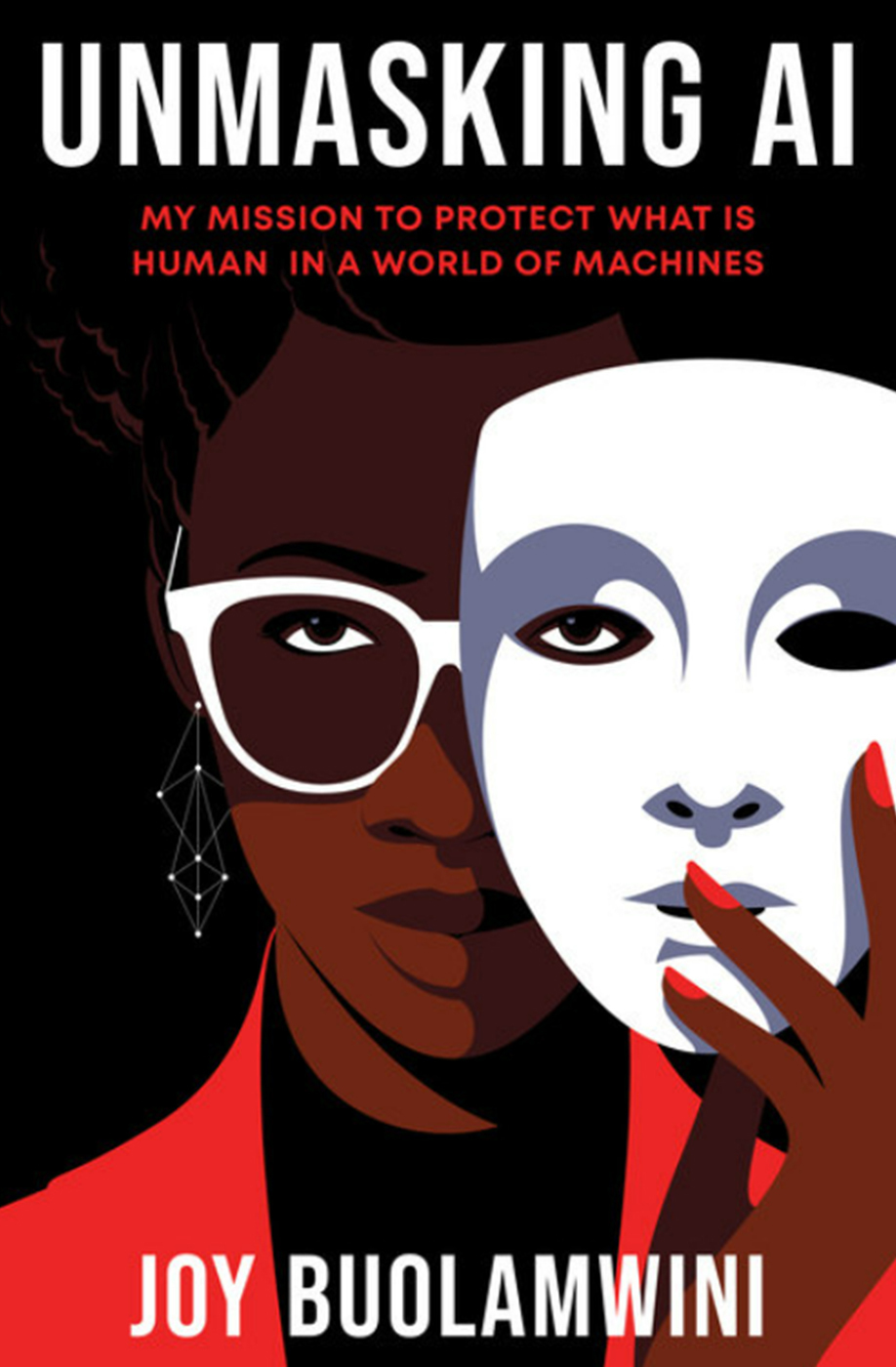

Brené Brown: Hi everyone. I’m Brené Brown, and this is Dare to Lead. If it sounds like I’ve got a big grin on my face, it’s because I have a huge smile on my face. If you do not know Dr. Joy Buolamwini, you are missing out. Let me just say that. I’m just going to draw a line. She’s one of the most amazing guests I’ve ever had the privilege to talk to. We are going to dig into her book Unmasking AI: My Mission to Protect What Is Human in a World of Machines. She’s got every tech bonafide you can imagine. Let me tell you a little bit about her. She is the founder of the Algorithmic Justice League, a groundbreaking MIT researcher and an artist. She is the author of the national bestseller Unmasking AI. She advises world leaders on preventing AI harms. Her research on facial recognition technologies transformed the field of AI auditing, and has been covered in over 40 countries.

BB: Her “Gender Shades” paper is one of the most cited peer reviewed AI ethics publication in the world. She’s got an amazing TED Talk. We’ll link to it on the page on brenebrown.com. She’s a Rhodes Scholar, a Fulbright fellow, a recipient of the Technological Innovation Award from Martin Luther King Junior Center. She’s the 2024 winner of the NAACP-Archewell Foundation Digital Civil Rights Award. She has a PhD from MIT, an honorary Doctor of Fine Arts from Knox College. She’s a poet, she’s a coder, she is light, she is magic, and I cannot wait for y’all to hear this interview. Let’s jump in. Welcome to Dare to Lead, Dr. Joy.

Joy Buolamwini: Thank you so much for having me.

BB: I totally stalked you in your DMs.

[laughter]

JB: You did. DMs have been working out, that’s how the cover of the book got made. I actually reached out to the illustrator, sent her an Instagram DM, and she just happened to have time. She’d seen the documentary, Coded Bias, so she knew a little bit about the work, but it was a last minute request. So Instagram DMs for the win. [laughter]

BB: I wasn’t even shy either. I’m like, “Hey, I love your work.”

JB: I was suspect. I was highly suspect. I said, “All right, let’s double check everything.”

[laughter]

BB: So before we get started, we always start with the same question, but I had to start with telling you how absolutely obsessed I am with your work. I think that I can get out of bed in the morning and face AI because there are people like you in the world asking really hard questions, holding people accountable. I’m just so grateful for you and your work.

JB: Well, I’m grateful to be here and to have the opportunity to share more about it.

BB: So let’s start with your story, and I mean from baby Joy.

[laughter]

JB: Yes. So baby Joy actually popped up in Canada of all places. I was born in Edmonton, Alberta. I was there because of education. My dad was getting his PhD at the University of Alberta. I was born the year he defended, so I really had no choice but to go down this academic path. And so I’m the daughter of a scientist, and I’m also the daughter of an artist. And funny enough, my mom’s dad, Dr. Daniel Dwomoh Badu, so I’m third generation when it comes to this academic tree, actually taught my father, right? So there’s this whole lineage and a few weeks ago, I visited Ghana for the first time in 30 years and I went to the university that he was dean of the School of Pharmacy for. And so it was very nice full circle, because my mother would tell me all of these stories growing up and the places she described I finally got to see in person.

BB: Wow.

JB: And so I’m the daughter of an artist and a scientist. I was born in Canada. When I was about two years old, I moved to Kumasi, Ghana. And so that’s the heart of the Ashanti region and those are where my earliest memories are. I lived with my maternal grandmother and then when I was about four years old, I was reunited with my parents and I didn’t know who these people were forcing me to eat vegetables, but I was told we were related and then we moved to Oxford, Mississippi. So my dad was teaching at Ole Miss. You can tell we were immigrants, because they were calling it Olé Miss, so it was clearly not a… [laughter] Here are some outsiders.

BB: At Olé Miss. Yeah.

