Brené Brown: Hi everyone, I’m Brené Brown, and this is Unlocking Us. Oh, I have such a special conversation for y’all today. I am talking to my friend, thought leader, culture shifter, change-maker, Austin Channing Brown. She is a leading voice on racial justice and her book, I’m Still Here: Black Dignity in a World Made for Whiteness, has been transformative for me. We’ll talk about this in the conversation, but I often say that I evaluate a book by how many times I threw it across the room while I’m reading it, and this book, let me tell you, has some flight hours under it. God, it’s so beautiful. And clearly, I am not the only one who has found the book transformative. Reese Witherspoon, who has an incredible Hello Sunshine Book Club, just announced that I’m Still Here is one of two books that she’s picked for her June 2020 book club read. Austin is also the co-creator and executive producer of a video web series, like a TV series on the web, called The Next Question, which I’ve had a chance to be a guest on, and it’s… What a conversation.

BB: Laughed, sobbed, just incredible conversation. It’s really, the series is hosted by Austin and also co-host Jenny Booth Potter and Chi Chi Okwu. And it’s a very different kind of conversation. It’s about the expansiveness of racial justice. What does anti-racism really look like? I highly recommend it. And last, but certainly not least, this is really exciting. Today is June 10th, this is the day this podcast is dropping, and Austin and I are partnered in a movement called “Share the Mic” where white women with big social media platforms amplify the voices of black women anti-racism activists. And so today, June 10th, 2020, in case you’re listening, you can go back and find it, Austin will be on my social media and sharing her thoughts, sharing ideas, and then this evening we’ll do an Instagram Live on her Instagram, which is @austinchanning. I just want you to get on my Instagram, which is @brenebrown today, June 10th, I want you to get on Austin’s today and always follow her @austinchanning and then join us for the Instagram Live tonight. Last, just to let you know this bit about Austin, which I think is important because you’ll see that not only will she share her massive knowledge with us, you’ll get to know her as a person, which is a real privilege. Trust me. She lives in Metro Detroit with her husband, her son, and what she would describe as a very spoiled puppy. Okay, let’s get into the conversation with Austin.

[music]

BB: Austin Channing Brown, how are you?

Austin Channing Brown: It’s a weird week.

[laughter]

BB: It’s a weird week, but I want to… I was starting with that question. Really truly, I want to dig into how you are. I was starting with that question around when COVID first started.

AB: Yeah.

BB: And now it just has… The answers are further and further away from fine.

AB: I feel everything right now. I feel really, really sad, I feel overwhelmed, I feel betrayed, but I also feel inspired by the protesters. I feel encouraged by how many people are seeking police reform and even police abolition in some cases. I feel like… It feels like one hot, beautiful, ugly mess. [chuckle] And I feel all of that inside my body right now.

BB: How are you taking care of your body, and your mind, and your spirit right now?

AB: Not doing a great job, and I think that’s because my body is constantly fluctuating. So at the beginning of all of this, I was eating pretty regularly. And the worst things got the harder it became to eat. And sometimes, that’s because of posting in the news and getting lost in social media. But really, Brené, I’ve realized that I don’t have the same appetite. I don’t want to eat. And I feel nauseous a lot, a lot. So it’s been hard. The self-care has been hard when your body isn’t telling you what it usually tells you.

BB: I don’t even know how long ago this… I think it may have been the first therapist I ever saw, so I must have maybe been 20. And I remember her telling me… I was going through a really hard time, and my family was falling apart, and it was just one thing after the next. And I said, “Sometimes I go a week and I just… All I can do is eat. And then other times I can’t even swallow because I feel so nauseous.” [chuckle] If you all can see Austin right now, she is shaking her head yes.

AB: All of that, right? It is… The self-care is really, really hard. So I think just… I’m just trying to be gentle with myself and… The one [chuckle]… I’m almost embarrassed to say this, but it’s the truth, and so, the one thing that I’m doing very regular, very regularly is giving myself a little face mask.

BB: Oh my God, I love it.

AB: I bust out my little jade roller, I stick that baby in the fridge, so that she’s nice and cold. [chuckle] I roll that jade over my face. I have 11 steps. I mean, I am in it, Brené. I’m in it.

[laughter]

AB: When this is all over everything else might be a mess, but my skin will be happy Brené.

BB: It’s going to be glowing.

AB: Yes, I will be moisturized when this is gone.

BB: But you know what, that sense of touch…

AB: Exactly.

BB: And that sense of pleasure and that sense of self-love that goes with that touching and I have one of those rollers too and I’m just like come to mama just yeah, just take it all away.

AB: Yes, yes, yes and I realize that because I’m doing this skincare I’m actually looking at myself in the mirror, I’m looking into my own eyes, I am breathing in the scent of all these products, it really is 10 minutes of pure pleasure and it’s the only thing my body is telling me explicitly saying, do this, do this, I don’t care what time it is, I don’t care if it’s after midnight, I don’t care if the baby is not down yet, I don’t care what’s happening on the news, do this for me and so that is my one little action of self-care that I do almost every night.

BB: I love that, and I love looking into your own eyes. Yeah, I was going to say about the therapist that I thought was interesting, just… I don’t know if this is helpful or not, but it’s been helpful for me for the last 30 years since I heard it. She said often when we’re depressed, we crave and we eat, but when we can’t swallow and we are nauseous and we have no appetite is often a sign of despair, and despair sometimes makes eating and almost just even the act of swallowing hard.

AB: Wow, that resonates so deeply, the despair. That resonates so deeply and the reason it resonates so deeply, Brené, is because I don’t… This is so hard to explain Brené. I know despair is there; because I’m working through the crisis, I don’t feel it.

BB: That’s right, that makes sense.

AB: I feel numb to the despair, right?

BB: Yes, yes.

AB: I am thinking about the next thing, I am thinking about what homework I’m going to give people, I am thinking about how to steward this community through this moment, I’m thinking about what I’ve already written, I’m thinking about how to move us toward black freedom, and so I don’t feel much of anything except nauseous. That makes so much sense to me.

BB: Yeah, it makes so much sense to me. I don’t know, I remember hearing Rob Bell reading something that he wrote that he defined despair as “the fear that tomorrow will be just like today.”

AB: Ohhhh, mm-hmm.

