Brené Brown: Hi, everyone. I’m Brené Brown, and this is Dare to Lead. Before we jump into this episode, I want to tell you about a very special event that we have coming up. Atlas of the Heart is here. Oh my God, I cannot even actually believe it happened. It’s its own little miracle, I have to say. We’re not doing a traditional book tour because of pandemic and COVID safety reasons, but we are launching the book with a virtual event on Thursday, December 2nd at 8:00 PM Eastern Standard Time. We’re partnering with 150 independent bookstores within the US and Canada to bring you the event. Guess who’s interviewing me? This is just like a little miracle, you know her from the Dare to Lead podcast and hopefully her book, The Art of Gathering, Priya Parker.

BB: And so, it’s going to be the two of us and we’re going to go through Atlas and she’s going to ask me really hard questions, I’ve already anticipated this, so I’m re-reading the book because I think maybe it’s like labor, I blocked it. I think it’s going to be a lot of fun. You can find out all the details, including the link to register on the podcast page for this episode, and I hope you’ll join us. It’s going to be, I think, an important evening, and I think we’ll talk about things that matter in our lives. The virtual event is only available in the US and Canada, but if you’re not able to attend from where you are, we do have a special Atlas of the Heart podcast episode, actually a couple of the podcast episodes planned, so that we can all dive into the work together and explore, by bringing the sisters Ashley and Barrett will be in the podcast house.

BB: Okay, on today’s podcast. So I just did a podcast with Dr. Laurie Santos, she’s a professor of Psychology and the head of Silliman Residential College at Yale University. She’s also the host of the popular podcast, The Happiness Lab. So I just did a podcast with her that’s going to release on her podcast in January, on Atlas of the Heart. And the second we hung up from the podcast, I looked at Barrett and Laura and I was like, “Oh my God, I’ve got to talk to her. I want to talk to her about what’s going on with college students these days. I’m seeing so much struggle. I want to talk to her about the fact that so many of us are going to be back at work in person after the New Year.” And so we invited her and she said “Yes,” and we jumped on and did this podcast, and I can’t even believe how great it was. She teaches a class at Yale that is the most popular course in 300 years at Yale. It’s a course on flourishing, the good life, really empirically-based approaches to making our lives better, and she shares a lot of that with us on the podcast. I’m really excited that y’all are here. PS, I cannot believe that Atlas comes out tomorrow. Stay tuned. We’re going to jump in.

BB: Okay, before we get into the podcast with Laurie, let me tell you a little bit about her. So Dr. Laurie Santos is the Chandrika Ranjan Tandon Professor of Psychology and the Head of Silliman College at Yale University. She’s an expert on human cognition and the cognitive biases that impede better choices. We talk a lot about this, about how our brain while well-meaning, really is not helpful sometimes. Her new course, Psychology and the Good Life teaches students how the science of psychology can provide important hints about how to make wiser choices and live a life that’s happier and more fulfilling. Her course recently became Yale’s most popular course in over 300 years, and almost one out of every four students at Yale has enrolled in it. This course has been featured all over the place, New York Times, NBC Nightly News, The Today Show, GQ magazine, O magazine. Laurie is the winner of numerous awards for both her science and teaching, and she was recently voted as one of Popular Science‘s magazine’s, “Brilliant 10 Young Minds” and named in Time magazine as a “Leading Campus Celebrity.” Her podcast, The Happiness Lab, has over 50 million downloads. Let’s jump in. Dr. Laurie Santos, I’m so excited to have you on Dare to Lead. Thank you.

Laurie Santos: Thanks so much for having me. This is a joy.

BB: Yeah, and I’ll just tell you that I just recorded a podcast with Laurie and the millisecond we got off, I turned to my team and I was like, “Oh no, no, I have 7,000 questions for her, we’re going to do a ton of podcasts with her over the next year,” and they’re like, “Starting when?” I’m like, “Can you call her now? Can we call… ” [laughter] So, thank you for doing this.

LS: Yeah, no, I was really… I had the same experience, but I had just invited you on my podcast, so it would be weird for me to immediately call you back and be like, “Can we do it again? Like, same thing, next time?”

BB: [laughter] I would have said “Yes!” Okay, so here’s what I want to talk to you about. There’s so many things I want to talk to you about. I want to talk today about your thoughts on gathering again. I work with a number of companies, everyone has a re-gathering, new gathering plan for the new year. I want to hear what you think. I want to hear what you caution us about, I want to hear what you’re excited about. Is that okay?

LS: Yeah, no, totally, this is perfect. Yeah, I think… Lots to say here, right?

BB: But wait, before we start, I want to… Before we start, I want to do something else before we start. I want to know your story, all the way back to baby Laurie Santos.

LS: [chuckle] Yeah, well, the stories, I was always an annoyingly curious kid, I think especially annoyingly curious about humans and human behavior. I was the kid that always wound up in the adult room where the adults were talking. My mom would be like, “Go, go play with the kids, go play with the kids.” But I think it was because even from a really young age, I was really fascinated with humans and human behavior. That early on got translated into a love of animals and just a kind of fascination with animals. I think animals are kind of so close to humans but not exactly human, and so when I first got started academically, realizing there was this field where you could study people and how people work and how they make decisions, yeah, I was super drawn to psychology. But my first research, it was in fact with animals, with studying non-human animals. I worked with monkeys and was really interested in how monkeys think. And I caught that bug in part because I just had a charismatic professor who was doing this work, but then he had this opportunity to go to this cool field site in Puerto Rico where I headed down and got to study these super interesting free-ranging monkeys, these are rhesus macaque monkeys, huge, 200-monkey social groups, and just all this kind of infighting and drama, and just watching…

BB: Let me stop you here. How big is a monkey?

LS: A monkey, so a rhesus monkey is like a kind of small dog, large cat. [chuckle] But they could take you out pretty bad, they have very, very sharp canines and they fight a lot. So, when you first get down there, you’re watching them like, “Oh my gosh, they’re so interesting and doing this cool stuff,” and then some sort of fight breaks out and then you’re like, “Oh, okay,” [chuckle] and you find yourself standing… You were like right up there watching them, but then you find yourself standing much further back. And so…

BB: So, German shepherd size?