JB: You’re right, at Olé Miss. I learned their British English would not fly at school quite quickly, so definitely living in-between cultures. And when I was around 10, we moved to Memphis, Tennessee, so keep that southern, and then went to undergraduate. I studied computer science at Georgia Tech in Atlanta, Georgia. So just despite the very cold start in Edmonton, Alberta kept it pretty warm.

BB: Wow. So Georgia Tech.

JB: Yes. Yellow Jacket, Ramblin’ Wreck.

BB: Yellow Jacket. Yes, we’ve done some Dare to Lead work at Georgia Tech. A couple of my favorite people are there. It’s a really interesting school.

JB: Absolutely.

BB: What were you like and what did you love as a teenager?

JB: As a teenager, what was I like? I was the kid who was skateboarding, who had my electric guitar, and would make up songs and turn up my amp really loudly. And then I was also very athletic, so I was on all the sports teams, cross country, basketball. I did track and field and my favorite event was pole vaulting. The risk taker in me was…

BB: Oh my gosh.

JB: All for that. I used to skateboard. And so that just allowed… Actually, no, the reason I got into pole vaulting was, I was at track practice one day and we were doing pushups. The coach comes around like, “Man, those are some really nice pushups.” I’m like, “Yeah, I got some good pushups.” But he was talking about the girl behind me and I was like, “What? You think her pushups are good?” And so she is telling this girl that she should go try pole vaulting.

JB: So I was like, if you think she can pole vault, then I can definitely pole vault. The thing with pole vaulting is it’s so much more than strength. You have to be a little bit of a daredevil. She didn’t have that daredevil side, I definitely had that daredevil side. So they say it takes the speed of a sprinter, the strength of a thrower and the body awareness of a gymnast. I had two out of three, so that was my thing. So I was just full of energy. Sometimes I would skip basketball practice to be at knowledge bowl sessions, and the coach didn’t know what to do with me because it’s like, it’s quiz ball, you know? So it’s nerdy educational. And so the coach, the knowledge bowl coach and the basketball coach would be trying to say, split time.

[laughter]

JB: I think I was probably more of an asset to the knowledge bowl team than the basketball team to be honest. Vertically challenged here, which, so I like pole vaulting. So yeah, me as a teenager full of energy, exploring all kinds of things, building websites so that I wouldn’t have to pay for my track uniform and my basketball stuff, so I was like, oh yes, I will make some cash. I can barter with these tech skills. So a little entrepreneur, just testing and experimenting and trying many things. Showing up with all my AP books. I remember this. We would go to basketball games and in the locker room, I’d have like AP physics, AP chemistry or whatever else, so I would be doing that homework during halftime. [laughter] So I would have time to get the work done. So yeah, I think that’s probably a snapshot of teenage me all over the place. Having too much fun.

BB: Wow. I mean you are engaged, left brain, right brain, full body contact. You are all in.

JB: Yes. Full brain, full human.

BB: Love it. Okay. Georgia Tech, what do you learn about yourself at Georgia Tech?

JB: Oh, Georgia Tech was such a fascinating experience for me. I came in international affairs, biomedical engineering, then switched to computer science quite quickly, then switched to some other field, computational media, then switched back to computer science and then along the way, started a haircare technology company. I was doing all of these entrepreneurial projects. And so I think the biggest lesson I got from Georgia Tech was finding ways to use my official schoolwork to explore what I wanted to do regardless. So for example, my senior project ended up being experiment really with The Carter Center. And so for my capstone project, I was actually working with The Carter Center. We went to Ethiopia, and we were exploring ways of transforming their paper-based methods of assessing the effectiveness of their campaigns. So monitoring and evaluation at that time, Android tablets were coming on the scene and because they were open source, I could actually program them.

JB: And so I was working with them to program and transform their paper-based way of testing their campaigns for various neglected tropical diseases. So in this case, trachoma, which is an infectious disease that can lead to blindness, but it was actually something there was medication for. So Pfizer had this drug called Zithromax that they were distributing, but they weren’t actually so clear on how effective it was. So they had this MalTra program, malaria and trachoma, where they would go to different villages, distribute it and so forth.

JB: The problem with the paper-based way of trying to assess it is there’s a lot of data entry, and that data transcription is not exact. And also when it came to the locations, trying to put in the GPS coordinates, was not exact at all. And so being able to use the GPS on the Android tablets helped to make it a bit more precise. So for me, this was so exciting because I was motivated to get into computer science to try to use tech for good. And so at Georgia Tech, I found that it was possible to translate these technical skills towards big problems in the world, and make a meaningful contribution. So I think that was one of the biggest takeaways for me. Go Yellow Jackets.

BB: Go. Yeah, I guess I’m in a state of shock because this seems like the progress of a 50-year-old at the Gates Foundation or something. So I’m so amazed that you’re programming these new, and I’m doing the math in my head. So the Android tablets were relatively new.

JB: Yes. This was around 2011, 2012.

BB: Yeah.

JB: Yes.

BB: Okay. Where did you go after Georgia Tech?

JB: So after Georgia Tech, I take a detour, and I do a haircare technology company. Send us strands of your hair, we analyze it, give you unique product recommendations. I’m having a good old time. I get a… My mom saying, “Wait, have you thought about applying for the Rhodes Scholarship?” And I’m like, “Ah, Oxford sounds cold. How about the Fulbright Fellowship?” [laughter] So I applied for the Fulbright Fellowship and Fulbright Fellowship, just like pole vaulting, I was hanging out with some friends one day and they were talking about what they were planning to do for the next year or so. And one’s like, “Oh yeah, I’m applying for the Fulbright.” I’m like, “Oh, she applied, I could probably apply.” I applied. I ended up getting it, she didn’t unfortunately, but she inspired me to apply, so shout out. And then as I was going to do that, my mom was still adamant about applying for the Rhodes Scholarship and I was still, “It’s cold, Mom.”

JB: But anyways, I applied for it and thankfully both came through. So I went to… It sounds like an AI generated story, but this is true.

BB: It does sound like an AI generated story, but keep going.

JB: Right. It doesn’t even sound real, but that’s what happened. So I was in Lusaka, Zambia and inspired by some of the work I had done with The Carter Center and in Ethiopia, I was saying, okay, I wanted to really think through the part that I was playing in trying to use tech for good, because in the situation of working with The Carter Center, I was literally the westerner parachuting in a tech project. And when I did that, I found out that the assumptions I made when I was programming this in my childhood bedroom in Memphis, Tennessee, didn’t actually hold out to the real world conditions.

JB: And I was also wondering, well, why aren’t the local people developing these systems? Why am I coming in? And so with my Fulbright Fellowship in Lusaka, Zambia, the focus really was equipping Zambian youth to make mobile apps for things that they cared about. So we partnered with iSchool Zambia, and we worked on the ZEduPads, which were Android tablets that had the entire Zambian school curriculum on there. And I got to train youth who… It was funny, they’d walk into class. They wouldn’t ever think I was the instructor. So I would learn a lot before class got started.

BB: Oh yeah, I bet. Undercover.

JB: Always undercover. And then I mentioned I used to skateboard. There were Zambian skateboarders there. They would get their parts from South Africa, and then we also found this poetry scene, so I was hanging out with the poet. It was a great time, meanwhile, I was teaching people how to code. And so then when the Peace Corps folks would come in and they would see photos of my projects, they would always be confused, because it’s usually like some white guy and a bunch of Black people out with the fishery. And my photos were all of these dark-skinned people programming apps. So they were like so…

BB: On skateboards.

JB: Right. Skateboarding having a good time. I have to send you some of the skateboard photos and videos we had way too much fun.

BB: Oh my God, I’d love it.

