Brené Brown: Hi, everyone, I’m Brené Brown, and this is Dare to Lead. Today I’m talking with Liz Wiseman, author, researcher, and executive advisor, about her new book, Impact Players: How to Take the Lead, Play Bigger, and Multiply Your Impact. God, I loved this conversation. It was so good, because I think, if asked, most of us could say, “Here are my impact players.” I think the term comes from sports and we all know the impact players on the sports teams that we watch and love. But even at work we can tell you who the impact players are, the people who really make a difference, not even with getting stuff done, but the spirit and culture of the group. And so Liz has done one of my favorite things, which is taking a concept or a construct and defined it and backed into it so we know what makes an impact player, what are the attributes. She’s done research across organizations across countries where she talked to managers about what an impact player looks like, what sets them apart and how they contribute. I read Liz’s book, Multipliers, a few years ago and her new book, Impact Players, really takes that work, gives it new research, new breath, and gives us new language about how to make our work and our impact more fulfilling. I can’t wait for y’all to hear the conversation.

[music]

BB: Before we get started, let me tell you a little bit about Liz Wiseman. She is the author of the book that we’re going to be talking about today, Impact Players. She is a researcher and an executive advisor who teaches leadership to executives around the world. She is the author of the New York Times bestseller, Multipliers, and the author of The Wall Street Journal bestseller, Rookie Smarts. She’s conducted significant research in the field of leadership and collective intelligence, she writes for Harvard Business Review, Fortune and a variety of other business and leadership journals. She is a frequent guest lecturer at BYU and Stanford University and is a former executive at Oracle Corporation, where she worked as the vice president of Oracle University and as the global leader for Human Resources Department. Let’s jump in. Hi, Liz, and welcome to Dare To Lead.

Liz Wiseman: Oh, it’s so good to be here. I kind of made a list of things I wanted to talk to you about and it was more than a dozen things. So I’m excited for this conversation.

BB: Well, I have a list that’s probably more than a dozen things too, so we’ll see what we can cover. I feel like our paths have crossed a million times out in the world, but this is the first time we’ve ever really met. Right?

LW: Well, we met briefly… We were both speaking, and I think you yelled from across room, “Hey, you’re the Multipliers lady,” and I’m like…

BB: Oh God. [laughter]

LW: And I’m like “Hi Brené.” And so it’s like, we’ve met in passing so many times.

BB: Yeah. It’s nice to be face-to-face. Passing, yes. Alright, let’s start here, because I want to really get into Impact Players, the new book, and I have to say I’ve got a lot of it highlighted, I’ve got a ton of notes and a ton of questions. So first, tell us your story.

LW: Oh, my story. Well, let me maybe start from the beginning and how I got to do this work. I’m a native Californian, I’m the daughter of a teacher. My mom was a teacher and my father was a donut maker, and our family made our way up from Los Angeles to San Jose so my dad could start a donut shop, and he’d gotten kicked out of the family business, which was a mortuary. And so he’s kind of going through a bunch of career failings, failures, and our family makes our way up to San Jose. My dad had a lot of influence on me. My dad was a pretty difficult person, he was prickly. He was exactly the kind of person you wouldn’t want planning your family’s funeral, he was…

[laughter]

BB: Got it.

LW: Do you get the picture? Like, not particularly sensitive. He was bossy, he was critical, he was always telling people what to do and what was going to go wrong. And when he wasn’t kind of in know-it-all mode, he would then withdraw and he would kind of go into this sullen withdrawn mode. And he was a father who didn’t express any affection, and people found him to be really, really difficult and intimidating. And people tended to withdraw from him, and they might have even saw him… My father was in no way abusive, but he was difficult and certainly not warm and fuzzy and friendly. And people tended to pull away from him. And I just saw my dad different from a really young age, and I think it ended up shaping my whole life and shaping my whole career. Because while other people saw him as a little bit hurtful maybe, I just saw, wow, this is someone who’s been hurt.

LW: This is someone who’s hurt. And I saw like, he’s not disappointed in us, he’s disappointed in himself, and this is someone who has been hurt in life. And I don’t know why I saw it, but I just did, and I kind of reacted to him differently. Where other people sort of pulled away or got into arguments with him, I just sort of stood up to him, because I think I concluded, this isn’t a scary person, this isn’t someone who wants to see me fail, he’s trying to help me be successful.

BB: Yeah.

LW: So I responded to him a little bit differently, like, “No Dad, that’s not fair, let’s do it this way” and he’d be like, “Okay.” And just over and over I reacted to my dad very, very differently than the other people in my family to the point where I became the spokesperson for the three other kids, which is like, “You go ask Dad to do it, you’re not afraid of him.”

BB: Yeah, that’s not easy. Yeah.

LW: And so I become that spokesperson, and fortunately I had this very nurturing mother, who was a teacher. But, you know, my dad was difficult and I remember wishing, “I wish I had one of those dads that my friends had.” One of these like, “Oh, you know what, let me sit on knee, let me teach you life’s lessons, let me support you, let me help you.” I’m like, “Why do I have a dad that’s kind of hard on people? And I wish I had one of those kind of dads.” And I even remember in college one of my roommates came and stayed with us in the summer, and she was upstairs and I’m downstairs talking to my dad and I’m about to buy my first car. I’m in graduate school and I’m going to buy a car and he’s going to help me, and we go through the normal thing, “Well, that’s not going to work, and this is going to be a problem.” And I finish up that conversation, I go upstairs to my friend, my roommate, and I’m like, “Okay, let’s head out.” And she’s like, “Were you talking to your father?” I’m like, “Yeah, you know, I’m going to buy a car… ”

LW: And she’s like, “Is that how your dad talks to you?” And, Brené, this might have been like one of these first moments where it could have been a very shameful experience and she’s in shock, because she sees me as this college student who’s, I don’t know, confident and a good student. And she cannot believe this is like… I’m like, “Oh yeah, that’s my dad. He just, he doesn’t want me to buy a bad car and he’s trying to help.” And she just couldn’t believe it. And so I’m like, oh, man, it would have been great to had a really supportive dad. And I go off to college, I end up gravitating towards business and organizational behavior, very fascinated by human nature. I graduate, I decided I want to go out and teach leadership, and so I’m like, “I’m going to go find me a job where I can teach leadership.” And…

BB: Yeah.

LW: I contact Zenger Miller at the time, and I’d somehow worked my way into talking to the president of the company, and I’m like, “Here’s my resume, hire me to teach leadership.” And he’s like, “Liz, if you want to teach leadership, maybe you should go get some experience leading.” And I’m like, “Oh man, this guy doesn’t get me.”

[laughter]

LW: “He doesn’t understand. This is my thing. It’s my jam. This is me, and I want to do this, and I’m passionate about it.” And he’s like, “Go get some experience managing.” And so I took this back-up job, and I did not really want this job, but my backup job was an offer… I had at Oracle, which was this young growing software company. So I go to work there, turned out to be an amazing experience, and I find myself working with all these super smart, super driven, really, really bright, driven kind of people who could be kind of overwhelming and intimidating and…

BB: Oh yeah.