LS: No, no, no, more like fat Pomeranian sized. Yeah.

[chuckle]

BB: Okay.

LS: Yeah.

BB: And so you go to Puerto Rico. Had you ever been around primates before?

LS: Not really. This was really my first experience. I mean, to be totally honest, when my professor put up the pictures of his field site, I went to school in Boston, it was just starting to get cold, this is my sophomore year, and he puts up these pictures and it was like palm trees and beaches, and this island… Literally, it’s an island off the coast of Puerto Rico, filled with monkeys. So it was like palm trees, beaches and monkeys running around, and I was like, “How do you not do that if you have the opportunity to do that?” But really, it’s this really incredible field site called Cayo Santiago, and it’s home to about 1,000 free-ranging monkeys. They have been studied since the 1930s, so they’re totally habituated to humans, they kind of… The lore is that they treat us like walking trees. They don’t want to get stepped on, but other than that, they don’t care too much about us. And you can just go down there and observe them and pay attention to their behavior. We can even do little mini experiments to test what they know. But mostly for me, what was fascinating was just seeing how similar they are but how different.

LS: There’s a lot of monkey drama, the monkeys care about who they’re going to mate with and how their kids are doing and getting up in the world, and they navigate all of that without smartphones or language or an internet or just these things. And so that was super cool. So, most of my career, I was what’s called a comparative cognition researcher, I kind of studied how animals think. And I got more interested in the kind of stuff you do when as an academic, now a professor at Yale, I took on this new role on campus where I became a head of college. You know, so for awhile I was just doing my research thing.

LS: And when I took on this role as a head of college, I wound up living on campus with students, so hanging out with them in the dining hall and in their coffee shop. I went from being a professor that was up in the front of the classroom teaching about animal psychology to living in the trenches with students, and it was jarring. I did not expect to see the level of mental health crisis among today’s college students as I saw. So many students just reporting feeling depressed, feeling anxious, I mean like extreme… Even suicidal ideation, panic attacks, but even the light mental health crises were like… I’d ask a student, “How’s it going?” And they’d be like, “I just got to get to mid-terms, if I could only get to end of the week, if I could only get to break.”

LS: And it was like, you’re fast forwarding this really precious four years that you have, and you’re so stressed. And so that was when I kind of re-trained in positive psychology, some work, just trying to figure out, what are some evidence-based tips that we can give students so that they can have some strategies to navigate the stress that they find themselves in in this place? And so that was kind of how I got interested in the science of well-being. I taught this big class, it totally went viral, I started a podcast, and that’s my whole life story, from monkeys to podcast.

BB: Where did you grow up?

LS: I grew up in New Bedford, Massachusetts, which if you remember your Moby Dick, was the town that Moby Dick was set in. So it was a huge Massachusetts city for whaling, now it’s much more working class. I went to a big urban public high school, and so… Yeah.

BB: Wow.

LS: I used to have a very thick Boston accent, but I lost it in part because my first year of college, my roommate was from New Orleans, and she had an incredibly thick New Orleans accent, and I had this really thick Boston accent and somehow we converged to the point that… Back in the day, when there’s a land line in your college dorm room, people would call and they couldn’t tell us apart, and I was like, “What has happened to our voices?” But yeah.

BB: You become the Borg, like yeah, I’ve got…

LS: You become the Borg, yeah.

BB: The Borg, yeah. God, I have so many questions already just from the story. For those… And myself included, because when you say that you are the head of a college at Yale… I went to UT. To me, that’s like Hogwarts.

LS: Yeah, it’s full on Hogwarts. Yeah, it’s really like… Yale likes to pretend it’s Hogwarts, like our dining hall looks like Hogwarts and our building looks like Hogwarts, but the thing that’s most Hogwarts-y is there is these colleges within a college. So just like in Harry Potter’s Hogwarts, there’s Gryffindor and Slytherin, here at Yale, there’s like the Silliman College, which I’m head of, and Timothy Dwight and JE. So they’re like these… They’re functionally dorms, but they’re these kind of mini communities within a community. Just like in Hogwarts they have their own identity, their own resources, their own staff. So, I’m like Professor McGonagall. I actually forget my Harry Potter, but I’m like a professor who’s living in this college with students and interacting with them.

BB: What prompted you to do that? Because that’s different than being a faculty member. As a faculty member, I can tell you, for 20 something years, I’ve never lived with students.

LS: Yeah, I think because of my research with the monkeys, attracts… Just like I got attracted to it when I was a college student, it attracted lots of college students, so I had tons and tons of different mentees who I worked with in my lab. I was like what universities call a Director of Undergraduate Studies where I met with students to help them pick their majors and things, so I’d done a lot of Student Services. I would have honestly told you before I became a head of college, like, “Oh yeah, I know college student life, I know what their stresses are, I know what the pain points are.” I would have really felt that I knew this strongly, but I feel like I didn’t see any of it until I was really in the trenches with them.

BB: Okay, so what have you learned?

LS: Oh my gosh, so many things. I mean, first, I think young people are struggling a lot more than people think. When I talk to people who have kids in high school, kids in middle school, I’ll ask, “Do you know what’s going on? Do you know how many of your kid’s friends are depressed or feeling anxious?” Because I think people don’t realize the crisis is as dire as it is. Because I think sometimes, I tell the story and people think like, “Oh, those Yale kids, they’re so Type A, Ivy leaguers, pushing themselves and pushing themselves.” But this is really a national situation. Right now, nationally, the stats are that over 40% of college students report being too depressed to function most days, so more than 40%.

