Brené Brown: Hi, everyone. I’m Brené Brown, and this is Unlocking Us.

[music]

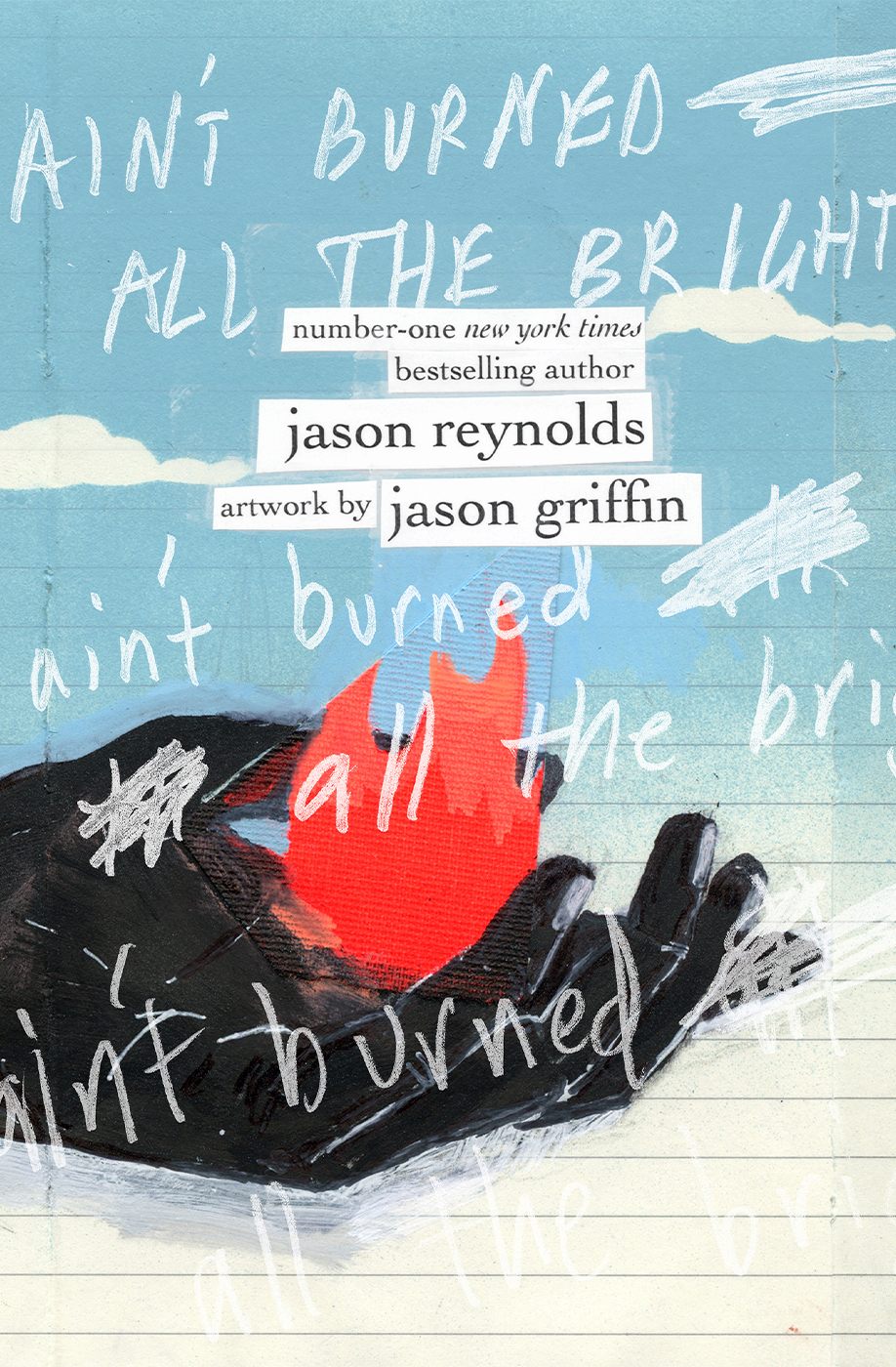

BB: I’m so excited about this conversation today, you’re going to meet Jason Reynolds, he is a number one New York Times best-selling author of more than a dozen books for young people, and we’re talking about his latest book, Ain’t Burned All the Bright, that he wrote with artist Jason Griffin. This book is art. I have ordered this book for so many people, you would not even believe. It is basically three sentences over a couple hundred pages of art, and I haven’t… I’m trying to think of how to describe it for y’all. I wasn’t going to say read or observed or engaged with, I haven’t seen art and words laid out in front of me before that captured so much of what I’ve experienced over the last two years. This was so profoundly moving for me. This conversation was just bomb. Jason is an incredible human being, a poet, a thinker, an artist, a social observer in kind of the most soulful way, so I’m so glad you’re here, and I’m really just grateful to be able to share this conversation with you.

BB: Before we jump in, let me tell you a little bit more about Jason, he is a number one New York Times best-selling author, a Newbery award honoree, a Printz Award honoree and a two-time National Book Award finalist, a Kirkus Prize Award winner, a Carnegie Medal winner, a two-time Walter Dean Myers Award winner, and an NAACP Image Award winner. And he is the recipient of multiple Coretta Scott King honors. He’s also the 2020 through 2022 National Ambassador for Young People’s Literature. His many books include All American Boys, When I Was the Greatest, The Boy in the Black Suit, Stamped, As Brave As You, For Every One, the Track series, which is Ghost, Patina, Sunny and Lu, Look Both Ways, and Long Way Down, which received a Newbery Honor, a Printz Honor and a Coretta Scott King Honor. He lives in Washington, D.C., and you can learn more about him at Jasonwritesbooks.com. Let’s jump in.

[music]

BB: Welcome to Unlocking Us, Jason Reynolds.

Jason Reynolds: I’m so happy to be here. Hi, Brené.

BB Hi. Oh, I just… At some point, maybe in the next 10 minutes, I’m going to stop grinning like this, but I don’t think it’s… [chuckle] I don’t think it’s going to be before then because I feel connected to you cause we’ve kind of done work together before in, You Are Your Best Thing with Tarana, but we’ve never met.

JR: I know, this is a big deal for me, too, by the way, my mom’s excited, everyone’s… Everyone’s very happy [laughter]

BB: Okay, tell your mom I said “Hi.”

JR: I will, I will.

BB: And that we need to talk later. Well, it’s just a pleasure and I’ve got so many questions for you, but before we get started with the big question I like to start with, I just have to say… This is not a book.

JR: Thank you. I appreciate that.

BB: Ain’t Burned All the Bright… Not a book, it’s a… I don’t know, I don’t know what it is, when we talk about it maybe I’ll know it’s a… I don’t know. It’s art, it’s poetry, it’s a challenge, it’s an epitaph.

JR: So far you’re nailing it. [laughter]

BB: It’s just… It’s incredible. Okay, let me start with this question. We want to know your story, so will you tell us your story?

JR: Sure, of course.

BB: Okay, going all the way back to baby Jason.

JR: Okay. I am the only born son of Isabel Reynolds and Alan Reynolds, the only born son of Isabel, but my mother… My father had other children, and I was raised in Oxon Hill, which is… I was raised three blocks from the Washington D.C. line in a house full of people and full of love and full of really strong individuals. My folks come from the South and they experienced all the things that folks from the South experienced, specifically Black folks from the South experience, and so I was raised in a household full of really strong women who did not suffer fools and who believed in hard work, who believed in persistence, who believed in being proud of who we are and where we come from, and what we are, and what we have or what we don’t have for that matter, we always were sort of taught to look at each other as if we were the greatest thing that ever existed, so I was raised in a house like that, my mother… I’m doing this work right now as getting into this…

JR: My mother, when I was a two-year-old, made me say that I could do anything every single night before I went to bed, from two all the way up until to this day, sometimes she ain’t even here, she… At her house, but sometimes I still whisper it to myself, it was like this sort of mantra, sort of drilled into the heads of her children, because she wanted to make sure that we understood that the world was ours, that we could eat the world if we wanted to. That we could be whatever we wanted to be if we wanted to and so to be raised in a house where all you know is that you could do anything you want by the time you’re 10 or 11 years old like me, it was sort of like, “Yeah, I can do”, I don’t feel the limitation. And besides that, I was raised by a woman who was progressive enough back then to understand that it was important to have her children talk back and this is a no-no in most households in Black communities, it’s like a No, no, no, no, no, no, this is a big deal, and… But my mom was sort of like, “If you got something to say, if you disagree with something I’ve said, even in my disciplining of you, if you disagree, you could say so, respectfully, you could say so.”

BB: Wow.