LW: I find myself in this sea of people and I responded to them differently as well. You know, when there are all these intimidating people, I’m like, “Well, I’m going to start to stand up for myself and my ideas. I don’t think they’re trying to hurt me, they just have an opinion, but I have an opinion too.” And I didn’t wait until someone gave me an opportunity, I was just like, “I can do that.” I mean, these are all skills I learned kind of working with my dad. I’m like, oh yeah, when you stand up to people who seem intimidating, they kind of respect you and they soften, and I reacted very differently. And then I got thrown into management, because the more I said, “Oh, I can do that, I can help with that, oh I have an opinion,” I guess the more courageous I was, the more opportunity I got. Now I’m working in management and in senior management, I’m working with the senior executives who were some pretty intimidating people.

LW: And I remember people used to say, “Liz, you worked at Oracle? Aren’t they kind of like tough people there? Like, isn’t Larry Ellison kind of scary?” I’m like, “Larry Ellison, scary? Have you met my dad?”

[laughter]

LW: “Are you kidding? Larry Ellison, he’s nice, I mean he’s a sweetheart.” And I just saw these leaders differently. I’m like, “Oh yeah, you know, that person is a total know-it-all, I see it, but it’s not the effect they’re trying to have. Like, yeah, okay, that’s not necessarily great leadership behavior, but they’re trying to do a good job.” And I could see that their intention was very different than the impact they were having and it was so easy for me to see, because I’m like, “Wow, I’ve been like training my whole life for this.” And I think it was my early experiences that caused me to see managers and leaders very, very differently and to see in these cracks between what people want to do and what they’re trying to do, like people’s most noble intentions, and the actual effect they’re having on other people. I’m like, “Oh, there’s a mismatch here.”

LW: I see things, like some people see ghosts, I see intentions and I see them everywhere I go, just like, “What’s that person really trying to do?” And it helped me, and I think I just learned to see things from other people’s point of view and work from that. I was at Oracle for 17 years, had an amazing experience there, had a lot of responsibility there and then I left and started doing some coaching work and saw a bunch of similar dynamics with people trying to be good leaders, but having this kind of diminishing effect on others and coaching experience and my observations there said, “Oh well, someone needs to research this, no one’s studied this.” And so, started doing research work and was like, “Oh wow, this is kind of fun. It’s fun going from something I don’t understand, to data to now understand something, and to share it.” And so it went from coaching to research to writing and teaching, and that’s really where… What I do. And kind of the work I do today is… And, Brené, you’re going to die when I say this, it’s like my work is really all around intelligence and how intelligence gets wasted inside of organizations, and what it really looks like to contribute intelligence and knowledge and insight fully.

LW: And, in some ways, whole-mindedly. And when I started this research, I was like, “No, this is about intelligence, not emotion. It’s not about emotion, this is about the effect that leaders have on intelligence and how people use their intelligence.” And after a while, I start to see, oh, well, it has a lot to do with how people use emotion and how people respond to emotion. So you can’t really have whole-mindedness without whole-heartedness. But it took me a little while to figure that part out.

BB: Me too.

[laughter]

LW: And that’s really what I do… I think you figured this out much sooner than I did. But my work is all about how to help people contribute fully. If I’ve learned one thing from my own experience, my story I suppose, and, man, this is true all over the whole world, I’ve learned that people come to work, desperately, desperately wanting to contribute everything they have. Like I can’t find the people who don’t want to show up and play big, I just see people who come to work with this hope of, “I want to be smart, I want to contribute, I want to be part of a team, I want to do something amazing.” But then I’ve watched how leaders can get in their way, how they can get in their own way, and how desperately they want to contribute and how painful it is when they can’t.

BB: I would say I’ve learned the exact same thing. And it is heartbreaking, in a way, because there is a grief attached to not being able to make good on that goal of wanting to contribute. There is real grief, and people don’t understand what’s happening.

LW: It’s grief and it’s exhaustion as well, and it’s one of the things that has been so interesting to me, is people describe this experience of being busy but bored or working hard but being under-utilized, not having their gifts and their talents utilized. They say it’s frustrating, of course, but it’s exhausting. And isn’t that…

BB: Yeah. I can see that.

LW: I just find that fascinating that we find it exhausting when we can’t contribute, when we’re working hard but not having impact.

BB: Right, because contribution is exhilarating. Contribution is life-giving. So I could see how the opposite, not being able to contribute, not being able to shine, is just like death by paper cuts.

LW: It is. And I think it is hard sometimes for people to understand. And one of my favorite reactions to my work on the leadership side of this, is people saying, “Wow, I now understand what was going on and why that was such a painful experience to me. I was hurting because I couldn’t contribute.”

BB: Wow. Okay, let’s jump into… I really… You have to just pause for a second and say, I really appreciate the honest, vulnerable sharing about seeing your dad in a different way than other people saw him, and navigating that relationship really gave you skills and a lens to do your work. There’s no Freudian secret about why I do the work I do, but I don’t think enough of us talk about how some of the things that were hard for us and some of the obstacles that we faced and some of the struggles gave us skills that make our contribution so powerful and unique. I just don’t think we talk about them. So I really appreciate your honesty.

LW: I’ve gone from, “Man, I wish I had one of these warm fuzzy, nurturing dads,” to, “I’ve learned so much from that experience, and I’m so grateful I had that experience, and I don’t know that I could do what I do without having had that.” And my relationship with my father was tender. He passed 20 years ago, but we ended up with this close, tender relationship. And I just saw how seeing people differently and looking at what people are trying to do, and seeing other people’s hurt before seeing your own, or even just going to the place of like, “Wow. In what way is that person hurting?” It just allowed me to get so much joy out of that relationship.

BB: It’s really powerful. And tough.

LW: Yeah, it wasn’t easy.

BB: It’s not easy and there’s probably boundaries and lines that would make it untenable, but it is really how we get to a lot of our strengths and a lot of our intelligence, emotional and cognitive. Let’s talk about Impact Players. Wow, there are a couple of quotes in this book that just made me freak out, made me stop and think. So let’s start with this, how would you define what an impact player is?

LW: An impact player, let’s start with, it comes from the sports world. And there are people on a team who are enormously talented, who make great plays, they do great work, but they also make the whole team better. So we see this same dynamic in the work world, there are people who are just these stand-out contributors; but not only do they make a valuable contribution and do impactful work, they kind of raise the level of play for the whole team.

BB: It’s so funny because before I read this, I know who the impact players are, but I couldn’t have defined why. So what I love is research that takes something we all know but we are not able to language. You define it for us, you give us the anatomy of an impact player so that we can become it, we can learn it, we can recognize it, we can appreciate it, we can value it. But I love that, because if you asked any leader that I’ve worked with, I’m sure, over the last 15 years, who are your impact players, they would be able to rattle off the names in a split second. And if I said why, they probably couldn’t tell me.