LS: More than 60% say they’re overwhelmingly anxious, more than 80% say that they constantly feel burned out and overwhelmed by what they have to do, and more than one in ten says that they’ve seriously considered suicide in the last year. Like, this is like a crisis, and so when I saw this, I realized… I look at my classroom of 100 kids and I’m like, “Okay, well, in a hundred kids, 40 are too depressed to function, more than 60 say they’re overwhelmed and anxious,” and I was like, “Wait, these students aren’t learning in the same way we hope they are learning in some Ivy League institution, they’re just trying to get by.” And it made me realize that if we’re just doing the normal college thing, if we’re not teaching them strategies to navigate this, we’re kind of not meeting our mission.

BB: Yeah, it’s funny, I just wrapped teaching an MBA course at UT, and it’s the first time I had taught, and I’ve never taught undergrad, interestingly, but it’s 100 students and we always start even the online courses, we did some online, some in-person, with a two-word check-in, an emotion words. And other than hungry, I think number one report in is “overwhelmed,” “exhausted,” “holding on,” “untethered,” yeah, yeah.

LS: Yeah, “I’m stressed, I’m stressed.” “How are you doing?” “I’m dying.” Yeah, yeah. I shouldn’t even have to say it, but like, that shouldn’t be that way. Like, that is really sad. That is not what college should be, it’s not optimal for learning, it’s not optimal for the tail end of their brain development, it’s not optimal for them forming the social relationships that are going to be the friendships that stick with them through life. I think we really need to seriously consider the kind of culture that these students are living in and what ways that we can deal with it. Just give them some intervention so that we can help them fix this.

BB: What percentage of it do you think is environmental, and what percentage is… I know it’s messy and mitigating, but what is the world we live in and what is the university experience?

LS: Yeah, yeah, I think it’s both, and I think both of those things have changed a lot since I was an undergrad. People who are listening can’t see me, but I wasn’t an undergrad that long ago. [chuckle] Wasn’t so long, right? But in the last 20 years, I think things have changed a lot. The world has changed a lot. We’re living with political polarization, a 24/7 news cycle where you’re just hit with anxiety-provoking information all the time, not to mention right now we’re in the midst of this COVID-19 pandemic, that’s kind of new and awful. But I also think university life has changed in these interesting ways too. Back in the day, it was not the most inclusive spot, Yale University. If you were to rewind back into the 1800s or early 1900s, it was a bunch of, honestly, cisgender white guys from a few very elite high schools. Now, in theory, literally anyone who tries hard enough and puts enough work in and has the right smarts can get into Yale. But I think the fact that the spoils of the war are so high, people perceive like, “Oh my gosh, if you get into Yale… ” I watch high school students killing themselves to get into Yale and other places like it, and that means that a lot of the mental health issues I’m seeing in my students are driven by academic stress.

LS: All those stats I was quoting, they’re from a National College Health Survey that goes out every three years, and they ask students for all these things, “How anxious are you? How stressed are you and how depressed?” But then they also ask “Why? What are the causes? Is it financial stress or is it social stress?” The highest self-reported cause is academic stress. The students perceive their workload as causing this stuff, and that feels new. Even when I was in college, it was tough and you had to worry about your stuff, but not worry to the point that you were burnt out and overwhelmed all the time. And so I really do think we need to think about the structure of universities and how we can change this, but I think it goes to how we admit them, what we as a culture think our goals are for education. There’s some big sweeping structural changes we need there too.

BB: Yeah, and I would drop it back all the way to high school, probably. Because I have to say, it’s interesting, we’re both faculty members, we both have PhDs, that was just never my experience.

LS: Me either. Yeah, no, me either.

BB: Yeah, even when I was thrown into multivariate linear statistics, and I was quasi-confident what mean, mode and median meant starting, even when I was definitely over my head, it never felt life-threatening or even mental health threatening. It felt like, “Shit, man. This is a hard class.” And it’s interesting, I was so blown away by these MBA students at UT. For our final class, they were in teams, six or seven, and they did Pecha Kucha presentations on any topic related to what we were teaching. I was teaching Dare to Lead, so courage-building, empathy, vulnerability as it relates to organizational performance and DEI work. And every one of the presentations was about combating loneliness in a competitive environment, overwhelm and identity and representation. Like, every one of the presentations, they were filling in gaps of what they weren’t getting from us.

LS: Yeah, yeah, there is this other interesting question which is like, why are our 20 year olds who are academically gifted enough that they could get into an Ivy League institution, showing up with questions about “how do they make friends, how do they navigate conflict with a roommate? I can’t”… In my role as head of college, I get called in a lot. Like, “My roommate get’s up too early and their alarm goes off.” It’s like, “Well, did you have a conversation with them?” “No, no.” And it’s like…

BB: Hell no.

LS: And cases honestly where the intervention oftentimes, sadly, is like their parents want to have this conversation, so sometimes it’s not even that the students will come to me as their head of college, their parents will come to me and say, “Hey, my students having this problem with their roommates.” And so I think we’ve lost, first of all, just being in touch with what’s going on in ourselves, being in touch with what’s going on in our bodies and our stress levels, there’s a kind of toxic productivity in the students of today that I think was different than in our generation and is one that’s activating their fight or flight system consistently in ways that I think make them worse off health-wise, that make them struggle socially.

LS: I also think that this is just a time when students need more social skills than they’re really getting. There were so many shocks when I first became a head of college, but one of the ones that was particularly shocking, was like one of the first times I went into the dining hall… This is like pre-COVID, right? Walk into the dining hall. I remember our dining hall on campus was like the loudest. People are talking, and it’s like a hum

BB: Yeah, Yeah.

LS: It’s not so much that our dining hall is quiet, but these days when you walk in, you see students working, often with these big Bose headphones on with their laptop out and they’re just like, they’re just diving in and they’re not talking to each other. And so this space, that was the space where I most connected with the humans I genuinely love, even today, the people I see as my lifer friends, were in those dining halls. And I’m like, “Wow, these students have this three times a day and they’re not harnessing it to make the connections, at least in the same way that we did before.” Again, it’s not to say the students don’t chat with each other in the dining hall, it just it feels different.

