Brené Brown: Hi, everyone. I’m Brené Brown, and this is Unlocking Us.

[music]

BB: Welcome to part two of our interview with Anand Giridharadas, author of The Persuaders: At the Front Lines of the Fight for Hearts, Minds, and Democracy. I think I told Barrett before this, I told you, I thought the podcast will last how long, our recording, like an hour and 15 minutes or something?

Barrett Guillen: Yeah.

BB: Did it last three hours?

BG: Yes.

[laughter]

BB: They’re like, “We’re running out of tape, we’re running out of battery. Our cards are full.” I’m like, “I don’t care. Shut up. It’s so interesting.” I’m glad you’re here. Part two of a conversation about his new book, The Persuaders: At the Front Lines of the Fight for Hearts, Minds, and Democracy. I’m so glad you’re here. Let’s jump into the conversation.

[music]

BB: Before we get started, let me introduce you to Anand Giridharadas. He is the author of the international best seller, Winners Take All, The True American and India Calling. He’s a former foreign correspondent and columnist for the New York Times for more than a decade. He’s also written for the New Yorker, the Atlantic, and Time. He’s the publisher of the newsletter, The.Ink. He is an on-air political analyst for MSNBC. He’s received the Radcliffe Fellowship, the Porchlight Business Book of the Year Award, Harvard University’s Outstanding Lifetime Achievement Award for Humanism and Culture, and the New York Public Library’s Helen Bernstein Book Award for Excellence in Journalism. He lives in Brooklyn. They have two kids. Who is they? He’s married to a total, yeah, drum roll, fan favorite of Unlocking Us and Dare to Lead, Priya Parker. Let’s jump in.

[music]

BB: Welcome back.

Anand Giridharadas: Thank you.

BB: I’m still thinking about your story, how you see the world, your experiences, and how all of that allowed you to bring us The Persuaders. Have you thought about it at all?

AG: I am now. I think, let me put it this way, from when I was first at the New York Times, 2005, foreign correspondent. “Just do the news.” As I told you in the last episode, I wasn’t… Not necessarily doing conventional news, but I was an objective New York Times reporter, calling it the way I saw it. Facts first, facts only. And I left the Times in 2016, September 2016, I was kind of just reorganized out, it wasn’t a big drama, it was just like there wasn’t a new place for me in the thing that was happening. I was so distressed, 11 years. My whole identity was the New York Times, that kind of journalism. All I’d wanted to do.

BB: Oh yeah.

AG: And I had one friend, an Argentinian friend, who was like, This is the best thing that will ever happen to you. And she’s the kind of spiritual seeker who always says stuff like that, but it’s not true, in fact, something just shitty has really happened to you.

[laughter]

AG: You just have that friend who’s like…

BB: Yeah, yeah.

AG: “Oh yes, you’re about to live this new… ” But you’re not, it’s just bad.

BB: A door has opened.

AG: A door, door has opened. [laughter] Well, it turns out she was right, in a way that I couldn’t appreciate at the time because I had lost this sense of like, “I am a serious journalist in the world, affiliated with the New York Times.” And what happened that September 2016 onward, particularly in a moment that was making it really, really important to be able to speak blunt truths, is that I didn’t have to speak for a large important American institution anymore. I could just say what I thought. And with Trump two months away from winning the presidency, that felt like a really important time to have that power and voice, and I made use of it, suddenly, kind of newly liberated, to say what I thought, called them the way I saw it. And it started me down a road of becoming much more of an advocate than I think I intended to be, than I think I wanted to be, than I planned to be. I think if it were not for this exact era we’re living in, I would have very happily stayed in that kind of place where I hide what I think.

BB: Yeah.

AG: It’s kind of what I believe in, it’s not… I don’t feel it’s my place. But living through the rise of Trump and this moment, I just felt like I need to just say things. And so, I went down this road of being a journalist, but being a more vocal one than was my training, being one who… I often felt, frankly, that a lot of my friends, and they are my friends, in the establishment media were kind of failing at saying certain things candidly and bluntly. And so, I may be compensated for that and tried to show a different way, tried to really call out these threats to democracy in 2015-2016, talk about what I felt was happening to the country, talk about what I felt is a threat of political violence and fascism as being normalized in this country, so on and so forth.

AG: And I had some success with it. My book before this one, Winners Take All, was a very… Was kind of, in some ways, a polemical book, but also… It’s still a book through stories, it’s still a book told through other people’s struggles, but had a clear point of view, we should not have billionaires, we should have a radically different social model if we’re going to actually be the country we think we are and have the American dream, not just be something that exists in Europe, but I very much became an advocate, became someone in that mold, became someone who’s kind of… People put a political label on when they characterize me in the media. And I kept going deeper and deeper into it without necessarily loving that I was doing so. I mean now this is becoming a very therapeutic session, but you do this with all your guests, so it’s fine.

[laughter]

AG: If it’s good enough for Viola Davis, it’s good enough for me.

BB: That’s the motto of the whole podcast. Go ahead.

AG: Exactly. And I think with this book, it was kind of the culmination of, I think me thinking more as an advocate who wants a certain kind of world. I’m still a journalist by craft and method, I still tell people’s stories. This book has almost none of my opinions in it, at least explicitly. It is all about other people and how they’re figuring things out and what we can learn from them. But I think I got to a place where I was interested, as an advocate myself, as someone trying to fight for a certain kind of world and doing so openly, in how I can persuade or not, in how I have, I think, sometimes succeeded at certain elements of persuasion, such as provoking and pushing a conversation versus actually changing people’s minds and bringing people in. I feel those tensions every day.