JB: We made music videos. It was a great time. So then after around seven months, it was time to go to Oxford. The second Oxford. Oxford, England.

BB: Yeah, not Oxford, Mississippi. Yeah.

JB: Time for Oxford, England. And so I went there to start the adventure of being a Rhodes Scholar. And I made the mistake of enrolling into African Studies. After the first lecture, I knew I was in the wrong place. In the wrong place. [laughter] So it was just such a disconnect from the work I had done in Ethiopia, the work that I was doing in Lusaka. And they were taking more of an anthropology perspective which is fine, just not where I was at the time. So I quickly switched to another discipline. So I switched to the education department, learning and technology, which built more on the work I had been doing, teaching youth how to make mobile apps that they cared about. And so, yes, just like when I went to Georgia Tech and I’m like, okay, international relations, probably not me. Oxford, African Studies, probably not me. So I got through the first year, it was cool. Then with the Rhodes Scholarship, two years are funded, and the program I did was a one year program. So I had applied to a master’s, I think in public health, global health, because the work in Ethiopia, I had a story. It made sense.

BB: Yeah.

JB: Somewhere along the line, I realized I really didn’t want to do global health. They didn’t like my jokes. It was like a very somber kind of culture. And I’m not that person, so I was like, maybe I should do something else. So I had an idea. So I proposed a year of service where one such scholar, hoping to use their year to make a meaningful impact and fight the world’s fight might instead of doing a course, pursue some other idea. So I pretty much wrote a forty page plea or proposal to describe this year of service, how I would do it, why it was impactful. And then basically, I said, I would do it one way or the other, so they might as well get the credit for it. And it’s been a hundred years, we haven’t changed our way.

JB: They told me not to get my hopes up, but long story short, they allowed me to do it. And so my second year at Oxford was actually teaching Oxford youth how to code apps they cared about. And I used a very similar curriculum.

BB: Stop.

JB: Yeah. We actually did a first responders app focused on campus sexual violence. The limestone at Oxford was just about as impenetrable as anywhere else, so the low connectivity issues also transferred. There was a lot going on there, but so I had an opportunity to do that. And along the way, I get a call from my dad, I mentioned the PhDs earlier. He is like, so what about the terminal degree? Think about graduate school. So I applied to just one place. One, if I… look, I applied to one place. I’ve done what my dad wants me to, I’ve applied to graduate school. If I make it, great, if I don’t, I keep on my entrepreneurial adventures. So I applied to MIT, I get in and then I’m off to MIT.

BB: [laughter] Dr. Joy’s got this whole thing where it’s like, hey, if those are your pushups, I can go to MIT. If those are your pushups, I can be a Rhodes Scholar, a Fulbright.

JB: I’m like, hmmm, it wasn’t on my radar, but I think I got this. Though I mean, to be fair, when I was little, MIT was the dream tech school because all of these documentaries I would watch, it was always the backdrop, such and such happening at MIT. I didn’t know there were requirements, but I was inspired.

BB: You just thought it was going to be a great narrative documentary experience, but it turns out there’s like prerequisites that’s terrible.

JB: Right. Things of that nature.

BB: So you’re in MIT?

JB: Yes.

BB: And you love it?

JB: Oh my goodness. So I am finally at the Future Factory, and I’m there when they’re celebrating the 30th anniversary of the Media Lab. Martha Stewart is there. You have The Magicians. They’re talking about magic and mischief. And I was so excited. I mean, nerd in me could not have been more thrilled. And one of my professors was a Japanese pop star, the design one, there’s this other lady making synthetic estrogen, and she had this project “Sad Bad Chickens.” It was just like I can’t even make up. Like I can’t make it up.[laughter]

BB: You can’t make it up.

JB: I can’t make it up. So I’m thrilled. And also, one of the friends who’d also been a Rhodes Scholar with me, she was from Zimbabwe. She and her husband were at Harvard as resident tutors. And so they needed scholarship tutors. And having done a bunch of scholarships, I was like oh, I could probably do that. So thankfully they accepted me as a resident tutor. So I was a resident tutor at Adams House. So I was living in Harvard Square and then going to school at MIT. So I had these two communities. So that was how I entered the Cambridge, Massachusetts experience. And now that I look back on it, I can appreciate and can be very grateful for the amount of privilege it was to be in both spaces, simultaneously. At the time I was like, “Yay, free housing and free toilet paper.” Yo, Harvard’s making these kids soft. What is going on, right? Wow. [laughter] They edited out the free toilet paper from the book. But I think the world should know. I really do. It might have changed since my time. This was in 2013. So things could have changed.

BB: How would you describe where you are, what you do today and how did you get here?

JB: Hmm. So I am a poet of code. I tell stories that make daughters of diasporas dream and sons of privilege pause. I am able to do AI research that shows discrimination in products as a way of actually preventing harmful deployments of AI systems. And the way I got to doing this work that really allows me to embrace the artist within, while also having my research hat was a bit accidentally. When I finally made it to my dream school at the Future Factory, MIT Media Lab. I took a… my first course, one of them was science fabrication. You read science fiction, you try to build something you might otherwise not do, as long as you can do it in six weeks. So I wanted to shape-shift, but the six week part made it a little bit challenging. So I was like all right, not going to be able to change the laws of physics, but maybe I could change my reflection in a mirror.

JB: And so I learned about this special kind of material called half-silvered glass. And when you put a black background behind it, it reflects just like a regular mirror, but if you shine light through, the light will go. And so I was like oh, if I put something completely black and then have a mask on it, it can look like a filter. But instead of a filter on a camera like you would have with Snapchat where you have the dog ears, I could actually make that effect on the mirror because of the material.

BB: Wow.

JB: So when I figured that out, I was like, “Oh, that’s how I can shape-shift in less than six weeks.” So I started experimenting with that and I got it to work. And then I thought, okay, right now it’s like a fun… It’s kind of like when you go to an amusement park and they have the cutout and you have to put your face in the right place.

BB: Oh yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah.

JB: Right. So that’s fun. But I was like, “Ooh, what if it could actually follow my face in the mirror?” So that’s when I thought, “Oh, well, we have technology that can actually detect faces and track faces, so let me add some of that kind of technology into my project.” So I went and I found this kind of software that’s meant to do it, and I integrated it into the project I was doing. I know how to program. So I was getting the right code into my project, and then I was excited. I wanted to try it, but it wasn’t actually following my face. So the cool effect I wanted to have wasn’t happening. And so scientists, I start to debug. So I was like all right, let me see if it can get any face. So I held up my hand and I drew like basically a smiley face, right? Two eyes, a nose and a mouth. Held it…

BB: Just on the palm of your hand.

JB: On the palm of my hand. I held that to the camera and it detected not my dark skinned face, but the face I had drawn on my palm. So after that I was like, “Yo, anything’s up for grabs.” So I look around my office and I happen to have a white mask because it was Halloween time and a friend had wanted to do a girls’ night out. So for the girls’ night out, they said bring masks. They actually meant beauty mask. And she had a bunch of Korean beauty masks. So I didn’t need the mask anyways. [laughter] But because of that, that’s why I had a mask in my office. So thank you, Cindy, right? So I have the mask, I put the… Actually before I even got the white mask all the way over my face, it was already being detected.

JB: So it was that moment of putting on a white mask over my dark skin face to have it detected by a machine that I was like, “Oh my goodness, what’s going on here?” So that’s what led me to start asking questions like, How do machines see us in the first place? How are we even training machines to detect people? And also are AI systems as neutral as I assumed they would be because it’s math after all. So that’s what really got me started down this long rabbit hole art project, trying to see if I could shape-shift, seeing that the face tracking software wasn’t detecting me until I put on a white mask. And then really thinking about, oh, my goodness, what does this mean? Maybe this is what I should research during my master’s time at MIT. And so that’s what I did. So I had that white mask experience and I shared it in a TED Talk, TEDx Talk, and it got a lot of views.