LS: And this is also mapped on to by the fact that, again, nationally, if you look around two-thirds of students self-report being very lonely most of the time, college students, which I’m like, “When else in your life are you going to have a bunch of interesting smart people your age, literally living down the hall from you and…”

BB: It’s a proximity, the proximity of friendship in college is never replicated again in our lives.

LS: Yeah, and so if they’re struggling now, what’s going to happen when they’re in their thirties, what’s going to happen when they pop off to some city that gives them a high salary, but they’ve never been there before, these are struggles that I think we need to help give our students solutions to, because they don’t have them right now.

BB: I talk to my daughter a lot. She’s 22, graduate school, studying emotion, and she said, “You know, I think we’re on the verge of anxiety and fear all the time,” and I said, “Tell me.” She goes, “It’s hard not to be when you’re raised on active shooter drills and hostage drills at school, and you go home and parents are screaming and not talking to each other, and the news is always on,” and your course that you teach, the most popular course at Yale in 300 years. Is what I read here, is that right?

LS: Yeah. Totally right. Shocking, but totally right.

BB: Yeah. What do you teach students?

LS: Yeah, so it’s called Psychology and the Good Life, so I just want to suck students in with the sexiness of the title. The good life, but the whole course is about evidence-based strategy students can use to feel better. It starts with the idea that science shows us that we can change. All those statistics, I just said, they don’t have to be that way if we could find strategies to navigate those negative emotions, find ways to get in more positive emotion in our life, find ways to get in more social connection and so on, and the research really does promote, you can grow and change if you want to. The problem though, and this is a big theme of the course, is that it’s hard because our minds lie to us. I mean, you know this quite well.

BB: Oh God. Yes.

LS: Like our mind say, “Oh, negative emotion, run away,” our minds say tons and tons of thoughts every day that I would never tell a good friend of mine about myself about how crappy I am and how worthy I am and blah, blah, blah. Our minds lie to us about the kinds of things we’re going to enjoy, I think my mind thinks like, Oh, and I’ve had an exhausting day, I want to plop down and just watch Netflix and never get off the couch, but my mind doesn’t say, “Hey, why don’t you go for a hard workout, or why don’t you call a friend you haven’t talked to in a long time.” The point is that we have intuitions about the kinds of things we need to do to promote our mental health, and the kinds of things we need to do to live a happy life.

LS: But oftentimes, those intuitions are wrong, they’re like, change your circumstances, get lots of money, succeed, succeed, succeed at all costs, like toxic productivity, that will feel great. And in practice, those intuitions are leading us astray. It’s not that we’re not putting work in to becoming happier, we’re putting in the work, we’re just doing it wrong.

BB: The wrong work. Yeah.

LS: And so the class is really about like, okay, what is the right work, how do you navigate emotions, how do you deal with your thoughts, what are just simple strategies from this field, a positive psychology that you can do to kind of fill your little leaky happiness tire as we call it. What are just simple things you can do, mindsets you can take, behaviors you can engage in that are going to make you feel better, not worse. And so, yeah, so students learn all these stuff…

BB: Give me a couple of sticky ones that the students really love.

LS: Well, the biggest one that every time I present this, I have a huge line of students who want to fight with me is what doesn’t work, which is money. These are these Yale students who’ve been taught like, get into a good college so you can get a good job, and I present this work to saying, Yeah, if you’re below the poverty line or if you really are in food insecurity, can’t put a roof over your head. Yeah, more money is going to make you happy, but at a certain point, it’s just not going to matter that much, or it’s definitely not going to matter that much as equal amounts of your time and effort could get you if you invested in, say, social connection or doing good things for others or doing meaningful pursuits that weren’t just like work, work, work. And I’ll get this huge line of students like…

BB: Oh God, yeah.

LS: But what if I invest it differently? What if my income bracket is like, I grew up in a more lower income, and it’s like they kind of just want to fight with you. Another one that I get a lot on is when I tell them the work about sleep, there’s so much evidence that sleep matters, obviously from mental health shouldn’t be shocking, like brain is connected to the body, mind is connected to what is happening physically, but yeah, they see this and they think, “Well, how could I possibly sleep because I have to study, study, study so I can get As. So I can get the perfect job, that’s the route to happiness.” And it is like I am watching them get four to five hours of sleep at night, that’s actually on average, what a lot of college students self-report, there’s a variance, but… And then I show them data about what your mood levels look like if you get four hours of sleep at night, and I say, I actually think we could solve most of the college student mental health crisis if you guys slept more and they don’t like that.

BB: Yeah, and I have to tell you that their response to the sleep thing is almost like it’s so disproportionate to the proposition, people are like, “You can’t take away hours from me.”

LS: Yes, yeah.

BB: I’ve got to work. My husband’s a pediatrician, and we talk about sleep all the time, because we have really strict sleep rules in our house for all of us. I have a 16-year-old son who’s a sophomore in high school, and I’ve got my 22-year-old Ellen, but it’s probably some of the biggest fights we get into, we’re not negotiating this with you, you’re not going to bed at midnight and waking up at five for an extra practice, but what’s really funny is he came home one day, probably a decade ago, and he said, “You know what’s really hard for me to explain to parents is that about 60% of behavioral issues can be solved with sleep, starting with toddlers.”

LS: Yes, yes.

BB: It’s just, we have to recover, but man, people take that shit personally, and the money thing too, these are MBA students at homes, at UT, and they’re all interviewing right now for their jobs, and I always say to them, “Five minutes of telling someone where you got a job and five years of working in that job. I need you to really think about it.” And now I’m to the point where I just say, “Take the job because you’re going to take the job anyway, but check in with yourself in a year.”

LS: Yeah, and here are some strategies you can use while you are in that job, because it’s probably going to make you pretty miserable.

BB: That’s right. Yeah.