JR: You could say… Yeah, I know it’s an interesting thing. I could look at my mother, she could come home and say, “Jason, I told you to do this, you didn’t do it yadda yadda yadda yadda yadda.” And I could look her in the face and say, “Mom, I just feel like you’re talking to me in a way that’s unnecessary and a little mean.” I can say that. I can say, “Ma, you hurt my feelings, and I’m not sure that I deserve… I know I messed up, but I don’t know if it deserves all of this.” Right? And usually she’d say, “Okay, you’re right, I apologize for speaking to you in this manner, but I don’t apologize for disciplining you, because you’re still wrong, and you still have to know you’re wrong,” and we can have discourse with each other.

BB: Wow.

JR: And the reason she wanted me to do this is because… Her theory was, “I can’t expect my child to go out into the world and express himself, if he can’t express himself here. I can’t expect him to go out into the world and stand on his own word, and stand on his own square, if he can’t do that in his own house with the person that he feels the safest around.” Right? And so that was the way I was raised.

BB: Wow.

JR: I could say anything. It was great, and because of that communication, I also never felt fear to say whatever I needed to say even when it came to the exploration of myself. I could go to my mother. I never had to go to anybody else. I could go to my mother and say, “Mom, I’m having these feelings about sex, I’m having these feelings about drugs, I am having… ” I could say anything, and my mother was like, “Cool, let’s have some discourse.” I also was raised in a household with… My mom was experimental when it came to anything that had to do with her spirituality. And so because of that, I was raised sort of like… You know like everybody… Everybody’s sort of way of doing things…

JR: My mom is very sort of… She’s 76, and she’s like, “Yeah, I see y’all, your generation, all these girls and they got their crystals, and they got their this, that, and everybody meditating and doing Yoga. You know I was doing that in 1960. You know I was doing that.” She’s very might like, “I’ve meditating since I was 17.” And she was one of these women who came up and sort of all of the… What we’re now calling all sorts of names, but for her it’s like, this is a new way. This is ancient, ancient sort of philosophies and schools of thought, and she was sort of brought up in that. And so because of that, I was never raised to believe in shame. I never was raised… Because we’ve never heard the word sin. I never heard it in the house. So I’ve never had to carry the weight of shame and guilt.

JR: Well, guilt sometimes when I did something wrong, but shame, because shame is about the person. Shame is about your… Who you are. That’s tethered to the fibers of your personhood. Guilt is about an activity, something you did. No shame in my household. No shame in my life. I don’t know it. I never… I wasn’t raised in it. Don’t know nothing about it.

BB: Wait. I’ve got to ask you this. I’m like, “Who raised your mom?”

JR: The wild thing about my mother is… It’s such a good question. My mom was raised by a farmer. Two farmers basically. A farmer and a farmer’s wife. For that generation. 1930s and ’40s, South Carolina, rural South Carolina…

BB: Whoa.

JR: Is where she was raised. But when she was a young woman, she was taken to a funeral, and back then in the South, especially where we’re from, they would take the kids to the funeral, this is some old folklore type of stuff. They take the kids to the funerals, and if you had a young child you would pass the baby over the casket, because the theory was, if you pass the baby over the casket the deceased relative would recognize the child and not haunt the child in the after life. Like, “oh, that child is mine.” And so my mom talks about how when she’s passed over the casket, the fear and it traumatized her at a young age.

BB: Yeah.

JR: And it started sort of this quest to try to figure out what exactly death is about. And because she couldn’t figure out, no one could explain it in a way that made sense to her. She started to study all sorts of other things. As like a 17, 18, 19-year-old. Because all it was, “I need to know what happens after this is over.”

BB: Wow.

JR: Right. And so then she meets people… So they moved to DC, she meets people who were like, “Oh well, I have a meditation circle,” or, “Oh, I have a friend who does this,” or, “Oh, I have a friend who believes this,”, “I have a friend who teaches this,” and my mom is sort of open because she’s just on a quest to understand, like, “there has to be more to death than just doneness.”

BB: Wow.

JR: And that’s what sort of sparks this whole other thing.

BB: And it sounds like too, not only does it generate this question for her about death, it sounds like it also put her on alert around the seriousness of trauma.

JR: Absolutely. Which of course, influences the way she raises me. And the way she and the way she raises us. It’s like… And my mom will tell you, my mom… We talk about this all the time. My mother was not raised in a… I won’t say it wasn’t a loving household, but it wasn’t loving in the way that we view loving. It wasn’t a sensitive household. It wasn’t a…

BB: Was it emotionally stoic?

JR: It was stoic. Well, it wasn’t emotionally stoic because they were very emotional, just not in an affectionate way. [laughter]

BB: That means something. Hold on. So they were very emotional, but not in… Ah, got it. Okay.

JR: Not in…

BB: That makes sense. Yeah.

JR: Not in an affectionate…

BB: I got some folks in the line.

JR: And so because of that, my mother didn’t necessarily know how to be affectionate, soft, touching, and she always says, “You know, when you were born I had to learn how to give a hug, because I didn’t want my child to not know the warmth of that,” “I didn’t want my child… ” And my mother always talking about how her mother never told her that she loved her, and when my mother asked her on her death bed, “Why didn’t you ever tell me you love me?” She told her, “Because your oldest sister needed it and your younger sister needed it, and I knew that you would be the one who could manage without it,” and my mother said, “But I needed it too.”

BB: Yeah. No.

JR: And so when I came around, it was kind of like, “I’m going to give this boy everything I got, and everything I didn’t have to make sure that he grows up as a whole person,” and we got into a lot of things really young because I was curious about a lot of things really young. When you raise a kid like… I mean, we all know the the precocious kid. When you raise a kid like this…

BB: Yeah.

JR: Then questions are going to come, and when you raise an open child, then that open child is going to befriend people who maybe other people wouldn’t befriend, especially back then. So I remember when my first friend comes out to me. I’m in the seventh grade. My buddy Anton comes out to me and he’s one of my closest friends at this time, and I go home, but I’m in a Catholic school at this particular point in my life. My parents split, my mom was like, “I’m taking you out of public school.”

BB: Yeah.

JR: We going to figure this out.

BB: Yeah.

JR: And then I come home and I’m like, “Yo, so Anton’s gay. Which is fine with me, but does that mean he’s going to hell?” And my mom is like, “Why would you think that?” And I’m like, “Because people say the Bible says that that means he’s going to hell.” And my mother in complete confidence looks her child in the face and says, “Baby, if that’s what the Bible says, then the Bible is wrong.” Now, this is something… [laughter] Because for her, it’s like, “I don’t care. There’s nothing on earth that’s going to have my child believing that the people he loves are doomed.”

BB: That there’s something wrong with him. Yeah.

JR: I don’t care what rule I’ve got to break. I don’t care who I’ve got to disrespect, I don’t care how controversial it is, my baby will not grow up to be hateful, or to be fearful of other human beings who don’t deserve hate or to be feared.

BB: I have to take a pause here and point out something that I just had to… I have goosebumps because I have a total parenting learning moment from your mom, which is when my kids have come home from school and said, “Hey, I’ve got a friend who’s come out as bi or I’ve got a friend that’s come out, and are they going to hell?” I just jump in and say, “Of course not. That’s ridiculous”. But your mom says, “Tell me why you think that?”

JR: Yeah, tell me why.

BB: And then… Because then you get to say, “Because that’s what I’m hearing,” and she gets to really address it.

JR: And she was clear to say “if”, if that’s what the Bible says…

BB: Oh…

JR: That was a big deal. If that’s what the Bible says, then it’s wrong. Very plain and simple. If that’s what it says, oh, that’s wrong. There are other things I think is right, there are things I think are right, and there are things I think are wrong, that’s wrong.

BB: Your mom is a complete badass.

JR: Yeah.

BB: I mean, God.

JR: All the way, all the way. She’s the best.

BB: Let me ask you this question. Okay, so we’re in middle school now, you’re in Catholic school, your mom is just incredible, and I’m also… I have to tell you that I’m struck at this moment, talking about aesthetic force. I’m struck in this moment that we’re talking about, the kind of lack of affection that your mom came from, and I’m talking to you right now and looking at these incredible photographs of nothing but affection behind it.

JR: Absolutely.

BB: Talking about the ability to change something that embedded in a single generation, if you’ve got someone as transformative as your mom. Like, wow!

JR: It’s a big deal.

BB: Oh my God, it’s a big deal. So let me ask you, we’re in middle school, you’re in Catholic school, you got your mom, how is this openness and fearlessness and vulnerability and insatiable curiosity playing out at school and with other people? How does that work?

JR: One important thing that I skipped about this journey is that I literally skipped a grade when I was in the second grade. So by the time I get to middle school, I’m only 10 years old. Well, Eastern middle school was seventh and eighth. Seventh and eighth.

BB: Oh my God, you’re ten… Wait, you’re 10 in seventh grade?