BB: Yeah, and I don’t know, I wonder… I’m thinking just about neurobiology right now as we’re having this conversation, I wonder if you can both… I don’t think it’s humanly possible, I think I’ve seen the data on this actually, to both teach and facilitate and walk us through for change and action around black dignity and let yourself feel the despair that nothing will ever change. Yeah, I just don’t know that we’re built to do both of those things, I don’t think we are actually built to do both of those things at one time.

AB: That feels accurate in my gut. So for example, I have not been able to watch the video of George Floyd’s death, I cannot do it. On the couple of occasions it has come on the television I have either had to turn away or have just turned the TV off all together, I am very aware that my emotional capacity can only handle so much and yet, there haven’t been any tears, I haven’t collapsed on the floor, I haven’t… There hasn’t been any of that but I think you’re right, that the despair is showing up in a way that I can handle and in some ways it’s enabling me to not practice self-care, because if I don’t have to stop to eat because I’m generally not hungry, then I can teach for four, five, six, seven hours a day.

BB: Non-stop.

AB: Yeah.

BB: Yeah, I just… For those of you all listening I know it’s probably clear that we’re friends and we’re not just meeting on this podcast. I guess what I feel right now is that God, I just… My prayer for you and my.. is that I just want you so desperately to take care of all of you because I love you but we also just… We need you and I wonder sometimes I’m thinking right now, especially with the advent of calling in the military on the American citizenry I just wonder exhaustion and wearing people out is such a tool of oppression as well.

AB: Oh, absolutely. We saw it first in Ferguson, those were the most recent reiteration of this and I remember being tired for the protesters because they just kept going night, after night, after night, after night, and now that people are battling health concerns and battling unemployment, battling family dynamics all being cooped up in the house together – people have to be exhausted, everybody is exhausted.

BB: Yeah, everybody is exhausted, everybody… It’s funny too because I think a lot of white folks are feeling a weariness that has been a part of the DNA of black experience since the beginning of the time in this country.

AB: And that’s part of it, right Brené? Is that we’re not new to this.

BB: Right.

[laughter]

BB: Right, right. Yeah.

AB: Our exhaustion isn’t the last week.

BB: Exactly.

AB: Our exhaustion is since we were born. [chuckle] Our exhaustion is… Our exhaustion is our parents’ memories and our grandparents’ memories. This exhaustion is long. It’s long.

BB: Yeah, it’s bone exhaustion… It’s just, yeah, it’s DNA exhaustion.

AB: Yeah.

BB: It’s… You’re born into a history of weariness, I guess. We know oppression weariness it’s…

AB: Right.

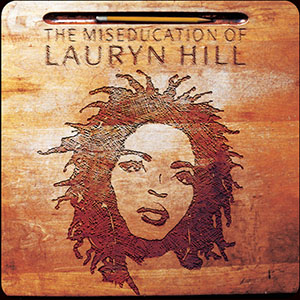

BB: Yeah, it’s real. For those of you who don’t know, Austin has a book called, I’m Still Here: Black Dignity in a World Made for Whiteness. Now, the way I first described… I don’t remember if we talked about this on your TV show or we talked about this another time, but whenever a book… Whenever I have a book that really changes me but kicks my ass first, I always say that book has wings, because I throw… I usually actually throw the book.

[laughter]

BB: And I do, like I’ll just be… I’ll be lying in bed reading and I’ll be like, “Oh, no bullshit,” and I just throw the book and it… And the corners of your book are dinged up. Your book has wings.

[laughter]

AB: I love that. I actually ask people, particularly white people, black women do not want to throw it, but I always ask white people did you throw it after they read it because I expect that though.

BB: Do you really?

AB: Oh, yeah.

BB: No.

AB: And I’m disappointed when they say, no.

BB: Jesus, I’m part of a gang of middle-aged white woman book throwers. Holy shit, deliver me now. Yeah, it’s… The book is so honest and unflinching.

AB: Yes, purposefully.

BB: And as a person of faith.

AB: Right.

BB: I read things that I knew were true and gave me words for confusion about why, in these moments, I don’t understand why this is not the sermon every Sunday.

AB: I lived it first, Brené. I lived it first.

BB: Say more.

AB: So I feel like I’ve kind of lived dual lives in terms of faith. My faith was born in a black church. But growing up, I also was constantly surrounded by white evangelicalism. So I attended a private Christian school from the time I was in preschool, all the way through college. So I’ve been around whiteness a long time. And in all kinds of different denominations, let me tell you, Brené. I’ve seen them all. I learned the hard way. I learned the hard way that there is a deep difference between the Jesus that black folks worship and the Jesus that white Christians worship.

BB: Tell me the difference.

AB: The Jesus that black folks worship doesn’t ask questions like, “But does the gospel really have anything to do with race and justice?” Black Jesus doesn’t hesitate to say, “Black Lives Matter.” Black Jesus stands for the oppressed, cares about those who are most marginalized, and not just cares, Brené. Sits with, lives with.

BB: Fights for.

AB: Fights for, is angered by the mistreatment.

BB: Protests.

AB: Protests with.

BB: Yes.

AB: Right?

BB: Yeah.

AB: While white Jesus is primarily interested in self. In self, and money and capitalism and in self, and how much can I get? How much power can I hoard? It’s all about self. And it’s all about the preservation of self. Of ego. Mostly power.

BB: Mostly power.

AB: Mostly power, a deep desire to wield power over… Power over others.

BB: Right. Yeah, it’s interesting because I think of Jesus, I think of power too, but I think of power with and power from and power shared and power within.

AB: There you go.

BB: I don’t think of power over.

AB: Power over is white Jesus.

BB: Yeah.

AB: Power over is a Christianity that would say, “Slavery is the way God intended things to be.”

BB: Well, it did say that, right?

AB: Exactly, right?

BB: And it continues to in some corners.

AB: Absolutely, absolutely.

BB: Do you think also there is… I’m going to use, I hope I’m allowed to worship the black Jesus because that would be my Jesus too.

AB: I wish the whole world would.

BB: Yeah, because I think as you came up in that environment, I came up in a very liberation theology, Jesuit, no playing, not just witness, but fight, like that protest. That was… I remember growing up in New Orleans where the Jesuits supported the Black Panthers, where they were… It was just a very different… But that’s different than a conservative white evangelical thinking.

AB: Yeah, my experience as a black woman who has grown up particularly in the era post the Civil Rights movement and post perceived integration.

BB: Yes.