LS: Yeah, I think one of the things that really breaks my heart about Yale students is that I think because they perceive as though they’ve achieved so much, they’ve gotten into an Ivy League school. It winds up being the sort of strange set of handcuffs about what they think they can do with the rest of their life. They might want to be an artist or a teacher or a police officer, but they feel like they’re not supposed to do that because now they have this opportunity to go be an MBA or do something that makes a certain amount of money, and I watch them picking careers that take them away from their family, away from their values because of a paycheck, and I’m like, I know the data that says that, again, you need a job and you need to put food on the table, but after a certain point, the extra zeros aren’t going to matter, and it’s just sad because I think this is the beauty of the positive psychology work, is that my read is like they’re just strategies you can use to feel better. To navigate negative emotion smoothly, so they don’t destroy you, to engage in behaviors that actually boost you up like social connection, doing for others, to develop mindsets that just feel better, gratitude, presence, all the stuff we could do it, but we have to do it and it takes some work.

LS: But one of the biggest features of the work is realizing that the intuitions we have are leading us astray. You’ve got to confront those first. You talk about this all through your new book, are we talking about your new book? I think…

BB: Oh, we can for sure. Yeah.

LS: Your new book, which as I interviewed you about on my podcast, is exactly this. So many beautiful, interesting, diverse emotions that you talk about in the Atlas and a lot of them, the intuition is like, any of the ones that feel undesirable, if those crop up, run away, shut them down, suppress them, force it, that’s how we live a happy life and I don’t know, keep going in the face… Like no. Like, brain, stupid, stupid, strategy, can we come up with something else?

BB: Okay, let’s shift gears for a minute because I want to get to this. Tell me your thoughts. There seems to be a big return planned, at least in the US, when we talk about the US workforce, there seems to be a big plan to return after January 2022. Have you seen this too?

LS: Yeah, yeah, I think everywhere is like preparing everyone now, you and I are having this conversation in November of 2021, and it’s like we’re starting soon everyone, we’re coming back and so… Yeah, and I think my first reaction to this is, on the one hand, this is great news, the number one thing that positive psychology work shows is important for living a happier life is social connection. And they don’t mean like hanging out with your best friend on vacation all the time, they mean literally just interacting with other humans. There’s evidence, for example, that the very happiest people, literally spend more time around other people. And I think we inadvertently, this pandemic has caused us to do an unnatural experiment where all of us just shut most of that off, completely shut most of that off for 20 months. The simple interactions we get chatting with the barista at the coffee shop when you grab your latte on the way to work, you’re talking to people at the water cooler, walking by people in an elevator, a lot of us have lost those simple interactions, and we’re blind to how much they matter for our flourishing. There’s some wonderful work by the University of Chicago Professor Nick Epley, where he forces people to talk to more strangers, like talk to somebody on your commute to work.

LS: And people’s predictions are not just like, that’s not going to matter for my happiness when people also predict being around these strangers are going to be worse for my happiness, and talking to them is going to be actively bad, but what he finds is that when people engage in it, it feels really good. It’s just one of the things that we do to fill up our happiness tank, and so many of us just haven’t had the opportunity to do that, some of us I think in the worst of the pandemic, if you lived alone, man, you could do it over some screen, but not in the real life way that we were built as primates to do. So all that goes to say, I think flourishing-wise, there’s lots of reasons to suspect that the return to work, even just in terms of social connection is going to be overall good for our happiness, but we are not creatures that naturally gravitate towards things that are good for our happiness, and we definitely don’t like change and for better or for worse we’ve gotten used to what things were like in the pandemic where we’re at home, often not wearing adult shoes or adult pants being really honest. In Zoom we’re…

BB: Yeah, we got toddler stretchys on.

LS: A lot of elastic waist are happening. So I think that change feels scary, and I think for some of us, we’re feeling like kind of out of practice with other humans, I feel like… I’m seeing this in my department now, we’re finally getting together for live events, and I feel like we’re all like, I don’t know how to talk at a like a normal dinner party anymore, it’s like or people are like talking so much because they’re kind of nervously excited. I think it’s like when you go back to school when you’re a kid, I feel like September is exciting, but it’s also a little nerve wrecking, and I think we’re all doing a collective go back to school, and not just after a few summer months, but after a long time.

LS: And because of that, I think we need to adopt a certain attitude when we’re doing an attitude of optimism, I think the science backs up, it’s probably going to be better than you think, but also an attitude of self-compassion and some grace. We all just took this hiatus and we’re out of practice, and that’s normative, that’s okay. You don’t need to beat yourself up for being a little bit weirded out by this change, the other kind of reason for optimism is all the science suggests that we have these moments when we’re ready to put in good habits doesn’t happen often, behavior change is usually very hard, but we have these like moments where it’s easier to make a big change, so if you have a big birthday, you turn 30, you turn 40, right, or you move, you start a new job, it’s just easier, or we’re at least more motivated to try out new things, this is some work by Katy Milkman on the Fresh Start effect.

LS: She’s a professor at Wharton. And I think the nice thing about the big back to work is that we all have this moment for a kind of collective Fresh Start effect. As individuals, there’s new habits I want to put in as teams in our workplace, and as managers and leaders, it’s something that you can think about like, Hey, how are you going to make good use of this Fresh Start effect, let’s hope this is our only global pandemic rodeo that we’re going to live through.

BB: Jesus, please.

LS: Let’s hope this is the only, but then that means like, “Hey, this is a big fresh start moment that we’re not going to get again, how can you be intentional about thinking what you want that to do for you personally and what you want that to do for your teams and organizations?”

BB: Yeah, it’s so funny, I was talking… Who was I talking… I think I was talking to Priya Parker about it. She wrote the book The Art of Gathering, and I just love her work and I said, I’m calling it, I like to name things to help normalize, that’s just kind of my jam and my research, so I’m calling it the Big Awkward. And let’s just like, let’s just call it the Big Awkward like even I did an event last night, first in person kind of speaking event since the last one, which was like March 4th, 2020 at NASA. And I got there and I was masked and some people weren’t, and then it was just like people were trying to shake my hand, but I’m doing the fist bump now, and then someone came at me with an elbow up and I thought they were falling, so I grabbed it instead of to put my elbow up, it’s going to be the great awkward, but it’s such an opportunity. Right.

