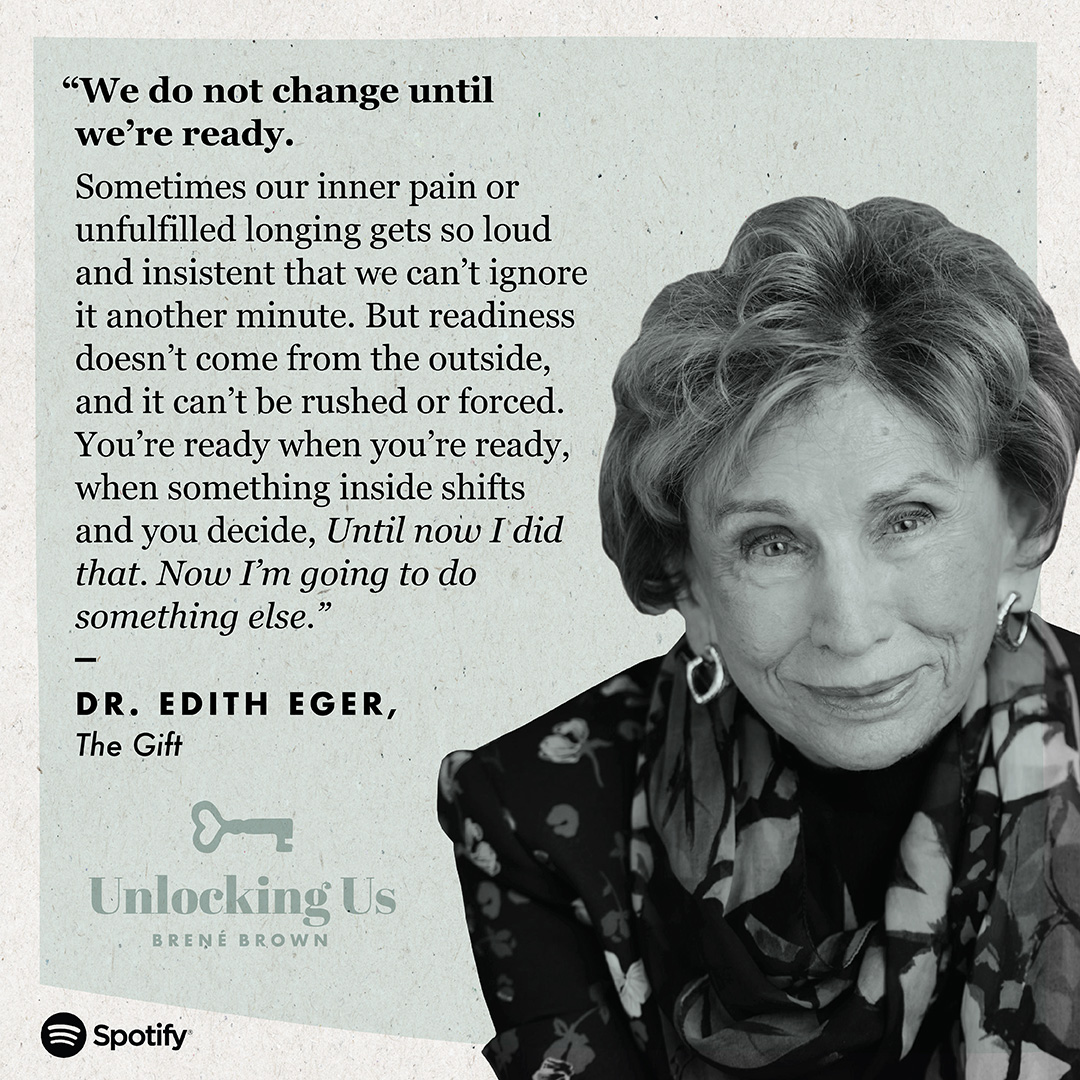

Brené Brown: Hi everyone. I’m Brené Brown and this is Unlocking Us. This week, I am talking with Dr. Edith Eger about recognizing the choices we have in our lives that sometimes don’t appear or feel like choices, and also understanding and identifying some of the gifts in our lives that I can tell you for sure don’t always feel like gifts in the moment. Dr. Edith Eger is a clinical psychologist. Her books, The Choice and The Gift are the focus of our conversation. She is a Holocaust survivor who’s dedicated her career to helping us understand trauma, anger, rage, resilience, and the power of getting to choose how we see ourselves, and the importance of resisting the labels that people put on us. This was a once-in-a-lifetime experience for me to talk to Dr. Eger, and I’m so grateful that you’re here to be a part of it.