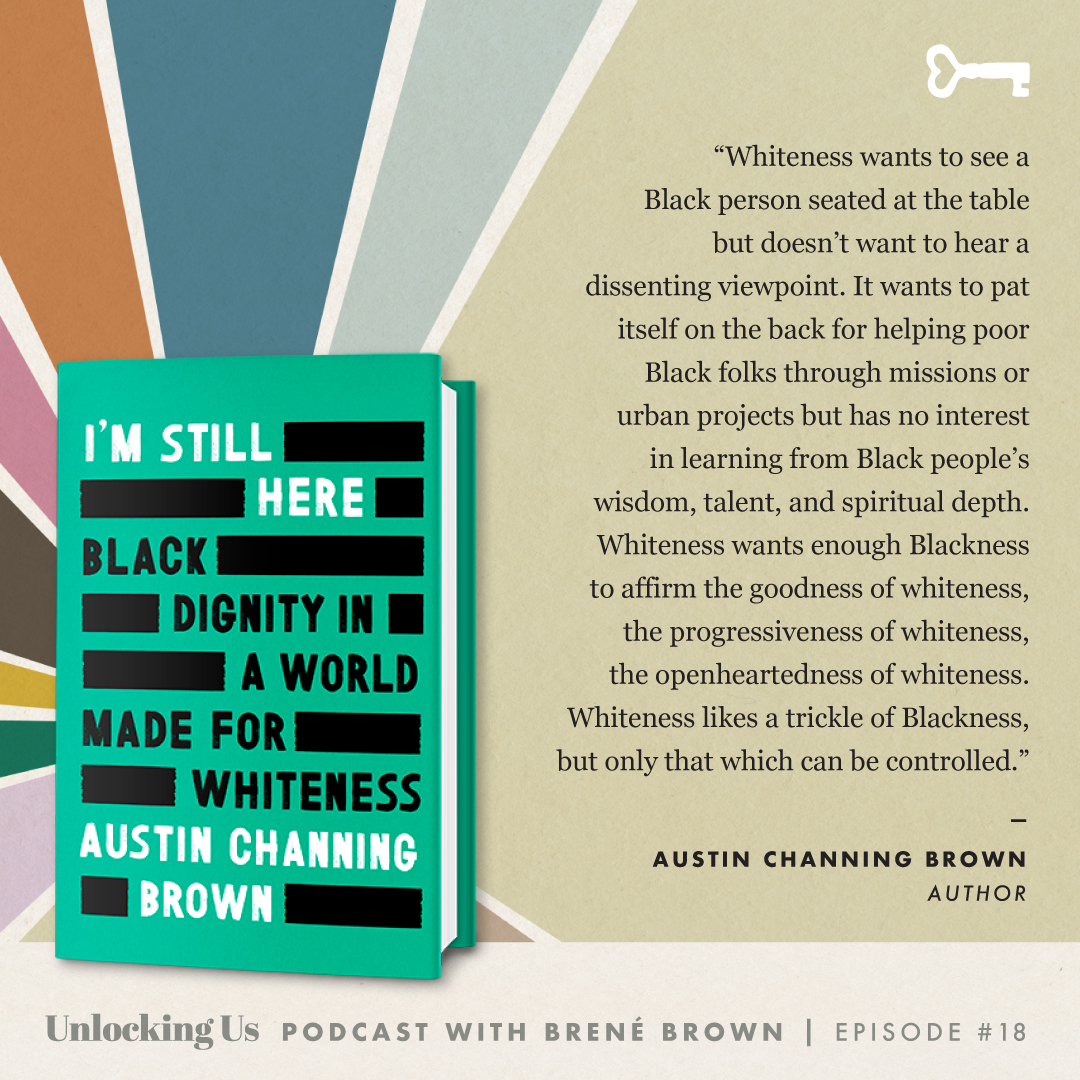

AB: Right? My experience is that white folks want just a pinch of blackness, just a splash, a smattering, a little toss of confetti of blackness in order to affirm itself. In order to affirm its own goodness, in order to affirm its rightness, in order to get rid of any feelings of guilt, in order to keep itself comfortable. So that it can continue to practice power over.

BB: Yeah. And justify it.

AB: It just wants to feel good about it. [laughter]

BB: Feel good about itself, yeah. I’m asking Austin just, if you’ll be generous with us, and that’s a big thing to ask right now, if you will read these two paragraphs from, I’m Still Here’that I think need to be tattooed on the world.