LW: That’s exactly what I found in the research. So my team and I interviewed 170 managers and they know who their impact players are right away. And it took them a little bit of time to think, “Why is it? What is it that they do?” And we were asking managers and senior leaders not to describe like, “Give me a top performer, and then a bottom performer that you really wish you could move out of the organization.” We said, “Compare them with someone who is doing a solid job. You know, a typical contributor, someone that you wouldn’t mind having 10 or more of these people and your team,” and so we’re looking for, what are those fine distinctions?

LW: And it was in this process of talking it through with us, they’re like, “Yeah,” I think… “Now, I know this, je ne sais quoi, I couldn’t figure out why it was I always gave the most visible assignments, the most important, most critical clutch moment over to this person,” and that was the thrill of this research, is finding out, what are these small differences in how we think and act at work that allow us to have this huge impact, not for the companies that we work for or those managers, but for ourselves. That’s what I’ve really learned, is that when we go through the motions at work, it’s draining, it’s painful, it leads to burnout, but when we can have a huge impact and do work that’s meaningful, it just feels great. Work’s a thrill.

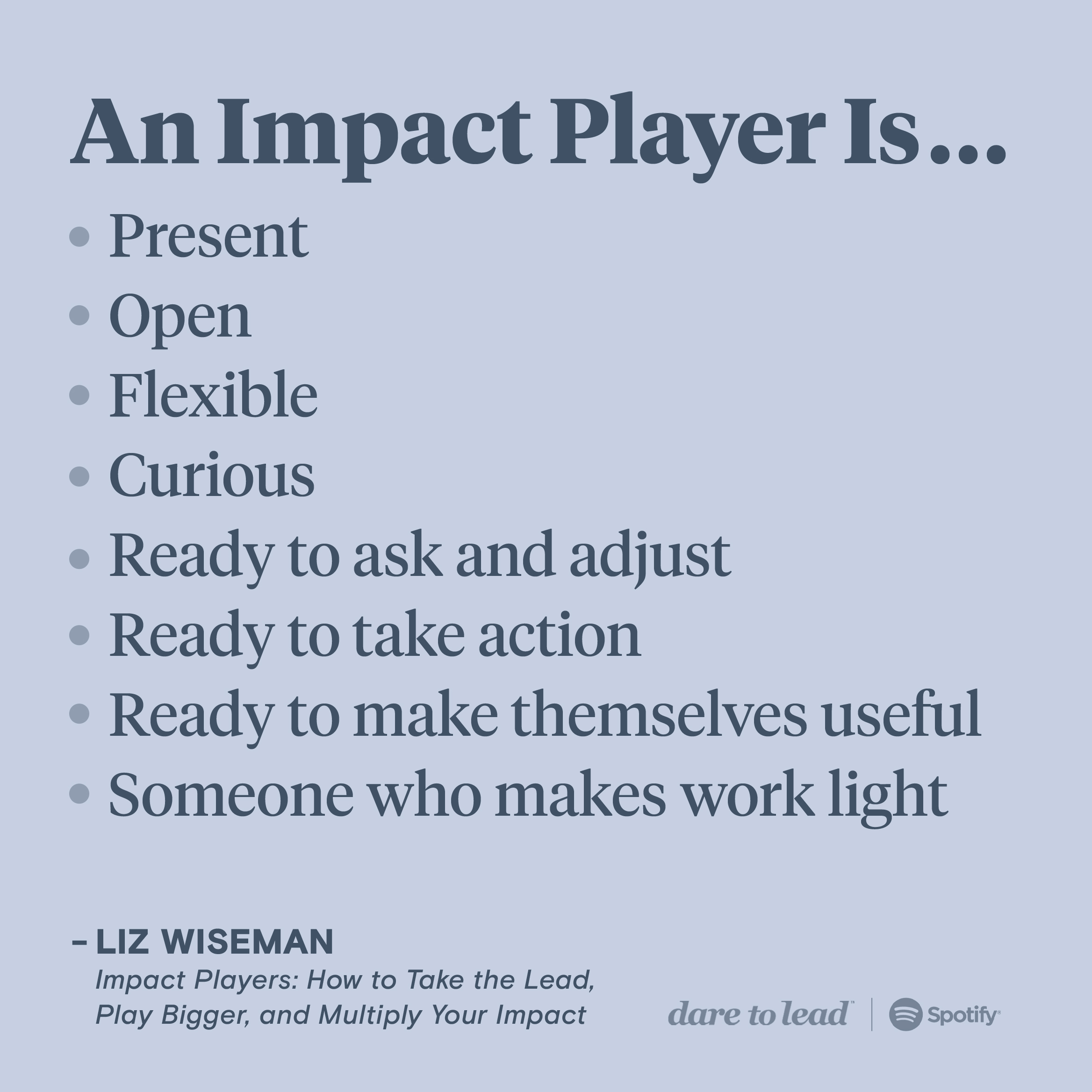

BB: Oh my God, good work can be a thrill. I mean a huge thrill, I love this. “It’s time to examine what the best contributors do, how they create extraordinary value around them and how that strength strengthens their voice and increases their influence in the world.” This is from your introduction. So, how do you define and articulate what an impact player looks like? And so this is your summary, “Present, open, flexible, curious. Ready to ask and adjust, ready to take action, ready to make themselves useful and they make work light.” Tell me about readiness and impact players.

LW: So I’m a mom, I’ve got four kids. I’ve been to a lot of sporting events. I’ve watched a lot of soccer matches and football matches and… You know what’s funny? I have a hard time watching what happens on the field because I am so busy watching what’s happening on the sidelines.

[laughter]

BB: Me too! This is a researcher’s dilemma right here.

LW: It is, because I’m watching the coach. I’m constantly looking the coach…

BB: Me too.

LW: Not for like, “Put my kid in!” I’m like, “Are they hot-headed or are they keeping their cool?” So I’m constantly watching the coaches, but I also watch the players on the sidelines, and there’s two different postures when you’re on the sidelines. One is, “Oh, okay, Coach has got me out, let me chill, let me like good around with my friends,” and the other is that ready posture of, “I could be put in the game in a moment’s notice, and I want to be ready. I’ve got my helmet on and I’ve got my eyes on the field. I know what’s happening.” I had a son who played high school football, so I can think of so many scenes when a kid gets tapped on the shoulders, like “You’re in” and they’re like, “Oh, where’s my helmet?” And they’re like, “What’s going on? Are we on offence or defense?” like, “What’s happening?” And it’s this ready posture of I am ready, kind of at a moment’s notice to do what’s needed, and to do that, you’ve got to know what’s important, you’ve got to know where you can contribute, so it’s being ready to put in the game.

BB: It’s so incredible that you talked about this, because I’ve got a son who’s a very competitive water polo player, and I watch the bench all the time because there’s a lot of subs in and out of water polo, because it’s so exhausting. And there are kids that are… Their hands are on their knees, they’ve got their caps on, they’re leaning forward, they know exactly what’s going on, and when someone raises their hand because they’re hurt or they’re exhausted, they need be pulled out, that person’s standing even before the coach turns to the bench. And then there’s also the kid who gets out of the water, and the coach is like, usually they’re really physically moving the kid around showing help, and the kid’s not trying to get to the bench and away from the feedback in front of everybody, the parents, the teams, the opponents, they’re asking more questions and pushing into the feedback and it’s so visible.