AG: Every time I write a tweet, I am aware that I can craft it in a way that will rally my people or maybe make someone think on another side of some issue. And I candidly have felt that I, in many ways, leaned into the former approach way more often, in recent years. I got really good at riling people up around ideas that I deeply believe in, and sometimes to the point where that kind of dopamine effect of scoring those points, making those… It becomes a world where you’re getting so much esteem from that kind of choir preaching and provocation that you don’t need anything else, and of course, the platforms we spend our lives on are designed to encourage that.

BB: Yep.

AG: And I think what I became attracted to in the reporting for this book is people who were better than me, who were showing up better than me, but they shared something in common with me, which is none of them are milquetoast, mushy middle moderates who just want whatever is the halfway point between two things, right?

BB: No.

AG: Everyone I write about in this book has, the way I do, big dreams for this country, big dreams for the kind of just and equal and thriving future we can have for everyone, but what they all… All these persuaders I found and learned from and wrote about, what they all had, that in many cases I didn’t or that I needed to learn from, was an orientation to doing two things at once. They all are able to stand bravely in the truth of what they believe and reach out.

BB: It’s pretty incredible, actually.

AG: I’m going to say that again, like stand bravely in the truth they believe and reach out. And the reason that combination is important is I think anyone listening to this can think of any number of examples of people in public life or in your life, who are great at outreach, great at making people comfortable and do that at the cost of standing for anything.

BB: Yeah.

AG: It’s easy to be a pleaser in the political realm or in the personal realm, and just be an amoeba. And yeah, you can make people very comfortable, all kinds of people comfortable, if you believe in nothing. I think it’s also relatively easy to stand firmly for things, have real convictions, and we all know these people too, and we may respect them also in their own right, people who really stand for things and who don’t frankly give a hoot about outreach or who they’re bringing along. I have played both roles in my life. In recent years, liberated from the New York Times, I found myself really going in more of that direction of the advocate, the activist, the champion of a particular set of ideas, and I became interested in these people who were somehow walking and chewing gum.

AG: They were standing firm, they were standing for things, they had real beliefs, real convictions, they weren’t willing to barter them away for a smile. But they wake up every day thinking, “How do we get more people in? Who’s not understanding what we’re saying? How can we help them understand? Who can we walk with? What are we not seeing? What are our blind spots?” And I became devoted to the idea of writing a book to offer… A lot of these people are organizers or have an organizing background as their kind of intellectual training. And I became convinced that what I would call the organizers way, like the tao of organizing. In this moment in America, where so much needs to be done, so much needs to be protected, so much needs to be changed, and so much feel stuck, I felt like the organizers way, the persuaders way, may hold the secret to unlocking the future that we need and that we seek.

BB: I can so relate to everything you’re saying because I have been both those things too. And in fact, before I went on my sabbatical, I got off all of social media, I’m still not back on Twitter, so it’s been five months since I’ve even… I don’t even know my password.

AG: There’s a reason you look so relaxed.

BB: Yeah, no, I mean, we interviewed Ben Wizner from the ACLU and he called Twitter a dopamine casino, which I thought was the perfect thing.

AG: Yeah.

BB: And I think the people that are in this book… It reminds me a lot of the research I did for Braving the Wilderness, what happens when you belong to yourself, and you’re still able to make connection with other people, but you don’t betray yourself to do that. When you are one of those people that stand deeply in your beliefs, but also reach out, you take shit from every side.

AG: Correct.

BB: You take shit from every… “How dare you reach out to these people, screw these people. Forget them.” Yeah, so let’s jump in. I want to start with it because it scared me. I’ll be honest with you, I did not know about the IRA in Russia. I thought the kind of Russian bot social media invasion, especially around the Trump election and then the presidency, I thought that was about diluting truth, so that no one knew what was fact and what wasn’t fact. But what really scared me is…I mean you write here that they knew that our cancel, call-out, write-off culture was the great threat to democracy. Is that fair to say?

AG: It is.

BB: Can you tell us the story a little bit for people listening like this was… I did not know shit like this happened, except in the movies.

AG: And what’s amazing is, it’s so different from what happens in the movies. In the movies, think about a movie, let’s start with what we think about happening between adversarial countries. The United States and Russia is long adversarial.

BB: Yes, for sure.

AG: And in 2013, 2014, just imagine these meetings, right, bureaucrats, low level meeting, then goes to slightly higher-level meeting, some recommendations, some memos, and the question that is being debated in Russia, presumably, is like, “What’s some new thing we could do to this big powerful country?” And by the way, in our country, we are also having similar meetings about what’s some things we could do to them? “Could we take out a power grid, if they do this? Could we… Could we do that? Could we sabotage this? Could we do this to their financial system?” So these meetings are happening.

AG: 2013-2014 there is clearly, we know from the outcome, some meetings, some discussions, some memos in Russia, where out of all the tools of sabotage that they could potentially deploy against the United States, all the tools in the tool kit, it comes to the fore that Americans’ culture of kind of mutual contempt and disgust for one another is a more fruitful generative weapon for the Russians than some of the conventional things like taking out a power grid in Denver or something.

BB: How much we’re repelled, the repulsiveness that we feel toward each other.

AG: Yes, and they conclude, rightly, that this is not something that needs to be implanted in us, this is a native behavior sprouting on American soil natively, that merely needs to be fertilized. And they basically plan this massive fertilizer operation of our culture of mutual contempt and dismissal and of writing off, and what they do is through this ostensibly private, not in fact, super private thing called the Internet Research Agency, which sounds bland, they created millions of social media accounts and built some of them into really big accounts with big followings, two of which I write about, Crystal Johnson and Jenna Abrams, a right troll and a left troll. These are real people writing these posts, these are not bots. Bots is a different thing that they also create.

BB: Okay.