JR: In the seventh grade. In the seventh grade and I’m small, very small because I’m two years behind everybody and sensitive and open and curious, and so the usual things happen, you go through a little bit of bullying. It was enough bullying to let me know that I had to learn that everybody wasn’t going to be okay with who I was and the way that I spoke and the things that I believed. And so unfortunately, you learn to kind of maneuver that a little bit. Okay, well, maybe next year, I won’t tell everybody I’m 10 years old, because I came in and I felt so like, “tell us something interesting about yourself first day at school. Introduce… Say your name and tell us something interesting about yourself.”

JR: “My name is Jason Reynolds. I’m 10 years old.” And they’re like… Because I’m just naive, and they’re like, “Oh, we’re getting ready to give it to him, he going to get it.” And this is my first time in private school and Catholic school, we got a uniform… My uniform is getting smaller and smaller by the day, because my mother doesn’t have but a few different pairs of pants that we got to cycle out and wash. And then they’re going from blue to gray. I’m dealing with all of that. I’ve never had a haircut, because my father used to cut my hair. My parents aren’t together anymore, and now we’re having our differences and now my hair is all over the place, and in my community, you got to keep your hair cut. It’s a big deal. It’s like a cultural force field, you know what I mean?

BB: Yeah.

JR: And so all of this is happening and it’s rough. The hardest year of my life was… One of… The first one was seventh grade. Terrible. I’m failing school. All the things are happening, I’m angry at my parents. I’m angry at the fact I go to this… At the time what I thought was a stupid school. I’m like, “why am I here?” I miss my friends, I miss the neighborhood, I miss my own clothes, and so it was showing itself, and it was the first time that I had suffered a consequence for being who I was, and that was hard. That was hard, and there was a moment where I tried to conform, because I just didn’t want to feel that way, and so I come home and I say, “Ma, you got to start buying me name brand clothes, I’ve got to get fly… I’ve got to… ”

BB: Yeah.

JR: I’ve got to get dressed at least so that whenever we have a moment for a school dance or a game or something, I could put on Tommy Hilfiger and Polo and I can get Timberland boots, but my mom couldn’t afford it. Then what happens is, because she’s such a good mom, she’s like, “I’ve got to figure this out for my kid because I don’t want my kid being teased.” Yeah, she could have said, “You are who you are, and it’s okay.” But she’s like, “You know what? I don’t want my son… I don’t want any of my children being teased,” and so because she can’t afford the name brand clothes, she waits for the off-seasons, and then she goes and she gets this stuff for like 70%-80% off. And so now it’s like summertime, but I’ve got a winter coat on because I’m just so happy to have one of the name brands…

BB: Yeah, yeah, yeah.

JR: And I’m like, “Do you see that horse… ”

BB: Oh, my God, yeah.

JR: I’m like, “You see that Polo horse right there?” They’re like, “Bro, you got on a flannel, it’s August.”

[laughter]

BB: Oh, my God. It’s bringing back such… Like my palms are sweating. Look at my palms because we were the same way. My parents just said, “No, you’ll have to get a job babysitting,” but the only stuff I could afford that had it was from a store called Solo Serve and it didn’t have off-season, but it had clothes with slight mistakes.

JR: Oh, yeah.

BB: So like the horsemen on the polo shirt’s head was missing or it was askew a little bit, and I just would collect as much of it as I can, and every time I wore it they’d be like, “Dude, the alligator’s facing the wrong way.”

[laughter]

JR: You’re going the wrong way.

BB: And I’m just like, shit there’s no winning here.

JR: And that’s what it was, that’s what it was. And it didn’t last very long, because I realized that it just wasn’t worth it, because she let me, she’s like, “My kid knows himself, he’ll come back to himself.” and so, I did it for a year and by eighth grade I was over it. And I was like, “You know what? I don’t want to, I don’t want to wear this. It ain’t me. It ain’t for me.”

BB: I’m stepping out of the race to nowhere.

JR: I can’t do it, and honestly, by then I was cool in middle school again. I had figured out how to make my own bones, and it was sort of like, “I don’t got to do this. I am who I am, and yeah, I’m only 11 years old, but now everybody’s my friend, and whoever is not my friend is not my friend, and it’s all good.” And that was sort of what it was. And I actually adjusted in that way, but then high school came and now you’re 12 in high school.

BB: God dang.

JR: So it starts all over.

BB: This is like a serious… Yeah.

JR: [chuckle] It starts all over, but high school, that first year, it was sort of like a strange time, because you do things that you believe that a 14, 15, 16-year-old would do, because now I know better than to tell anybody I’m 12.

BB: That is not your… Here’s something interesting about me statement on the first day of high school.

[laughter]

JR: No, I learned my lesson, right? I only got to get hit one time, I’m good. And so instead of telling people I’m 12, I just start acting what I think 14, 15, 16 acts like.

BB: Uh oh…

JR: Right?

BB: That’s dangerous, though, right?

JR: Of course, of course, and so you find yourself in precarious situations.

[laughter]

BB: And precarious is code for… I’ve been in precarious situations, but… So you’re experimenting. You’re…

JR: Of course, I mean look. I’m 12.

BB: Yeah.

JR: And I could date 16-year-olds.

BB: Oh God… [laughter]

JR: Right? They don’t know I’m 12, but I’m in the school with them. Right? That’s what’s happening…

BB: Have you grown at this point?

JR: No.

BB: Are you bigger?

JR: I got two more years before that happens.

[laughter]

JR: So I’m a little… I’m small, I’m moving through it, you know what I mean? I’m doing the best I can, and honestly… Young men, young people, but young men, I find, we find ourselves in situations where we posture. Right?

BB: Oh, yeah.

JR: We’re trying to figure out, one, where the line is, and also how to draw the line around ourselves. How do we create the force field?

BB: Mm-hm.

JR: Right? How can I feel safe in this space that is this school, and how can I feel safe within my body simultaneously? And so, we try to figure out ways to do that, whether it’s the way we dress, the way we talk, the way we treat the opposite sex, right? All of that stuff is happening to me as I try to move through the school and figure out what it means to be a high school student. And what it means to be 12 in a building where there are 18-year olds. That’s a big gap. Right?

BB: It is, I mean, all I can think of right now is picturing my son on swim team, and for some reason they had a swim meet that was like… I don’t know, 10-year-olds to 18-year-olds, and I remember looking at my son on the block as a 10-year-old, and he’s tiny and he’s thin, and he’s little, he’s not gone through puberty yet, and the kid standing next to him has a mustache.

JR: It’s so weird.

BB: It’s like it could be his father looking… Just when you look at it. It’s like, it can’t be chronologically, but you’re like, that’s a grown-ass man.

JR: Absolutely. All the way. All the way, and that’s what it was for me, and that was frightening and scary. And it wasn’t until the summer of my sophomore year. So I went through freshman year, sophomore year pretty much a ghost. And then the summer of my sophomore year, I came back to school and I was six inches taller and 40 pounds heavier.

BB: Okay.

JR: Yeah.

BB: That is so weird that guys do that.

JR: It’s so strange. I mean, it was the wildest summer ever. I came back to school, I changed. I wrestled, all these men, I was a wrestler. My sophomore year, I wrestled 145. I came back to school and I wrestled, we’re literally talking about the course of three months, I came back to school and I wrestled 175.

[laughter]

BB: Okay, so let me ask you this. So obviously, you’re in massive puberty if this is happening.

JR: Of course.

BB: Do you think about high school and middle school, Jason, when you’re writing your books?

JR: All the time. That’s all I think about. Everything that I pull from… I tell people all the time, “listen, the reason I write about the ages of 12 and 16 is because that’s where I’m stuck.” Or really 10 and 16, because those are the two ages that were most pivotal in my life… 10 is when my parents fell apart, 10 is when I started the new school, 10 is the first time I was ever bullied, 10 is the first time I ever started to fail, 10 is when my grandmother died, 10 is when I started to write, 10… Everything happened in the seventh grade. My whole life changed in the seventh grade.

BB: Oh my God, I keep thinking about Portico.

JR: Exactly. Everything happening.

BB: From Stunt boy, like…

JR: Same thing.

BB: He’s up against so much and he’s riddled with anxiety, and…

JR: I mean, that’s who I was, though. I was that kid who just was like… And it wasn’t cool to have anxiety, it was… So you also are trying to mask it, which makes it worse.

BB: Oh, you’re armoring up, yeah.

JR: Of course. You got to. At least you… I felt like I had to back then. And then at 16, it happens all over again. At 16, it’s a different set of things, right? Because now it’s like I’m graduating from high school, and I started college, my mother is sick with cancer, right? My father gets remarried, which becomes a beautiful thing down the line, but it starts off as a really hard thing to wrestle with.

BB: Yeah.