LW: It’s visible and you think about it, like… Think about when we feel overwhelmed and it’s like you’ve got way too much to do as a leader, you need to delegate to someone, and someone comes up to you and says, “Hey, can I help you with this?” You make a decision of, “How long would it take for me to get that person up to speed?” And there are some people where you’re like…

BB: Oh, my God.

LW: “I so want to take you up on your offer to help, but you don’t know what’s happening on the field. You don’t know what’s going on in the game right now, so it’s going to take me so long to get you game ready that I can’t use the help”, versus the person who’s like, “I’ve been watching what you’re doing, I’m watching what’s going on. I know what’s needed. If you give this to me, I can contribute right away.” It starts with this ready posture.

BB: That’s really powerful because… I wonder too, let me ask you this question. If you’re trying as a leader to nurture and value readiness, how much responsibility do you have to take for making… Because we’re not in a pool or on a football field, we’re in an office where people can’t see everything like that. How much responsibility do you have as a leader of always making sure that people have context and understand what’s going on in the game so that… Do you have to set a table for readiness in some way?

LW: Oh wow, okay.

BB: Does that question make sense?

LW: It’s such a great question because it gets at the heart of it. So as I was going through this research, “What do these impact players do?” I thought, “You know what? A lot of this seems like the leader’s job to me.” That’s the manager’s job to give people context, let them know where they can contribute, how they can contribute, and I think it’s one of these things where it’s actually two sets of 100%. So, I’ve spent the last decade out teaching managers what they need to do to create an environment where people can contribute fully. So I’m so steeped in what is the leader’s job? In this piece of research, what I did is I said, “You know what, irrespective of the leader, what do the best contributors do?” And in some ways, what they do is they do a lot of that leader’s job for them, and it’s not really to enable lazy leadership but it’s like they’re self-managing. On this particular case in point, here’s what I learned from 17 years in the corporate world, is I learned that nobody is going to serve up to me on a platter, a real sense of what’s important.

LW: To figure out what’s really important and what’s going on in the organization, yeah, sure, I’m going to look at the annual report and I’m going to look at the strategic documents that the senior leaders are sending out, but I’m also going to pay attention. What’s going on? What gets talked about? Yeah, it’d be great if my manager would tell me what her top priorities are, but in absence of that, I’m going to pay attention. What does she seem to care about? What does she spend her time on? I’m going to fill in those gaps and… So the answer is, yes, it is a leader’s job to do this, but the best contributors and the most impactful contributors and influential don’t wait for their leaders to do it. They’re self-managing and as we’re dealing with so much uncertainty, managers need people on their team to be more self-managing, which enables two amazing things to happen. One is when people on the team self-manage, then the leader can actually lead rather than micro-manage the team.

BB: That’s powerful.

LW: It frees the leader up to actually be the kind of leader that you and I talk about.

BB: Yeah.

LW: Because you can’t do it if you’re having to say, “Oh, by the way, I need you to do this and have you done this?” If the leader is dragged into that space, they can never do a great job creating the trust that’s needed on a team, the sense of belonging on a team, the sense of navigating through uncertainty and the learning that needs to happen. The second thing is, when we self-manage, we get the dignity of not being managed.

BB: Yes.

LW: Because I think this is what I see today. No one really wants to be managed, they want to be led, and most managers don’t want to manage.

BB: I want to stop you right there. This is such a huge pivotal distinction that people don’t understand. Tell me what that means, that people don’t want to be managed, they want to be led. Tell me the difference between being managed and being led.

LW: Okay. Well, let’s just work it out and anyone listening, let’s work this out. What does it feel like to be managed?

BB: It feels at times manipulative. It feels controlling. It can feel like there’s a lack of trust. Yeah, I don’t like to be managed.

LW: Oh, I don’t like to be managed. For me, it probably goes back to my childhood with…

BB: Yeah, mine too.

LW: I learned to assert myself like, “Oh no, no, don’t tell me what to do, don’t tell me what I can’t do,” but what does it feel like when we’re the recipients of great leadership? What does that feel like to be led well?

BB: Exciting. Freedom. Trust.

LW: Yeah, to be trusted.

BB: Yeah.

LW: Yeah, like someone’s going to say, “Here’s where we need to go, but I’m going to let you figure out the best way to navigate there.” I’m like, “Okay, yeah, this is like an adult job. I like it.”

BB: Yeah. Okay, so let’s go back to people don’t want to be managed, they want to be led. And as a contributor, what do I do to increase the odds of leadership being extended to me and not management? What behaviors do I engage in that ensure that I’m going to continue to be managed?

LW: That’s such a fun question. If you want to continue to be managed, then take ownership, but don’t necessarily follow through. Do your part, but don’t look at the bigger picture. Carry your weight on a team, but don’t necessarily look for opportunities to help. Wait to be asked to do something before doing it. Identify problems, but don’t bring solutions. These are all the things that keep us being managed. In fact, it was one of the fun parts of the research. Whenever I plan my research, I kind of plan very logically the questions we should ask and the behaviors, mindsets we should survey on, and then I throw something on there just for me, like what I want to know, it’s my very selfish part of the research, and one of the things I wanted to know was, what is it that people do that you most love, that you appreciate that when people do it, you’re like, “I love my job”? And I can actually lead, not hover all over people. And then I also asked, “What do people do that you really hate? What makes you hate being a manager?” And it was fascinating, and there was so much consistency on these two lists.

BB: I’m dying, I’m on abated breath. Tell us the answers.

LW: Well, I’m going to actually pull out my list, I’ll give you the top five on each.

BB: Yeah, that’s great. I love this.

LW: Okay, top five things that bosses hate. There’s 15 of them, but this is a surefire way to infuriate one’s boss, and let’s see, number one, give them problems without solutions.

BB: For sure.

LW: Number two, make them tell you what to do or wait for them to tell you what to do. Make them chase you down and remind you. Don’t worry about the big picture, just do your piece. Ask about your next promotion or raise, which is an interesting one because there’s some gender issues in that that are…

BB: 100%. And people of color.

LW: Yes, absolutely. So that one’s got some nice texture to dig into. I’m going to give you maybe six as well, send long meandering emails. That’s like a sure fire way to infuriated one’s boss. Okay, now here’s the top five things of what bosses love when people do these things. Do things without being asked. Anticipate problems. Have a plan. Help your teammates. You know, this is one when I was looking… Well, that’s number three on the list, is like when people help their teammates… And I was thinking about it. I have four kids, so I’ve got a bit of a brood and I loved having four kids, because it was almost like big enough for a research pool. Like an N of four here. I could see some interesting things, but as a parent, I would always remember what it was like trying to get four little kids out to the door.

BB: Oh, yeah.