LS: Yeah, and I think about this a lot in a university setting, right, many universities have kind of come back a little bit more, we’re doing live teaching at Yale even though everybody’s masked and stuff, and it was this real moment of like, we took this hiatus, what can we do to come back differently, especially these institutions that are like… Again, I mentioned Yale before, the Yale was built for lots of dead white guys, like what can we do to rethink things, rethink how we set up gatherings, rethink how we set up events in 24 months-ish in college time is enough for everybody to forget all the traditions of the past. Basically, because the institutional memory goes really fast when all students leave after three or four years, and so what can we do to rethink this, and I think thinking intentionally, that also puts you in like optimism excitement head space where it’s like, “Oh my gosh. All these kind of cool things,” it’s like you’re planning a birthday party for everyone like, Oh, what can we build in and do this right, and so I think kind of trying to get to that head space, but giving yourself grace if it doesn’t happen instantly, we’re all going through the big awkward. I think the other strange thing about the big awkward is like you can sometimes feel like it’s just you. It’s just me.

BB: Oh God, that’s it.

LS: I’m the only one that wants to wear slippers and elastic waist bands all the time, you forget that all the other people you see on your Zoom screens are going to feel the same way, because again, we don’t share the stuff when we’re feeling awkward about stuff. And so I think recognizing that you’re not alone and talking about it with your teams where you say, “For real, how are we all feeling really about this, what are the pain points about coming back,” and then thinking about if you can solve some of those pain points creatively, because this is the moment to do a big refresh.

BB: I love this. Okay, first, let me just stop and say thank you. There’s a couple of things you said during this conversation that are very helpful for me, and I maybe intellectually know some of the things you’ve said, but I forget… And this is why I love your work. My brain and my cognition and my thinking is not always on my side.

LS: Yeah, it’s sad, it’s a sad realization, and I think it can kind of be weird, like what does it even mean when you’re…

BB: Yeah, it kind of hurts me.

LS: Like its strange that your mind lies to you, it’s your mind, like who else is up there saying, “Well, that’s wrong,” but I think this is one of the big things that we see when you start taking action to live a flourishing life, to live an authentic life, to lead well is to recognize that you are not your thoughts. There’s a lot of stuff in there that’s floating around from some outdated stuff that happened to you when you were six or some cultural norms that you definitely don’t want to apply to you, there’s stuff you don’t even realize until someone calls it out and you’re like complaining to your husband on a Wednesday about deep norms for dishwashers, you’re like, “Wait, I guess it doesn’t matter,” it takes a lot of work to recognize there’s just stuff jumbling around in there that’s not authentically you, and then you realize, “Well, none of it is.” I can actually challenge a lot of my thoughts, and that is a powerful, powerful step, then you just have to do the harder work to notice and be there with them, like to notice and be with the nasty thoughts and the nasty emotions and the stuff that’s uncomfortable, but if you’re able to do that work, it can give you powerful traction on being like, “Well, I don’t have to listen to my mind, my mind is telling me this stuff, I don’t have to listen to it,” and that’s huge. It’s just super powerful.

BB: Yeah, sometimes I have to tell myself, my mind is trying to keep me safe from something that really doesn’t pose a danger. You know what I mean? I used to kind of talk to myself like, “Shut up, come on, this is not true,” but now I realize that those thoughts, those cognitions, those things, I have to kind of invite them to sit down and say, “look, I appreciate what you’re trying to do here.”

LS: Yeah, and I think this is the grace. I think when you first realize you’re like, “Wait, my mind’s lying to me,” you can get annoyed with your mind like, “shut up my… ” It’s like your angry sibling relationship with it. And this is, I think, part of my training, my early training of thinking about monkeys and thinking about us as primates is you realize it’s not out to hurt you, it’s really trying to help. It’s genuinely trying to do the best job it can. Given that it’s a brain that’s running around in 2021, and it was built for life on a savanna where the main things you had to worry about were tigers jumping out at you. It’s prone to freak out, it’s on a hair trigger for scary things, it’s definitely on a hair trigger for scary social things because being ostracized is probably the worst thing possible, that means…

BB: Death.

LS: Death, right? Death, super bad. And so when you realize it’s just doing its best, and when you understand its design feature is better that it’s elegant, it can kind of induce a little bit of wonder and awe. I was doing a podcast episode with the psychologist, Faith Harper, who has a bunch of books like Unfuck your Emotions and sorry to get. Unfuck Your Anger.

BB: Oh no, you’re good.

LS: We were talking about anger, and she’s like, “Anger, it can get you into trouble, but it’s so beautiful, it’s kind of cool that somebody’s slight movement of a car can induce road rage so fast.” That’s amazing that your emotion, so much processing happens so fast and the emotion is there. And it’s the same thing that was built to protect you and get you to do your fight or flight correctly in the savanna. Yeah it’s going to because you to flip the guy off and maybe do some driving behavior, you’ve got to regulate it and deal with it in the modern environment. But it’s kind of cool that your mind has got this big protective instinct.

LS: And so from that perspective, it allows you to do the thing you were saying that’s so powerful, it was just not to sibling fight with your thoughts and emotions. But thank them to say, “All right, let’s both sit down. First off, thank you. Thank you, anger. I know you’re trying to help me. I know you think that the car is some weird savanna thing and you’ve got to react, but you don’t. I heard you, I heard what you’re saying. Anger. Thank you. I’m going to just go it my own way, I know some stuff you don’t, but… ” It’s this gratitude for the negative emotions and what they’re trying to do, and to be happy that you have these strong, very fast, really intense reactions, because they’re trying to help you and you can learn something from them if you really pay attention. But then at the end of the day, you thank them and then you say, “Okay, bye bye.”

