Brené Brown: Hi, everyone, I’m Brené Brown, and this is Dare to Lead. I have to tell you, in I think every book I’ve ever written, I have used Charles Feltman’s definitions of trust and distrust to just capture this huge gauzy construct of what it means to trust people. His work for me is amazing. And today, I get to talk to him about his second edition of the book that I fell in love with, the second edition’s amazing. It’s called The Thin Book of Trust. And it’s literally, as we talk about in the podcast, a book that you can… When you get on your flight in LA, you’re done by the time you get to Chicago or Houston, and by the time you drive from the airport to the office, you can do something different to build more trust with the people in your life, on your team, in your leadership group. It’s just so practical, actionable, but at the same time, you know how a lot of practical, actionable, tactical stuff is also surface and kind of bullshitty? This is deep, meaningful, very Jungian in areas, but also so applicable to our lives. I cannot wait for you to hear this conversation.

[music]

BB: Before we jump into the conversation with Charles, let me tell you a little bit about him. Charles Feltman has been coaching, facilitating, and training people who lead others through his company, Insight Coaching, for 27 years. Prior to that, he led others directly for 15 years. Today, Charles’ work is concentrated in three areas, coaching individual leaders and leadership teams, designing and delivering leadership development programs, and helping people build trust at work. Clients have included leaders and teams in a diverse array of organizations from Fortune 500 companies to small and mid-sized companies, NGOs, and government entities worldwide. Charles is the author of The Thin Book of Trust: An Essential Primer for Building Trust at Work. Again, this is his second edition that just came out. It’s based on three decades of experience working with individuals and teams around trust building. It is just an incredible book, and I can’t wait for you to hear the conversation. Let’s jump right in.

[music]

BB: Alright, Charles Feltman. I have to say it is so exciting to meet you. We’re on Zoom, but in-personish.

Charles Feltman: Yes, in-personish exactly. And I’m really excited to be here with you too. Ever since I heard, I think, your first TED Talk that you did, I thought, “I really would love to just sit down and spend some time talking with Brené.” But of course, my idea of it was it’s just you and me over a cup of coffee.

[laughter]

BB: Well, I brought a few thousand friends along because I’m such a fan of your book.

CF: Well, I’m so happy that you’ve found it useful and you like it. I am a fan of all of your books too.

BB: So before we get into talking about The Thin Book of Trust, and before you teach us what we need to know about trust, I’m so curious, tell us your story. Where does your story begin?

CF: Yeah, I will say that it began in Arizona when I was born. It was a pretty typical family, mom, dad, brother, sister. I was raised by parents whose watchword was children are to be seen but not heard. So I have spent a good part of my life working with that like, “Okay, maybe I do need to be heard now.” Maybe it’s time, maybe it’s okay to be heard. But I grew up there, moved to Santa Barbara, California when I was about 10, and then by the time I finished high school, everything had changed. My mother and my sister were living in Florida, my parents were divorced. I had been there a couple of years, but I moved back to Santa Barbara to finish high school there. I was living in an apartment with two friends when I graduated and working as a house painter to make money. That was after I discovered that I actually had to pay rent.

BB: That’s a rude awakening, isn’t it?

CF: Oh my goodness, I have to pay rent. Wow, I better actually make some money and save it. And kinda loose ends. I applied to… Well, actually, I had intended to apply to universities, but I missed the filing deadline, application deadline. So at loose ends, went to a junior college for a semester. And then a friend and I said, “Okay, let’s do something different. Let’s go to Europe and travel around.” So the idea was we go a couple of months, then come back, and then I’d re-apply before the deadline ended. And that didn’t actually happen. What did happen was I spent two years traveling around Europe, different countries and working in different places, just an amazing time in my life.

BB: Wow.

CF: It was a whole set of experiences that I never would have had if I had just gone right to college. So that was the right choice at that moment.

BB: A real life-changing experience, huh?

CF: Yeah, it was. And in fact, the two of us, my friend and I, were only there for three days before I realized that I needed to actually set off on my own. And then shortly thereafter, I cut my long hair and shaved my beard because I didn’t want to look like all the other American hippies traveling around with their backpacks. I wanted to actually… Not that I had anything against that, but I wanted to look more like the people that I was hitchhiking with who would invite me into their homes, and I could have conversations with and learn about them and their culture. So that’s what I did for two years. I worked in different places, got paid under the table, of course, but was able to travel around and do that. And then I decided, well, it was about time to come home after almost two years. And so I did come back to the U.S. I did apply at some colleges and chose a place called Goddard College in Vermont, a wonderful sounding place and they gave me some good financial aid. So during the summer as I was waiting to go there, my then girlfriend got pregnant, and so we moved to Vermont and we got married in Vermont. And then six months later, we had our first daughter in Vermont.