JR: I have a baby brother shortly after… 16 was the same thing, thrust into this new world, this new life. And my writing would then take off again, it would change dramatically, and that would set forth what will eventually become where I am today, right? That 16th year of my life. And those two years are where I kind of hang out at, because that’s what is imprinted on my psyche more than any other year in my life. It’s interesting.

BB: No, it’s really interesting, because I think I’ve read all of your stuff, and you don’t write with those ages in mind. You write with those ages in heart.

JR: Right. Although…

BB: And, I feel emotional, because the hardest things in my life in my 50s are still healing and befriending my sweaty-palmed, nervous, no friends, no place to sit at lunch, 10-year-old and 16-year-old.

JR: Yeah, that’s the weird thing. You know what I ask everybody, I do all these book talks and stuff with my friends and everybody, and the one question that I ask every single person, no matter who they are, is, “if you could go back, if you could look back at your 10-year-old self, not what would you say, what advice would you give, what would you thank your 10-year-old self for?” Because when I really think of… Because Brené honestly.

BB: Oh shit!

JR: Because Brené when I really think about it, and this is something that my dear friend Rachel asked me years ago, and it just shook me to the core, when I really think about it, 10-year-old Jason got it right. My nervousness and anxiety was warranted, I was tapping into a part of my humanity that would carry me on through the rest of my life, something that helped me understand what it meant to care for people around me, what it meant to feel for human beings that I know and do not know, my anger and confusion around my parents’ divorce was warranted.

JR: It was warranted, and I also understand how one could be in a healthy relationship and in a healthy separation, and how we can learn to communicate a little better to the young ones around us to help them know that a transition does not have to mean a failure. It doesn’t have to be a failure. And I learned that, I learned that at that age. Ten was when I decided that I tried to conform and realized that that wasn’t for me, never again would I try. [chuckle] Right, 10 years old was when it was. 10 years was when I learned the empathy of what it felt like to be teased and bullied, so that I could never do it, got it out the way. I can never be that. I can never do that. 10 is when I kissed failure and inadequacy, because finally my grades dropped and I was a kid that skipped a grade. I was a kid who understood, school was a piece of cake until seventh grade, and I had to deal with the fact that now I had Ds.

JR: And I had to convince myself, thankfully, my mother, is my mother and my father, God bless the dead, was my father, he was a wonderful father, and they were the ones who were like, “You know son, your grades only assessed how well you know a particular thing in this class, they do not assess how good you are as a person. Don’t attach the D to who you are.” I learned all that at 10, so I look back and I say, “Man, 10-year-old Jason, every day I wake up and I chase 10-year-old Jason down. If I could tight the 10-year-old Jason, and then I can continue one, to live my life as a decent person and two, create something that feels special and that feels honest and hopefully true for some other 10-year-old out there.

BB: It’s so important. Just so beautiful what you said. Would it be fair to say that 10-year-old Jason was anxious and hurting because he was paying attention and he cared?

JR: Absolutely, all day. And my mother says to me all the time, “Jason, you’re the most feminine person in our family and the only boy.” And when she says feminine, what she is referring to at 76, we know that these terms, there’s also the things that are… But at 76, what she’s saying is, sensitivity, compassion, right. And that’s because as a young person, I was the one who… My mother sort of was like everything that happened in our family before this moment, I’m not going to allow for that or that’s not coming, that’s not going to land on you.

JR: Now, you will have your own struggles, there will be some other things, but you’ll be able to sort of navigate them with a pure heart, navigate them with a little less callous, it’s going to hurt a little more, you’re going to feel it a little differently, but the truth of the matter is is that it won’t destroy you, it will fortify you, it will fortify you, to be able to live with that and to deal with it and to feel your feelings will fortify you.

JR: It does nothing for you to run, it does not help you to pretend like you’re too tough, it makes you a giant to know that your feelings are valid and that it’s okay for you to cry, it’s okay for you to be afraid, it’s okay for you to be a little insecure. It’s okay for you to be anxious, all of that this is a part of your humanity and no big deal, and if you can accept it and live with it and learn how to wield it, it’ll make you a giant. Not a giant to yourself, right? Not a giant yourself, as the saying says a giant looks in the mirror and sees nothing, right? A giant to people around you because they’ll be able to look at you and say, “Man, if he can do it, right? If he can do it, so can I.”

BB: Everything… I hope this comes out the right way, but now that I’m learning more about your mom…

JR: Oh, yeah, she’s the best, yeah. [chuckle]

BB: I see so much of her in your work.

JR: Oh, yeah, yeah, yeah. I’ll tell you what else she gave me. I keep saying that at one of these days that she really is… Whenever we had that talk back stuff going on, or if you want to say something, you could say it. She wouldn’t allow me to mumble it. She wouldn’t allow me to articulate in a way that lacked confidence. So if I was going to say something, if I was going to rebut, I had to sort of roll my shoulders back and pick my chin up, and I had to say it loud enough for her to hear it across the room. You’re going to say something to me, even if it is to disagree, stand on your square, say it like you mean it. And the reason why we went through almost like a training session in our house with this, and the reason why is because my mother, who worked in a corporate world, or worked in insurance, she said, you know, everybody’s fear is public speaking. Everybody’s fear is expressing themselves publicly because everybody’s true greatest fear is being misunderstood, right.

BB: Yeah.

JR: And so, if you can do it, if I can give my kid this muscle, it’ll give him a little extra, it’ll give him a little extra. No matter how talented he is, no matter what he does, if he has the ability to express himself, it’ll give him just a little extra and get him in those extra doors where the jam might be a little tighter, and I’m forever grateful for that as well. This is not my natural disposition, I’m naturally an introvert, but I was raised and trained to be able to move through the world in a certain way because my mom came up at a time where opportunities weren’t cut, opportunities were cut rather if you didn’t have certain skill sets, it’s unfortunate, but it is what it is.

BB: It is the world.

JR: It’s the world and I’m grateful for all of these things that the old lady gave me, she’s the best human I know, I’m telling you. And everybody who knows her would tell you the same thing. [chuckle]

BB: Tell me about high school and beyond.

JR: So high school, after I got big, you know high school was cool. High school, after I grew…

[laughter]

BB: And in the end Jason Reynolds is still a guy.

JR: Absolutely, listen I tell people all the time I’m as human as they come, all the way human. I came back junior year as a different person. You know what I mean? [laughter] And so high school got really fun and interesting. I was not that great of a high school student. I did okay, I did okay, I could have done better, but I was like every other kid, just knucklehead and hiding out in the guidance counselor’s office and all the thing… I was an athlete, all the things… You know what I mean? But I had a few teachers that saw me, two in particular, and the guidance counselor who I loved. I had a teacher named Ms. Blaufaz, and Ms. Blaufaz was my English teacher in the 10th grade, couldn’t stand her, I thought she was the meanest person in the world. I could not stand this woman, I’m saying I could not… I just thought… I went home and you know what it’s like if you got kids, I went home and first day of school, “Hey, ma, you’ve got to get me out of this class. You’ve got to get me out. And she’s like, “It’s the first day.”

BB: We’ve had some of those.

JR: Yeah, exactly.

BB: Yeah.

JR: My Mom was like, “Jason, it’s the first day of school, I’m not… ” “Ma, you have got to get me out, this lady is so mean, she don’t let us do nothing.” My mom was like, “It’s the first day, what did y’all… ” And then by the end of the week, “Ma, you have to get me out because we got a limited amount of time to transfer classes, I can’t stay here because I think she hates me, I think… ” All the things that kids go through, and my mom is like, “Eh, let’s just see, right” And it turns out this is the lady that acknowledges that I can write, first time ever, this is the lady who says, “Hey, man, something happening in your work.” And I wasn’t doing that great on the papers, but she was able to look at the papers, even though I may have been getting a C, she was able to say, “I’m giving you a C, but not because it’s poorly written, really because you’re not following directions, right?

BB: Yeah.

JR: “But not because you’re not exhibiting some sort of chops here, something’s happening in your work, and I can see it.” And then she start to create a writing class, and she hand picks like eight of us to be in this class, and now I’m being introduced to sestinas and cinquains and sonnets, and I’m going through the whole thing, form and everything, I’m like, “Oh, this is it. I love this.” And then she called my mom and said, “If he goes to college, find a college with a good writing program.” This is a teacher that was so invested in a thing that most people could not see in me, and she saw it, and she’s still a very good friend.

BB: I just want to take a pause for all the teachers that say, “Look, I’m giving you a C, I told you this is how you had to cite stuff, it was supposed to be this long, but underneath a C, there’s something emerging here that’s important.”

JR: There’s something here.

BB: That is someone who cares.

JR: Absolutely, there’s something here. I can be critical and constructive, right?

BB: Yes.

JR: I can hold you accountable and still elevate you, push you, both of those things can happen.

BB: Yes.

JR: We’re still friends, she lives down the street from me.

BB: No way.