AG: But this is trolls. And so these are human beings, like grunts, showing up at an office every day in St. Petersburg, trying to finger the wounds of Americans, that Americans have with other Americans and just make them worse and pick the scabs and inflame our relations with each other. And I had read about this operation. It was in The Mueller report, some people were indicted in absentia. The great lesson in my line of work, it’s just I always read the source material and I know it’s the same in yours. I’d never read the… It occurred me at some point, I’d never read these tweets. I mean they were around, I’m sure I’d seen them the way you…

BB: Right, right, right.

AG: But they were like compiled, someone actually compiled them. These researchers compiled them. They’re just on a website, and I was like, I’m going to read this like it’s Shakespeare. I’m just going to read this like it’s a book. I’m just going to read it. And the way my mind works is like I’m going to read them as characters, so I got recommendations on the best left troll, the best right troll, and I read their tweets through, like a person, like a character who was developed. And I had read so little on anybody actually close reading these tweets. I spent maybe months, four or five months just reading these tweets. In a book that I spent two years on total, but I spent a huge fraction of my time reading these tweets, which seemed very weird at the time. I developed these spreadsheets and color coded. I can match your color coding with my own color coding.

BB: You’re speaking my language.

[laughter]

AG: It was the closest I would ever look to a social work researcher. I had all these different colors and tabs and all kinds of things, and what I basically took away was that the story we’d been told was “Russians are trying to elect Trump” or “Russians are trying to just drive us apart.” And as I really got into what was going on, the way the text was working in these tweets, I really came to this place of like, No, no, no, they’re trying to make us dismiss each other. They’re just trying to make us go, “Ugh, them again,” to each other. And I think my big aha moment in the book, that may not seem as dramatic a thing as I understand it to be, I think my epiphany at the beginning of this book process was as these two scholars from Clemson University I quote in the book, say, “Anger drives people to the polls. Disgust drives countries apart.”

BB: Oh God, yeah.

AG: Anger is actually not a huge problem in a democracy. I know that sounds counterintuitive.

BB: No, no, that’s true. I agree.

AG: The temperature is high right now, we can all agree.

BB: Yeah.

AG: But at the end of the day, we’re talking about your kids versus my kids, your town versus my town sharing… It’s going to get real. I actually think being angry about how we negotiate the future is not in and of itself problematic, I think there’s a lot of space for anger in politics, as there is in relationships and other things. Mutual dismissal, mutual contempt, just disgust. “You’re not worth my breath.” That is the end. That is actually the end of a free society. And when I was reading the tweets, I felt this, you know, when you’re encountering a work of real evil genius?

BB: Uh huh.

AG: I just thought like, oh, this is deep. This is like deep, deep, deep stuff, right? Imagine someone going into a marriage and not convincing one person that the other person did some awful thing or lied to you about something, but convincing a partner, the other person just isn’t worth it. Never going to change. Never this, never… Just not worth it. Not worth it.

BB: Just slow corrosion.

AG: That’ll kill a relationship, right? And that’s what they were doing at scale to our civic relationships with each other. It was brilliant. It was awful. And it got me thinking, it got me really interested in the people who were fighting the other way. The people who were refusing the write-off, who were refusing contempt, the easy stories of contempt, who were refusing dismissal, the people whose idea of democracy flows from the basic notion that if you want to change things, you have to believe in changing minds, no matter how hard, you have to believe in changing minds. And I decided I want to spend the next couple of years in their company learning from them, and here we go.

BB: All right, let’s talk about some of them. I have to just interject this because it’s so interesting. So disgust is such an interesting emotion. Biologically, we’re wired for it to actually keep us safe from toxins. So disgust is a natural thing that we feel when we smell rotten food. And there’s a disgust scale. It’s got really weird questions like, “Could you eat a monkey eyeball?” There’s actually a valid and reliable scale to measure disgust. What’s interesting is when you look at disgust from a psychosocial perspective, not physical disgust toward something that’s a dangerous thing for us to ingest, but just emotional disgust, it is actually the first step of de-humanization.

BB: So the people we disgust, we eventually de-humanize. When I was reading this, and I was reading about the Russian journalists that infiltrated the St. Petersburg kind of troll factory and how the damage it was doing to the people working there because it was so disheartening what you could do to people and how effective it was, I was just like, “God, could you imagine… ” And just, again, to bring it down, like you do this a lot I think in your work, and I think I do the same, is we look at systems as systems, like whether you’re talking about… And you’ve probably said it three times in this episode, in the first episode, whether you’re talking about a country, you’re talking about an organization, you’re talking about a couple or a family, think about the Gottmans’ research on couples, they can predict 90% accuracy observing a couple. What is the very thing that is the greatest predictor of separation or divorce in a couple? Contempt and disgust. I mean, this was like a sophisticated assault.

AG: Incredibly. Knowing, insightful, empathetic, built on a real understanding of our weakness and a real understanding… I mean, given that Russia is not a meaningful democracy, it’s kind of incredible how insightful they were about the behaviors that make a democracy work or not work.

BB: Yeah, and you made a point in this kind of introduction, which I thought was so persuasive to start with the fact that, “Hey, this is not my analysis of where we are. This is what countries are using to divide us.” They did not instigate this. They amplified an already existing issue.

[music]

BB: All right, let’s start with… Okay, I have favorite things that I’ve learned that kind of freaked me out, blew my mind, changed me, persuaded me, under each of these folks that you talk to, and you do talk to a lot of organizers, some who I know and I think are doing incredible work. And I’ll tell you, there’s a social work principle that permeates this book, which is as a social worker, starting where people are. And so Linda Sarsour, organizer, amazing person. One of the things that you talk about, one of the learnings from this chapter on her, I love that we talk about Lakoff later because this metaphor was so helpful for me, she makes a point, and I’m going to kind of just edit a little bit as I’m saying, she talks about, when we talk about political change, economic, social change, a super highway to progress with too few on-ramps.