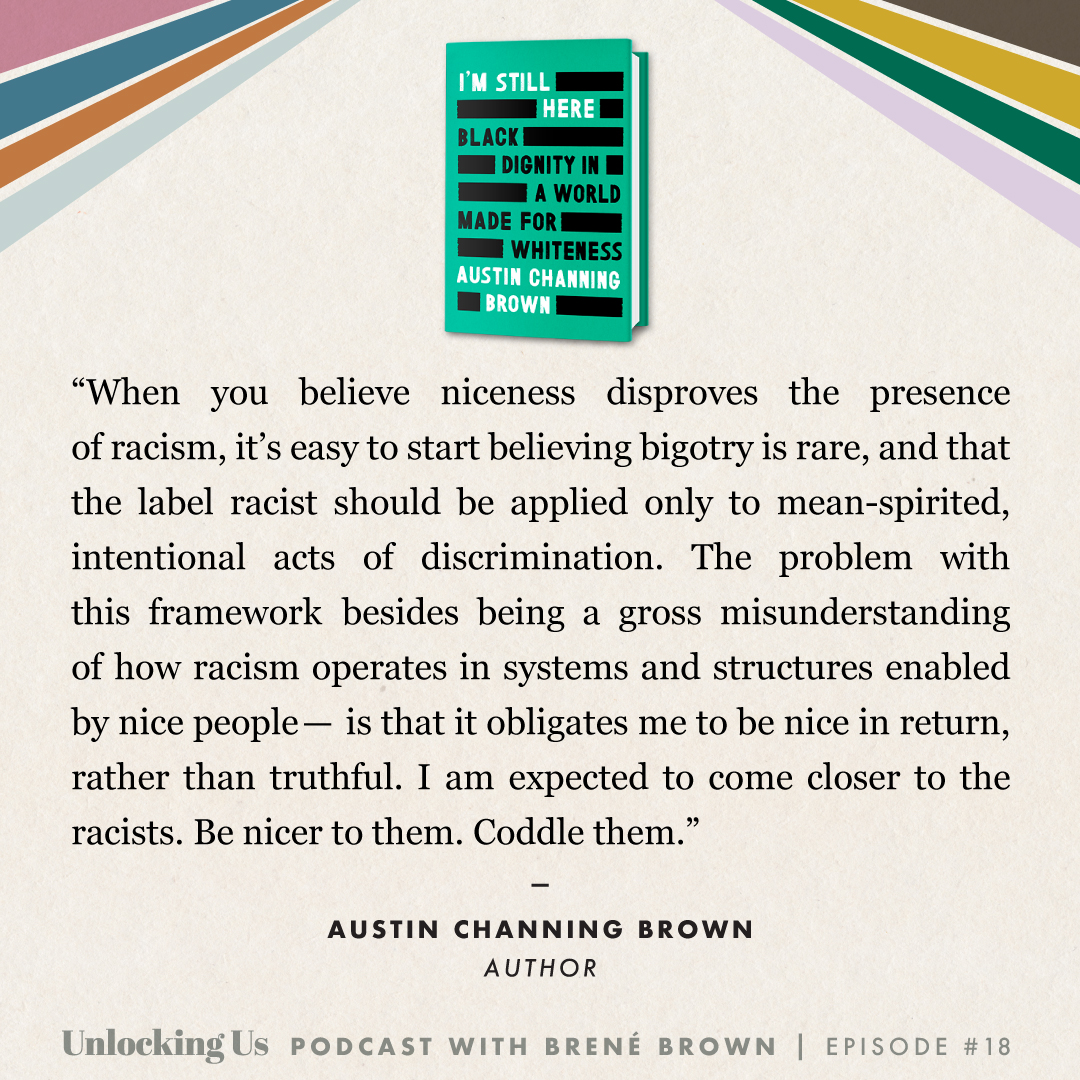

AB: I’m happy to, this is from the chapter, “Nice White People.” “When you believe niceness disproves the presence of racism, it’s easy to start believing bigotry is rare, and that the label racist should be applied only to mean spirited intentional acts of discrimination. The problem with this framework, besides being a gross misunderstanding of how racism operates in systems and structures enabled by nice people, is that it obligates me to be nice in return rather than truthful. I am expected to come closer to the racists, be nicer to them, coddle them. Even more, if most white people are good, innocent, lovely folks who are just angry or scared or ignorant, it naturally follows that whenever racial tension arises, I must be the problem.

AB: I’m not kind enough, patient enough, warm enough, I don’t have enough understanding for the white heart, white feelings, white needs; it does not matter that I don’t always feel like teaching white people through my pain, through the disappointment of allies who gave up and co-laborers who left. It does not matter that the well-intentioned questions hurt my feelings or that the decisions made in all white meetings affect me differently than they do everyone else. If my feelings do not fit the narrative of white innocence and goodness, the burden of change gets placed on me.

AB: When this narrative of goodness is disrupted by the unplanned utterance of racial slurs, jokes, rants or their kind, whiteness has perfected another tool for defending its innocence. I call it the relational defense; it happens in media all the time. A government official, teacher, pastor or principal is caught on tape saying something that is clearly racist, but rather than confess and seek transformation, the person defends their goodness by appealing to the relationships of those who “know” them. “I’m not racist, just ask blank, she knows me.” My family and friends know my heart, they will tell you I couldn’t be racist. I have a black spouse, child, friend, I don’t have a racist bone in my body.”

BB: God. Let’s talk white supremacy and niceness. It’s so about cognitive dissonance for people. Do you know the tension of these two things that… Let’s just take all the bullshit out and let me just say, for me, when I do something that makes clear my unacknowledged, unowned privilege, I feel two things at one time: One is shame, and one is, “But I am a good person. I am a good person.” But you know what’s true? I am a good person, and I have a lot of privilege, and a lot of support for structural racism that I don’t even know exists inside me. Those two things are true.

AB: You know what’s also true Brené? You may be a good person, but you can be a better one.

BB: Oh my God, I can be a better person and… [laughter] And… Yeah, no. And if I am a decent human being and I believe that about myself, and, I get called out on something I’ve done that’s sexist, racist, homophobic, heterosexist, xenophobic, whatever, I get called out on, do you know what I do in those moments? Because you know I have those moments in public all the time, like, [laughter] on film, because I walk into those conversations and I just have them. And you know what my mantra is? I have a secret mantra.

AB: Please tell.

BB: I’m here to get it right, not be right. I’m here to get it right, not be right. I’m here to get it right, not be right. And so, if I have to get it right, I have to listen and learn. If I have to be right, I have to use my niceness and my decency to defend my behavior.

AB: I tell people all the time that the work of anti-racism is the work of becoming a better human to other humans.

BB: Oh my God, can you say that again and slow for everybody?

AB: The work of anti-racism is becoming a better human to other humans, that’s what we’re doing. That’s what the work of anti-racism is.

BB: That is the work.

AB: We’re becoming better humans so that we treat other humans better, [laughter] that’s what we’re doing here. So being called out, even though it feels terrible, it feels terrible Brené, nobody would argue that this is like a feel good… That it’s a feel-good moment.

BB: No.

AB: Right? But we’re also not interested in trying to hurt your feelings, we’re not interested in trying to manipulate you, we’re not interested in all the things that anti-racism educators get accused of. We are saying, “I think you have capacity to be a better human, would you? Would you accept that invitation?” And I can’t tell you how often the response is, “but I would rather just be nice and polite, if that’s okay.” [laughter]

BB: Yeah, no, I got to tell you…

AB: That was the response.

BB: I’ve got to tell you, nice and polite is a scourge. It is… And I’ll tell you… I’ll tell you where I’ve seen it. We’ve got a… I’m not going to lie, we’ve got a shit ton of it in Texas.

AB: Sure.

BB: But the South.

AB: Yep.

BB: You know the nice and polite culture of the South…

AB: Oh, you’ve got it down.

BB: Yeah, it’s just… And that’s why when I go back to this cognitive dissonance. So we know cognitive dissonance, when you have to hold the tension of two competing ideas, is one of the most physiologically and emotionally uncomfortable feelings. Our body is wired to jump out of it as fast as we can like, “Oh, my God, these conflicting messages right now, I have done or said something that’s dehumanizing or racist or it supports a system that dehumanizes others. I am a good person; I am trying my best.” If we could just jump out of that to, “I am a good person, so I’m going to be quiet and learn and apologize and make amends and take action.”

AB: There you go.

BB: Instead of… There are two lanes, and I’ve not thought through this, I want to think through it with you. It seems like there are two tap-out buttons when we’re in the discomfort, right? There is the relation… What do you call it? The relational…

AB: Relational defense.