BB: No, it was shame. I have to tell myself all the time, especially if I’m going to do something where I’m putting myself in kind of a social situation where I can be easily criticized, I do this self-talk all the time, I always say, “Look, I understand that you’re trying to keep me from getting criticized and judged. I think I can take it, I think I can handle it. I think this is worth it for me. I appreciate it but… ”

LS: Yeah. This does feel different. I’ve heard this idea of giving your negative thoughts a name, and it can be… Sometimes you use like, “Thanks, Linda lame sauce anger, but let’s not do this.” But then sometimes I genuinely… And I feel like sometimes with shame, sometimes with the deepest darkest ones, I find that I want to do the like, “Thank you, I want to hold you close. Thank you, shame. You really are trying to help me, but I think I got this.” It can be kind of powerful too, because it’s so easy to pretend you’re shooing them away, but you’re just kind of letting them fester, so to really sit with it, you kind of have to have this compassion and wonder and awe towards them. I find that you’re just as a psychologist, as I learn more about how our mind lies and how it works, it’s a system that’s annoying, it doesn’t work all the time, it leads to a lot of unhappiness, but it is built intricately for this purpose, and when you see how it works, you’re like, “Dang, I couldn’t have designed something this good.” You can have this wonderful appreciation for it too.

BB: Yeah, and I think a lot of times those emotions… We’re not on the savanna, but a lot of that kind of… Especially the shame stuff, was really trying to keep me safe when I didn’t have agency of an adult. You know what I mean? I’m a grown woman now and I can do this and I’m making this choice out of free will, but I totally… Yeah, I remember being in the audience one day when this woman was like, “And you look at your shame and you say, go away, you’re not welcome here.” And I thought, “Oh my God, that is… A, that’s not going to work, but B, befriending the dragon is a whole another level of grace.”

LS: Yeah, and sometimes the dragon’s there to teach you something. Sometimes it’s outdated where these thoughts are coming from, their outdate… Shame was left over from before you became an adult who had agency who had certain kinds of resources and so on. But when you see where it’s coming from, you’re like, “Oh, that’s what it’s trying to do, it’s trying to protect old me, and those things are outdated,” but then once you realize that, you can say like, “Oh, maybe I’m not taking the kinds of new risks I could take, what new beliefs do I want to put in there.” When you figure out what belief is driving the bad stuff, you can literally ask yourself the question, what belief do I want? And it’s not easy, but I think it can be quite powerful to ask yourself the question, what are the consequences of believing this thing I believe right now, and what would work differently in my life? How would I feel differently if I just had a different belief? If I wasn’t walking around with that anymore. And it takes some work to get it in there, but it can be a powerful step to just recognize you don’t have to have that belief, you don’t have to.

BB: God, I love this. Okay, thank you for… Yeah, we’re going to need these tools during The Great Awkward, I think for sure.

LS: Definitely.

BB: All right, you ready for some rapid fire?

LS: Yes, let’s do it. Okay.

BB: Fill in the blank for me. Vulnerability is…

LS: Scary but important. [chuckle]

BB: What is something people often get wrong about you?

LS: Oh. That’s so interesting. People often get wrong about me that I’m happy all the time, because I teach a podcast about happiness, but my natural instinct is the opposite of flourishing, I have so many bad intuitions. Yeah.

BB: Okay, what is one piece of leadership advice that you’ve been given that is either so remarkable, you must share it with us, are so shitty, you need to warn us?

LS: I’ll go with remarkable, because I worry that when you share the shitty stuff, it catches. It won’t necessarily have the right source memory tag you’re like, “Was that true that lady yelling said, I don’t remember no.” Good leadership advice that really has changed me is, as a leader, you forget how much of an impact you’re having on the people who you lead emotionally in terms of their thoughts. You have a privilege that’s completely invisible to you, but you’re affecting them all the time. You take the keys of emotions, emotional contagion, if I walk into a meeting feeling like… No matter where it came from, I was annoyed, who put the stuff in the dishwasher the wrong way. I walk into that meeting feeling stressed and curmudgeonly. That’s going to transmit whether I want it to or not, blindly. I’ll be invisible, but I’m going to affect my team negatively. By the same token, I can affectively contagiously affect the people around me in a positive way. And that’s been transformative for me because it reminds me that I do have to put my own oxygen mask on first. Even for someone who teaches a podcast about happiness, you can feel really guilty trying to do nice things for yourself, like prioritizing your own happiness, your own self-care, taking time off, taking rest, you can feel like that’s a bad thing, but realizing if I don’t do that this is going to have a negative consequence that’s going to spiral for my team, huge.

LS: This is what Wharton researcher Sigal Barsdale calls an Affective Spiral, this idea that you seed some emotion and then the rest of your team picks it up and they bring it to their other team members and back to their family, and it can kind of go in these spirals, but recognizing that as a leader and the evidence suggest leaders can seed these things more effectively, just because people look at you more, you just… More attention goes to you, recognizing that you can see positive change if you want to, and you have a duty to do that. It’s been really huge.

BB: Wow. God, painful, but I needed to hear that. Yeah, I’ve literally watched it happen. You can’t always visually see it and rarely, but I’ve visually seen that happen before.

LS: No, me too, me too. And you kind of get it three hours later, Oh, that was the mood I was in at 9:00 AM, that was the slight, snarky tone I used, and it’s transmitted back to me and I’m watching my teammate transmit it to someone else, and you want to be like, “No, no, no, I didn’t mean the snarky tone, it was just the dishwasher.” But now it’s gone. And especially for me with taking rest, I think it’s being in this Yale environment is being in the modern world, toxic productivity, it can be hard when I feel like a team is relying on me to take a break to take rest, to take weekends off or whatever, and recognizing that when I don’t do that, it’s going to be worse for everybody. It can really give me permission to do it in a different way.

BB: It’s powerful. Okay, what is the hard leadership lesson that the universe keeps putting in front of you that you have to keep learning, unlearning re-learning.

LS: Oh man, I feel like there’s so many of them. The universe is laughing right now. It’s like, “Oh, pick one of the 7,000 we’ve been trying to teach her.” Yeah, the one that has been the biggest for me lately is time. Is recognizing that time is a resource that’s precious and that I need to make good on. One of the things we talk about a lot in my class is this idea of time affluence, this objective sense that you have some free time, and there’s lots of evidence that feeling time affluent is great for your flourishing. In fact, the opposite feeling, time famished is awful awful, awful for your well-being. If you self-report being time famished, researcher Ashley Whillans has these data, if you self-report being time famish, that’s as big a hit on your well-being as if you self-report being unemployed or it’s literally like losing your job if you just say, “I don’t have any time.”