JR: Yeah, in the Spider-Man book and in the Miles Morales book she is the English teacher, the name and everything is in there. She is the English teacher, Miss Blaufaz, she’s in there. Because I try to honor my… I love her and I’m grateful. And then the second teacher was my senior year, and he’s also one of my close friends, somebody I love dearly, Mr. Williams, and Mr. Williams was completely different than any teacher, I’d ever had. He looked different, he was sort of… He is a skinny white man, he had a bowl cut and he had… And it was stark white, and he wore… And he would put on khakis, but he’d have on, like a pair of Jordans or high-top Nikes, he had his shirt tucked in. He wore fabric… He wore these weird wool ties with the blunt bottom, so it doesn’t come at an angle.

BB: Oh, yeah, the bottoms like this, yeah.

JR: Yeah, and he just looked different than everybody, he had earrings, he was just a fascinating person, and he had traveled the world, he had been to a 100 countries or something on a teacher salary. This was just an incredible man, and he taught a class called Global Studies, which is a class he made up, but you had to pass his class to graduate. Which is fascinating. And so we all go to his class, he’s mean to everybody, all three years, he only taught seniors, and so he would see you in the hallway, if you were an underclassmen, let’s say you had to put books on the floor to put something in your locker, he would come and kick the books, and kick the book down the hallway. [laughter]

JR: He was like a bully, he would kick your book down the hallway, and when you went and got the book, the bell would ring and then you’d be late, and then he would write you a detention. He would write you a detention and not take it back and he’s like, “No, no, you guys go to detention, it is what it is, you were late to class.” “But you kicked my book.” “Well, if you were a little earlier, it wouldn’t have mattered if I kicked your book, it ain’t my fault that you weren’t on time, to be on time is to be early, and what you want me to do? You’re going to detention.” This is who he was, and everybody hated him for this, and he was doing this…

BB: Wait, how old was he when you were in high school. I want to get a mental picture of him, I’ve got the haircut and the tie…

JR: He had to be in his 50s.

BB: Is this guy 60?

JR: Nah.

BB: He’s 50, so he’s not a young guy.

JR: I have been out of high school 20 years. I think he’s probably 70, early 70s now. So he was in his 50s.

BB: So he was in his 50s. He wasn’t a young guy.

JR: No, no, not at all.

BB: Okay, so everybody hates him.

JR: Everybody hates him, and he’s doing this intentionally, [chuckle] because when you finally become a senior, and you’re loathing having to take his class, because you know he’s a jerk, and then you take the class, and you realize he’s the greatest teacher you’re ever going to have, and he completely, sort of like bucks what you think of him. First thing you learn in his class is ethnocentrism, I’ll never forget it. That’s the first thing you learn. The definition, what does it mean to be ethnocentric? That’s where we started.

BB: From this white guy.

JR: From this white guy, because he’s trying to get you to understand that your way is only yours, but the rest of the world has there’s, and everybody is sort of centered in their own sort of experiences, but it doesn’t mean that your sort of life is the only life. There are people who eat crickets as a delicacy, there are people who don’t eat beef, there are people… All of this stuff, we’re going through this whole thing. And so there’s one point in the class, the most important class, we come to class one day, and he says, “Look, I brought in this fish, it’s a tropical fish.” A beautiful tropical fish. He’s like, “I paid a lot of money for this. I got it at this aquarium, this is going to be a class pet.” We’re seniors, so we’re totally, “We don’t need class pets, bro, we’re seniors.” [laughter] But okay, Okay.

JR: So, he’s like, “all right this is the class pet, you guys have to name the pet and I need you to feed the pet when you come to class, whatever you do, just don’t touch the pet. If you touch the fish for any reason, if you touch this fish, I know how you all are with your hands, you playing around trying to be funny, you touch the fish, I’m going to suspend you, no questions asked.” And everyone’s like, “okay, no big deal.” Weeks go by, we come to class every day, we feed the fish, everyone’s looking at it, and now we’re attached to the fish, we love the fish, and then he comes to class one day and he takes a little net, and he digs the fish out and he sits it on the floor. The fish starts flapping around. We’re all mortified, we stand-up, “what are you doing? What are you doing? What are you doing?” We’re mortified, true story, and two young ladies run over, they scoop the fish up, it’s flapping and they throw the fish back in the tank and the fish survives, and we’re like, “wooh.” And he says, “young ladies get your bags and go down to the principal’s office, you’re suspended, the rules are the rules.” And they’re like, “what do you mean, What do you mean?”

BB: Okay, shit man, I’m trying to get the point where this is a good guy, okay.

JR: Yeah it’s coming. And he’s like, “the rules are the rules,” and they’re like, “What are you talking about? What are you talking out? What are you talking about?” And he’s like, “the rules are the rules, I said, don’t put your fingers on the fish, don’t touch the fish by any means, you cannot touch this fish and you touched the fish, so you are suspended. I’ll see you all on Monday, don’t bother yelling or screaming, just get out of my class.” They leave the class and he pokes his head out the door and he says, “But hold your heads up, because you did the right thing, but sometimes doing the right thing has consequences,” and the rest of us had to sit in that class and deal with the fact that we were cowards.

BB: Oh God.

JR: I learned some valuable things that day, number one, here’s what I learned, number one, every day I wake up, I decide to lay it on the line. For me, it comes down to these children, that’s what I’ve chosen to lay it on the line for, all right. There are things that I have done, and will continue to do that put me at risk every day for our babies, and I will continue to do so. And number two, it’s always women who save the fish, always. When you look at history of every social movement, every major change, every revolution, every uprising, at the helm are women. The Civil Rights Movement, they don’t get talked about, they’re unsung for the dirty work, the sacrifice, the people who really, really, really lay it on the line. Nine times out of 10, are young women. And I got to see with my own eyes that day, and I think about it every day, and I have thought about it every single day for 21 years and will probably think about it everyday of my life.

JR: And I see him all the time, I talk to him, he writes me letters every month, we’re very good friends, and everytime I see him, it’s hard for me not to bring it up. I saw him three or four months ago, I was at his beach house, we were sitting at the back of the house on the water, and he said, “Jason, I never told you about… ” How recently he saw a woman that he used to teach, and it had been 30 years or something. And she came up to him and she opened up her purse and she pulled out the note, the suspension note, and said, “I was one who saved the fish.” Always a woman. It’s fascinating, something interesting to think about. I loved him to death, he taught me how to be human in a different way. My mother gave me all the game, but he forced us to be in practice. Let’s see, here we are. He’s retired now, he stopped doing it, I think five or six years ago, because honestly, times change, we learn new things. And there was a young woman who said, “this is animal cruelty,” and he said, “I agree,” and he cut it out, so he just stopped doing it. But it was a life-changing experience.

BB: I swear to God, Jason, I will never forget this story.

[laughter]

JR: Good, me neither.

[laughter]

BB: If you and I ever find ourselves in a situation where we have to save a fish, but we know we’re going to get suspended, I think we do it.

JR: Save the fish. You know how many people come up to me… There are people who have heard that story or who have heard me give it at certain different places, and people will come up to me years later and say, “hey man, I saved the fish.” And they don’t mean it in terms of the literal way, they mean it in like…

BB: Oh yeah.

JR: Teachers who are like, “yo, I’m a fish saver, I’m a fish saver.” It’s a whole thing.

BB: Yeah.

JR: And I’m grateful to… Mr. Williams has been a giant, so he saved a lot of our lives, and I want him to be lifted up, I think he is a phenomenal human, he hates attention, and he just can’t deal with it, he’s a shy person. But when we talk about educators, I’ve never known anyone that took it as seriously as he did.

BB: Yeah, it’s so incredible because one of the things that is a thread through this podcast, and I’ve never felt it as heavy as… I did feel like this heavy of a thread of this when I was talking to President Obama. But the thread here, again is always paradox, like your mom saying, “you can disagree with me, you can share an opinion that’s counter to what I’m saying, you can challenge my decision, but you’re going to do it respectfully and you’re going to stand in your space and do it.” You’re talking about a teacher that said, with the fish story, “you’re suspended, but you did the right thing,” and you’re talking about another teacher who said, “you got a C because you didn’t follow directions, but there’s some talent deep in here that we need to cultivate.” I keep thinking about Carl Jung, who said that the paradox is the only thing that comes close to describing the fullness of the human experience, and I see it in your work.

JR: Oh absolutely, absolutely. Isn’t that what life is? Isn’t that what it’s all about? Somebody asked me recently when it was all over for me, and my time was up on this plane, would I want them to tell the whole truth, or would I want them to print the legend? And I’ll always say, “no, tell it all, let the people know that I was both masterpiece and mess.”

BB: Yes.

JR: Both, both.

BB: Yes.

JR: That is…

BB: That’s integration. That’s human.

