, had the context been right, and then there’s a policy reason. I know we’ve gone long, but if you could just take a few minutes…

CS: I have plenty of time.

BB: If you could just walk us through convict leasing. I don’t think people understand this. And it is so horrifying because it really feels to me like… It’s a question that Laura and I both had after we finished reading your book. We were both like, “Jesus! Prisons are like the new plantations.” What is convict leasing?

CS: So following the end of the Civil War, following the abolition of slavery, as many will know, or perhaps not. But the 13th Amendment abolished slavery, with the exception of those who are imprisoned. So involuntary servitude is unconstitutional, with the exception of those who have been convicted of a crime. And so what happened after the end of the Civil War is that throughout the south, you had Black people who were looking for work, who were trying to find their families, who were moving from different parts of Louisiana from one city to another, looking for the people that they love or looking for new opportunities. And sometimes, moving across states. People’s families were sold from Virginia to South Carolina to Georgia to Louisiana to Texas. And so you have Black people moving, physically moving in a way that this country had not seen before.

CS: And in order to, one, regulate the bodily autonomy of formerly enslaved people, and two, in order to find a way to get the resources, the human resources and labor that one needs in order to continue to work on and cultivate land that, only just a few years ago, had been cultivated by enslaved people, the southern states created a series of laws and Black codes that, essentially, criminalized actions that, in no other context, would be understood as criminal. So like a vagrancy law, is this idea that if somebody caught you walking around down the street, and you didn’t have a letter or a note from your employer or showing that you were employed, even if you were looking for work, even if that is the reason you were walking, then you would be arrested by the state, and you would be then sold to a person or a company where you worked in what scholars would call sort of neoslavery, or as Douglas Blackmon calls, Slavery by Another Name, in which you were contracted to these different places and you worked on the same land that you had ostensibly been emancipated from only a few years before.

CS: And in some ways, the scholars argue that it is… It was, in some ways and in some context, more dangerous because… And again, this is being said with the caveat that slavery was experienced in many different ways, in many different contexts. But it was not uncommon for formerly enslaved people to be treated more poorly as contracted convicts than they were as enslaved people. Because if you’re an enslaved person, somebody has made an investment, a financial investment in you and also, in your children or in the potential of you to have children. So there’s the deeper financial commitment to that person. Whereas, with convict leasing, if you go back to some of these records, the way that some of these folks who were running this land, there was no reason for them to not work this person to death because they were like, “We’ll just get another one.” If they got these people for so cheap to work on this land, there was no reason for them to want to feed them well, to house them well, to give them time off. They were like, “I’m renting this person, and if this person dies… ”

BB: People are replaceable.

CS: “And I will get a different one when that person keels over and dies.” And so that is what convict leasing is. And so I always want to be mindful because sometimes, I think people hear something like that, and they hear and see and observe our contemporary landscape of mass incarceration, and they’re like, “Well, prisons are the new plantations,” or, “Mass incarceration,” more specifically, “Mass incarceration is the new slavery.”

BB: Yes, yes.

CS: I am of the belief… I take after the scholar, Saidiya Hartman, who talks about the afterlife of slavery, and this idea that slavery and mass incarceration are phenomenologically distinct entities. They are separate and can and should be interrogated and excavated on their own cruel, inhumane merits. And we don’t need to say that one is the other in order to legitimize or amplify or magnify the horror of what contemporary prisons do. But what is absolutely true is that the remnants of enslavement shape what our prisons look like in profound ways. The residue of that system, which again, was not that long ago. Convict leasing was not happening that long ago. And in some states, not that long ago at all. It is absolutely true that prisons look the way that they do, that a place like Angola looks the way that it does today very clearly because of the history of slavery.

CS: And so I think it’s always important for us to be precise because sometimes, people can make a statement that says one thing is the other, but to my mind that can sometimes undermine the very argument that we are making about the horror or barbaric nature of the places that we’re trying to analyze. So slavery and prisons, contemporary prisons have the marrow of slavery in them in ways that all you have to do is look and see. And it is also its own unique sort of horror, that that should be interrogated on its own horrific merits just for the sake of that.

BB: Okay, so that’s so helpful for me to understand because I do think we want to slip into the, “Is this the new this?” Or, “Is this current-day this?” Or, “Is this neo this?” Tell me about, just so I can understand because I’m really invested and interested. Help me understand the importance of understanding the history and the connective tissue between the current industrial prison complex and slavery. And help me understand the importance of understanding the historical connections and the marrow. But why is the interrogation of these two things doing that separately so important? That’s what I’m hearing you say. Because I really want to understand because I think there’s something there that’s important.

CS: Just practically, the institution of slavery in the Americas was a system in which human beings were rendered chattel, and in which you were held in bondage. You were the property of another person. And by the nature of the institution, your child would also be property of that person, and their child would also be property of that person, so on and so forth until the institution was over, or until you were sold to another person.