BB: Yeah, it did.

JB: So I thought, you know what? People might question my claims. Let me check myself. So I took my TED profile image and I ran that headshot through online AI demos from a number of different tech companies. And some didn’t detect my face at all, just kind of like the coding in the white mask and the other ones that detected my face labeled me male. I was like, “Wait, phenomenal woman here. What’s happening? Why am I being labeled a male?” And so that’s what actually led me to focus my research on gender classification. How are machines even reading gender in the first place? And does it matter the skin type of the person behind the photo? So those were the types of explorations that led to my research. And so long story short, with my research, I tested AI systems from giants we know, right?

JB: So IBM, Microsoft, later on Amazon. And for commercially sold products that they had, AI powered products, they were getting it wrong when it came to facial analysis, guessing the gender of a face. And so they would overall work better on male labeled faces than female labeled faces. They would overall work better on lighter skinned faces than darker skinned faces. And then when you did a deeper analysis and looked at it by skin type and gender, on some of them, there would be flawless performance. Like Microsoft was 100% accurate on lighter males, whereas they were closer to 80% on darker females. And those were the good numbers, right? So then when we go to other companies and we pull it apart, I saw that in some cases the accuracy was around 68% for women with darker skin. And mind you, at this point, we’ve broken gender into a binary, just for the study. So you had a 50/50 shot of just guessing it, right?

BB: [laughter] The toss of a coin.

JB: Exactly. And if we broke it down even further by specific skin type, for type six skin, right? It was close to coin toss in terms of the accuracy. So I was actually curious. I was like, “hmm, I wonder if the companies know.” [laughter] So I sent them the results. Once the paper had been officially accepted to conference, then I shared pre-results with all of the companies, and I shared all of the results, but I blacked out their competitors’ names.

BB: Oh, interesting.

JB: Right? And so I had different responses from the various companies over the two studies that we did. So one response was no response, another kind of…

BB: Which is a response.

JB: Yes. And then the other, IBM was actually proactive. They said, “Oh, come to our office, show us what’s happening.” And part of that is because I had been at this Aspen Institute event and the head of AI research was there. And so the day I was turning in my MIT masters, I was walking from Harvard Square over to MIT and he was there with his two daughters, and he introduced me to his daughters and I said, “Oh, there are findings in here, you’re going to want to know.” And so he kind of already knew that this work was going on, and I had met him. So I think that was part of why IBM was a bit more responsive. And they’ve played this game a lot longer than let’s say Amazon.

BB: For sure.

JB: Amazon was combative, to say the least. So they actually had a corporate vice president attempt to discredit the research. And it got so bad. We had a whole petition was put together by over I think 70 researchers, including the former principal AI researcher of Amazon, saying that if you’re attacking this research, it’s actually going to impede important work in the field of AI because we have to know our limitations in order to reach our aspirations.

BB: Ooh. When I watch the “Gender Shades” and we’ll link to this, if you’re listening, you’re going to want to see this. It’s just… I mean, the way you made it so accessible for me to understand. Now, I will say there’s a part after “Gender Shades” that follows the colon as all good academics have a snappy title, followed by a really shitty serious subtitle. That’s our training. Right? So the full thing is “Gender Shades,” which I love. But what comes after that in the actual title?

JB: “Intersectional Analysis of Commercial Gender Classifiers.” [laughter]

BB: Hey, if she can do that kind of pushup, she can call anything she wants. [laughter]

JB: It was actually funny because I went back and forth with my committee about the title. So that was my compromise. I just wanted it to be “Gender Shades.” Like for the book, I went back and forth with the publishers. I just wanted it to be Unmasking AI. They’re like that’s not how it’s done.

BB: We are a simple title in a complex subtitle world. I never want a subtitle either, but they’re not having it.

JB: Exactly. So that was our compromise. And they’re like are you sure “Gender Shades?” I was like I’m positive “Gender Shades.”

BB: It’s so good.

JB: This is what people can remember. The subtitle, no one’s going to remember that. So anyways.

BB: When I started my shame research, I was just like, can I just call it “Not Good Enough?” And they’re like we need a subtitle. And I was like, “Variables Mitigating Self-Conscious Affect.” They’re like, now you’re talking. And I’m like, “No. Now I’m losing 90% of the people who related to that feeling of not being good enough. So damn it.”

JB: Exactly. But now you get to write books the way you want. So there you go.

BB: I actually, I get to it a little bit sometimes. Let me ask you this. I don’t know if you know S.Craig Watkins, who works at UT on AI, but also has spent some time at MIT and we had him on, and he’s been in AI for 20 years. And one of the things that he talked about that I learned, and I’m curious on your thoughts about this too, as you tell us about what surprised you the most is he just said the idea that when we’re creating AI and building algorithms, that we can only have computer scientists and computational mathematicians at the table and not humanists, and people with lived experiences and liberal arts people and ethicists, he’s like that’s got to end now. And so tell me, one, what surprised you the most and do you agree about building longer, wider tables when we’re developing AI?

JB: Yes. I think what surprised me the most also answers that question. So for a really long time, I felt that to be taken seriously as a computer scientist, I had to hide the art part of myself. And so I struggled for a really long time to embody this notion of being a poet of code. So by the time I was doing my PhD, I asked myself, what would a poetic PhD look like? And I wasn’t sure if I was willing to take that risk, but because I had done other academic degrees, I knew I could go through that process, right? So it was saying, how can I push myself further this time around? And when it came to the “Gender Shades” paper, which we’ve talked about that research showing gender bias, showing skin type bias, and all of these major tech companies with lots of money and resources, I was struck by the fact that all of the companies failed so miserably on women like me, women with dark skin.

JB: And so I wanted to take a look into that part a bit more. And this is what allowed me to start exploring using poetry as a way of sharing what was going on with AI systems. And so after “Gender Shades” came, this poem that I now called “AI, Ain’t I A Woman,” inspired by Sojourner Truth’s 19th century speech in Akron, Ohio, really talking about for the need for women’s rights to be intersectional and think through the lived experiences of other women, not just those who had the podium or the platform at the time. And so I remember waking up with these words in my head. “My heart smiles as I bask in their legacies

Knowing their lives have altered many destinies.

In her eyes I see my mother’s poise

In her face, I glimpse my auntie’s grace

In this case of déjà vu

A 19th century question comes into view in a time when Sojourner Truth asked,

“Ain’t I A Woman?”

JB: Today we pose this question to new powers

Making bets on artificial intelligence, hope towers

The Amazonians peek through

Windows blocking Deep Blues

As faces increment scars

Old burns, new urns

Collecting data chronicling our past

Often forgetting to deal with

Gender, race, and class, again, I ask,

“Ain’t I A Woman?”

Face by face the answers seem uncertain.

Young and old, proud icons are dismissed.

Can machines ever see my queens as I view them?

Can machines ever see our grandmothers as we knew them?”

And then as this was coming, I also started testing images of iconic women, historic women, women from contemporary times. So

“Ida B. Wells, data science pioneer

Hanging facts, stacking stats on the lynching of humanity

Teaching truths hidden in data

Each entry and omission, a person worthy of respect

Shirley Chisholm unbought and unbossed

The first Black congresswoman

But not the first to be misunderstood by machines

Well-versed in data driven mistakes.

JB: Michelle Obama, unabashed and unafraid

To wear her crown of history

Yet her crown seems a mystery

To systems unsure of her hair

A wig, a bouffant, a toupee?