BB: Dr. Edith Eger is a sought-after clinical psychologist and lecturer. She works to help individuals overcome limitations, discover their powers of self-renewal and achieve the things they’ve previously thought unattainable. Using her own past as a Holocaust survivor and thriver as a powerful analogy, she inspires people to tap into their full potential and shape their very best destinies.

BB: Her first book, The Choice, became a New York Times bestseller, beloved by Oprah and thousands and thousands of readers, and it details her experience as a Holocaust survivor and invites readers to join her in moving from recovery to discovery and beyond. In her most recently released book, The Gift: 12 Lessons to Save Your Life, Dr. Eger offers a hands-on practical guide that encourages readers to change the thoughts and the behaviors that often keep us imprisoned in the past.

BB: Before we jump into the podcast, I want to share a little bit more context about Dr. Eger, in case you don’t know her, or you’re not familiar with her work or her stories. In the Choice, she talks about how she and her family were sent to Auschwitz at the age of 16. Her parents were both killed the day they arrived, and she and her sister faced unimaginable trauma and terror there. She was liberated in 1945. She then came to the United States and spent decades, as you can imagine, struggling with flashbacks and just serious post-traumatic stress. She really fought — it is the only word I can think of — her way back to a life where not only did she start to understand her own trauma, but she started to teach us about it.

BB: Both The Choice and The Gift are about her story and her work. They’re about healing and they’re about how we can be imprisoned sometimes in our own minds, after we’re actually set free in some ways. These are difficult stories and stories about courage and stories about leaning into the truth of our lives and owning it so that we can write new stories. Welcome Dr. Eger.

BB: Hi, Dr. Eger. I can’t even tell you how, in preparing for this and reading your work, how useful you’ve already been. You can’t read your work and be unchanged.

Edith Eger: Oh my god.

BB: That’s not a possibility. That’s not in the consideration set. So, tell me what led you to write your story and share your insights and wisdom and knowledge with us in The Choice.

EE: Well, you know for many years people asked me to write my book, and I would say, “I have nothing to say.” And then Philip Zimbardo was telling me, “You know, Edie, I’m very serious because the people who survived are famous are all men and we need a female voice. That did it.” So, The Choice is really the female voice of Viktor Frankl, but I’m not Viktor Frankl. He was an MD, he was 30-some years old in Auschwitz. I was a 16-year-old in love and my boyfriend told me I have beautiful eyes and beautiful hands. And I said to myself, “If I survive today then tomorrow, tomorrow I’ll be free.” I remember that tomorrow was very important because I was told every day that I’m sub-human and I’m cancer to society, and I’m never going to get out of here alive. I will… Only way get out of here as a corpse, and I’m here telling you how not to allow the external or whatever who tells you, because you have your inner strength and look at life from inside out. So, I call Auschwitz an opportunity like everything else in life, everything, everything has to do with the fact that the way we think. that’s what we create.

BB: You don’t call yourself a therapist but a guide.

EE: Yeah.

BB: In fact, you write that your goal is to help all of us identify our mental prisons and develop the tools we need to become free, and you believe the foundation of freedom is the power to choose.

EE: Yeah, how beautifully said. I think the more choices we have, the less you feel like a victim. I refuse to say I’m a victim because it’s not my identity. It’s not who I am. It’s what was done to me. That just comes to me that, in a way, we are all victims of victims.

BB: Say more.

EE: That’s why we blame… You’re still like children, because children blame. Why do you blame? You’re still a child. You don’t take responsibility. There is no freedom without responsibility. It’s anarchy. So many times, I ask people, “Would you like to be a baby or a big girl, or a baby and a big boy, because while you’re a baby, you’re sitting in a back seat of the car. You can mess around and do anything because someone is driving. So, do you want to be a driver? Or do you want to be driven?”