BB: Relational defense.

AB: Yep.

BB: Look, I’m friends with Austin Channing Brown like…

AB: She, call her. She would say, “I am not racist.”

BB: She would say… Yeah. No, yeah, it is the relational defense. So that’s one tap-out button, there’s several top-out buttons, but they’re divided, I think, into two sides. The next tap-out button is, “I am a good, loving person, look at the money I give to charity, look at the work that I do, I’m a good person; something’s wrong with you,”

AB: Right.

BB: The other tap-out button, which people don’t understand is also, delivers us from this thing is, “I am sorry. I am wrong. I will work every day to be better. I will learn from you, but I will value the labor and the work you’re doing to teach me, soulfully, monetarily, your time… ” That is also… And that’s a tap-out button, that is not a deep tunnel to nowhere. That’s a tap-out button that makes us, in your words, better humans. That makes me a better mom, a partner, a better person of faith.

AB: It makes you more human. It makes you more human because the truth is, is that we all mess up, Brené, we all mess up. I’m a black woman and I get disability stuff wrong. I’m cis and I get queer stuff wrong. We all get shit wrong [chuckle].

BB: We all get shit wrong.

AB: We all get shit wrong.

BB: Takeaway number one from the podcast today.

[laughter]

AB: We all get shit wrong. The question is, have you built the capacity to care more about others than you care about your own ego? Will you choose…

BB: Oh, my God, that’s the question.

AB: Right? Will you choose to protect someone else over protecting your own ego?

BB: And the worst thing is the ego begs for our protection but is not our friend.

AB: It’s not our friend. It makes us worse humans [laughter]

BB: It makes us worse humans, but it tells us, “Protect me, or you will know pain like you have never known.” But it’s a liar.

AB: Right. Well, sort of, right? So, to protect someone else is to invite pain.

BB: But do you think that… See, for me, that pain is an opening.

AB: Yes.

BB: That pain is an expansive pain where I, an intimacy, a connected pain.

AB: Yes.

BB: As opposed…

AB: Well, that’s why I say it makes us more human, right? Like it is…

BB: Yeah, okay, I get it, yeah.

AB: And that’s part of what white supremacy is stealing. Part of what white supremacy is stealing is your ability to see, to feel, to hear, to hold in high esteem other people. There are no roadblocks to two of those buttons that we tap. The relational defense, white people can go there immediately.

BB: Right.

AB: Right? The “I’m a really good person and I can’t believe you’re attacking me like this.” You can go there immediately. There is a hurdle that you have to overcome in order to access the desire to protect someone else over yourself, and that hurdle is white supremacy. Because white supremacy doesn’t value the other life as much as you value your own. That’s the core of white supremacy, right? “I am white and therefore I am better, I am right, I am holy, I am good, I am innocent, I am… ” Right? “And you are inferior…” That is how we built white supremacy. “I am better, I am superior, you are inferior.” But in order to access this desire to protect black lives, the desire to be taught by black lives, the desire to sit at the feet of black people, the desire to pay black people for their labor, the desire to make sure that America actually lives up to its own creeds, you’ve got to first get over the hurdle, which is destroying the idea that we are not equal. And I know innocent, good, well-intentioned white people do not want to believe for one second, Brené, that they don’t consider themselves equal to another human being.

AB: But the truth is, if in your life, you can be called out by your white friends or your white co-workers or your white supervisor, if they can say to you, “Hey, you know what, that was really good, that presentation you gave was really good, but I just want you to tweak this one thing.” If the white people in your life can say you’re not perfect and you don’t lash out at them, but the black people in your life would suggest [chuckle] that you could do something better, and all of a sudden you want to rip their heads off, you’re not at equality yet. You’re not at equality yet, and it’s because you’ve got to get over white supremacy. You’ve got to dig deep and really believe. Not just in your head. Not like my parents told me that all people are equal when I was a kid, but you got to really dig deep and decide that against your initial inclination, [chuckle] I am going to decide right now in this moment of having been called out, that I am not superior. My ego is not superior. What I want is not superior. What I need is not superior. In this moment, I am going to decide that the face in front of me has something, knows something, can share something that I am desperately in need of because I am not superior.

BB: It’s just truth. They’re just, I mean… Thank you for listening to the podcast.

[laughter]

BB: I mean, this just… I mean, it’s just… I just… That’s truth and… Can I ask a bunch of questions?

AB: Please.

BB: Okay, so you said, “Two easy tap out buttons, relational defense, I’m a good person defense.”

AB: Yeah.

BB: But the huge barrier to the setting my ego aside is white supremacy, and white supremacy is a complex, I mean, a complex…

AB: Yes.

BB: It’s like asking to me, explaining white supremacy is like asking a fish to describe water.

[chuckle]

AB: That’s right, that’s right.

BB: What role does proximity play in being able to say, I… In dismantling white supremacy… What role does it play, or does it play a role in your mind?

AB: It can. It can play a role.

BB: If you had to define proximity, how do you define proximity?

AB: You know what? I think that… Here’s what I think people hear.

BB: Okay.

AB: When we talk about proximity is, do you have a black friend?

BB: Oh, you think that’s what white people hear?

AB: Oh yeah, I think that’s what white people hear. I think white people hear, “is there a person of color in your life that you are literally proximate to?”

BB: Okay.

AB: That is in your group that you’re having coffee with or that you’re… Right? And that understanding of proximity is dangerous.

BB: Yes.

AB: It’s dangerous for black people. [chuckle] It’s dangerous for people of color. And it places… It warps the relationship; it puts the burden of teaching on black people. It can become manipulative. It makes the person of color responsible for changing your heart and mind.

BB: Yeah.

AB: You know?

BB: But you think that’s what people think of when they hear the word proximity? Even like, I have a black partner, or I have…

AB: I do. I do.

BB: Okay.

AB: And again, I want to keep in mind that most of my experience is in faith-based organizations. And so often, after we finished the MLK day service, what is said is, “Can you reach out, and can you reach across the aisle, or can you invite somebody that you haven’t met before to a coffee?” Or whatever, right? So maybe it isn’t that word. Right? Maybe it’s just too often the example that we use.

BB: That’s helpful. That’s… Yes, that’s helpful.

AB: You know?

BB: That makes sense to me. So, what is proximity? How would you define it in real anti-racism dismantling terms?

AB: I’m…

BB: Or would you?