LS: But we have some control over that. We’re the ones who structure our calendars, we could choose to take on less and choose to say no more. And there are lots of times when I don’t do that, and then I have a calendar that’s packed and then I feel time famished, and then I feel overwhelmed, and then when I finally do get leisure time, I’m too exhausted to do things that will build me up so I plop, and then I never get refreshed and it was all on me. I know the research, I should have just done it differently. For me, it’s the consistent lesson to protect my time and that sometimes you have got to say no to even really, really good tempting things, just to keep yourself with a little bit of space. I’m sure you can’t relate to that at all, Brené.

BB: Painful, painful.

LS: I’m sure you’re totally… Yeah, don’t know this, yeah.

BB: Yeah, shit. Tell us one thing you’re really excited about right now.

LS: I’m excited about so much stuff right now. What I’m most excited about is that I was just starting a new season of our podcast this coming January on facing down negative emotions in a good way. Letting negative emotions be your teacher, which is one of the reasons you came on to talk about your new book, but we’re going through all the emotions I struggle with the most. Anger, anxiety, overwhelm, and we’re saying how you can look them in the eye and thank them and say, “Thank you for being my teacher, what should I learn from you?” And just hearing all this advice has felt so amazing to me, so I’m excited to share it with all my listeners too.

BB: Oh my God, I cannot wait. What’s one thing you’re deeply grateful for right now?

LS: Oh gosh, I’ve such gratitude for so much you’re going to make me cry. I think right now, you and I are having this conversation right around the time that Yale is going into a big break, and we’ve just had such a busy week getting everything sorted for our students, and I have such amazing staff who’ve helped and they’ve taken on crazy hours been around student… They just been my rock in a way that I just couldn’t do what I do without them there, really just my staff and just their hard work and great intuitions and ability to put up with me, especially when I’m feeling really busy.

BB: God, we had an all-hands this morning, it was our last one before we go out for a week, fall break, and we did a gratitude check in this time to start the meeting, and I just said, “Y’all, yeah, I just… ” Sometimes have to pinch myself, I cannot believe that this is the team that I get to be on. It’s incredible, right? All right, this is my favorite part, okay, and I love your songs. We asked you for five songs that you can’t live without, because we make many mixed tapes for all of our podcast guests on Spotify, here are the five songs that you gave us, “Bitter Sweet Symphony” by the Verve. God bless, that was such a good song, “What a Wonderful World” by Joey Ramon.

LS: Yeah, that definitely his version, because you want to punk rock out to that song.

BB: You want to punk rock out to that song. “Just Like Heaven” by Kat Edmonson, and it’s a cover of the Cure song.

LS: And she just has an ethereal voice that however, I’m feeling, listening to that song makes me feel present and just kind of into life.

BB: “This is How We Do It” by Montel Jordan.

LS: And that’s just… You’ve got to have in your playlist the cheesy pump-up song, you’ve got to have that in there.

BB: Wait, is that “This is How We Do It?”

LS: Yeah, it brings me back to college. It just brings me back to happiness, yeah.

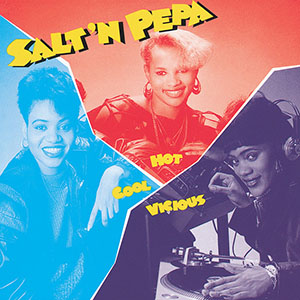

BB: And then number five “Push It” by Salt and Pepper.

LS: By Salt and Pepper, yes. And that’s just… What I went with… You basically give your guests an impossible task, how to pick only five? And I really went with revealed preferences, I went on my Spotify and I was like, “Okay, just tell me Spotify, what are the ones that are always… ” And these popped up and I was like, “Oh, they’re each there for different emotions, but I would never part with any of these.”

BB: Well, I’m going to challenge you one last time before we get out this podcast, you have to give us in one sentence what this play list specifically says about you, Laurie Santos?

LS: I guess is I never… This playlist says that Laurie Santos never left the ’90s, but she still has good music taste anyway.

BB: I love it. You know what, thank you for being with us, and thank you for helping make our lives better. Thank you for challenging us.

LS: Ditto, ditto 100,000%.

[music]

BB: Okay, y’all I love this conversation as we head into The Great Awkward. First of all, as we head into the holidays, that’s constantly The Great Awkward, that’s The Great Awkward and The Great Overwhelm, and then as many of us return to gathering, which is so exciting, I think holds so much possibility for connection and reinvention, but also awkwardness. I think Laurie’s wisdom is just very helpful right now, you can hear her podcast, The Happiness Lab, wherever you like to listen to podcast. We’ll put a link to it on The Dare to Lead episode page. You can find Laurie online at Dr. Laurie Santos, and it’s L-A-U-R-I-E, Santos S-A-N-T-O-S dot com. She also has the website psychologyandthegoodlife.com. And you can find all of our social media links on the episode page. Things not to forget. Oh, holy shit, Atlas comes out tomorrow. Oh, I’m excited, nervous. It’s always weird to put a new work into the world, but I’m ready for it. Our event for Atlas is Thursday, December 2 at 8 PM Eastern Standard Time. Again, partnering with 150 bookstores, independent bookstores across the US and Canada. You can find everything that we’ve talked about, all of Laurie’s information and all of the Atlas launch information on our relearn dot-com episode page.

BB: All right, y’all stay awkward brave and kind and so deeply grateful for you. The Dare to Lead podcast is a Spotify original from Parcast, it’s hosted by me, Brené Brown, produced by Max Cutler, Kristen Acevedo, Carleigh Madden and Tristan McNeil, and by Weird Lucy Productions, sound design by Tristan McNeil. And the music is by The Suffers.

[music]

© 2021 Brené Brown Education and Research Group, LLC. All rights reserved.