LW: And one of the things that you appreciate the most is when one of the older kids would say, “Oh, let me help the younger kids get their jacket” and you’re like, “Thank you, I so needed that,” I couldn’t be everywhere all at once. And leaders in the workplace are the same way, it’s like, “Man, I can’t be with everyone at once, so if you could be my surrogate, if you can help me lead the team… ” And it’s not just like, help your colleagues like do their work in the background, it’s be a deputy for me. And think it’s what I found in these impact players, is they get deputized by leaders.

LW: And…

BB: That makes sense to me.

LW: Okay, so let me see, number four on the list, do a little extra. Get the job done, and they’re like, “I love it once one does it and then just as one tiny little extra thing” like, “Oh, gee, I’ve just taken the liberty of summarizing three key points on this report. Thought that might be helpful.” Little things that don’t take much work to do, but you’re like, “Man, that person was thinking what it was like to be me, what it would be like to have a 30-page report dropped on your desk the day before the meeting and they just took the effort of summarizing that for me.” That’s amazing. Okay, number five is, be curious and ask good questions. And I think one of the things I’ve learned is that bosses don’t want to be bossy. They want people who are stepping into that leadership role, who are helping them not just be self-managing, but helping to lead the team.

BB: I love this. Can I read something to you from your book?

LW: Okay, and I hope it’s not the worst part of it.

BB: No, it’s great. I love the title of this subsection within the chapter and I love this. So, “Impact players wear opportunity goggles. Our data made it clear that the approach taken by impact players isn’t just marginally different, it’s radically different, and it’s rooted in how these professionals deal with ambiguity and situations they can’t control. While others get frustrated and either check out or freak out, impact players tend to approach such situations directly yet sensibly. They dive into the chaos head-on, much as a savvy ocean swimmer dives into and through a massive oncoming wave, rather than panicking and being tumbled in the surf. Virtually all professionals deal with waves of ambiguity regardless of where they work. There are problems everyone can see but no one owns. Meetings with many participants, but no clear leaders; new terrain with never before seen obstacles, goals that morph as they get closer and work demands that increase faster than one’s capability grows.” Impact players wear opportunity goggles. Whoa.

LW: Here’s the first thing I found in this research. So, I’m looking for behaviors and mindsets, that’s kind of my thing, I’m constantly looking, what are the mindsets and assumptions as well as the behavior that differentiate people in certain circumstances? And when I looked at all of these behaviors and the circumstances, and I kind of stepped back from… I remember I was on a flight back from Phoenix and I looked at it, and I was like, “Wow, these are the kinds of problems, these aren’t big, massive crisis problems. It’s everyday problems.” There’s a clear problem here, but I don’t know which department’s responsible. It’s not really my job, but it’s not his job. It’s like nobody’s job but everybody’s job. That is where impact players work differently. Most contributors would say, “Okay, let me do my job,” but the impact player goes out into that white space and says, “You know what? This isn’t my job, but it’s the job that needs to be done.”

BB: Oh my God, let’s just stop right there. “This is not my job, but this is the job that needs to be done.”

LW: We see this over and over as they don’t get overly attached to their job descriptions or their job boundaries. I think it’s one of the most damaging thing we’ve done in organizations, is put together org charts and boundaries, because it’s all saying like, “Here’s where you’re not supposed to go,” but… Most problems are messy, certainly when you’re out trying to innovate and doing something creative. In times of uncertainty and ambiguity, problems don’t come neatly packaged for a department or a person, which means people have to expand their range. I had my own experience with this.

BB: Tell me.

LW: Well, I came into Oracle, this was my backup job, I wanted to teach leadership. And so, you know, I’m going about my job and I worked there for about a year, and I have this opportunity to go work for this internal training group that did mostly technical boot camps for all these new hires. You know Oracle is a software company and we’re hiring all these hotshot programmers from around the world, and I’m like, “Oh, that group does technical training, but their charge is going to expand to include management training, and maybe I could expedite that.” Because young people were being thrown into management jobs, have no idea what they’re doing, weren’t getting any training from the company and they’re like, wreaking havoc on their teams, and so I’m like, “Well, I bet I can. I ended up writing a book about this, but I could see it.”

LW: And I’m like, “I bet they need someone to come teach leadership,” and I’m like, “This is my moment, that’s my thing, that’s my passion.” And I’m interviewing for a job in this group and I interview with the director of the group and I’m interviewing with the Vice President, a man named Bob, and I answer his questions and then it’s sort of my time to ask him some questions, and so I shared this observation, “Hey, seems like the company needs management training” and he agreed. And I said, “I think Oracle needs a management Boot Camp and I would love to work on that, I would love to help build that.” And Bob, he said to me, he was polite, he said, “Liz, but your boss has a different problem, she’s got to figure out how to get 2,000 new college grads up to speed in Oracle Technology over the next year, and what would be great is if you could help her to do that.”

LW: And I’m like, “What? Technology? I want to teach leaders.” And Bob wants me to now teach programming to a bunch of nerds, and I’m like, “That’s not what I want to do,” but I could hear… I think it’s because I sort of learned to see what’s the back story going on behind things. I was like, okay, what he is essentially saying is, “Liz, this is what’s important, getting people up to speed in technology, and why don’t you make yourself useful here?” Those words, he didn’t say them, it’s what I heard, “Liz, make yourself useful.” And I thought, “Well, it’s not what I want to do, it’s certainly not the job I want, but it is the job that needs to be done, so let me get over myself and what I want, what I’m passionate about, what I care about.” I mean, he just pointed out the biggest problem.

BB: Right.

LW: And so if he just showed it to me, then let me go work on that. And so I said, “Okay, I’ll be a technical trainer,” and I had no qualification really to do this, but I figured out how to do it and it was amazing what happened for me, because I did that. Suddenly, they need a manager for the group, “Liz, we want you to do it.” Like, “Why me?” And they’re like, “Because you understand what’s important, you understand the technology.” And then the jobs, the bigger jobs just kept coming and coming, and I learned, make yourself useful, figure out what’s important to your boss and make it important to you, and you’ll find yourself working on the most influential work and you’ll actually have a much bigger impact. You can either go do your little thing, or you could go point yourself towards the big thing and have a much bigger impact. And that was my own experience, but I had to get hit on the head with a brick. Someone saying like, “Liz.”

BB: Oh, yeah.

LW: Like, “Make yourself useful.”

BB: Yeah, me too, I had a very similar experience, because I went to work for AT&T, and I really wanted to be in the leadership and organizational development training team. And so my first offer, kind of outside of non-management, my first management offer, this was back when 900 numbers were really problematic, and so it was a 900 number Investigation Team that needed leading, and I was looking over across the company thinking, but I wanted to be over there and I wanted to do leadership and org development work. But it was a real crisis because people’s kids and partners were running up thousands of dollars in 900 numbers, and they were getting their phones turned off at the time when there was no mobile phone, it was a crisis for the phone company and for the clients.