AB: I’m not convinced it’s necessary. And there’s a lot…

BB: Say more.

AB: First of all, I just want to announce there’s a lot of anti-racism educators that would deeply disagree with me. I’m not convinced that’s it’s necessary, Brené. I think that white people are not children. I think grown white people are adults who can think critically on their own. Who can read books, and listen to podcasts, and study history, and be self-reflective, and get a therapist, and look at the world, and say, “Something’s not right here, let me change the way I vote.” Right?

BB: Yeah.

AB: “Something’s not right here, let me give to an organization that I have researched who is trying to change this. Something’s not right here, let me go [chuckle] do.” I think in that process, when learning, when curiosity has come first, you find yourself in proximate relationships that do not benefit you. And I think maybe that’s the core of this proximate thing, right? Is that, white people hear that and think, “Great, let me go find a relationship that benefits me.”

BB: To prove my relational hypothesis.

AB: Right. Or to prove that I’m nice and that, at least one black person really likes me. I think there’s something missing from our proximate conversation, our national proximate conversation. That is not discussing what the power dynamics are in that proximity.

BB: Yeah, and, God to me, I’m almost going back to like my undergrad sociological theory classes on Exchange Theory. Like, I can see the using, the manipulating, I also see right now on social… And it’s probably the relational defense, I also see a running toward highlighting friends of color.

AB: Yep.

BB: And how that…

AB: It’s still for self, Brené. It’s still for evil.

BB: It’s still for self, that’s it, that’s it, that’s where I was trying to get to, it’s still doesn’t seem other-focused to me.

AB: That’s right. That’s right. And that does not serve the cause of justice, freedom and dignity of others. So, in that proximate relationship… So, my question would be for all white listeners is, in that proximate relationship, what are you giving?

BB: Hard stop.

AB: What are you…

BB: Yes, what are you giving period? Question, yeah.

AB: Yeah. Yeah. And there are… Actually, you know what, that’s not true Brené. I was about to say that there are white people in my life and we’re just friends and that’s it, but it’s not true. Every white friend that I have, and y’all can imagine that list is real small, but they do exist. I have a white friend, Brené. No, I’m kidding. [chuckle]

BB: Yeah, you’re doing your work Austin. [laughter] You’re doing your work.

[laughter]

AB: Every white friend I have because they see me as fully human, pursues racial justice in their own life. Whether that means… Whether I’m there or not.

BB: Oh, my God.

AB: I think that’s what I’m trying to get to.

BB: Yes.

AB: Whether I am physically present, whether we are in literal proximity or not. The white people in my life who I would call friend are doing the work. If I disappeared from the world tomorrow, if I just like moved to New Zealand and didn’t write another word, didn’t say another thing, just sat on a hill somewhere, you know? The white folks in my life would still be doing the work. Because it isn’t about me personally. It isn’t about proximity to me.

BB: Yes. And being friends with you is not the work.

AB: Yes.

BB: That’s the part that feels very, very using to me.

AB: Yes.

BB: Yeah, so your white friends… If you’re on the hill in New Zealand, I’m coming to visit you for sure. Yes, and we’re going to hike and go see the Hobbit Holes and do all kinds of great stuff, yeah. But if you’re on the hill in New Zealand, your friends are going to keep doing the anti-racist, the justice work.

AB: Yeah.

BB: Their relationship with you is not a proxy for that work.

AB: That’s right. They are still going to teach their kids how to be anti-racist. They’re still diversifying their bookshelves. They’re still talking to their teachers about what the curriculum looks like. They’re still saying that they want more diverse teachers in the school. They’re showing up at protests around immigration or pride or a million other broken systems in this nation. They are doing the real work. And I am not the work.

BB: Oh, my God, it’s just…

AB: And I think that’s my issue with proximity… With the way that we talk about proximity, I don’t know…

BB: No.

AB: Right, I think we could redefine it, right? I think we could make it more useful. But I think where it currently falls short, is that it still makes me the work and it still requires me to do work that ultimately does not serve the cause of justice.

BB: And is it not actually when your immigrant friend or your black friend is the work, is that not ultimately dehumanizing too?

AB: It’s so dehumanizing.

BB: Austin’s doing the “praise Jesus” move and I can’t… You can’t see her but we’re on Zoom and she and I have both done a lot of hand raising in this, I wish you could watch us. Yeah, but isn’t that… I guess that’s why I was asking about proximity, because I’ve got fear about stepping on it as a white person trying to learn and do the work, but I’m seeing it used in this really weird way that feels…

AB: It is, that’s why… So this is not a rule, right? White people really like rules when it comes to racial justice, so that they can do it the correct way.

BB: Oh, my God, yes.

AB: You know what I mean?

BB: Yes.

AB: So what I’m about…

BB: But no, no, no, no, no I’ve got to stop you. White people like rules not so they can do it the correct way.

AB: Yes, tell me.

BB: So yeah…

AB: Why do white people like the rules? Let’s talk about this.

BB: So that we can protect ourselves. It’s not to do the work the right way. It’s so that when we do something, like you told me African-American was the right thing.

AB: Brené.

BB: You told me that you don’t capitalize black. You told me that I could say this, so we want the rules.

AB: Brené.

BB: The rules…

AB: I hear this all the time.

BB: Yes, the rules are the fence around the ego. You told me where I could go and where I couldn’t go. And now you can kiss my ass because these were your rules.

AB: Right.

BB: You told me… Oh, let me give you an example right now. People telling Dr. Bernice King what… White people telling Dr. Bernice King, what her father meant. So what… [laughter] You would not want to see the face Austin…

AB: I need you all to be able to see my face right now.

BB: So here’s the thing, “Well, Martin Luther King told us the rules, he told us that we should be peaceful.”

AB: Brené, that’s good.

BB: Yeah, and so now… So, I just want to make that because the people I talk to, even my students for the last 20 years, graduate students, me teaching classes on race and gender and policy are saying, “Could we get a list?” [laughter]

AB: Right? Right.

BB: But you know what, I will also go on to a PFLAG website and say, “What terms are we supposed to be using right now?” Some of it’s good intentioned that I want to be in the know, but a lot of times we want rules because they protect us and they are weapons for our defense.

AB: Wow. That’s good. That’s good.

BB: Yeah. I want them too, I want rules, don’t you? Wouldn’t you love some rules, if you just follow this… Yeah, that’s good.

AB: That would be delightful, actually.

BB: Yeah.