BB: Okay, right.

CS: That is not what prisons are.

BB: Right.

CS: If you are incarcerated, it does not mean that that prison gets to incarcerate your child. It is clear that there is a relationship between how likely someone is to end up in prison or entangled in the criminal legal system and how… And whether or not their own parents were. We know that. That is something that scholars and sociologists have been exploring for many years.

BB: Right.

CS: But that is a profound difference.

BB: Yes, huge.

CS: So I think that the idea of intergenerational chattel bondage is something that is unique and deserves its own… We should take it and set it over here.

BB: Yes.

CS: And say, “Look at this unfathomable, horrible thing.” And then we should take prisons and mass incarceration, we should put it over here, and we should say, “Look at this terrible, horrible thing that is terrible and horrible, but is not the same as that.” Certainly, parts of slavery have shaped parts of our prisons, and again, in profound ways. But I think if we say that prisons are the new slavery or prisons are slavery, then we are doing a disservice to the people who actually experienced slavery.

BB: Yes.

CS: And doing a disservice to the people who live in prison.

BB: Yes.

CS: Which have its own unique horrors that are not like anything else in the world.

BB: That’s so helpful.

CS: I just think the precision in our language is important.

BB: Yes.

CS: And I understand and very much sympathize and empathize with the desire to use those sort of parallels and comparisons in order to bring attention to the horrors and realities of something. But I just tend to believe that we can do that without saying a thing is another thing when it’s not.

BB: Yes. And thank you for that really important, for me, teaching moment because it’s easy to slip into those things and it’s an outraged slippage, sometimes. But it actually, in some ways, is potentially profoundly diminishing of experiences that are built on diminishment.

CS: Right.

BB: So I really appreciated you separating those things out because I’ve heard that many times, especially as we go in the new discourse right now.

CS: Right.

BB: So let me just say, if you’re listening right now and you’re like me and you’re just blown away by the teaching moment that just happened, I feel like every page is that in How the Word Is Passed. It is one of the most important books I’ve read in my life.

CS: That means so much.

BB: Yeah. And I’m so grateful for not just your scholarship. Do I call you Clint or Dr. Smith?

CS: Clint. Definitely Clint.

BB: Clint. Not only your scholarship, but your heart because both are on display in equal amounts in this book. And that’s rare.

CS: Thank you so much.

BB: Yeah, that’s rare. Alright, can we go into some rapid fire questions?

CS: Let’s do it. I love rapid fire.

BB: You do?

CS: Well, we’ll find out. [chuckle]

BB: Yeah, we’ll find out, okay. Yeah, because you know, one of the reasons why I ask these questions, and some of them are fun, because I have a lot of serious conversations on this podcast with a lot of people who are teaching us hard things, but I just want people to know you. You’re a beautiful man. I just want people to know you as a person, too. Alright, fill in the blank for me. Vulnerability is?

CS: One of the most important things we can teach our children.

BB: Oh! You, Clint, are called to be very brave, but your fear is real. You can feel it in your throat. What is the very first thing you do?

CS: I take a deep breath, and I think of all of the people who came before me, who did brave things, who did unimaginable things, even when they didn’t know if they would see the fruits of their labor, or of their effort, but who did it anyway. And who did it because it would help somebody and build a better world for somebody who they might never meet.

BB: What is that saying? Brave are those who plant the trees, whose shade they’ll never enjoy?

CS: Mm-hmm.

BB: Okay, what is something that people often get wrong about you?

CS: I think people think I’m older than I am. I think maybe the bald head throws people off. But yeah, I’m 32. And I think, sometimes, people are like, “You’re not 45?” I don’t know. What’s something somebody gets wrong? I love, shoutout to boy bands of the ’90s like NSYNC, that was my jam. And when my kids came out of the womb, we were singing Bye, Bye, Bye. So that’s a big NSYNC fan.

BB: You’ve already mentioned Bell Biv DeVoe, so we’re in so much trouble already, okay.

CS: Oh, man!

BB: Alright, the last TV show that you binged and loved?

CS: Can it be one that I’m currently binging?

BB: Yes.

CS: My wife and I are watching Pose, which is just… I can’t remember the last time I was so invested and rooting for characters. And we’re only on season one, we’ve finished season one, and we were audibly gasping, and then cheering, and standing on the couch at various points during the episode. That show was so important because, obviously, because it centers the lives of transgender people in a way that I’ve not seen before on television. But it is just so human. It is so human. And as my wife, Ariel, would say, “It is about human relationships and living in community,” which is why we’re here. Ultimately, we are here because we are trying to make meaning of our lives through the relationships that we have with people. And that show demonstrates it in such an amazing, beautiful, beautiful way. I really, really enjoy that show.

BB: Yeah, talk about vulnerability. There’s a lot of vulnerability on that show.

CS: A lot.

BB: Yeah.

CS: So much, yeah.

BB: Favorite movie?