BB: And so I remember thinking, “This is not what I want to do, but they’re in a crisis and they’re choosing me to try to lead them out of this crisis, and this feels like I need to do this.” And it was interesting because I did it and I did it for probably a year, and then the next opportunity that came open was, what was it called back then? CQI, Continuous Quality Improvement Team, like TQM and CQI and all that stuff. And then they came to ask me for that because I had helped and then I eventually ended up in leadership and org development work.

LW: Where you probably could do work with much bigger impact because you understood the problems better.

BB: Yes, and I tell people all the time, especially young folks at work, I’m teaching an MBA course at UT Austin right now, nothing wasted. Leading a 900 number investigation team made me a better researcher. Before I was promoted being a union steward made me a better activist.

LW: Absolutely.

BB: It’s like nothing’s wasted.

LW: And for me, I take on this job, I’m now teaching programming to a bunch of hotshot programmers from Caltech and MIT, I still consider this like the ruse of my career, that I figured out how to do this, but… because I’m like, “They don’t know I don’t know what I’m doing,” but I partnered up with a colleague, Lesley Stern, and she was a properly trained programmer, and she’s like, “Liz, we’ve got to teach you to think like a programmer,” because I would be working with all these applications and tools and making a mess of things and like, “Oh, it’s best, let me fix all this.” She goes, “Liz, think like a programmer, isolate one problem, put in a solution, re-compile your code, and then once that works, then put the next solution in place.” Well, guess who learned how to think like a good researcher.

BB: Right.

LW: And it was like insubordinating my will that I was given the most important work and I learned the skills I needed to do this work that I love so much, that’s how I learned to be a good researcher, isolate, create apples-to-apples kinds of comparisons. Introduce one solution at a time. And going back to your observation, it’s like impact players wear opportunity goggles, so you could look at that situation and go, “Well, that’s not the job I really wanted,” but you’re like, “but it’s what’s important, and there’s an opportunity in this, an opportunity for me to add value, an opportunity for me to build a skill.” So it turned out that there were these five situations that impact players tend to think differently than others. So first is like messy problems, they don’t fit neatly in anyone’s org box.

LW: Two is unclear roles, I think about every time I have lunch with one of my friends in the corporate world, there’s usually somewhere in the conversation, it gets to like, “Well, I’m on this team and I’m not sure who’s in charge, and I’m not really… And I need someone to clarify the roles for me,” and we find that most contributors are waiting for clarification like, “Okay, who’s really in charge, who has the authority here?” Whereas the impact players don’t wait for that clarification, when they see a leadership vacuum, they step up and lead. And they’re like, this is an opportunity to provide much needed leadership rather than waiting to be asked, and they very willingly lead. But what makes them, I think, so remarkable is their willingness to not always lead, to step back and say, “You know what? I’m going to lead, I’m going to provide this service to the group, and when I’m done, I’m going to step back and let somebody else lead, which…

BB: Big. That’s big.

LW: Like they’re flexing their leadership muscles, but they’re not making a land grab.

BB: Yeah, oh my God. And it’s such a mark of our research, what we would call grounded confidence, the ability to step up and lead, the ability to step back and make room for someone else to do it when it’s appropriate, it’s such a mark of confidence.

LW: It is. And it’s like that stepping back is this confidence, which is, I’m confident in my colleagues, I’m willing to follow their leadership as well, but I’m also confident that I will be given another chance to lead. The image I always like to get is the geese flying in V formation, and I did a little looking into this, and because the geese fly in this V formation where one bird takes a lead, breaks the wind, creates this easier path for the birds that follow, of course, when they tire, they fall back and another bird comes in, that this flock can fly 71% further than solo flight.

BB: Wow.

LW: And I think it’s the kind of leadership we need in modern organizations, it’s not like… I think the wheel of fortune used to have the saying, it was, “Once you buy a prize it’s yours to keep.” And I think there’s a lot of leaders who were raised on this logic of like, once you’re given a management job it’s yours to keep forever, like you’ve been appointed and anointed into leadership and so now you’re always the boss. We actually need organizations that are far more agile than that, where I could step up and lead, but I can also step back and follow others so that the whole organization can get further. So it’s this vacuum that they see as an opportunity. And the other one is like challenges, challenges you couldn’t have expected, sort of unreasonable challenges.

LW: Most people say, “Okay, I’m going to take ownership, but when it gets unreasonable, I’m going to hand it back up the chain.” Whereas I’m like, “Well, this is actually an opportunity, if I hold on to this… Yeah, it’s inconvenient, it’s hard, but if I don’t give it back up the chain, this is actually an opportunity to do things differently.” A lot of us seized this at the beginning of the pandemic, where it’s like, “Oh, there’s no rules, no one’s going to tell me how to like adjust…”

BB: Yeah, it’s right.

LW: And I’m like, “Okay, well, if no one’s going to tell me what to do and this is like an unreasonable obstacle, then I’m just going to find the right way to do this, I’m going to figure out a better way, I’m going to stay in charge of this project or piece of work, but this is an opportunity to innovate.” And it’s just what we saw over and over, where other people see threat. Like, “Oh, this is scary. This is uncertain.” They’re like, “Yeah, that’s true. But where’s the opportunity in this?” Which is what kind of pulls them into this uncertainty, as you’ve been teaching all of us, it’s demonstrating the courage to go into this uncomfortable place.

[music]

BB: Let me ask you this question. In the service of being an impact player, do impact players ever hear, “Hey, back off, sit down, do as you’re told.”

LW: Well, I can’t speak to every instance, but what I can speak to is how their managers talked about it. So I expected that when managers identify their impact players, this is a superstar, that some of them would have sharp elbows, a little rough around the edges. And one of the things that I was blown away with in these interviews is, to a person, not a single one of these impact players was a prima-donna, not a single one was a bully, not a single one was a bull in a china shop, they were team players as well. So this isn’t like your kind of prima-donna superstar like, comes in with swagger.

BB: Hot dog.

LW: Like “Man, I 10x everybody else’s code,” because it’s where they start, like the beginning is they don’t just do their job, they do the job that needs to be done. That’s one of them, the fifth big distinction is when times get really tough and everyone’s feeling like, “I have more work than I can humanly do,” they don’t just carry their weight, they find ways to make work light, and this was actually one of my favorite distinctions.

BB: Yeah, I love this. Say more.

LW: They make work easier for other people. So rather than like, “Hey, I’m a superstar and this is what I bring, and I’m a hot shot and this is what I need you all to do to clear a path for me,” they’re looking at, “How do I make work light for everyone?” Which starts by being easy to work with, low maintenance. We all know that there’s the workload and then there’s the phantom workload, which is drama, politics, difficult people. They are removing that phantom workload. Which is like, you know what? We’re all dealing with super hard work, let’s not make this any harder than it has to be. So they’re low maintenance themselves, they are easy to work with, they don’t create an extra tax and they’re looking at, how do I make work easier for everyone?