AB: If I could get the Black Handbook, that would be really wonderful, and you’ll survive in America, [laughter] as a Black woman. Where is that handbook, please someone? That’s good Brené. So this is not a rule, right? [laughter] This is not a rule. But when I hear anti-racism educators talk about proximity, the framing that they typically use is, “Are you the white person in the minority? Are you in the minority?”

BB: In your proximate situation?

AB: That’s right.

BB: Yeah.

AB: Or are you… Are you having to submit to the authority of someone else? Are you having to follow the cultural rules of another group? The core of that proximate question is, are you learning in real-time, how to let go of your own supremacy?

BB: Those questions make sense to me. We… We learned… In social work school, we learned that proximity is the relationship with a person in their geography or yours, their emotional geography, their physical geography. Where is the relationship in terms of geographical terms? So, what do you think about that question?

AB: What’s hard for me? So, in faith-based communities, the way… Most White people immediately ask, “So should I go to a black church?”

BB: Yeah.

AB: Right?

BB: That makes sense. Yeah, that makes…

AB: White Christians. Right? White Christians are like, “So, do I need to pick up my family, and go to to a Black church? And, no. [laughter] Because I don’t want to a flood of white folks at the black church, because that’s a beautiful protected space that is not for you.

BB: And not… And definitely not for you to check off something you need to do and be there as observers and box tickers. I think that’s a… I think that’s a big issue.

AB: Right. So there’s… I’d have a hard time naming a black church where there isn’t a white family. But that white family has been there for years, they ain’t going nowhere, they ain’t… [laughter] This isn’t a project, this isn’t a trend, they’re not trying something new. And so, I… And so, that’s why… That’s why I struggle with even the notion that white people are in this proximity but are in the minority, is how does their presence still change the dynamics of why people of color had this space in the first place?

BB: Yeah. That’s right.

AB: I… I… Honestly Brené, I just want to put the onus on white people and say, “Get it together, grow up, be mature, start learning, start reading, start researching.” Because I feel like eventually your decisions, your actions, will put you in proximity to issues that you are passionate about.

BB: That’s right.

AB: If you are passionate about immigration, eventually you’re probably going to meet someone who’s undocumented, right? But by the time you do so, hopefully you will come with a body of knowledge that doesn’t make that person the work, it makes immigration reform the work.

BB: That’s right. That’s right. God, I could just talk to you for days.

[laughter]

AB: Same. Same, same, same.

BB: I mean days. Okay, you’re just an incredibly important thought leader. Where can people find you? Support you? Learn from you? Tell me everything, TNQ, tell me everything.

AB: Yeah. So, one of my favorite projects has been The Next Question, which is my TV show, which Brené came and hung out with us y’all, and it was a fantastic conversation. It’s free, all episodes are free. It’s at tnqshow.com. We interviewed Brené, we interviewed Nikole Hannah-Jones.

BB: Oh my God, that was so good.

AB: Right? We did Rachel Cargle…

BB: Powerful.

AB: We talked about abolition, we talked about education, we talked about social movements… It is… That is my baby. [laughter] The Next Question is my baby, but I also hope that it’s filled with conversations like the ones you and I just had, right, Brené? That it is digging deeper, it is asking hard questions that we don’t necessarily have answers to, but it’s trying to move beyond the 101 questions that typically show up in national media. So I encourage people to check that out.

BB: They’re just amazing.

AB: Oh I…

BB: Yeah, the convert… You know what I would do if I were listening? I would gather friends in a socially distanced way watch an episode, potluck it in a healthy way, and then talk about the episode. What landed for you? What do you have questions about? What does not… What makes zero sense to you? All the questions. Yeah, all the questions, right? But to watch The Next Question show with other people, to me, is so powerful. Show it in your classroom.

AB: Right. And a lot of people should take… Take out your notebook because these thought leaders are dropping books, they’re dropping names, they’re talking about how they learned, how their own process, their own journey. So it’s just so much to learn. I re-watched all the episodes after we filmed them, and I found myself like, “Oh, that was good.”

BB: Yeah, no, it’s good.

AB: That was a good point, Brené.

[laughter]

BB: And we talk about hard stuff.

AB: We do. We have to.

BB: I know.

AB: We have to if we’re going to grow.

BB: I think Austin when you said, the barrier to pushing the button over here, which is being a better human serving others instead of your ego, the barrier is dismantling white supremacy and everyone is like, “Okay, how do I do that?”

AB: Right.

BB: To me, The Next Question.

AB: Right.

BB: You sit down and watch that with your family and your friends show it in your classroom, have those conversations. It’s like every time you have an uncomfortable honest conversation, a piece of the system falls off.

AB: That’s right. That’s right. There’s no easy way through this, you have to be uncomfortable. You have to be. And I think there’s this misnomer, Brené, that people of color or people who are queer or like any marginalized body, that when we are learning about our own experience, that it’s easy. That we like delight in our pain or [chuckle]

BB: Do you think people think… Jesus, do you think… I bet people do think that. I bet people do think that. Yeah.

AB: I don’t think it’s like at the forefront, do you know what I mean?

BB: Yeah no, but I see that, yeah.

AB: But I think there’s this notion that learning about these things is somehow harder for you as a white woman than it is for me as a black woman. And like, no, I don’t enjoy reading about lynchings. I don’t enjoy reading about slavery, but I have to for my own survival and for my commitment to justice. Right, and so…

BB: And I would argue that I also have to…

AB: Yes.

BB: For those exact same reasons.

AB: Yes.

BB: And, and…

AB: So if we have to do this hard thing, why not do it together, Brené?

BB: That’s right. And to me, the difference between me reading about lynchings and you…

AB: Yeah.

BB: Reading about lynchings, there’s so many, but I can opt out of the collective trauma.

AB: That’s right. That’s right.

BB: But if I choose to stay in the collective trauma, I’m being a better human with other humans. Okay, so The Next Question show, I don’t want to lose this thread, okay.

AB: Yes, yes, yes, yes.

BB: Tell us about…

AB: The Next Question?

BB: I’m still… Book.

AB: Yes, I love my little green book. I love her so much. I really encourage people to see if I’m Still Here’is available at black-owned bookstores.

BB: Great.

AB: If you don’t need the Amazon discount, bypass that. If you need it, I understand. Boy, do I understand. We are in COVID land, so I understand. But if you can afford to, if you could check to see if it’s available at black-owned bookstores and buy from them, that would be amazing.

BB: We’ve got that resource up on social right now and on our website a list of black-owned bookstores, yeah.