BB: Here’s your quote, “She was conflicted about the matter because she deeply believed in where the superhighway was going, believed in these efforts to make the society more inclusive. She just worried sometimes that the way of going about it created barriers to entry for a movement that in fact needed growth if her communities were to be safe and to flourish.” And so, here’s a quote, and I’m quoting Linda here, “When we’re like the heteropatriarchy, when we use those terms, if my immigrant mom in Sunset Park doesn’t know what that is, that’s not going to move her. Or we talk about cisgender people, I get it, I get what you’re saying, I understand that it’s important, it’s an important concept that we need to get through, particularly to make sure that people who are trans and people who are gender non-conforming and others feel whole in space. They deserve to feel whole. I also believe in this idea of mass mobilization and meeting people where they’re at. And a lot of people in our community are not there yet. A lot of white people are not there yet.” You write that her concerns with these barriers are pragmatic, that they turn away potential customers of the future that she wants to live in.

BB: So I think one of the things that these activist share in common is actually a vision of the future that I believe in personally. And I want to be on the superhighway to getting there. And sometimes I’m like, “Screw the on-ramps. We’re moving fast, we’re clipping along an on-ramp. That means I’ll just slow down, use my signal, get out of the oncoming lane, make sure the people get on.” It’s slowing down my superhighway to progress. What did you take away from that metaphor of more on-ramps for a superhighway to the vision of how we want to live?

AG: I love that question. I start with this chapter with three activists. She’s the first. And the reason I chose them was partly because no one can dispute, in the case of Linda and the two others, no one can dispute their level of commitment…

BB: No.

AG: To the destination.

BB: No. They help draw the picture of the destination. They built the superhighway.

AG: No one’s ever called them milquetoast, no one’s ever called them moderate, mushy, middle…

BB: No.

AG: Third way, triangulation… These are people whose credentials, as wanting a world of radical equality and inclusion, are unimpeachable credentials.

BB: 100% agree.

AG: And so, when the three of them, starting with Linda, say, “I’m concerned that our movement is hard to get into, there’s not enough of these ramps,” it is not coming from a place of criticism, of wokeness, or this kind of sometimes empty criticism of cancel culture, which is really a criticism of consequence culture. It is saying, if we in fact want a future in which we’re living quite differently than we are now, in which a whole bunch of people are counted and included in their humanity who are not counted and included in their humanity now, we’re going to have to move a lot of people’s consciousness. The same way labor unions throughout time, they’ve had to just do a lot of political education to get that wage increase down the road. The wage increase was the end of the project, years and years of political education. The way the women’s movement had to do years and years of consciousness moving with women who may have been housewives in the 1950s, who could then over time be mobilized into a very different place and very different set of demands.

AG: Linda was, I think, sounding an alarm that if we are so focused on the destination of the kind of America we want, the kind of world we want, and not attentive to whether it is easy or hard to sign on, whether we are coming across as accessible or intractable, we’re going to lose, and our kids are not going to be safe if we lose. And I learned so much from that notion. In another moment, she says, “You know, the movement I’m in, it feels like a prison where you have to get through four doors to get in. You have to first go through the first door, then it closes and the second one opens, and so on and so forth.” If you’ve been to a prison, you know these doors.

AG: And she said, “You have to know the right terms. You have to show up in this right way. You have to not speak when it’s not your time to speak. Speak when it’s your time to speak. Say this, say that; whatever.” If there’s so many rules to be part of a movement for a just future, there’s just not going to be that many people coming in, she says. And again, this is not a critique from those who don’t want to live in an egalitarian future. This is a quote from someone who has dedicated her life to living in this future.

BB: Wakes up every day and does it.

AG: All she does.

BB: Yeah, at great costs.

AG: And she’s concerned that people are coming into the movement by the tens and hundreds instead of by the thousands and millions. And she, like so many of the organizers, the persuaders that I write about, she has a plan to fix that.

BB: I’m going to have a terrible confession moment here. It doesn’t matter as someone who studied belonging for 20 years, this is true of every environment where belonging is important. There are artifacts and traditions and language that absolutely are used and shared to build a sense of belonging and cohesion, and they are also absolutely can be fashioned into weapons to punish outsiders. And I am guilty of doing that around language as an academic. I mean, come on. My language choices are unlimited in how to exclude people. Half the time, I don’t know what the shit means, but I know that it’s a big word, and it sounds important. But I have resorted to that in times where I felt my argument was weak, I didn’t feel like listening, I was emotionally hooked by something, I couldn’t stay in my skin. I pull out these words to make sure you know you don’t belong here. And God, I just read her work and I thought, “She’s someone I really respect,” all the women in this chapter, Alicia, Loretta Ross. I mean… I want to talk about… I don’t want to replace ideas. I want to displace ideas. Tell me about that.

AG: We were talking about persuasion, and I was trying to learn kind of at her feet about what she’s done as an activist for decades. She’s kind of the most senior of the activists that I write about.

BB: Probably five decades, right?

AG: Yeah, maybe six. She’s in her 70s, but she started young.

BB: Maybe six. Yeah.

AG: And at some point, we were talking about that, and she was giving me the kind of strategy she uses, and she’s someone who in recent years has really, again, as an incredibly credentialed and serious radical activist, but she’s someone in recent years who has talked a lot about, we got to stop with the calling out and build the capacity to call in as a movement, again, in order to win, to get the future we seek. These women that I’m writing about, they’re very idealistic, but they’re some hard-headed pragmatists too, and they have the ability to be both those things. And so she’s talking to me about that. And maybe I said something about, how do you replace… Something. And she kind of reacted, and she was like, “No, you can’t change what people think. You can’t go in there trying to replace the belief they have with the belief you want them to have,” whether it’s your climate denier…

BB: Damn it. Yeah.