May be not.

Are there no words for our braids and our locks?

Does sunny skin and relaxed hair

Make Oprah the First Lady?

Even for her face well-known

Some algorithms fault her

Echoing sentiments that strong women are men

We laugh, celebrating the successes

Of our sisters with Serena smiles

No label is worthy of our beauty.”

JB: And so that was really my first way of saying, okay, let me let the artist take the stage. And in letting the artist take the stage, those words are also accompanied by visuals. So when I’m talking about Serena smiles, you see IBM labeling the GOAT and her sister, Venus, right? As men. When I’m talking about Ida B. Wells, data science pioneer, you see Microsoft describing her as a small boy wearing a hat, right? And so you’re seeing these images.

JB: So for me, these started to become counter demos or counter narratives to that master narrative of the superiority of tech and tech companies. And it was this way that I realized I could allow people to bear witness to AI failures. So instead of the typical tech demo, which is about, oh, look at all of the things it can do, this kind of demo, which I then ended up calling an evocative audit which was part of what my PhD became.

BB: Wow.

JB: Was to say, how do we actually allow people to see what’s at stake when you have a study like “Gender Shade?” So I wanted to go from performance metrics to performance arts, because that’s when I knew it would actually touch people so they could see what it means when I’m asking, “Can machines ever see my queens as I view them? Can machines ever see our grandmothers as we knew them?” So to that question of who is and who isn’t at the table and who’s bringing their experiences or not, what I learned was the scholarship that came before me was from black women who were bringing in their lived experience. One was Dr. Latanya Sweeney. She was one of my PhD committee members, and actually the first woman to get a computer science PhD from MIT. And some of the work she did, it came through accidentally, almost like my white mask experience. She was being interviewed by a reporter and she was trying to look up one of her papers.

JB: So she searched it and I want to say it was Google and what came up wasn’t just her search for the paper, but also advertisements indicating she might have been arrested. And so the reporter was saying, “Wait, wait, wait. Hold on, hold on. Your paper was interesting, but what about the supposed arrest record?” And she was saying, “Wait, what? I’ve never been arrested, so what’s going on here?” And then the reporter was saying, “It’s because you have one of those Black sounding names, Latanya.” And she’s like, “Look, I’m a computer scientist. This seems farfetched.” So she set up this experiment trying to prove this guy wrong, where she had a list of names that were more likely to be assigned to Black babies than to white babies. And they did the comparison. And in fact, it was the case, right? That the search engine with the ads that would come up would more likely put up a false arrest record for people with Black sounding names.

JB: And that work came before my work. But that was showing bias in search engines. And then I was looking at the work of Safiya Noble, also great researcher, Dr. Noble author of Algorithms of Oppression, MacArthur Genius Award winner, so much respect for her work and her work she was looking for activities for her daughter to do. I think there was a sleepover happening. Kids were around middle school. So she searched Black girls. What she pulled up instead of activities for Black girls were pornographic images more often than not. Similar thing if you put in Asian girls. White girls, a little more innocent content. And so that also sent her down this exploration that then led to the book Algorithms of Oppression, the MacArthur Fellowship and all of that. And so I say this to really point to the legacy of Black women in the tech space, right?

JB: Who have used their own lived experience combined with their academic training, combined with their technical expertise to open up new schools of a scholarship. And so in my PhD, I make this argument about the importance of Black feminist thought and then ethics of care and going beyond positivism. When it comes to the way in which we do research and saying lived experience truly matters. And then I map it with the research that they did. And then how my personal experience of coding in the white mask builds on that. Then I go back to Sojourner Truth, and I go back to Frederick Douglass and I show how they were using daguerreotypes and the imaging, the advanced technology of their era. So now how we have AI, oh everyone’s excited; there to have a photo of somebody was incredible. But those kinds of images were being used to support a scientific racism to say, “Look at the shape of this head. Clearly an inferior specimen of a human,” this sort of thing.

JB: And so they actually took that same technology and they had dignified portraits of themselves. So in “AI, Ain’t I A Woman,” I intentionally use one of Sojourner Truth’s images taken like that. She said, “the shadow supports the substance,” because she would sell these images. And that’s the image that I show Google labeling her as a clean shaven old gentleman. So there are all of these historic connections. And so as somebody who’s a researcher and an artist, I do oftentimes, and I did especially earlier in my career, feel like I wouldn’t be respected as much, if I talked about my lived experience or if I let the art aspect come through, it would be viewed as too subjective and thus disqualify the data that I had gathered. And so in conceptualizing this notion of the evocative Audit, this was actually saying, no, this is also a valid form of knowledge. And in fact, it builds on Black feminist epistemology, you know? And so this is all within my MIT PhD alongside the algorithmic audits of Amazon and others. So I was saying, you can put the algorithmic audit with the evocative Audit, and you can actually reach more people that way.

BB: When you were reciting your poetry, I didn’t understand the bias. I felt the bias. It takes me on a trail from Frederick Douglass to someone we both know, Sarah Lewis at Harvard to the power of art and imagery aesthetic force.

JB: Absolutely.

BB: And when you think of the evocative Audit, I’ve mentored so many female PhD students, Latina, Black, white and the compelling need to orphan the art in themselves to be seen, to feel like a place is earned at the table when that is their power. Do you think that’s changed at all, Dr. Joy? I mean, do you think… Or do you think there’s a season for it in a career? Like what do you make of that? Because I still see it with the PhD students.

JB: I think for me, there’s a reason I started with the tech, right? So by the time I’m doing “AI, Ain’t I A Woman,” I have three degrees, technical degrees, learning and technology. Like in some ways, I felt that I had “paying my dues”. And I think that’s not necessarily a good thing. That was the armor I felt I needed to have to let the turtle artists come out. And what I found so fascinating with “AI, Ain’t I A Woman” was how far it traveled. I think I was most surprised at some point I had through one of my mentors recommended to be on the EU Global Tech Panel. So president of Microsoft others. And I remember being in Belgium and showing “AI, Ain’t I A Woman” for the first time on this EU Global Tech Panel. And just the response to it because it’s so visceral, and the only other dark faces in that room were just the faces in the video and mine.

JB: And even before showing it, I almost didn’t make it into that room because the human gate checkers were asking me, what business did I have at this high level convening. And I mean, I’m five feet two inches, I barely looked 28 at the time, you know? And so it was the thinking about how the physical gatekeepers become algorithmic gatekeepers. And then looking at who has, again, a seat at the table. So the head of the World Economic Forum was there and he saw it. And then later I was invited to Davos. And so I presented “AI, Ain’t I A Woman” in that space. And later it was shown to EU defense ministers ahead of a conversation on lethal autonomous weapons. And again, this is what I mean by how far it could travel. Because at the end of the day, the storytelling connects all of us.

JB: And that’s what the poetry is doing. That’s what the evocative audit is doing alongside these photos, you cannot unsee. These are the biggest, most powerful tech companies, right? And here are iconic faces of women that I respect so much. And if you’re getting Oprah’s face, when I showed Amazon misgendering Oprah. It’s not like she doesn’t have photos available. So the other thing I found with the evocative audit was being able to show and not just tell, helped us get to the conversation. So, instead of like oh, I’m not sure if this is really a problem or this, that, or the other, it’s almost the mic drop; white Mask, mic drop “Ain’t I A Woman?”, mic drop.

BB: Mic drop.