BB: Yeah, and you know what, sometimes we climb in the back seat because we don’t want the responsibility of driving.

EE: Exactly.

BB: But then we’re angry that we’re being driven.

EE: Exactly. It’s a double-edged sword. Yes, the approach-avoidance conflict, that we talk about in psychology, that I want to approach it and I want to avoid it. And yet, growing up is much more fun than being a child because you are child-like. You ask a child, “Why do you do that?” The kid would say, “Because I feel like it.” The kid doesn’t care about consequences. So, I like my Hungarian chocolate cake, but I know I have a very bad scoliosis, and if I gain weight, I have more pain, so I don’t have to run from the chocolate cake. I can look at it and I can decide whether I will reach for it or not, so that’s why I like the idea of, to being child-like at 93 but not childish, to be not smart but to be wise and decide before I say something. But that it’s really very important that I have to say it, I listen more now and guide people to be very compassionate listeners.

BB: You write about this. You say this so lovingly but so firmly in both of your books. You say, “We will all experience trauma and pain and loss.” What about the idea that I am freer from the past, I’m freer from the trauma, if I pretend it doesn’t happen? If I don’t investigate it. If I just go away from it. What about that belief?

EE: Well, it’s called denial, delusion. We use a lot of defense mechanisms to run, to fight the fear, and then we put ourselves in our own concentration camp. You and I are wonderfully fitting each other because you’re a Texas girl.

BB: Yes.

EE: And people are so kind in Texas and I’m Hungarian. And my English is your English, but I say it the same way as… I’m trying to say it the same way, because when I came to America, I just wanted to be you. I wanted to be a Yankee Doodle Dandy and I didn’t want to speak English with an accent. I spent three years at the university trying to get rid of my accent and look, I am what I am, and I went back to Auschwitz and I decided, I’m not Popeye. I’m Edie. And to reclaim that innocence and assign the shame and guilt to the perpetrator, I had to create my own theory that you take my hand, and we revisit the places where you’ve been. But you’re not there. You’re here with me. I provide you the atmosphere because here you can feel any feelings without any fear of being judged.

BB: There’s so much effort and so much struggle, so many years working to lose your accent, to blend in, to forget your past, to lose yourself in what was your new life. Did you experience anti-Semitism, prejudice, anti-immigration sentiments? Did you experience those things here in the US?

EE: I remember I had that boy, 14 years old, in Texas, and he told me that America has to be white again, and he’s going to kill all the Jews, all the N word. I don’t say that. So, I had a choice to either react or respond. There is a difference. If I would have reacted, I would have taken that boy. I would have dragged him in a corner. I would have stepped on him, and I would say, “Who do you think you’re talking to? I saw my mother going to the gas chamber, but I knew that God sends people my way. They don’t come to me. You were sent to me.” I said, “God, what’s the meaning of that?” Then God said, “Find the bigot in you.” And I said, “God, that’s not true at all.” Because I came to America penniless in 1949. I worked in a factory and I went to the bathroom, and one of them said colored.

EE: After Nazi Germany and communist Russia, I was very, very disappointed to see prejudice, which means to pre-judge. I always went to the colored bathroom. I remember the lady came and wanted to explain to me that I have to go to the other bathroom, and I pretended I know nothing, I don’t know what you’re talking about. So, I joined the NAACP; I marched with Martin Luther King in Washington, DC. I just spoke to Facebook today. I don’t know Facebook from podcast. I don’t know any of that. I have a wonderful giant grandson who does all that American stuff, but I had to learn that that little boy gave up all his freedom to David Koresh, a white supremacy organizer. It’s maybe before your time.

BB: I know of it, yes.

EE: You do, you know of it?

BB: Yeah.

EE: Thank you. Anyway, I created that environment and took a deep breath and I looked at that poor boy who gave up his freedom to David Koresh who taught him how to hate and my empathy, not the sympathy, took a hold of me. And I said, “Tell me more.” And that’s what you and I do. We invite people to reclaim their true self. I’m not a victim. I was victimized. It’s not who I am. It’s not my identity. It’s what was done to me.