JR: Yeah, both. And that there’s beauty, and that all the things exist in both of those things. It’s all there, and I’m okay with that, I’m totally good with it. Look, it’s all there, I promise you, all the humanity is there.

[laughter]

BB: Oh yeah. Yeah.

[laughter]

BB: But that’s the beauty too, it’s like the anxiety, I can really struggle with anxiety. The anxiety, the coming out of your skin, the overwhelm. But then it’s just the same part of me that drives my compassion, and my empathy, and my willingness to get expelled for the fish. They’re inextricably connected. You can’t have one without the other, Can you?

JR: Absolutely. I tell people all the time one of the most beautiful paradoxes to me is writing. And the reason why is because in order to do it one has to live in an extraordinary place of humility, in the process of making something that perhaps might be shared with the world. On the flip side, the mere notion that someone wants to make something that might be shared with the world is rooted in ego.

[laughter]

BB: That’s true.

JR: Yeah, it’s the perfect paradox.

[laughter]

BB: Okay, wait, let me think, wait. I’m like, “Oh, holy shit, that hurts.” But let me think about it for a second. Yeah.

JR: Yeah, it is.

[laughter]

BB: It is.

JR: And that doesn’t make it good or bad. It just is what it is.

BB: It is what it is.

[music]

BB: Okay, wait, I have to ask you, do you believe in therapy?

JR: Of course.

BB: You seem like someone to me that’s done some work.

JR: Yeah, I’m in therapy. Every Monday I’m in therapy, and I love therapy. My father was a psychiatrist. So like that’s the other part of that story is that we also, in the midst of all of that, my father was the director of a mental health clinic. And so, I grew up… He would break all sorts of rules and laws because he also, before that was knucklehead, motorcycles and he was sort of the hustler type.

BB: Yeah.

JR: Got his life together, and becomes this wonderful director of this mental health clinic. And so I remember being a kid and he would bring his clients to our house for cookouts, which is a no-no. But he wanted his kids to be comfortable, all right, around anyone with a mental difference, anyone who was neuro atypical, anyone who had addiction issues or whatever was going on. And so we’d be there and there’d be so and so who may be living with schizophrenia, and there maybe so and so who may have just gotten out of prison. And they were just hanging out at the family house with all the family, and eating and drinking and having a good time. [chuckle]

BB: They’re at the cookout?

JR: Yeah, because he wanted us to be like, “These people are just that. People.”

BB: People.

JR: They’re just people, and it’s all good. And their brains and chemicals in their brains might work a little differently than yours, but it doesn’t make them any less people, and it doesn’t make them weak or small, or weird or any of those things. And so we were acclimated very, very young when it comes to mental health. And so when I started to deal with my own mental illness, it wasn’t that hard for me, after I got over the shock of dealing with the fact that like, “Oh, this anxiety is different than just being a little nervous”, all right. This is a different thing happening to me and it’s happening to my whole body,” And I can’t seem to get a grasp on it.

JR: It was my father who said like, “Listen, I think there are some other things happening here and we need to figure this out.” My father was the one who sort of helped me navigate it, and I’m forever grateful for the old man for that you know. So, yeah. Therapy is great. I’m all the time with it, I’ve been in… Yes. Therapy, therapy, therapy, therapy.

BB: I will counter that with therapy, therapy, therapy.

JR: And you know the thing about therapy is that I tell people, because I have friends who are like, “I just don’t know, I don’t get it”. And I’m like, “I understand, I understand that too”. But I believe and my mother always says this, and she and I joke, “I believe that we have our public lives, we have our personal lives, and then we have our secret lives”. And all of us, all of us had it.

BB: Amen.

JR: And what the therapist is good for, is for you to talk about your secret life.

[laughter]

BB: I mean, that’s… [laughter] I feel so uncomfortable seen right now. [laughter] It’s one thing to tell me about the ego and the humility about writing, but shit man, like this is…

[laughter]

JR: Yeah.

BB: It is. I do. I have a full…

JR: All of us.

BB: Secret life.

JR: Me too.

BB: Where I’m saying shit to people that I would have no career and no life if I…

JR: Exactly.

BB: Yeah.

JR: Absolutely. If people only knew. Your secret life is the ultimate group text. This is the… [laughter] this is like the… [laughter] This is the ultimate group text where if anybody were to read it, it’s over, everything is over. [laughter] So I go to my therapist, and I just unload it on her, right. I just… I get it all out. I say all the things I need to say. Sometimes my therapist doesn’t even say anything. She just sits there while I’m just rambling on about like… You know what I mean? I just close my eyes and I just say it. I just get it all out. And then I feel better that I’ve said it to somebody, that I’ve gotten it out of my own body.

BB: That’s it.

JR: That’s it. It’s amazing. [laughter] It’s amazing.

BB: It’s like magic.

JR: It is, it is.

BB: Yeah.

JR: So I’m all about it. Everybody listening, find you a therapist. And it’s hard, because the other thing is that there’s not always… Unfortunately, we don’t always have access and equity around mental health.

BB: Accessibility. Yeah.

JR: And accessibility. So, I say that cavalierly, but the truth is that it’s not always so easy.

BB: It’s not.

JR: And in times of COVID it’s even harder because everybody is trying to get some help, because everyone needs it. So I don’t want to be too flippant about that, but I do want to say, “If you can, and if you do have access, and there are sliding scales and there are all sorts of ways to do this, but if you can, don’t be afraid to go get you somebody to talk to”. Ain’t nothing better.

BB: Yeah, and I really think in terms of social justice and activism, man, if we could just get more people in front of therapists.

JR: Yeah, man.

BB: Just to stop the causing of the trauma and to heal the trauma, it would be incredible.

JR: And try to find you a therapist that’s good for you. We should also be clear about that, Brené, because we both know how this goes. We’re like, “You got to shop for the right one”. They’re not all going to be for you. Some are going be crazy. [laughter]

BB: Oh, my God, let me just… Yeah, let me tell you that, I saw a therapist for a long time. She retired; it was devastating to me. I went to three or four. She’s come out of retirement and sees just a very selective number of people, so I’m back with her, but I always tell people, “You got to try it on. It’s got to be comfortable like a good pair of shoes, because it’s a long ass walk. And you’ve got to try it on,” and listen, there’s nothing wrong with saying, “I’m interested in a free consult for 20 minutes. I’d like to see if there’s a connection to see.” because that’s part of it. It has to fit.

JR: Yeah.

BB: All right, let’s talk about this new book, Ain’t Burned All the Bright.

JR: Yeah. Ain’t Burned All the Bright. So proud of it.

BB: God, you should be proud of it.

JR: Thank you.

BB: People are losing their minds about this book. Let me see, I’ve got BookList starred review. Those are hard to come by. “An important combination that expresses the zeitgeist of a troubled time. Essential reading.” Kirkus Review, starred again. Holy crap, y’all just don’t even know, these stars are hard to come by. Listen to this. “A profound visual testimony to how much changed while we all had to stay inside, and how much painfully, mournfully, stayed the same. Artful, cathartic, and most needed.”

JR: Yeah. Yeah, to hear that stuff is humbling and is overwhelming sometimes, because you don’t know as a writer if what you’re feeling is what we are feeling.

BB: Oh yeah.

JR: You don’t know. You just try to be as honest with yourself as possible in any given moment, and when it works, there’s this theory I have a tattoo on my hand of the number 26. I look at it often, because it’s right there. So I see it all day, every day, and it represents the letters in the English alphabet. And the reason that I got it is because I think about the letters of the English alphabet as sort of the tools for alchemy. Have you ever thought about that, all we really have as writers, besides spirit and imagination, are 26 letters…

BB: Yeah.

JR: To somehow rearrange in sequence. That could potentially change the way a person moves through the world. It’s the wildest thing. I take it so seriously, because I find it to be so magical. And so when I look at this book, Ain’t Burned All the Bright, people are looking at it as a poem, but honestly, if I showed you my notebook, it’s actually three run-on sentences. I wrote it… Just three sentences that I removed the punctuation from after it was written. It’s just three sentences. Three sentences, right? And I did it this way, one, because this is all I had. This is COVID. I couldn’t even drum up the energy to write. I couldn’t find… We all were struggling to read and to write and to concentrate and to discipline ourselves. I wanted to lay on the couch and just chill and be sad. You know what I mean?

BB: Yes.

JR: It was a tough time. And so I had three sentences in me. One about the racial uprisings, one about COVID, and one about the fact that the only thing that’s keeping us alive are the mundanities. The banality of our lives. Isn’t it an incredible thing to learn that the boring bits are the most beautiful?

BB: Oh God, yes.