AG: Aunt, whether it’s your son-in-law who just came into your family, talking all kinds of madness about crypto or whatever, you can’t replace with your agenda, with your beliefs. What you can do is displace, dislodge. The difference is, if I’m coming to you and you have a certain view about trans people, and I just think you need to expunge that old-fashioned view of trans people and adopt my view, which is that trans people are people deserving of dignity like everybody else, if the way I’m coming to you is with an agenda to just kind of pull out, remove the little piece of your brain that feels that and put in a little piece of my brain that feels what I feel, obviously, your guards are going to go up. Your guard’s going to go up. Your defenses are going to go up.

BB: 100%.

AG: It doesn’t work. We all know it doesn’t work.

BB: It’s actually neurobiology.

AG: Yeah.

BB: It has nothing to do with your level of persuasive ability. It’s actually neurobiology. You’re threatening part of how I see myself.

AG: Correct. And a system that I’ve gotten to work for myself, even if it’s bad or flawed or full of things that even I…

BB: And hurts other people.

AG: Correct. An approach of displacing rather than replacing, I think in the terms in which she and I were talking about it, is, can I plant a doubt in your head, dislodge slightly your certainty around that? And the best way to do that, and this comes up in multiple chapters, she’s one of the people who talks about it, I talked to a couple of disinformation specialists who talk about the same thing in a different way, can I pit something else going on in you against that view you have? You’re not comfortable with trans people. However, you fancy yourself a champion of the underdog. You think you’re not someone who stands with the powerful. You cheer the Mets. You like the Mets. You’re an underdogs person. Well, building that part of you up, making you more aware of that part of yourself, as Beyonce says in her new album, “I’m contradicted.”

BB: Mm-hmm.

AG: Getting you to stand with your own contradictions around it, getting you to realize that your contempt for trans people is in conflict with your sense of yourself as a champion of underdogs, the person who takes the side of the less powerful in a situation, that is displacing, that’s destabilizing.

BB: That’s cognitive dissonance.

AG: Correct. And it’s also walking with you through raising that dissonance, and then the resolution of that dissonance. And we can get to this thing about deep canvassing, which I end the book with. But I think with Loretta Ross, and others, I wrote about that basic notion of, do not come in with an agenda of replacement. Come in with a goal of helping people be more reflective, helping them confront their own internal contradictions and dissonances on a given issue.

BB: I have to say that if you… I mean I love you. I love Priya. I mean and I respect y’all so much. But if either one of you try to replace an idea that I had, I would be unhappy. But God, do I love to have my ideas displaced, because I know at the end of that, I’ll either have more clarity about why that’s my value and why that’s my decision, or I’ll be changed. And I feel like being changed makes me a stronger person. And so I just think this whole idea of displacing instead of replacing is so key to persuasion. Can I ask you just a basic question that I… This is the researcher, language person in me. Can you tell me the difference between persuading, teaching, and manipulating?

AG: Something I thought about a lot, particularly in the chapter I have towards the end on disinformation…

BB: Yeah, that’s where it came up for me.

AG: And cults, and one of the people… I write about Diane Benscoter, she was a former cult victim who then went on to do cult de-programming and is now thinking about, what is a public health approach to 40 million-plus Americans believing QAnon sort of cult on the scale of a small nation within a nation. And she was one of the people I spoke to who was very vociferous about persuasion and manipulation are not the same thing. They involve a lot of the same tactics, but manipulation is, first of all, built on lies and things that are not true. And second, it is for the benefit of someone who is trying to take advantage for their own gain, as opposed to trying to call you towards something better.

AG: Look, and I… Are there borderline cases where it’s going to be complicated to decide, is that persuasion or manipulation? Sure. But I think to me, the important point here is that you were talking about the kind of world you want, the kind of America you want. I think a lot of the forces arrayed against the kind of world you want where everyone can thrive, whether it’s persuasion or whether it’s manipulation, are very interested in those two things, are very interested, as I was saying earlier, in what an emotional and psychological lens can tell us, are just fundamentally interested in the terrain that I’m writing about in this book. And I think the people who want the world you and I say we want to live in, the people who are most responsible for ushering in that world, or defending the ideals of that world, I think think the least about persuasion, think the least about the emotional and the psychological, the power of narrative.

AG: If this book has one project, it is to kind of tilt that back in the other direction. I want the kind of pro-democracy, pro-human rights, pro all of us side of the ledger in American life to be smarter about persuasion, to be able to match every bit of manipulation on the side of darkness, with persuasion on the side of light, with true, honest, empathetic, psychologically astute, emotionally attuned persuasion for the greater good. What is untenable is for those who want that better world for all to essentially treat the terrain of emotion and psychology in which so much of persuasion happens as being beneath their brainiac dignity.

BB: This is so shitty and personal for me for obvious reasons. But it reminds me of when I was getting a PhD in social work, and I have a bachelor’s and a master’s in social work, so I’m a social worker, social worker. And I remember wanting to do the specific dissertation work, and it was important and thoughtful and relevant and political and personal because I didn’t see the difference in the two, and I was told that it wasn’t good enough because we needed to be harder and more quantitative, and we were the lesser than to the psychology department, in the psychiatry departments and the sociology departments. And I remember thinking, “I don’t know that we’re the better than, but we’re definitely the equal to because we’re the only people that come to things with a contextualized lens. Why are you… ” It’s almost an over-compensation on the part of the people that hold the ideals that we do, that you’re not going to see us as soft. We’re not going to be stewards of emotional granularity and literacy. We’re not going to do those things. Look how hard we are. Look how hardcore we are. And then you’ve got the side of people who are really dangerous saying, “Oh, wait. We employ armies of psychologists to better understand. If you acknowledge people’s pain and then give them someone to blame for it, you can do anything you want.” It’s really frustrating.