CF: And at that point, it became pretty clear that I was not going to be able to continue going to this expensive private college. So we packed up and moved ourselves back to Santa Barbara, California, and I just applied to UC Santa Cruz. So that worked out really well. So I did some work, more time at junior college, showed up at Santa Cruz, it took me about four years to get through UC Santa Cruz, because I had to keep stopping school and going to work, or working part-time and school part-time.

BB: Yeah, of course.

CF: But I finished, and because I ended up with a degree in psychology, cognitive psychology, no less…

BB: Wow.

CF: What do you do with that? Pretty much the only thing you do with that is go to graduate school.

BB: Graduate school. I was going to say that, yeah. Cognitive psychology means graduate school. Yeah.

CF: Right, it’s not like you’re going to go to some company and say, “Hey, I have a degree in… ” The last work I was doing while I was at UC Santa Cruz was Student Services at UC Santa Cruz. I got a line on a job in Student Services at the University of Southern California. The cool thing about that was if you worked there for two years, you could go tuition-free to USC.

BB: Wow.

CF: So I put in my first two years, and actually, it was a really good experience in terms of work. And then I also started a graduate program and got this degree in something called Organizational Development. Just a fantastic program. So that four years outside of being in Los Angeles, which wasn’t my favorite place to live, was great because I had a great experience with the work. The leader of our department was really good. He really was a fantastic leader, he put together a great team, he ran the team well. It was, in some ways, unfortunate to get that at the beginning.

BB: It makes it a long road down from there.

CF: Yeah. Well, it was a pretty short road down actually.

[laughter]

BB: Really, to have a really great leader right out of college is a hard set up, to be honest.

CF: Yeah, yeah, it was. And in some ways, I had not had the kinds of experiences that allowed me to really appreciate that and take full advantage of it. But anyway, I graduated with a Master’s in Organization Development with a strong emphasis in communications technologies. And by that time, Silicon Valley was like this beacon to me. I really wanted to go work in Silicon Valley and be part of what they were all doing there. And so we moved back up to Santa Cruz and I got a job in a tech company in the Valley and had this sort of flip, opposite experience of great leadership. Everybody was running around like chickens with their heads cut off. I was lucky to talk to my manager, my direct supervisor, for 10 minutes a month. I had no mentoring. No one had time to mentor anybody, and I was supposed to be leading people and how do I do that? [chuckle]

BB: That’s tough.

CF: It was trial by fire. And I learned what I learned, and it wasn’t nearly as much as I would like to have learned from that because I was just trying to keep my head above water, but I did some good things and I think worthwhile things, and I ended up having a position in leadership and making my way through it. But then after about four years of that, my first wife and I split up and she took our kids back to Santa Barbara. We had another girl by then, so I was a father twice. And so I had these wonderful girls and when she left, it was like this giant hole in my life, even though I was working all this time. Boy, it was a hole.

CF: And so, just out of the blue, a headhunter called me up and said, “I have this company in Santa Barbara, California. I don’t know if you’ve ever heard of it, but I have this company down there and they would really like to interview you.” And I said, “Huh? Really?” And so, sure enough, about three weeks after that, almost four weeks after that, I was in Santa Barbara, had a job there, lived about two miles from my ex-wife or soon to be ex-wife, my daughters were coming back and forth between us, and it was like, “Oh, wow, this is great.” So yeah, I got to do another four years in the tech industry in companies in Santa Barbara. Towards the end of that though, I was really burning out, I wasn’t doing well. I think I tried on every piece of armor that you talk about in daring leadership. I was like, “Okay, let’s try this one on, see how it does.”

BB: Yeah. I’ve got my own dressing room, you’re not alone in that. Yeah.

CF: Yeah. So I’m going, “Ooh, look, this one has red beads in it. This is cool.”

BB: Yeah, and this one comes with a weapon, that’s even better. Yeah.