BB: Let me read something from your book.

EE: I’ll be delighted to listen.

BB: Here’s what you write, “I am here to tell you that the worst prison is not the one the Nazis put me in. The worst prison is the one I built for myself. Although our lives have probably been very different, perhaps you know what I mean? Many of us experienced feeling trapped in our minds, our thoughts and beliefs determine and often limit how we feel, what we do and what we think is possible. In my work, I’ve discovered that while our imprisoning beliefs show up and play out in unique ways, there are some common mental prisons that contribute to suffering. This book is a practical guide to help us identify our mental prisons.” You say, “The foundation of freedom is the power to choose.”

EE: That’s why my name is not shrink. My name is stretch. I stretch your comfort zone, so you move away from the black and white, all or nothing mentality. I think it’s very important to think about your thinking and pay attention on what you’re paying attention to. It’s good to have a goal and then you have a way right away when you get up in the morning, how are you going to spend your day and how you’re going to think before you say anything. And ask yourself — is it really very important? I’m a great grandma now with seven great-grandchildren, and I am thinking before I say anything, whether it’s really loving and kind and the way I want to be known. I want to be the fireplace that the moth wants to come to. And it’s not what I say — it’s who I am.

BB: Yes.

EE: One of a kind. Yes, I say what I lived, everything I tell you, I lived it.

BB: And There’s a story you tell in The Gift. I’ve read Viktor Frankl, who I know was a friend, and a mentor to you…

EE: Mentor yes.

BB: Talk about this. You tell us that the day that you learned the difference between negative and positive freedom was on Liberation Day in May 1945 when you were 17. Here’s what you write, “I was lying on muddy ground in a pile of the dead and dying when the 71st infantry arrived to free the camp. I remember the soldiers’ eyes full of shock, bandanas tied over their faces to block out the stench of rotting flesh. In those first hours of freedom,” this is so amazing, “I watched my fellow former prisoners, those who were capable of walking leave through the prison gates, but moments later they returned…

EE: They came back.

BB: And sat listlessly on the damp grass or on the dirt floors of the barracks, unable to move forward. Viktor Frankl noted the same phenomenon when the Soviet forces liberated Auschwitz. We were no longer in prison but many of us weren’t able physically or mentally to recognize our freedom, we would finally been released from the Nazis, but we weren’t yet free.”

EE: And this is… You see, my life doesn’t start or end in Auschwitz because I started to build transitional living centers for battered wives. And I’ve studied them that they leave, and I worked so hard so they can leave, and then a few weeks later, “I miss you, my darling. I’m never going to do that again.” And she keeps going back, any time, maybe seven… I count it, 7-15 times, they go back because they do the familiar. We have the freedom, physical freedom, but we didn’t know what to do with freedom. Seligman writes about learned helplessness. So, they would go through the gate and then go back and sit down. Freedom is very scary. Freedom without responsibility is anarchy. That’s why I write to write a constitution for the family.

BB: Say more.

EE: So, you have a constitution with the children and the children have to take part of the decision process. So, you are authoritative parent, not authoritarian parent. You’re not a dictator.

BB: Oh, there’s a difference.

EE: You don’t say, “I said so.” If your child said, “Why do I have to do that?” Before, my parents, “Because I said so.” That was no democracy. And the shame that you talk about is amazing, how awful, because I was shamed as a child, because I didn’t say what the teacher wanted to say. And the teacher would walk around with a ruler and put me in a corner, and I was afraid to look up because I was cross-eyed. I felt less than human at an early age. But you know what, maybe God put me there so I can spend a lot of time alone. And my mother told me, “I’m glad you have brains because you have no looks.” My sisters were beautiful, and when I arrived in Auschwitz, I took care of my sister, so everything has a gift in it. Why is The Gift a gift? Because after The Choice people kept calling me, “I need something practical.”

BB: Yeah.

EE: Tell me what to do. Speak English and tell me what to do.” And that’s how The Gift came.

BB: I look at Oprah’s quote on the top of The Choice.

EE: I love her.

BB: “I’ll be forever changed by Dr. Eger’s story. You can’t say it any other way. The person who starts this book, The Choice is not the person who finishes the book. It changes us.”