AG: I think now we’re getting to the very heart of this, the thing that is underlying the problem that I’m trying to correct with this book. But I think we’re getting, in what you just said, to the very core phenomenon behind the phenomenon, which is that at some very deep level, and I think this has gotten intensified through the age of meritocracy, more and more sorting, people living in their bubbles separate from each other, not knowing other types of people outside their geography.

BB: Yeah. The Big Sort. Yeah.

AG: The Big Sort. I think the brainiac intelligentsia, call it whatever you want, who staff a lot of the influential spaces that stand between us and the apocalypse, a lot of the movement, causes, the offices that are supposedly fighting in defense of the world you and I say we want to live in, at the end of the day, do not respect appealing to people on the level of emotion and psychology. I just think they think it’s an area of life that they are above.

AG: And I don’t think you need to look much further than the ads they make, or the policies they propose, or the speeches they give. I don’t want to put you on the spot. I would be curious, and I don’t want you to answer this because this is personal, but I’m almost certain, although you get so many phone calls from so many people, I’m almost certain that some of the people I most wish would call you and who I think you could really help, have not called. That would be my bet. Maybe I’m wrong. The people you could help give this lens to, have not. I’m sure a whole bunch of people have called you, but the people who most need to, I would be surprised if they’ve actually called you and been open to you helping them think about this. Here’s the really scary truth to me, catering to people’s emotions and psychology, as you know, is a morally neutral skill. It can be used for good or evil.

BB: 100%.

AG: And the people who want less of us to be included, the people who want women to go back to The Handmaid’s Tale, the people who want people darker than a certain shade to go back to their country, so on and so forth, they start their political advocacy with what’s going on with you. What are you feeling? What are you afraid of? What are you anxious about? They do not show up in people’s lives with the policy agenda leading.

BB: Never. No, they tap into fear.

AG: The tapping into fear is like one step later, like putting a value judgment on it. I would just say even before that, like, cognitively, what they’re interested in.

BB: Oh yeah. Where are you?

AG: Where are you?

BB: Yeah. Where are you? What are you feeling?

AG: It is a user-centered politic. How wild is it that the most dystopian, anti-humanization, anti-inclusive forces actually have an instinct and a practice, and as you’ve said, hundreds of psychologists or whatever in their… on their team, to start with, “what are you going through?” And then they might gin up the thing you’re feeling, which is visceral and guttural and based on the immediate stimuli in your life. Like, no one is feeling a thing about a alien invasion on the southern border, that’s not how people start. People don’t go to a 10, people start with like, “I went to Walgreens and… ”

BB: Yeah, I’m packing lunches and putting my kids on buses and… Yeah.

AG: But people are speaking Spanish at my Walgreens now, it makes me a little uncomfortable, that’s how it starts to people. That’s how actual politics are. And the forces of darkness and closure, they understand you’re feeling that. And they then do the meaning-making legwork to get you to a place where you think there’s a southern invasion that’s destroying your way of life. Those who want a more open, inclusive and free America start with, “Have I got an infrastructure plan for… Have I… Brené, I got… ”

[laughter]

AG: I have some solar credit, your whole roof, the sunny side, do you live in a south-facing house? Your whole roof. “ All of this stuff is so important, I love this stuff. But I know these people, they’re my friends, this is a loving intervention of a book, I know many of these elected officials personally. This is not how they think, they know it’s not how they think, they know it’s an area that they’re not good at, they know that they are conceding the country to some very dark forces if they don’t catch up on it, and I believe they can catch up on it, but it requires a complete renaissance in their habits.

BB: It gives me goosebumps, and I will say that, without question, probably one of my favorite chapters was “The Art of Messaging.” I’m just going to have to tell everybody listening, we could talk for seven hours and we’re probably verging on that right now, “The Art of Messaging,” Shenker-Osorio, am I saying her name, right?

AG: Yup, Anat Shenker-Osorio.

BB: Anat, yeah. What a badass.

AG: She is.

BB: God, just the intersection of metaphors and language and emotion and how we use that and how it uses us. I’m going to go to this in the end, I really could talk to you like for 100 hours and maybe one day we will.

[chuckle]

BB: This is a hopeful book, I’m a grounded theory researcher, and there is this ethos in grounded theory where the world continues going, whether we understand it and know it or not, and what I feel like you’ve done in this book is given us a way of understanding about what’s happening that is a celebration of what we’ve achieved and a deep sense of possibility about what can happen. But I don’t think we can shift this path until we understand where we’re walking right now, and that’s what this book does, this book says I know things feel really shitty and hard right now, and it feels untenable and uncertain, there’s a reason for that, we’ve gone through a lot, we’re going through a lot, but there is a path that feels different, and maybe in the end is less energy than the path we’re on. If I had to do it like in a blurb, I would say don’t give up on people. We’re all we have.

AG: It’s a beautiful way to put it. I will say, I got to that place and you’re the cataloger of emotions, I just have them, but I got tired of despair.

BB: Yeah, despair, yeah, me too.

AG: I just got tired of it. I did it for a while. I chronicled other people’s despair, I watched our country go in this direction it’s gone in recent years, and I shook my fists at the TV. I also sometimes had the privilege of going on TV and shaking my fists on TV while other people are watching the TV, shaking their fists at the screen.

BB: I’ve done it, I’ve shaken the fist while I’ve watch you shake the fist. I’ve done it.

[chuckle]

BB: MSNBC.