JR: And that’s what is saving my life every day. I will tell you the most devastating thing to experience in COVID was my father dies in December, from cancer and not from COVID. My father dies in December of 2020, and I cannot hug my mother. She cannot console me, because I can’t risk her getting COVID. And in that moment you realize, “Oof, a hug is no small thing.” It’s no small thing. We take it for granted, but that embrace is no small thing, when you really think about how much you need it. And that’s what the book is about. I get it. It’s a tough time, but if you’ve got a crumb snatcher screaming in the background, that means you got a child alive. This is what the book is all about. I don’t know what to call it. You’re right, I don’t know what it is. I don’t know what it is. Some people say it’s a manifesto. I don’t like that. I don’t want to look at it… I don’t think that’s it. I don’t know what… If anything it’s a testament.

BB: You know what came to my mind? I don’t know if there’s a word for this, but… There’s a noun for it, but… It’s bearing witness. This book is bearing witness to me.

JR: Absolutely.

BB: And not just the words, but the images.

JR: Absolutely.

BB: When your words say something hard, I found myself fucking terrified of turning the page, because I knew whatever art was on the next page would be crumbling to me.

JR: Yeah, yeah.

BB: Do you know what I mean?

JR: Absolutely.

BB: This book, I felt like it beared witness to my experience of the last couple of years in a way that nothing else has.

JR: Yeah, I appreciate… I mean, that’s big. Thank you for that. And I want to make sure I shout out my brother, Jason, Jason Griffin, who is the incredible artist, and one of my best, best friends who we’ve worked together for 20 years. And it comes from us, our friendship, our relationship. It’s a basic conversation we were having, where he’s like, “Yo, Jay, I’m in therapy, and I’m talking to my therapist. My therapist is like, ‘Yo,'” trying to help him process, and then a mentor advises, like, “Yo, keep a notebook with you, and jot down little pictures. And when you’re on the train in New York or in whatever you’re doing, just sketch in the notebook,” and he said, “I’ve been doing that, Jay, every day, and it’s kind of been like my oxygen mask. It’s kind of been like where I’m finding my air.” And then I say to myself, “Oh, that’s it, that’s what we’ve been looking for. That’s the way to describe it, every single thing in the year 2020 is attacking the respiratory system”. And when I say the respiratory system, I mean, the physical respiratory system, the social respiratory system, the emotional respiratory system. Like, if it’s George Floyd… The way George Floyd’s… The way he dies…

BB: Oh God.

JR: It was through strangulation. The tear gas in the street attacks the respiratory system, the wildfires in California attacks the respiratory system, COVID happens and attacks the respiratory system, everything is attacking breath. And so when he says to me, “This has been my oxygen mask”, all of a sudden, I’m like, “oh, oh, there’s the language.” This is what it is that we’ve been all trying to figure out. The other thing that this book does, Brené. And this is sort of the subliminal, sort of the inference and the implicit parts of anything that I’m working on is always like, “How can I sort of knock at the back of the mind”? You make it think for the front of the mind, as they’re reading it. But how can I also make something that scratches at the back of their mind? The other premise of this book is that, anybody who has had a child who has gone through the crying spell where they can’t breathe, what we tell that child is, “calm down, let’s take three deep breaths.” And so the book is sort of structured as three breaths, because it’s meant to say, “let’s try to figure out if we can find some equilibrium.” Yes, I know, it’s not our normal time, but it is now. But it is now, and I know, we like we don’t want to think about it that way.

JR: Because it hurts too bad. But for the time being, I’d rather look it in the face. Right now, this is where we are, right? So I’m going to take three deep breaths and figure out… As somebody with anxiety, Let me take three deep breaths, and get myself sort of back to level so that I can look at what it is in the face, and also figure out how to save my life by acknowledging the things around me that I still do have, that have not been taken… And that’s what the whole, sort of thing is… Hopefully will do. That’s what it’s meant to be. But we’ll see.

BB: I’m so moved by it.

JR: I’m just glad you read it.

BB: I’ve never shared this with anyone. So it’s weird. And my sister is in the room with me right now, she helps record, so I’m not going to try to look at her because I know she’d be like, “do you want to share that or not?” But in the last couple of years, I’ve developed a massive fear of not being able to breathe. And when I was reading the book, I could feel it. And I thought at first it was, was it just George Floyd? Which is enough…

JR: More than enough.

BB: More than enough to make you to make you think, like, breathe. Just how can you steal… To steal someone’s breath is maybe not only the cruelest, it is just the underbelly of humanity. And then my death fear of getting COVID. And I might not be able to breathe. And then I remember someone asking me in an interview. “If you could do anything right now that you can’t do, because of COVID and quarantine, what would you do?” And I just reflexively answered in a way that I almost had to stop the interview, because I said, “I would crawl on my hands and knees down I-10, just to be able to hug my father”.

JR: Same, same.

BB: Yeah, I needed something to bear witness to this. And that’s what this book does.

JR: We make work. It’s the closest… I hate this analogy, because I know that it’s so far-fetched because I’m not a woman, and I’ll never give birth, and I’ll never come close to knowing what that pain is and what that experience is. But I do know, I’m going to make this terrible analogy, is that it’s a strange thing to conceive of a thing, or to conceive a thing, to carry it, to let it grow, to let it develop, to birth it into the world, to give it a name, to let it grow up. And then move around the world without you and develop relationships with people that you do not know and will never know. And those relationships will be completely different than the one that you had with this child. And the wildest part about it is you don’t even remember the pain of birthing it. I can’t even remember working on it anymore. And it just happened. And I think that’s sort of some of the magic of what we try to do.

JR: I think some of it is ours and some of it is not. I think it’s like a buddy of mine used to say about the radio, he used to say “Man, nobody assumes that there is a band on the inside of the box playing music. People just assume that the music is coming through the thing. Not that there are people on the inside playing it. It’s just a transmitter with it”.

BB: Oh, my God…

JR: And that’s the way it feels for me, in all of my work. But in this particular book, it was like… Because I was hell-bent on not writing about COVID. Everybody knows that right now and it was like a no, no, everyone’s like, “nah… ”

BB: Yeah, yeah, I know, yeah for sure. Don’t even reference it more than twice.

JR: Yeah, exactly. It’s like, “Whatever you do, don’t write about it.” But at the end of the day it’s like this is what it is. This is what I have to say. I’m just so glad that people are taking… So I’m glad people are giving it a chance. And living with it and kind of sitting with it and reading it and rereading it and thinking about the language and thinking about the images and thinking about the conversation those two things are having with one another, because it’s not illustrated. That’s not what’s actually happening…

BB: No.

JR: We just work in an industry where they got to categorize everything. Everything that’s art is like an illustration. But this is not an illustrated book…

BB: No.

JR: It’s more… It’s like the art and the texts are in conversation.

BB: Yeah, and they’re pulling each other…

JR: Absolutely.

BB: And they’re pushing each other, and they’re fighting, sometimes…

JR: Yes.

BB: And creating a tension that is like, “Fuck, I’m putting this down”, and then they sweep you away in tandem. And then they… And it’s just infectious…

JR: Exactly.

BB: I mean it’s… It’s poetic.

JR: And that’s what it’s meant to do. Yeah. And I had a friend who read it. And she said, Jason, “I can’t stop crying. And I don’t really know why, I don’t even know what’s happening, all right but I can’t stop crying about this. I’m reading the book, I’m flipping the pages. And I can feel things happening in my body that are causing me to be emotional. And I’m not sure I understand why”. And I think that is what the book is meant to do. It’s meant to sort of be something that is here in the front of the mind. And also here in the back of the mind. She doesn’t have any idea why because we’re good at pushing things back. Like, we’re good. We’re like the masters of deflection, the masters of…

BB: Yeah I mean. Yes.

JR: The masters of denial, the masters… I mean, I said, “oh my God, the human race, is so good at running”. You know what I mean? We run so well…

BB: Hiding and self protecting… We got that shit nailed.

JR: We got it down pat. And I think sometimes… I hate the word trigger, because I think it’s been overused, but I do think that there are things that sort of access parts of ourselves that we can no longer access.

BB: I think this goes back to Frederick Douglass, that goes back to the power of aesthetic force. That grabbing the prefrontal cortex at the same time you’re grabbing the amygdala, and…

JR: Exactly.

BB: When both of those things are there, you can’t deny what’s happening in front of you.

JR: I’m glad you know these scientific terms, because I ain’t know what they were called, but now I know, the prefrontal cortex and the amygdala, see now I know.

BB: Yeah. This book… Full contact sport.

JR: Absolutely, absolutely.

[laughter]

BB: You better not play with this book until you come back after your sophomore year… Like in high school.

JR: Exactly. You’ve got to be big, you’ve got to be big.

[laughter]

BB: You’ve got to be giant. All right. All right, we have to go to the rapid fire and I’m so excited. Okay, I have to ask this one question, then we’ll go to rapid fire, we’ll go really quick. I don’t want to take more of your time. I feel so much rage and grief around the censorship that’s happening to books.

JR: Mm-hmm.