EE: Thank you.

BB: Then you’ve got The Gift where you get really practical, and you talk about 12 specific lessons to save our lives. I want to ask you this question. This is something that I read, and it had such an effect on me that when I read it, I had to close the book and walk out of the room.

EE: My goodness.

BB: Yes. You write, “All therapy is grief work.”

EE: Not what happened, but what didn’t happen. I tell you a story. My little granddaughter, the sister of Jordan, was in a class where the IQ started at 145 and up. And I went to visit the class, and the teacher called my little Lindsey, “My little red caboose.” And Lindsey was a perfectionist. She would erase things 1,000 times, and Lindsey thought she doesn’t belong to that class, that she doesn’t qualify, and was ready to step out. And this is the first time I talked to Lindsey about Auschwitz. I don’t know how I said it, but I told her the teacher has no right to label her, that she’s a human being, and she has a choice. The choice is a big word, but choice from the labels that people put upon you. So anyway, she went back to the class, and when it was time to write application to colleges, you have to have an autobiography, and guess what was the title? When the Caboose Became an Engine.

BB: Oh, my gosh!

EE: And she ended up in Princeton, graduating with honors. Got her PhD at UCLA. And now, she’s Dr. Lindsey, professor like you. She’s your colleague. So, you have to be very careful not to allow people to label you. I’m no more and no less than a human being, that’s what I am. And as such, I’m limited, I’m not limitless. I can do the high kick now. It’s not going to be the way it used to be. It’s kind of halfway, and yet, I still do it, and people still love the halfway high kick. But that’s what happens with age. We don’t get old. We get older and wiser and think before I say anything. So, I celebrate the life I live in the present. I can only touch you now. I wish I could put you in my lap and hug you.

BB: Oh, I wish I could hug you back. I just really, one day, soon.

EE: You would. Maybe you’ll hopefully, one year.

BB: Oh, God! I hope so. We all need that connection so much right now. It’s hard right now for all of us in the pandemic. We’re just not built to be in isolation. We miss that community, that commitment to each other.

EE: And that’s what it took in Auschwitz. Because if you were just for the me, you didn’t make it. We had to commit ourselves and go beyond the me, me, me, and form a family of inmates. Just like hopefully, we’re going to be like people in Texas. There are good people in Texas. They have good neighbors. They commit themselves to each other. When I came to America, I was so impressed that the women in America paint their homes. They give themselves permanence. I never heard of such women in Hungary. So, I think that I’m a survivor and certainly, I am, today, blessed to speak with you as a wonderful survivor and not a victim of anything or anyone at any time. That is such a gift.

BB: That is the heart of your work. That’s the heart of what you teach us.

EE: It is. And I look at life as one day, and I’m at the evening part of my life, and I ask: How do I want to be remembered? And I know I’m going to be very happy in my deathbed because Elisabeth Kübler-Ross told us that death is the last celebration of life. So, to me, every moment is fresh as now. I watch Jeopardy every night. I’m totally addicted to Jeopardy.

BB: You love it?

EE: I love. I have my addiction. That’s my addiction. I love Jeopardy. And when I know the answer, I say it loud even though I’m alone in my bedroom. I am so happy when I know the answer to the Jeopardy. And the other night was Emile Zola and only I knew the answer. But don’t ask me anything about sports and many things that I know I never had heard before. So that’s why together — we are much stronger than me alone and you alone.

BB: Yes. We can each take one category in Jeopardy and win it together. Let me ask you about one more quote you have. My question is — this is so powerful to me — you write: “If you have something to prove… ”

EE: You are still a prisoner.

BB: You are still a prisoner. What does that mean to you? Teach us.

EE: This is the way I see things. I am the mother of my little boy, so I see my service to earth, but I don’t see the father and a son the same way. I think the son looks at dad in a more competitive way. They say, “I want to be just like him,” or “I want to be everything he is not.” So, Richard grows up and does his own thing, even though it’s not what his father wanted for him. It’s okay because he gives up the need of father’s approval. But if he wants to prove something and, “I’m never going to be like him,” he’s still a prisoner and a hostage and a prisoner of the past.