LW: And it’s not like, “Oh, I see that you’ve got a heavy workload, let me do your work for you,” it’s, “Let’s just not make this harder than it has to be and let’s keep the work environment kind of light, kind of fun, kind of funny,” and they’re just people who make hard work feel more joyous, or at least who don’t make it miserable. And so if you think about it, their orientation is, “How do I make myself useful and do the job that’s important?” They get things done all the way with the completion gene, they make work light for other people, these are people everyone wants on the team.

BB: Yeah.

LW: They’re not just superstars for their bosses, they’re kind of amazing colleagues to have around.

BB: Yeah, I’ve really got that sense. Let me ask you, I want to ask two questions before we get to the rapid fire, because there’s so much meat in this book. The first is, I’m thinking about what a lot of women, people of color, face in organizations where systemic racism, systemic bias is so real and prevalent, that how do you make work light and be the really fun person and step into… Let’s be totally honest, as a white woman, I can step up and say, “Let me take this. I’m going to try something new.” A black woman might be perceived as overly aggressive for doing that, how do we deal with real systemic bias in cultures in organizations, how does that affect impact players? Does that make sense? It’s a big issue.

LW: It’s a big issue and there’s so many different angles that we can come at this. Let me try to just address a couple. First of all, I want to tell two different stories about this, the first story is what I found in the data, when we looked, we kept all the demographics on this data and we did our analysis just to see, my research team and I we were cheering every time we did one of the analysis, we found the presence of these impact players evenly split across gender.

BB: Okay, good news.

LW: And we were thrilled. We found them evenly split across age ranges.

BB: Great.

LW: Maybe slightly skewed young, but it was not a significant thing, but we saw this nice age distribution and we saw from an ethnicity, race, we saw an even distribution there. So I’m like, “This is awesome. There are impact players everywhere, everyone can be an impact player.” Okay, then I start looking a little bit more closely, and I realize one of the dynamics is, it’s so easy for there to be missing impact players, people who are doing all the right things, but who go overlooked and this is… I address this throughout the book, that this is the cry and the call to managers, which is there are amazing people on your team who are making an impact and you don’t see it, and it might be the job that you’re working in, perhaps it’s really behind the scenes. It might be people who have been historically overlooked and taken for granted, not seen in the world, and this is the job of the manager to say, “You know what? There are people who could make an enormous contribution who are not being seen and not being heard right now, and how do I create an environment where they can contribute in bigger ways?” I think this is part of the job for leaders right now.

BB: Yeah.

LW: And to recognize that people come desperately wanting to contribute. Now, if you come from, perhaps a group where it’s harder to speak up, there are things that we have to do, like fundamentally, this is the job of a leader, is to create this environment, but where that has not been done for us, I think there’s a number of things that we can do to, as we step up, ensure that we’re getting permission to do it, like would it be helpful if… I’d be happy to take the lead on this. Would that be a useful contribution to make to the group? And continually to get permission. I found this as a woman in tech, there was a lot of times where I was pushing on the senior leaders and being pretty pushy, and I found that there were things I had to do to make them comfortable with me being so aggressive.

BB: That’s frustrating. But it’s life, I mean, it’s real.

LW: I do hope the book helps managers take more of that burden off of people, that is one of my hopes for the book, to realize, that is my job.

BB: It’s in there, and what I think is powerful is that impact players exist across age, across gender, across race and ethnicity, but how they’re acknowledged and seen is subjected to the bias of leaders and that’s their work to fix.

LW: And I should say in our sample, that was absolutely the case. And our research was done in some of the most well-run companies interviewing really well-run leaders, so these are very hospitable environments for contribution.

BB: Right.

LW: And I know that this is not the case for everyone, that some people are going to find this harder to do, my hope is that the book offers some ways for people to show up big and to play big, and I don’t mean to take over and to play at anyone’s expense, but to be able to make a full, whole-hearted, whole-minded contribution.

BB: I love what you just said. I think it’s so powerful what you just said and you said it in passing, but it’s so… We don’t talk about this, and it’s just such the heart and soul of your work, and I think with Multipliers too, which is, are you an organization that is open to contribution? There’s so much pissing and moaning about the lack of contribution, but there’s a big question that leaders have to ask themselves, which is, “Am I open to contribution?” Because being open to contribution is letting go of some control.

LW: And it’s seeing invisible desire. A lot of managers are like, “My people don’t want to step up, they don’t want to take responsibility. I asked questions and they didn’t respond.” I’m like, “Well, first of all, you might not be doing it really well, it takes… ” There’s an art form to being a good leader, but it also takes us seeing this invisible desire people have to contribute and… Again, this is something I learned at a young age where I’m like, oh, my dad is not trying to be hurtful. He has been hurt and what is he wanting to do? Like, oh, he has such a hard time expressing love, but I’m sure he wants to, I’m sure that’s something he would do if he could. One of the questions that I use when I’m sort of working with a very difficult leader or someone who’s really having a hard time, I ask myself, “I wonder who did this to them? Who made it hard for them to be vulnerable? Who made it so that they had to have all the right answers?” And when we have people on our team who appear to be undercontributing or who are under contributing, I find it helpful to sit back and say, “What did this to them? What made them afraid to volunteer to take the lead? What were their experiences, what has life taught them to hold back?”

LW: Those are learned barriers and those are imposed barriers, so like, “Well, what if I could help remove some of those barriers, then maybe they would have a pathway for contributing. Something caused this to happen. It is not our natural state, laziness, and kind of getting off easy is not our natural state, and it’s actually painful for us.

BB: I agree 100%. And I think, going back to our conversation about race and gender, ethnicity, age, sexual identification, orientation, I also think when we ask what happened or who did this, I think we have to look at systems that are in place too, and am I engaging in behaviors every day that are confirming a lack of safety. I’ve been thinking about Amy Edmondson’s work when I was reading this, how psychological safety… Boy, if we could get people safe, I think we’d have impact players just all over the place, maybe some don’t have to wait for safety, but for others safety is not just an academic issue, it’s a real safety, it’s physical safety, job security.

LW: Brené, I agree, and I would even push it further, I think we have to have safety to contribute, and some people already have it, like they show up feeling safe, and maybe those are people who we’ve categorized as having ordinary privilege. Life has made it easy for you to feel safe so that you can take on these big stretch, for other people, that safety has to be established thoughtfully, carefully. And one of my observations, it was a long time after I had written Multipliersand I kind of stepped back from your work and then you’re like, “Oh, I now see it, and I see it more clearly than I did when I was writing that darn book, is, you know what the best leaders do is they create an equilibrium between two forces and the two forces are safety and stretch.”

BB: Yes!

LW: Because, what is it like when we work for someone who’s all stretch, no safety?

BB: Impossible. Scary.

LW: It’s scary and it’s what people who have been barred by systemic bias and racism or sexism, like that’s often what they experience, is I don’t feel safe to raise my hand to sign up, but on the other hand, what’s it like to work for someone who’s all safety, no stretch?

BB: Terrible, awful. Boring and lifeless.