AB: And then I hang out on all the… Not all. I hang out on three social media platforms, I’m on Twitter, Instagram and Facebook.

BB: Under @austinchanning.

AB: You got it.

BB: I just cannot say enough about, I’m Still Here: Black Dignity in a World Made for Whiteness. Everything that Austin taught us today, led us today. It felt like you, not the information, Austin… You feel like church to me. You do. You feel like church to me. You feel like what is good and true about love, about our faith, about loving each other, and I’m really, really grateful for you and this conversation, and I’m super grateful for you.

AB: Me too. I wish if there was one thing, there’s lots of things I wish I could bottle up and just hand to people so they could experience it, like black joy, and there are things that I wish I could bottle up and be like, “Here, here’s why you want to practice anti-racism.” And one of those things is what happens between co-conspirators.

BB: Oh my God. I just got goosebumps from head to toe.

AB: When you are equals and when you are partners and when you are in it together, and when you’re like, “You know what, if this all falls apart, we’re just going to have to fall apart together, we’re just going to deal together, we just… ” That level of intimacy, I wish I could bottle it and be like, “Listen, here’s what’s on the other side, here’s what’s on the other side.” I’m glad that…

[overlapping conversation]

BB: Here’s what’s on the other side. Yeah, I mean, and like, yes, jail, New Zealand. My preference would be… My preference would be New Zealand, but…

AB: I’ll try that first, but…

BB: I’ll go…

AB: Knowing you and me, I feel like jail is…

[laughter]

BB: Yeah, and then they’ll be like, “Brown?”, and we’ll both be like, “Here.”

[laughter]

BB: Yes, we both… Yeah. I want to invite you to do this, you can say no, but I have these rapid fire 10 questions that are just personal. Some are fun, some are serious. But I really think we get dangerously close to dehumanizing thought leaders and activists as…

AB: Yes.

BB: Thinking machines…

AB: Yeah.

BB: Not real people…

AB: Yeah.

BB: So, are you ready? Will you do this with me?

AB: I am. Let’s do this.

BB: Okay. Fill in the blank. Number one, vulnerability is…

AB: Hard. Why?

BB: Number two.

[laughter]

BB: I mean, why, indeed. Number two, your called to be brave, but your fear is real and it’s stuck right in your throat. What’s the very first thing you do?

AB: Flip a coin between my fingers, which is what my dad taught me to do at my very first spelling bee, when I was afraid to get up and say my word, and he handed me a quarter and he said “Just flip this between your fingers.”

BB: Oh my God. [laughter] Spelling bee strategy. Okay. [laughter] Number three, what is something that people often get wrong about you?

AB: That I am serious and angry and [laughter] it just couldn’t be further from the truth. I am all about joy and humor, and if I could have chosen my career I would have been a stand-up comedian.

BB: Oh my God. I would have gone to see you. [laughter] Okay, last show that you binged and loved on television?

AB: Dead to Me.

BB: Oh God, it’s so good. Okay.

AB: So good.

BB: Favorite movie or one of your favorite movies?

AB: That’s impossible.

BB: I know.

AB: I really love movies and I really love all kinds of movies. I love black and white movies and musicals, I love comedies, I love romance, I love action. Right now, I am obsessed with “end of the world” movies.

[laughter]

BB: That fits. Let me do a Freudian analysis with you. Okay, so what is something that if you flip past it, not that we flip channels anymore, but if you did, you would always watch?

AB: Here’s what I watch. I would not say that this is my favorite movie, but it’s one that I watch all the time. I watch this almost every night as I’m falling asleep. “2012”, where the world ends in the year 2012… And they survive by going to Africa… Sorry to anyone who hasn’t seen it yet. Right? I love it, I’m here for the whole thing.

BB: I’m going to send you some more face masks. Okay. [laughter] A concert that you’ll never forget?

AB: Prince.

BB: Favorite meal?

AB: Oh God. Soul food. That way, I can just include all the things. Give me the fried chicken and the macaroni and the candied yams and the…

BB: Collard greens.

AB: Hello.

BB: Yeah. [chuckle] Okay. What’s on your nightstand?

AB: I actually have two. [laughter] Because it is overflowing with books. It has books, pens, at least four notebooks, my happy pills, some Chapstick, and a teeny tiny little lamp.

BB: Perfect. Okay, a snapshot of an ordinary moment in your life right now that brings you…

AB: Changing my kid’s diaper.

BB: True joy.

AB: Oh, well not joy. Okay, my kiddo is learning how to put sentences together…

BB: Mm-hmm.

AB: And so he does this thing, where he’ll include real words at the beginning of the sentence, and then the middle will be baby talk, so he’d go “blah blah blah blah blah” and then there’ll be real words at the end of the sentence.

[laughter]

AB: So if he asked for water, he would say “Mommy I blah blah blah cold waters.” [laughter] I’m sorry, what? [laughter]

BB: Okay, that’s so cute. You should tape that so you have that forever or film it.

AB: I should.

BB: Yes.

AB: I’m going to try to do that.

BB: And then something haunting like his rehearsal dinner or something, you could play it… [laughter] Okay, one thing that you’re deeply grateful for right now?

AB: Protesters.

BB: Amen. Okay, Austin Channing Brown, host of the TV show “The Next Question”, author of the book I’m Still Here: Black Dignity in a World Made for Whiteness, one of my very favorite human beings, church, thank you, thank you for sharing your time with us today.

AB: What a joy to be here.

BB: Thank you.

[music]

BB: Thank y’all for joining me with Austin in this conversation, it’s just… We’re going to get there, we’re going to be better humans with better humans, we’re going to get there, and it’s going to be hard and uncomfortable and painful and worth every hard, uncomfortable, painful step.

BB: Again, a reminder that on June 10th, Austin will be on my Instagram, which @brenebrown, and tonight will be on her Instagram doing the Instagram Live, which is @austinchanning. You can also find her on Twitter @AustinChanning, and her website is www.austinchanning.com, same with Facebook, and you can go to the show notes to learn everything about her, where you can find her and… Just get a copy of I’m Still Here: Black Dignity in a World Made for Whiteness. It will open your heart and open your mind. And… Fuel the fire. Which is exactly what we need right now. Thank y’all for listening to Unlocking Us. Go. Be brave. Be kind. Be awkward. Change the World. Speak up.

[music]

© 2020 Brené Brown Education and Research Group, LLC. All rights reserved.