BB: I don’t want you to deliver me from that rage and grief, because I think I should hold on to it, and I don’t think you’d have any intention of doing that.

JR: Right.

BB: But… You are the national ambassador for Young People’s Literature. This is from the Library of Congress. They’ve extended your role for another year, first time in history. And you got books on a banned list.

JR: Mm-hmm… Mm-hmm. Yeah.

BB: I mean, we’re that afraid, aren’t we?

JR: Of course.

BB: As a country.

JR: Of course. There are lots of ways to talk about this, but here’s what I’ll say in a succinct way. If we were to go into any store, or if you heard about anybody going into a store, particularly let’s say a grocery store or a clothing store and stealing a shirt, snatching a shirt off the register, taking a pair of pants. After you get over the fact that a person has committed a crime, the next thought is perhaps the person needed the shirt or needed the pants. They took what they did not have. So if there are adults who are taking information, taking truth, taking opportunity for discourse and growth from our children, it’s usually because they’re taking it because it is something that they do not have. And that they did not have. That is the only way that I can think about this in a way that helps to quell my rage enough to get my work done.

BB: Yes.

JR: Right? I look at this from a place of… Despite it being despicable and absurd, and I feel terrible for the young people who are being robbed, but the truth is that I know these kids. Right, and because I know these kids, I almost feel more sorry for their parents and the adults. I almost feel like, man, it’s unfortunate that you don’t know one, the power, intelligence, integrity, and promise of your child, and if you don’t know it now, in this moment, you may never know it.

BB: You may never know it.

JR: And therefore, you are robbing yourself. You’re robbing yourself of the potential masterpiece that you had a part in creating. Which sounds so foolish, right? And two, I wish they understood that this generation, because of technology, because of the internet, because the world is so tiny now, it’s really difficult to keep too much from them.

BB: Yeah.

JR: So you can take the book, but you can’t take the conversations they have on the internet when you’re not around. You can’t take the fact that they’re reading about this stuff. And it’s easy when people say, “Well, kids just believe whatever their parents say”… Even that is a little dismissive and belittling.

BB: I think it is.

JR: Absolutely, as if we all weren’t children… I tell my mother… I love my mother. She gave me so much. But there are lots of things that I got older and realized that I had to sort of rearrange. Because what she gave me is what she could give me to get me further than she ever got. But once I got further than she ever got, those rules no longer applied, because now I was in a territory that she’d never been. So how could she give me the game for that territory? I’ve got to create new rules for myself and push the trajectory forward. These young people will do the same, if the rest of us do our jobs. They spend more time outside of their home, their friends, and specifically their friends will be bigger influences on their lives than even their parents.

JR: So if momma and daddy say no, the truth of the matter is there are a lot of people there to reinforce what’s necessary and where we’re moving. And I truly do believe, Brené, as somebody who has spent an awful lot of time with young people in America and around the world, that the majority of them are interested in making the world more peaceful, more equitable, fairer to all the identities that can exist within a single body, to saving the planet, right? You throw a bottle on a ground in front of a kid and see what happens…

BB: Oh, yeah.

JR: They don’t play…

BB: Well, I mean, drive by smoking a cigarette…

JR: It’s a different thing.

BB: My kids used to be like, “stop smoking.”

JR: Get a pronoun wrong, get a pronoun wrong.

BB: Yeah, yeah.

JR: Like it’s a different thing, right? And so, am I mad? Yes. Am I concerned? Of course. But has it stripped me of hope? Nah, these babies… They’re resilient and persistent, and adults can continue to allow their inadequates and insecurities to get in the way for as long as they can, but the time will come where they won’t be able to anymore. Babies grow up. This is what happens. [chuckle] This is what happens. And that’s it…

BB: That’s the given.

JR: It’s all I got for you. You know what I mean?

BB: Yeah, no, I mean… I think the thing they’ll remember, I thought about this the other day, is they will ultimately read Jason Reynolds and Toni Morrison and others, and then what they’ll remember the most is not only what was in those books, but how hard their parents fought for them not to read them.

JR: Exactly. Why would you keep this from me?

BB: That’s the heartbreak.

JR: That is the heartbreak, and it’s a heartbreak that their parents are going to have to deal with. [chuckle]

BB: That’s right, yeah. All right, are you ready for some rapid fire?

JR: Let’s do it.

BB: Fill in the blank for me. Number one, vulnerability is…

JR: Everything.

BB: Number two, you’re called to be super brave, but your fear is real. You can feel it in your throat. What’s the very first thing you do?

JR: Think of my father.

BB: Next, the last TV show that you binged and loved.

JR: All the way through it would have had to been… What is it called? The School of Chocolate? You ever seen that show? That’s the best show I ever seen, hey, that show was amazing.

BB: What’s it on?

JR: It’s on Netflix, it’s like one of these baking shows, like a competition where they make architectural structures with chocolate, it’s really like…

BB: Are you being real? Or are you…

JR: No, no, no, I’m being serious. Chocolatiers are next level genius, I promise you, it’s really something to see.

BB: Okay. I will watch it, because I love all the baking shows.

JR: You’ll love this one, I promise.

BB: Favorite movie?

JR: Oh, so many movies, if I had to pick one, it’ll probably be, Do The Right Thing. But I got a million, but I would say, Do The Right Thing.

BB: A concert, you will never forget.

JR: Oh, probably… I saw Richie Havens in the park, years ago, before he died. Amazing. [chuckle]

BB: Yeah, that’s amazing that you can… Yeah, Favorite meal.

JR: A Whole fish, a branzino or a snapper, in any… Prepared in any way, fried, grilled, roasted, stewed and any green vegetable, and with all the vegetables, they all are equally as good to me.

BB: You with all the vegetables?

JR: All the veggies. I’m all good.

BB: Okay. What’s on your nightstand?

JR: My father’s devotional, he bought one of those yearly devotional… Was those Max Lucado joints.

BB: Yeah, yeah.

JR: But he never re-upped it, he read the same one every year and just tabbed it, and he put tabs and tabs… So I have his devotional and all of these tabs over the course of all these years. And you could can see which one’s he kept going back to, and my father has passed on, and it’s just the most… And I don’t read it, I just have it with me. And it means the world to me. So that is on my devotion… I mean on my nightstand, and then a ton of books, I always keep books and collecting the poetry, notebooks, all kinds of crap like that. You know what I mean, stuff like that.

BB: Wow, that devotional sounds like a window into his soul.

JR: It is, and it does good things for me.

BB: Wow, okay, a snapshot of an ordinary moment in your life that gives you true joy, just a moment.

JR: Whenever my mom opens the door, when I go to my mom’s house, that moment she opens the door, it’s great every time. We’re always so happy to see each other, every time. [chuckle] every time.

BB: So going to your mom’s house, but… Okay, tell me one thing you’re deeply grateful for right now.

JR: You.

BB: Mm-hmm, God dang.

JR: This is wonderful. I’m so grateful for this moment.

BB: Thank you. All right, you gave us five songs you couldn’t live without, I’m going to tell everybody what the songs are.

JR: Okay.

BB: Ready? “Young Gifted and Black” by Aretha Franklin or Donny Hathaway, either version. “Talkin’ Bout a Revolution,” Tracy Chapman, “Vienna,” Billy Joel, “Can’t Knock The Hustle” by Jay-Z and “Slippin’ Into Darkness” by War. In one sentence, what does this mini-mix tape say about Jason Reynolds?

JR: What LeVar Burton said about me when I met him, my dear buddy, that I am a black, ambitious, and sensitive.

BB: You are incredible, and I am so appreciative for the work that you have shared with the world for creating that child and letting us meet them and for bearing witness in the most beautiful and eloquent way I can imagine, I’m sending Ain’t Burned All the Bright to everybody I know.

JR: Thank you.

BB: And just thank you for going after the fish.

JR: Hey, always, we can… I appreciate you, thank you for having me and congratulations on your life.

BB: Thank you.

JR: I feel like people don’t congratulate you enough just because everybody sees Brené Brown as Brené Brown today, well, congratulations, it’s a journey. It was a journey for you, and it is a journey for you, so, congratulations to you.

BB: Thanks.

JR: Absolutely.

BB: Thank you.

JR: You got it.

[music]

BB: God, do you ever talk to somebody, and you think… Let me just be honest, as of late, this probably won’t surprise many of you, I’ve just… My faith in humanity is a little shook, I guess is the right word to say. And then you talk to someone like Jason, and… I just kind of this feeling washes over me like it’s going to be okay, and that people are capable of such amazing goodness and amazing art. I don’t know, you can’t give up, I guess. It was just the right conversation for me at the right time, you can find again, Jason at Jasonwritesbooks.com, he’s also on Twitter and Instagram at @JasonReynolds83. We’ll have all the links in the episode page, some exciting news in the book world.