BB: God! It’s so hard to remember that… It’s easy to understand being just like someone can make you a prisoner if that’s not what you want but it’s so more complicated to understand that to live in reaction to someone your whole life still makes you a prisoner.

EE: Exactly. And that’s why it’s so important to reclaim your innocence and that’s why I went back to Auschwitz to reclaim my innocence. And I asked my sister to come with me, and I told her “Magda, I want to go back to Auschwitz. I want to go back to the lion’s den. I want to reclaim my innocence.” And she said, “You’re an idiot.” We went through the same experience, two entirely different responses, so who’s right? I’m right for Edith. I cannot be right for anybody else.

BB: That’s hard, right?

EE: Whoever said it was easy, look at your birth certificate. It doesn’t say life is easy. There is no easy life. There is no guarantee. There is no certainty. There is probability. And I choose in the morning how I’m going to feel at night, and at night, I feel satisfied. I want to work as long as I live because I don’t have a job. I have my calling just like you do.

BB: Yeah, people ask me how long do you work a day? I’m like, I don’t know because as long as I’m in my skin, I’m…

EE: Who’s counting?

BB: Yeah, who’s counting? I don’t know. I love my work.

EE: I like to quote Viktor Frankl. He’s quoting one of the German philosophers, and he said that, “When a midget stands on a shoulder of a giant, they can see further.” You see that we don’t want people to be like us, but they can really bring their own unique one of a kindness and not to compare with anyone. Just be your genuine self, so that’s why I ask the question — when did your childhood end?

BB: God, there’s so much pain in that question.

EE: Lots of pain.

BB: And there’s so much freedom in it as well.

EE: Yeah, because the more you suffer, the stronger you will become.

BB: Okay, I want to ask you a question, I’m really excited about asking you this question, it’s a question I ask every guest, but I’m bated breath for your answer. Fill in the blank for me. Vulnerability is…

EE: There is no vulnerability without fear, because if I’m vulnerable, they may be able to use it against me. It has to be trust to open up to someone who will not ever use that against me. So, trust would be… Vulnerability would be that I’m willing — I love that word — that I’m willing to risk. That’s a lovely word. I love that. That’s my favorite word in the English language. But when you risk, you suffer.

BB: Yeah.

EE: And it’s okay.

BB: Yes.

EE: Because it’s okay to feel feelings rather than talk about the feeling, medicate the feeling. It’s good to feel the feelings and say to yourself, “I don’t like it.” There is no forgiveness without rage. We don’t cover garlic with chocolate, but you can say, “I don’t like it. It’s inconvenient and it’s temporary, and I can survive it.” Not yes but, give me the but? I give you an and. “Yes, and… ” It’s everything is temporary. So, I think vulnerability is very important because if you are not able to be vulnerable, you’re not going to have intimacy either, because the biggest enemy is intimacy. Intimacy is the fear. And the fear does not ever co-exist with love.

[music]

BB: You write about going through so much pain and trauma and grief and despair in your life at such an early tender age. How did you and how do you continue to process the trauma, the anger, the rage about your experiences, about everything that happened, not only to you but the people you love?

EE: When you are angry, you got to be very careful because when you’re angry at someone, you suffer. When I’m angry at you, I give away my power to you, so it’s very important to be angry and then hold on to that anger and decide how long you’re going to hold unto it because while I’m angry at you, you don’t suffer, I do. So, people tell me, you know, you forgave the Nazis. I said, “No, I don’t have any godly powers, but I have power to not carry anymore, because if I live in anger and pain, I’m still a prisoner. I’m more than that. I’m a hostage of the past.” There’s one thing that I cannot change — it’s the past. I live in the present. I can only touch you now.

BB: So powerful.

EE: Thank you. It’s okay to be angry. Give yourself permission, but how long? It’s up to me because every behavior as a psychologist, I can tell you, you look for the secondary gain. So, if you want to tell me that you want to stop smoking, my question would be, “What’s good about smoking?” And you’ll going to tell me, “It’s my friend. I can reach for it any time I want to.” What’s good about being a victim? You can’t be a victim without a victimizer. And that’s what people do in coupleship. One is the victim and one is the victimizer, and they go back and forth and back and forth, and they come to see me, and all of a sudden, I don’t speak English. This is a couple who haven’t spoken to each other. And then pretty soon they look at each other and they want to help out the dumb Hungarian woman, and they’re talking to each other.