JB: “Gender Shades.” Okay, let’s get to the conversation. This is real, this exists. You’re not going to gaslight me into saying it’s not a thing. But also more importantly, it invited other people into the conversation. So I spent so much time trying to make the “Gender Shades” results as accessible as possible. So taking the time to do the video, the interactive website. So later on and you see this in the film, the documentary Coded Bias, when I go to the Brooklyn tenants and I’m working with people there, mainly women of color who’ve had the landlord install a facial recognition entry system. And so they’re saying it feels like Fort Knox just to get into their house. They were saying, “Thank you for the website,” because it made the information so clear where you don’t need to have a PhD from MIT to know that this is wrong.

JB: Right? And so that was a thing that I kept struggling with, even when I was thinking about, do I really want to finish the PhD and so forth, the work that I was doing, what I delivered as a poet, that was already there without the MIT degree. And so it’s not what enabled the poetry, but I was also very aware of the use of institutional power and the use of narrative power. And so I write all of this in my PhD, the ways in which I’m using credentials for institutional power to get into the halls of Congress, to get into EU Global Tech Panel, Davos, other spaces. But alongside that, I’m bringing the narrative power to say, these are the marginalized, these are the X-coded, and they matter, and they must be centered in these conversations.

[music]

BB: I just can’t aptly tell you how grateful I am for your work and your ability to not just do the work, but name the process of how the work is coming to you, and getting to me. I know quantitative… like what I would call, not nicely, but hardcore quantoids would claim you as their own. But I’m like, no, she’s one of us. She’s a qualitative person. She’s an ethnographer qualitative person for sure. And then I was talking to a friend and she’s like Dr. Joy, she’s quantitative to the bone. And what I think is so interesting is that the answer is, yes. You are both qualitative and quantitative. You are institutional and narrative. You are poetry and code.

JB: Daughter of art and science.

BB: A daughter of art and science. And a pole vaulter.

JB: Only to show I’m stronger.

BB: I mean, but I think your pole vaulting is not just physical pole vaulting. I think you take a really hard, fast run at things and fly right over them and bring us along. I could work the pole vaulting metaphor for your work until you were in tears and begging me to stop.

JB: I mean, I tried, in the book, I talked about the difference between bar-gazing and star-gazing, and then I did snowboarding. The athlete in me said, “Just a little bit here. Just a little bit.” [laughter]

BB: I picked up, I picked it up, I picked up the crumbs you were laying down as an athlete. Yeah. I get it.

JB: I try to leave something in there for everybody. For sure.

BB: Let me ask you this. How do you envision the future of AI in our daily lives with respect to human dignity and freedom?

JB: I have a poem about this. If you permit me to share it.

BB: Oh my God, yes. I would love it. It would mean everything. Yes.

JB: Okay. So it’s in the section about the Brooklyn tenants. Let me see. So intrepid poet. I think it’s safe now that I have all this academic tech cred armor for cover.

BB: You’re in the door.

JB: So I’m like, all right, let’s do a little poetry.

BB: You are the door.

JB: So then I had the opportunity to work with the Brooklyn tenants. And it was at a time during my research where after research had been attacked. And I felt that the people who were closest to me academically didn’t stand up for the research in the way I had hoped at that time. I was just like, is this really where I want to be? And when I got the opportunity to work with the Brooklyn tenants who were resisting the installation of a facial recognition entry system as the way to access their homes, I was so inspired by them.

JB: And I was like oh, I’m not doing this for my committee or for my supervisor or for the institution. I’m doing it for the X-coded, I’m doing it for people like the Brooklyn tenants. And so this is the poem I wrote for them. “To the Brooklyn tenants resisting and revealing the lie that we must accept the surrender of our faces, the harvesting of our data, the plunder of our traces. We celebrate your courage. No silence, no consent. You show the path to algorithmic justice requires a league, a sisterhood, a neighborhood, hallway gathering sharpies and posters, coalitions, petitions, testimonies, letters, research and podcast, dancing and music. Everyone playing a role to orchestrate change. To the Brooklyn tenants and freedom fighters around the world, persisting and prevailing against Algorithms of Oppression, Automating Inequalitythrough Weapons of Math Destruction. We stand with you in gratitude, you demonstrate the people have a voice and a choice. When defiant melodies harmonize to elevate human life, dignity and rights, the victory is ours.”

BB: God. Oh God, it’s so good.

JB: And that’s truly how I felt when I saw, oh my goodness, these aren’t people with PhDs from MITs. These are people who saw a problem, educated themselves about it, reached out and resisted, and resisted successfully. And for me, that was such an inspiring model to understand that the research I was doing could equip people on the front lines. And that also people seeing themselves identified in me in various ways. People know whether you’re the outsider because you’re a woman or you’re an immigrant or you’re more of the artsy person in a very technical field, whatever it might be. And seeing that inspiring others that gave me the motivation I needed to continue.

BB: Weapons of Math Destruction.

JB: Yes. Book by Cathy O’Neil. So that whole part is a bibliography. Can I nerd out a little bit?

BB: Yes. I mean, yes. I know. Go. Go. Go.

JB: Okay. Algorithms of Oppression, I already mentioned Dr. Safiya Noble, Algorithms of Inequality. Right? Automating Inequality. That’s a book by Virginia Eubanks, through Weapons of Math Destruction, that’s book by Dr. Cathy O’Neil. So that whole thing is a bibliography.

BB: Yeah. I mean, it is literally a bibliography. It is literally a shout out.

JB: Yes. For those who know, you know. So all these gems dropped out throughout for sure. And then also going back to Weapons of Math Destruction, when I was… I wasn’t sure I wanted to do this research in the first place. Because, calling out big tech could be dangerous, right?

BB: Yeah.

JB: I was on the fence. And I had a mentor of mine tell me that Cathy O’Neil was coming to do a book talk, and she was doing a book talk literally on the same block I live on. So I went to that book talk, it was at Harvard Bookstore, and I saw this blue-haired, blue-eyed mathematician, talking about how machines can be harmful and problematic. And until then I felt I was a little alone in these observations. And so I remember introducing myself and telling her about computer vision.

JB: She was kind of following what I was saying, but for me, I was like, oh, I’m not alone. If I’m going to be a gadfly, I might have a Ella. I was like, okay, all right. We can do this. Weapons of Math Destruction was a really inspirational book for me. And now, Cathy O’Neil, later in the book, I talk about how we team up to do an algorithmic audit for Olay. She knows nothing about skincare. As an Olay Ambassador, however, I am now better versed on skincare. That super serum is great, clinically prove it, you know.

JB: But we had so much fun together. And then, we’re both musicians. Cathy’s an amazing musician. She plays all the things, but she also plays fiddle. So from time to time I’ll go. Her mom’s also an amazing mathematician, so she’ll invite me over. Her mom will be solving the hardest math puzzles you’ve ever seen, correcting Cathy on the solution. I’m like, I just love this love, I love everything about this. And then she wrote this data science book from way back in the day, O’Neil and O’Neil, because both of her parents were mathematicians. And then she was a computer scientist and she’s, I guess they call us data scientists now. She’s just the best. So you have these incredibly brilliant women we’re spending, I have the opportunity to spend time with them, eat with them, chill with her sons, and then we make music together. So that’s from that first time of seeing her at a Harvard bookstore, being so inspired to now being able to call her a friend and drop her references in some of my poetry.

BB: It’s beautiful. It’s just, it’s beautiful. You must be in the minds of big tech, the scariest poet on the planet.

JB: I’m just a poet. What could a poet do?

BB: Oh, really? Do we want to get into the wars, the heartbreak, the murders caused by poets throughout time. I mean, I never underestimate the power of a poet. Come on.

JB: No. That’s why they burn us.

BB: Okay. I have one question before we get to our rapid fire. I get a lot of texts and emails from friends of mine who are writers, fiction and nonfiction, that our books have been fed into the machines. I don’t know exactly how that works, but I know my books have been fed. We just kind of kick back and that’s good? Or what is our thinking about that? It doesn’t feel good, but I don’t know. I’m asking for both the mathematician, entrepreneur and poet in you to braid an answer together. That’s heart commerce and IP protection. And let me know what you think.