AG: I did some tweet storms, I got mad at people, I called people names, and I just got tired of the despair. And I wouldn’t be surprised if a lot of people listening to this, I don’t think you and I are the only people who’ve gotten tired of despairing.

BB: No.

AG: And I think at some point, I realize us feeling despair is part of the project of people who don’t want this country to be for everybody, and I’m not going to give them that power.

BB: No.

AG: I’m not going to give them that satisfaction, I’m going to refuse despair, but I can’t do it alone, because I don’t, right now, have the resources not to feel this despair, I don’t have the fact set to justify not feeling despair. And what I didn’t… It’s kind of fitting, I started this book in like March or April, the first year of the pandemic, when I really needed… Like, a new despair was following in addition to the old ones, and I just… I don’t know, I had this deep instinct for needing to spend time with some people who were swimming in the opposite direction, who were achieving what I wasn’t, which wasn’t, as you say, kind of a hope that’s just a sentiment, but a hope grounded in practice, a hope, as you said, that was one of those three components, is agency, people who were deploying their agency who believed in the power of other people’s agency, and who are providing a kind of grounded evidence-based hope.

AG: And I just spent time with them, these persuaders, these organizers, these activists, these elected officials, I spent time with them, including Anat Shenker-Osorio, brilliant, brilliant thinker about how language can help us create that bigger we. And the biggest thing I took away from her and from all of them is that when we sort of accept the frame that all is lost, we start to lose more and more, and when we in fact, remember that politics is supposed to be hard, societies are supposed to be hard, when we in fact remember that what America is attempting to do right now, going back to my family’s origins in this country, is awesome, is literally awesome. We don’t tell ourselves that enough.

BB: No, we don’t.

AG: China and India and France and Germany and Finland are not trying to become nations made of the whole world. I remember when I wrote my book about a hate crime spree in Dallas and white supremacy and hatred was on my mind, given the reporting I was doing, and I remember going up to Plano where white supremacist murderer had spent his childhood, and sitting outside his house, trying to describe it in my notebook and feeling a little bit scared, wondering who lives there. And then I got really hungry as I pulled away from that thing and I was like, “I got to get somewhere to eat like now, otherwise I’m going to faint.” And I remember looking on my phone for the nearest restaurant, and I pull into this strip mall like a minute and a half from this kind of incredibly white and scary neighborhood, and this strip mall was entirely a Korean strip mall. There was no English anywhere, I couldn’t find the restaurant that I had found on Google Maps, and it was like this fully Korean amazing world, this really awesome Korean meal, and I had been in this white supremacist guy’s childhood space in that kind of neighborhood like two minutes before. And that is this country, a country that has that real baggage, has that real history, but also is trying to do something hard. We are falling on our face right now because we’re jumping high. We are trying to build a kind of country that no country has ever built before.

AG: I actually think we’re doing better than we think, we’ve changed more people than we realize, we’ve moved more people into new forms of consciousness than we realize, and it’s going to get real before it gets better. A lot of people are experiencing this allergic reaction to that future, a lot of people are lost, are having stress reactions to it, are willing to burn down the country rather than share it. But I think it’s important to tell the story of what we are trying to do, of how noble a thing it is to try to do what we are trying to do. And to then remember in that context, that if we want that change, if we want to change all those things, we have to come back to changing minds, we have to come back to persuasion. And I think most importantly, because this is not a job we can outsource to others, we have to become…

BB: That’s it.

AG: In our own lives, persuaders.

BB: Yeah, it changed me. It displaced some of my ideas, and then it changed me, so I’m grateful. Thank you.

AG: That means so much to me. Thank you.

BB: Do you have time for a rapid fire?

AG: Of course.

BB: Okay. Let’s go. Fill in the blank. Vulnerability is…

AG: Openness to the effect other people might have on you.

BB: You’re called to be very brave, you’ve got to do something really hard, but your fear is real. You can feel it in your throat. What’s the very first thing you do?

AG: Someone taught me once right before you go on stage, which is where I often experience that kind of thing, right before you walk on, to say to yourself, “Love, love, love.” And then walk out. That’s what came to mind.

BB: It’s beautiful. The last TV show you binged and loved.

AG: I’m in the middle of it, almost done, it’s called The Spy. It’s a Netflix limited series about an Israeli spy who infiltrated the highest levels of government in Syria, Sacha Baron Cohen playing this incredible… And I think it’s a true story. It’s pretty remarkable.

BB: Wow. Favorite movie of all time.

AG: The Godfather.

BB: A concert you’ll never forget.

AG: It was this summer with actually, most of the people I dedicated this book to, we all went together, and a very deep, deep group of friends of mine who became more than friends, but sort of beloveds in the pandemic for a whole bunch of reasons. And we all went to a concert of The Weekend together in New Jersey. And it was one of the great nights of my life, I think I just… I love his music, and I love those friends. I ended the book, the acknowledgements, the last sentence, the acknowledgements is what I kind of learned from those friends that it all kind of felt that that night what I learned from them is that openness opens.

BB: God, that’s beautiful. I’m going to write that down along with my other 500 quotes that came out of this book.

[chuckle]

BB: But openness does open. What’s on your nightstand?

AG: Gosh, I have been reading The Grapes of Wrath. When I was young, I skipped a lot of things I was supposed to read and then just read other things that I was not supposed to read, and so books like that, that I was supposed to read, I didn’t. So sometimes I have to catch up on them. It’s incredible. It is such an amazing way of being an activist and doing art at the same time, something I struggle with. I often feel there’s maybe more of a tension. I just started my friend Min Jin Lee’s book, Free Food for Millionaires, incredible book. I’ve been reading this book, Svetlana Alexievich called Secondhand Time, she’s won the Nobel in literature a few years ago, who does these oral history-based books, and it’s about Russia and the kind of end of last years of communism and transitioning. It’s just such an incredible portrait of what a mass traumatic event it was to have one system snatched from you and the new one not entirely convincingly arrive, and the way people are left stranded. A, it explains so much about Russia right now. And B, it just explains so much about us right now.