EE: So, you see, you got to have a way to recognize that emotion is energy, like everything else. So, if you have any emotion and when you are angry, then I go look for the pain that’s underneath that anger, the pain of not being accepted the way I want to. Then my mother told me, “I’m glad you have brains. You have no looks.” That was wonderful actually today, because I became a very erudite teenager. I had my own book club. I had a boyfriend. We had our own book club, and we had our goals. And I read The Interpretation of Dreams by Freud when I was 14 years old. So, you see, there is a way to change yes but to the yes and, yes, I was in Auschwitz, yes, I was in a hell. I never knew what’s going to happen tomorrow, 4 o’clock in the morning, I didn’t know, whether I end up in a gas chamber. When we took a shower, we didn’t know whether gas or water is going to come out. And that’s why it’s very important when we don’t know what’s going to happen next. And perhaps now is the time to unite, that we are all brothers and sisters. And I never give up hope. There is hope in hopelessness and not going back to have a new beginning. So, everything is time, T-I-M-E. Time. Love is time.

BB: Oh my God, that quote in the book. You said love is a four-letter word, spelled T-I-M-E.

EE: M-E. Time, I give you time.

BB: That’s the beautiful gift, right? Time.

EE: That’s the biggest gift I can give you, time. And when you said how much time you want to spend with me, I felt, I’m worthy. I’m so worthy you know when you go and you possibly are an addict, when the addict goes to a place, they don’t teach you how to control your drinking. They teach you how to give up your control.

BB: That’s right.

EE: You know the story about two drunks who went to see Jung and Carl Jung said to them that alcoholism can never be treated with psychotherapy. It’s a spiritual issue.

BB: That’s right.

EE: After body and a mind, there is the third dimension, the spiritual dimension, that I became a logotherapist, and talking about the existential, like him. Not clinical depression, where you have expectation on one hand and reality on the other, because you expected more and you’re getting less. You’re not upset when you expect less and you get more.

BB: No.

EE: So, you have to be a realist rather than an idealist, because when the idealist come and they don’t find exactly what they’re looking for, they become very cynical…

BB: Yeah.

EE: Sarcastic.

BB: And sarcasm is dangerous, right?

EE: That humor has a knife.

BB: I always think about the Greek origin of the word sarcasm — to tear flesh.

EE: It’s a person at the dinner table who’s listening to jokes, not listening to the joke what that person is saying, is how can he beat that person with another joke.

BB: Yeah. Painful.

EE: Yeah, I think it’s very important to think about your thinking and pay attention what you’re paying attention to, any behavior you pay attention to, you reinforce the very behavior that you want to extinct. Think about your thinking.

BB: In closing, I would love to get your thoughts on the country today, the US. I make up that it has got to be devastating for you to see the authoritarian rule that we’ve been subjected to and the anti-Semitism. Are you hopeful about our country?

EE: Of course, I am. We had the McCarthy eras, remember in the ’50s? Everybody was a communist.

BB: Yeah.

EE: Oh no, it’s happening. It’s good to be evolving, rather than revolving. My daughter calls it and “Edieism.” This is one of them — either you are evolving or revolving. And the second one is the opposite of depression is expression.

BB: The opposite of depression is expression.

EE: Is expression. Because what comes out of our body doesn’t make us ill. What stays in there does. In Hungary, they used to say to women, “Don’t breathe into your breast.”

BB: Don’t take that in?

EE: You take it in, and it doesn’t go away. These are the best patients in a hospital. I don’t want to tell my children. When the children come, “How are you?” “Fine.” You lie rather than saying I’m miserable. And to be really honest to each other, you have to be honest to you. If you want to be loving, then recognize that self-love is self-care. I’s not narcissistic. Narcissistic people don’t like themselves. I can tell you that because I’ve been doing this over 40 years.

BB: Narcissism is actually really full of shame, right?