JB: Sure. As a new member of the Author’s Guild and also the National Association for Voice Actors, this topic came close, very close to home once I became a published author. And I started looking at the ways in which the work of so many authors had been used to train generative AI systems. And this is why I call them regurgitative AI systems. Because oftentimes the best of what we see in AI that’s impressive, is because it’s been fine tuned on some of the best of what’s been made by human creators. Be they visual artists, authors, filmmakers and so forth. And so for me, we are really looking at what you could view as a heist. You didn’t know.

BB: No.

JB: That your books were included in data sets used to train powerful generative AI systems. And you don’t need to have any kind of tech background to know it’s not fair for companies to get billions of dollars of investment to then sell products that are made using your work and argue fair use when it’s copyrighted. And also when some of those outputs can almost be whole entire paragraphs or samplings of that work. And furthermore, now you have the ability for some of these systems to say, write this in the style of, let’s say let’s make it a Brown style. Or let’s make it a Buolamwini style. Or let’s do it in the style of an artist. And so you’re seeing right now, lawsuit after lawsuit, right? Because of the ways in which AI systems that are called generative are truly regurgitative systems. And they’re regurgitating the hard work and the IP of artists from all around the world. And we also have evidence of this. And so the books, data sets that have been used to train some of these systems, we have the titles, we have the authors. So we can say, “Yes, actually this author’s work was used to train this particular system and no, it’s not fair.”

JB: And so this is part of why we launched this campaign with the Algorithmic Justice League. So that’s my day job. I like poetry, I like writing and things like that. I’m also the president and artist in chief of the Algorithmic Justice League. And we really fight for the X-coded people who have been excluded or exploited, by AI systems or AI companies. And in this case, when we’re looking at the future of the creative class, we have to push back and demand creative rights. And so what do creative rights look like? Well, first of all, consent. Hello. Ask, right?

BB: Yeah. Basic.

JB: Basics. We are talking basic. So it shouldn’t be, after the fact that you find out, oh, my book was used to train or my books in your case was used to train these systems. Compensation. And so it’s not just acknowledging that the books were there, it’s making sure that there is fair and adequate compensation for those whose work has been used in this way. I think that would be a form of redress. And then there’s also this notion of control. And this part I find really fascinating because this is what I was grappling with when I recorded the audio book for Unmasking AI. I’m busy. You are busy. They said it would be four days in the studio. Actually the same studio I’m in. I was like, maybe this is an opportunity for AI voice code, right?

BB: Yeah.

JB: And I thought that might be an option because I didn’t understand that voice acting is an art.

BB: Oh. God it’s hard.

JB: And it wasn’t until I was working with the director who’s won the Oscar version for voice acting and all of that. That she really helped me appreciate it. I thought I was going to be reading aloud. No, I was performing. And by the time I would get home every day at around 5:00, I was out by 6:00, I was done. And it was that process that just made me see how easy it is to underestimate the art forms that you don’t call your own.

BB: Oh my God. Yeah. I mean, do you know that I can only do three and a half to four hours a day of that? It is so difficult to do that well.

JB: Absolutely. And then also the voice can only go so far. I made the mistake of having, I think I don’t… I had [unintelligible] because of that. My voice was cracking. So I was also learning different things just about being a biological being that made it… I also had an attitude, you know.

BB: [laughter] No?

JB: I had an attitude. So there would be some parts of the book where I’m talking about insults. I think I was reading through the TED insults. So I was struggling each time I was reading it. And director was so patient with me. She is like, “can you…” “I’m going to repeat it. Just give me a second.”

BB: Oh wait, no, I wish I would’ve been in the recording thing next to you. Because we could have had, yeah. Because I mean, I literally would start talking and then they’d be like, you have to do that again. I’m like, “Mf’er, that’s the hardest story of my adult life. I am not saying that again.” And they’re like, “No, you have got to go again.” I’m like, mother trucker.

JB: Right. Or you’d get close, but you’d like transpose one word. No. I also learned, I can’t correctly pronounce many things. But I will do the English as a second language card.

BB: Okay, Oxford. Oxford times two.

JB: Out of excuses here. No, but that was a whole fascinating experiment for me. I actually wrote this whole op-ed. It’s not yet published, but it was just about how easy it is to underestimate the art forms that aren’t your own.

BB: That’s it.

JB: And so the control piece, if I have… Now that I know voice acting is a lot more than I thought it was, I would never actually want to use an AI voice clone for that type of work. But there might be other type of work where you decide, you have the agency to say, Hey.

BB: That’s it.

JB: I want to experiment with AI in this way. Or maybe I’m using AI to do a thematic analysis of everything I’ve written on this particular topic. And so using it as a tool to boost collaboration or something in that nature, you should have the control to do that. So that’s that third C and that fourth C is credit. Again, this is why I keep calling it regurgitative AI. Let’s credit the artists who make what seems breathtaking from AI possible.

BB: I’m just writing down these C’s because they’re very important to me.

JB: Yeah. Ajl.org/writers. You’ll see the four C’s there. We have the four C campaign. So ajl.org slash writers.

BB: I’ll put that up y’all on brenebrown.com so you can find it. But I think consent, compensation, control and credit is the entire way I’ve been brought up about work, period. As an academic. This is really important work. We’ll link everything to it. I’m going to sign up or whatever you do over there, because I support this movement. It’s so easy to underestimate the amount of work and art that you don’t create. And that’s like when you’re walking through like the Louvre and people ahead of you are like, “Oh, I could have done that.” I’m like, “Dude, then where’s your… show me your art. I’d like to see it too.”

JB: You can regurgitate it when you hear the line, when you see the final creation. But you cannot reproduce the process of creation as it went through the lived experience of the artist who gifted you that work.

BB: And there we end and we go right into rapid fire because that was beautiful. Okay. Are you ready?

JB: Ready.

BB: Fill in the blank for me. Vulnerability is?

JB: Unmasking truth.

BB: I can’t cry after each of these. Get your shit together, Brené. Okay. One piece of leadership advice that you’ve been given that it’s so great, you need to tell us about it or so shitty, you need to warn us.

JB: This one is probably on the warning side. I was in an executive education course and one of the professors described leadership as the distribution of loss at a pace which people can handle.

BB: Oh my God.

JB: And I could see the perspective coming into a new organization as an outsider trying to bring in change. So they were talking about how often it happens when somebody is brought in and they try to change things too quickly without really understanding the stakeholders or the motivations or what people will perceive as loss with that new thing they’re bringing. So I got it from that standpoint, but it didn’t sit well with me from… I’m a storyteller, right?

BB: Yeah.

JB: So like, ooh, do we start with disincentives or do we paint a compelling vision? So that one I still… I find it useful in that it’s thought provoking. Okay. What’s driving that particular perspective?

BB: Yes.

JB: And in which context does it make sense? And then I also found that it reaffirmed my approach, which is more joyful, as you might imagine.

BB: Yeah. You’ll appreciate this. One of my favorite leadership quotes, and I think you’ll appreciate it. Because it’s the paradoxical piece. It’s from John March who was at Stanford, and he said, “Leadership is poetry and plumbing. You have to be able to cast a vision that inspires and build systems that deliver.” Isn’t that good?

JB: Poetry and plumbing. I like it.

BB: I kind of like it. Yeah.

JB: Yeah. I’m going to have to write that one down.

BB: We’ll send it to you.

JB: Thank you.