BB: Give us a snapshot of an ordinary moment in your life that gives you real joy.

AG: I have always liked cooking, but I think, like many people, the pandemic made it a core pillar of my life. And so, I think a lot of my best moments are my 4 1/2 and seven-year-old running around, my amazing wife, Priya Parker, who has, of course, been on this show eight or 12 times.

BB: Always.

[laughter]

AG: Yeah. Standing around with a glass of wine and cooking. And I live in New York, where one of the great things and terrible things is that you can have any food from any country delivered within like six minutes for relatively cheap, and your kitchens are small, and so the temptation to not cook is great, even if you’re someone who enjoys cooking the way I do. And the pandemic, when that was taken away, I just really reconnected with the power of cooking for people, my friends, my family, my kids, it’s become like I think a bedrock of my life now in a way that it was always kind of an aspiration before.

BB: Wow.

AG: Also, important clarification. It’s also a necessary art in my life because while Priya is the queen of gathering…

BB: Yes.

AG: It’s an important asterisk, as she has explained to you many times, that her gathering skills do not extend to the preparation of food.

[laughter]

BB: She has shared that. She has shared that. Last thing. One thing that you’re deeply grateful for right now.

AG: I’m really grateful. I think some parents are really good with babies and infants, and I think we were… I don’t want to speak for Priya, like we were fine, good, but our kids now at four and seven are really emerging into people like real people, complex, earthy, wondrous people. And I feel like we’re leaving a kind of certain animal phase that we were in, a kind of very visceral and difficult and wordless phase we were in. Priya and I are both words people, she’s a conflict resolution facilitator. She hears other people’s words and plays them back and reconstitutes them for a living, and I listen to people and write words for a living. Our children are entering the word… Words phase now, and people we can have word-based relationships with. That’s what separates us from elephant parent-child relationships, which is sort of what we were in like six months ago.

AG: And it’s beautiful, it’s beautiful to have this kind of connection of words, which you were talking about, about language and the heart, and that shore metaphor that I’ve heard from you to have that with one’s children and to begin to recognize their separateness from you through that. When they’re just the pile of bodily needs, they feel like an extension of you. It’s when they start to talk, and this all comes back to talk. Persuasion is talk. Democracy is talk. When children start to talk, that’s when you realize they’re not you.

BB: No. They are their own meaning makers.

AG: They are, and then they remake yours.

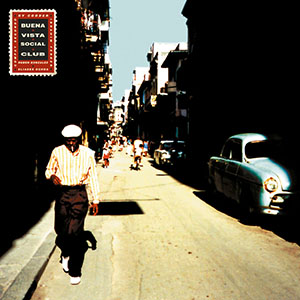

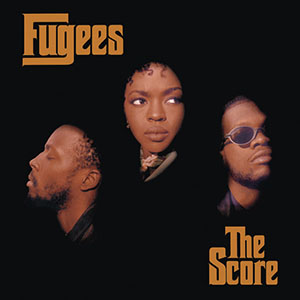

BB: But then they remake yours, and then there’s a period of time that I’m in where they are really good at it, yes, they’re really thoughtful. All right, you gave us… This is our last thing, you gave us a mini mixtape, songs you can’t live without. “In Your Eyes” by The Weeknd, “Vegas” Doja Cat, “Moonlight Sonata” by Beethoven, “Chan Chan” by the… Oh my god, by the Buena Vista Social Club, oh, that song. And then “Killing Me Softly With His Song,” I thought I was going to see Roberta Flack, but the Fugees and Ms. Lauryn Hill. God, that version is beautiful. In one sentence, and I have to say this to all writers and academics that don’t involve dashes or colons, in one declarative sentence, what does this mini mixtape say about you?

AG: I crave it all.

BB: [chuckle] I love it.

AG: It wasn’t one sentence per song. It was just one for the whole.

BB: What’s the collection say? Yeah, I crave it all. All right, y’all, the book is The Persuaders: At the Front Lines of the Fight for Hearts, Minds, and Democracy. And thank you for the book, thank you for your time. So generous with this two-part series. We’re excited about it. It changed me. It really dislodged, replaced, got me hopeful. So, thank you.

AG: Thank you. This is such an incredible conversation to get to have, and I’m grateful for you putting these things out in the world and putting this lens of what is actually happening with people out into prominence in the way you do. I feel like we’re pushing up the same hill.

BB: Pushing up the same hill. You bring the music.

[laughter]

BB: Thank you.

AG: Thank you.

[music]

BB: Okay, this conversation, just I’m so glad you’re with us. You can go to brenebrown.com and find links to where you can get a copy of The Persuaders. You will read this book with your partner, with… it is the most amazing book club read. It’s a great book. I am reading it for a second time, Steve’s reading it, it’s just… I hate to use the word persuasive, but it’s a whole new way of looking at things, which I love. You can find links to everything on brenebrown.com, on the episode page. We are glad you’re here. Stay awkward, brave, and kind. And we will see you for part two next time. Bye.

[music]

BB: Unlocking Us is a Spotify original from Parcast. It’s hosted by me, Brené Brown. It’s produced by Max Cutler, Kristen Acevedo, Carleigh Madden, and Tristan McNeil, and by Weird Lucy Productions. Sound design by Tristan McNeil and Jaimi Ryan. And music is by the amazing Carrie Rodriguez and the amazing Gina Chavez.

[music]

© 2022 Brené Brown Education and Research Group, LLC. All rights reserved.