LW: Lifeless, soul-sucking. And that is the job of the leader. And if you want to build a team of impact players or just to have a team of healthy whole people, create safety, but don’t leave it there, stretch people, challenge people, invite people to do hard things, and then create the next level of safety and it’s like almost in not just the long arc of your job as a leader, but in any meeting, it’s like, “How do I create equal measures of safety and stretch?”

BB: That’s beautiful. That’s really good.

LW: Or as a parent. That’s kind of our job too.

BB: Oh no, it is for sure. And I always… I’m always leery about parenting and leadership because I hated the thought of infantilizing work but it is absolutely the job of a parent to create safety and stretch in equal measures. Yeah, and we see the ramifications of doing one without the other. Alright, you ready for the rapid fire?

LW: I don’t know if I’m ready, but let’s do it.

BB: Oh, I think you’re so ready. You ready? Alright, fill in the blank for me. Vulnerability is…

LW: Telling it like it is, speaking the truth.

BB: What’s something that people often get wrong about you?

LW: Oh, that my work is easy for me, that it’s not really actually hard under the surface.

BB: What’s a piece of leadership advice that you’ve been given that’s so remarkable that you need to share it with us, or so crappy that you need to warn us?

LW: Oh, I got the crappiest leadership advice, my first job as a leader, my boss said, “Liz, your job is to do everything that is important, everything that is new, and everything that is hard, and your team does the rest.” I’m like, “Okay.” So I took on all the new important hard stuff. And I’m like a super star and everyone else is like, “Hey, put me in coach.” And I realized it was the worst possible advice.

BB: God, that’s bad advice.

LW: It was bad advice, I was starving my team of learning opportunities and I was like hogging the glory with this advice, I kind of figured out it’s actually the wrong way, it’s like your job is to feed your team a steady diet of challenge. And challenge is, you do the stuff that’s new, important, and hard.

BB: So good. What is your best leadership quality?

LW: Well, okay, I’m trying to think if I have good leadership qualities, I have a high bar on this. Wow, this is a hard question. I think my best leadership quality is that I invite people to do hard things, I’ve heard people say this about me, like with Liz, I don’t steal the important new hard stuff, I’d like really give people real challenge, and I think I also give people a lot of choice like, “Hey, here’s the work, what part of this do you feel like you can contribute to?”

BB: I love it.

LW: I do that well.

BB: What’s the hard leadership lesson that the universe just keeps putting in front of you and you have to keep learning it, re-learning it, unlearning it, what’s the thing?

LW: Oh, this is… It’s a leadership lesson, it’s a life lesson is, things that are easy for you aren’t necessarily easy for other people. Oh man, it’s so hard for me to see like, oh, just because I’m not struggling with it doesn’t mean other people aren’t struggling with this, and sometimes just the slightest bit of flippant like, “This isn’t hard” destroys someone.

BB: Geez. Yeah.

LW: Yeah, I have destroyed a couple of people’s confidence with that.

BB: Yeah.

LW: I’m not proud of it.

BB: I’ve seen it go both ways. I’ve been the sides of it, I’ve done the destroying, I’ve been destroyed confidence-wise because of that. What’s one thing that you’re really excited about right now?

LW: I’m excited about Bingo in congressional hearings. Last week, I was invited to… I cannot tell you how excited I am about Bingo. I think this might be my sole contribution to the world. I was invited to testify in a congressional hearing on the modernization of Congress, and they’re particularly looking at how do we increase civility and collaboration and positive peer-based leadership in congressional settings and in congressional hearings and they ask, “Well, what can congressional leaders do, so that these sub-committees, these working committees, they actually demonstrate more civility and collaboration, and I was like, “Well, here’s a whole bunch of things I could tell you from the world of studying great leaders and collaboration.” But if it were me, I would just open these up to middle school classes because there is no more critical discerning audience than middle school kids and don’t just let them observe because people change their behavior when they’re being observed.

BB: For sure, the Westinghouse effect. Absolutely.

LW: Absolutely. I’ve seen this in the business world, but give those eighth grade or middle school students a Bingo sheet with all the behavior you want to see happen and let them just play Bingo watching congressional hearings, like looking for demonstrations of civility, listening, curiosity, vulnerability, perspective-taking, like, let the kids play bingo, that’ll probably change behavior, and so I actually made that recommendation to the sub-committees and I think it’s actually, if they do anything, it might just be eighth grade Bingo during congressional hearings.

BB: Oh my God, will you report back? That’s amazing.

LW: But I don’t know.

BB: I was expecting something I could say, fairly I was not expecting that, and it’s amazing, that’s funny.

LW: I was not expecting it either.

BB: Yeah, I love it. Alright, we asked you for five songs you couldn’t live without for your mini-mix tape on Spotify, here’s what you gave us, “Beautiful Day” by U2, “I Lived” by One Republic, “Waves” by Dean Lewis, “September” by Earth, Wind & Fire and “Come Thou Fount” written by Robert Robinson and performed by a variety of choirs and artists. In one sentence, what does this mini mixtape say about you, Liz Wiseman?

LW: I think it’s about seeing beauty and living fully and learning how to reclaim the sense of awe and wonder and gratitude and connection with the world. It’s like we have it, we lose it, and we have to reclaim it.

BB: Beautiful, thank you so much for being on Dare to Lead. This was just such a great conversation, and the book is Impact Players: How to Take the Lead, Play Bigger, and Multiply Your Impact, and it is going to be out on October 19th. Congratulations on the new book.

LW: Oh, thank you. And Brené, I just love talking to you and thank you for your work. And if I could just say something as we close, I think, as I thought about why have you been impactful in the world, I think you see people’s pain, like this gap between what they want to be able to do and where they are, and then you bring this wholeheartedness to it, but here’s why I think your work has had such impact is that you are doing it for the whole, not for just one person, but for the whole community. And I think it’s powerful. So thank you.

BB: Thank you. That means a lot to me. I appreciate it. Thank you.

[music]

BB: Man, I learned a lot from this conversation. It was good, right, Barrett?

Barrett: It was so good. I had five pages of notes.

LW: Yeah. It was a note-taker.

Barrett: Yeah.

BB: Yeah, it was good. And you can find Liz’s new book, Impact Players, wherever you like to buy books. We love our Indy bookstores. We will post a link to it on our Dare to Lead episode page on brenebrown.com. You can find out more about Liz’s research at impactplayersbook.com. She’s on LinkedIn and Twitter @LizWiseman, and we’ll have all those links on the episode page. As usual, we really, really deeply appreciate you joining us on Spotify for both Dare to Leadand for Unlocking Us. You’re the reason why we do this. So without this community of awkward, brave, and kind listeners, leaders, we would not be doing the work. So thank you, and I’ll see you next time. Stay awkward, brave and kind.

[music]

BB: The Dare to Lead Podcast is a Spotify original from Parcast, it’s hosted by me, Brené Brown, produced by Max Cutler, Kristen Acevedo, Carleigh Madden and Tristan McNeil. And by Weird Lucy Productions. Sound design by Tristan McNeil and the music is by The Suffers.

[music]

© 2021 Brené Brown Education and Research Group, LLC. All rights reserved.