BB: Okay. You ready? You, Dr. Joy, are called to be very brave, but your fear is real. You can feel it in the back of your throat. You can taste the fear. What’s the very first thing you do?

JB: I pray. I pray.

BB: Last TV show that you binged and loved.

JB: Ooh, Bridgerton. And also I got to meet Adjoa, who is… I was at the NAACP Awards. I was there for my situation and people were like, Dr. Joy and I was like, look, this is my fan girl moment. I got to go. I got to go meet some queens over here. And so season three is coming out, but they were there for Queen Charlotte. Oh my gosh. So I binged Bridgerton. Then of course I had to watch all of Queen Charlotte as well. So yeah, definitely excited for the new season to come out. I also watch a bunch of nature shows, but I don’t binge them the way that Bridgerton I have got to know what’s next.

BB: Queen Charlotte.

JB: Also really interesting with Bridgerton. When Gemini came out with, Google’s Gemini AI prompt system, so text to image, I was describing it like Bridgerton, because you would put in something like the founding fathers and they were showing Black men as founding fathers in the US to which there was a public outcry. This is not an accurate representation. And that they put in Pope. And there was a Native American woman as Pope, what is going on with this kind of representation? I was like, okay. So this is almost Hamilton Bridgerton.

BB: I mean, Shonda Rhimes got a hold of Gemini.

JB: In that way. But what I found fascinating was people who were used to being centered were marginalized. And so the experience of this kind of reverse symbolic annihilation, and then also how quickly Google shut it down.

BB: Oh, did they?

JB: But those were… They did, they took it offline. And people were calling it Woke AI. These were actually evocative audits. These were examples of real world evocative audits. But when I started reading and seeing the examples or for example, they did, Nazis, who were, I think… I don’t know if they had them as Asians in their representation. I’ll need to double check. Okay. So these were not historically accurate. So it led to another kind of conversation about representation. Particularly when you’re talking about the past. And then it made me think, because so often AI is described as being a mirror. Like, okay, it’s bias, but we’re also biased. But oftentimes what I see is AI is a kaleidoscope of distortion. And that’s a bit of what we are seeing with Gemini as well. But I go on and on.

BB: I love it.

JB: About these things.

BB: Okay. So I might have to send you a DM when we’re in the middle of the new Bridgerton series. Because I’m into it.

JB: Yes.

BB: I’m such a fan. Okay. Favorite movie.

JB: Favorite? Ooh, this one is hard. I’ll say The Sound of Music, because that’s partially how I learned English. I would watch it almost every day when I was four and it was my on-ramp to the English language. So Sound of Music and my brother would come home. Sound of Music again.

BB: I do love The Sound of Music. A concert that you’ll never forget.

JB: Ooh, I recently went to an Iniko concert. She does this song called “Jericho,” which has become kind of my theme song. Because she has this part… “I’m your future, past and present. I’m a fine line. I’m the missing link of this illusion.” But she’s talking about artificial intelligence in many different sorts of ways. It’s just an incredible ethereal sounding song. And I first heard it acapella, it was this TikTok viral sensation. And then I heard the full piece and I thought, oh my goodness, this is literally the theme song for Unmasking AI. So when she came to Cambridge, I got the meet and greet. I signed a book for her just to let her know how excited I was about the kind of music she’s making. So that was an amazing concert to attend and then to share that experience with friends as well. So at The Sinclair.

BB: I love that. And we’ll link to the song. Favorite meal?

JB: Favorite meal? Ooh, wow. I just went to Ghana for the first time in 30 years, and I was well fed by so many different family members. But my mother’s older sister, she makes stews just the way my mom makes stews. And I hadn’t tasted her cooking since I was maybe three. And so what I appreciated about that experience was how familiar it was. And then when I was in Ghana, I have so many cousins and so many people who look like me and my brother. And we’re just, because growing up in the US we were the four of us, our little unit. And I would always kind of feel a bit of a distance when people would talk about all their cousins. I was like, oh, I wish I had cousins close by. Or aunties and uncles and I do. And they’re there. So we had an amazing, time together. But meals just, or sitting next to my grandmother. Okay. So when my grandmother and I did the thing where you hold the Unmasking AI book, her facial features match this so perfectly. It’s uncanny. I was like, “Oh my goodness.” And also the way her hands were, you could, so her hands were like.

BB: On the mask? Yeah.

JB: It was like, so it was this, her hands were there and then it’s her face and it’s this perfect match of the face on the book. And I’m thinking, wow.

BB: That’s powerful.

JB: The legacy is there. Yes. So favorite meal.

BB: Then eating stew that tastes like home, I mean.

JB: Yes.

BB: What is a snapshot of an ordinary moment in your life that gives you real joy?

JB: Probably sitting on my couch, playing my guitar, making up some song. I love words and playing around. So making up some random song about something that’s happened. Yeah..

BB: Beautiful.

JB: Pull it out.

BB: And then one thing, last question. One thing you’re deeply grateful for right now in your life.

JB: I am so deeply grateful for my grandmother. Again, I mentioned this trip that was three decades in the making. And to see the family she’s created. My grandfather actually died before I was born. And I think she lost him when they were both in their 50s. And then to see the legacy of everything that has come through her in her children and in her grandchildren. I’m just so grateful that I was able to see her. Looking forward to seeing her again. I call her Nana. And so I’ve been calling her Nana AI and Nana Romo. So feeling really grateful for my grandmother in particular and for my lovely extended family and also for these genes. Because I met my dad’s sisters who used to look after me when I was little. And I felt like I saw my future. And the future is bright. The future is bright, the skincare is tight. So I was like, okay, life is, I’m grateful for that. Grateful for these genes. Thank you Mom and Dad.

BB: Yeah. They delivered. Unmasking AI is just one of the best books I’ve read. It helped me so much. I felt walked through it by you. I didn’t feel alone when I was reading it. I felt like I had a guide. And I felt not just your mind, but your heart, and that makes a big difference.

JB: I’m so glad to hear that because that was my hope. I wanted people to not feel like, oh, AI tech, this is a topic I can’t engage in. I really believe if you have a face, you have a place in that conversation. And I wanted to be that friend to invite you into the conversation. So your nerd cousin that went to tech school but can still speak to people. I wanted to be that person for others.

BB: You felt like that person in there for me.

JB: Thank you.

BB: I never lost sight of your heart the whole time.

JB: Thank you. Thank you.

BB: Yeah. And I really appreciate you being on the podcast.

JB: Thank you so much for having me here.

[music]

BB: I told y’all, I told y’all that this was going to be an amazing conversation. I learned so much. Not just about technology and AI and racial bias, but about myself and about what it means to engage with your whole brain, your right side, your left side. To be an artist and a coder, to be a poet and a mathematician. Dr. Joy is just a beautiful person doing, I think, lifesaving work given what we’re looking at. This series has been just one of the most interesting and hardest and scariest things that I’ve ever talked about and done. Because I think AI is not coming, it’s here. And the more we know and the more we can talk about it, the more we can make decisions informed by our values and our ethics. You’ll find everything you need to find about Dr. Joy on brenebrown.com, under her podcast, her Instagram, all of her talks. I’m going to do one final episode where I just talk about what I’ve learned and how it’s changed how I work and how I lead our organization. I really appreciate you being with me on this really weird walk through AI, technology, social media, all the things that are living beyond human scale. Y’all stay awkward, brave and kind.

[music]

BB: Dare to Lead is produced by Brené Brown Education and Research Group. Music is by The Suffers. Get new episodes as soon as they’re published by following Dare to Lead on your favorite podcast app. We are part of the Vox Media podcast network. Discover more award-winning shows at podcast.voxmedia.com.

© 2024 Brené Brown Education and Research Group, LLC. All rights reserved.