EE: Full of shame, and you either want something what you don’t have, or you have something what you don’t want. That’s the simplest way. The older I am, the less I pathologize, I like to demythologize. There is no perfect family, there is no… Used to see Ozzie and Harriet on TV. That was before your time. It’s only on TV. I think we’re people. We’re human beings. We make mistakes. I personally climbed that mountain and I slip and climb and slip and climb, and never stop climbing.

BB: You are the gift. Both The Choice and The Gift are just beautiful life-changing manifestos. But you Dr. Eger, you’re the gift.

EE: Oh honey. You know, my children tell me that God doesn’t make junk and I love to listen to the children that we are here.

[chuckle]

EE: And we… Never get down on yourself. Just ask yourself what am I learning now? And what I learned in Auschwitz, to look at life from inside out and not to wait for somebody to make me happy and not to sing, “I am nobody ’til somebody loves me.” That’s horse manure.

[chuckle]

BB: Yeah, it is.

EE: Self-love is where everything begins and ends. We’re born alone. And I hope you will be looking in the mirror every morning and say, “I love me.” And I’m going to go back to my hairdresser because Edie told me that the blond is so attractive and when you have the blonde and the highlights. It’s just perfect.” I’m going to come to Houston, and we’ll go together to the hairdresser. And we’re going to talk about…

[laughter]

BB: I like some painted hair.

EE: You do? Everything is painted on me too. Everything is fake.

[chuckle]

EE: Everything is fake.

[chuckle]

EE: But I think it’s very important, again, to see that you love you, yes?

BB: That’s right.

EE: Not addicted.

BB: Thank you so much for spending this time with me today. You are amazing.

EE: I love you so much for doing your calling and I hope we’ll meet and sing together.

BB: Oh, I would love that.

EE: And love each other and have good Texas meat. I go to Texas. I want meat.

[chuckle]

EE: I want a good American prime rib. I love good American beef.

BB: I’ll make you a deal. Come to Texas.

EE: Yes.

BB: I will get you the best steak ever. We’ll get our hair highlighted together, more blond paint.

EE: Sounds great.

BB: And I need some Hungarian chocolate cake.

EE: Well, that is…

[laughter]

EE: That is something… Saying something wonderful. Just for you, I’ll bake a Hungarian chocolate cake, and I’m going to make it actually and send it to you.

BB: We’ll have it together.

EE: Yes, on that. Keep smiling. Your eyes are beautiful. I love your smile. And I am just so, so grateful that we met. Hopefully, we’ll be friends for life.

BB: I would love that so much, Dr. Eger. Thank you.

[music]

BB: Sometimes you just talk to people who take your breath away. It’s just her resilience, her courage, and her love. I mean, just… It’s like sometimes you sit across from someone and you’re just like, “Man,” and we were on Zoom, and you could still feel the love bubbling over. And I would love nothing more one day than to have her here in Texas because she visits Houston. She’s got family here. We can eat barbeque and some Hungarian chocolate cake.

BB: You can find her books, The Choice and The Gift, wherever you like to buy books and we’ll link you to them as well on our episode page. You can find Dr. Eger online at Dr. Edith Eger on Instagram. It’s D-R. E-D-I-T-H E-G-E-R. She’s Dr. Edith Eger on Facebook, and her website is dreditheger.com. Just don’t forget items from the Church Bulletin. Every episode of Unlocking Us has an episode page where you can find resources, downloads, and transcripts. You can always sign up for our newsletter once you’re on the website as well.

BB: Thank you for joining us for this really beautiful… I’ll never forget these words. How do you spell love? T-I-M-E. God, it’s so powerful and true in this world today. Y’all stay awkward, brave, and kind. And spend some T-I-M-E with the people you love. I’ll see you next week here on Spotify.

BB: Unlocking Us is a Spotify original from Parcast. It’s hosted by me, Brené Brown, it’s produced by Max Cutler, Kristen Acevedo, Carleigh Madden, and by Weird Lucy productions. Sound design is by Kristen Acevedo, and music is by the amazing Carrie Rodriguez and the amazing Gina Chavez.

© 2021 Brené Brown Education and Research Group, LLC. All rights reserved.