CF: Right. Yeah, exactly. So yeah, and I was burning out on the whole thing, and then carrying a lot of that armor around with me. I was struggling, quite honestly, in the job, the last job that I had. It was a leadership job, I was pretty high up in the organization, and I got fired. And it was one of those situations where looking back on it, I would have fired me too. So I went home that day, I was… Oh, let me just catch you up on another piece. I had met another woman and had re-married. So I was married again. So went home, walked in the door, my wife said, “Oh, you’re home early. What’s up?” And I said, “Oh, I got fired.” And she said, “Oh great. Now, you can start pursuing this thing you’ve been talking about about working for yourself for the last year.” I thought, “Oh yeah, I have been talking about that, haven’t I?” Then, “Oh, I’ve got this great package. So I’ve got the time, I’ve got the wherewithal to actually do that.” So I did. I started a consulting business and was doing this consulting stuff to differently, if so, management consulting. And it was okay. Consulting, of course, is all about giving people advice, and I love giving people advice. Who doesn’t? [chuckle] And I was getting paid…

BB: All of us.

CF: Paid for giving people advice, whoa. But then I ran into these people who are doing this thing called coaching around 1997, and it’s like a big light went off for me, “Oh, okay. You mean I can actually get paid for asking people questions? I can get paid to help them learn about themselves and become their own best advisors? Wow, sign me up.” So I started doing that with them, with that company, and did that for about four years. And before I went off on my own… Actually, the company dissolved but… I went off on my own and have been coaching ever since. I’ve been coaching leaders and companies all over the world, and leadership teams and doing leadership development training. So that’s what I’ve been up to, mostly, since 1997.

BB: 25 years, right?

CF: That’s about right.

BB: Yeah, tell me about your relationship with trust.

CF: Yeah, that’s a good question. So there are two aspects to that, maybe three. One is, as I both worked in companies and then began coaching, especially as I began coaching, I kept hearing trust come up over and over again, seemed to be… And so many of my clients had some kind of issue with trust. Maybe I was listening to it because I had issues with trust, which I would say that’s very likely. I think that was sort of how I was even listening and hearing that. So I had my own stuff to work on there very clearly. And so, as I went through a coach training program, part of it was we talked about trust and how that works. And so I had a framework or a foundation for working with people in a way that was productive and clear and crisp. And then I began to add to it and add my own pieces to it and bring in new stuff, and found myself doing a lot of work in that. But I never thought about writing about it particularly, I was just using it in my clients. And then the editor, publisher of Thin Book Publishing, Sue Hammond, called me up one day and said, “Hey, I read this paper that you wrote on trust. It was on your website, and I was wondering if you’d like to make it into a book? It’s a thin book, so you don’t have to expand it out too much.” I said, “Yeah, maybe I can do that. Sure. Why not? I’ll give it a shot.” Little did I know how hard it is to write a thin book about trust.

BB: God, a thin book’s hard. Yeah, it’s the Mark Twain letter. I’m sorry for the 10-page letter. I didn’t have time to write you a one-page letter.

CF: Yeah, exactly. Yeah, Sue kept coming as we were going through it, she kept coming back to me and, “Charles, we publish thin books. You need to cut it. We publish thin books.” I was like, “Okay, how about this draft?” “A little more out, a little more, a little more.” But through her guidance, I was able to get it out. And once it was out there, I found I had more and more people actually approached me specifically for that and about that. So, over the years, the book has been read by thousands of people. I know the marketing plan that the company has is, “Let’s get it into the hands of a few leaders and see what happens.” And so they, of course, pass it on to other people, they buy boxes full and have people in their departments read it. And then there are also all these coaches and consultants and facilitators and trainers who have purchased it and use it, and I hear from them pretty regularly, which is great, I love it. They call me up and say… Or email me and say, “Hey, I’m using your book. And it’s really helpful.” So in some ways, the book has taken on a life of the own. But at the same time, it’s a framework that I am very comfortable using, so I find myself using it quite often with my clients, especially when I’m working with teams.

BB: I have to say that I think I have quoted your definition of trust and mistrust in every book I’ve ever written, because there is just no finer, no better definition of trust than yours.

CF: Wow.

BB: And I’ve read a shit ton of them. I don’t know what the… I don’t know what the real measurement term is, but it’s been a shit ton. It’s been hundreds of definitions. So can I read your definition of trust from your book?

CF: Yes, please.

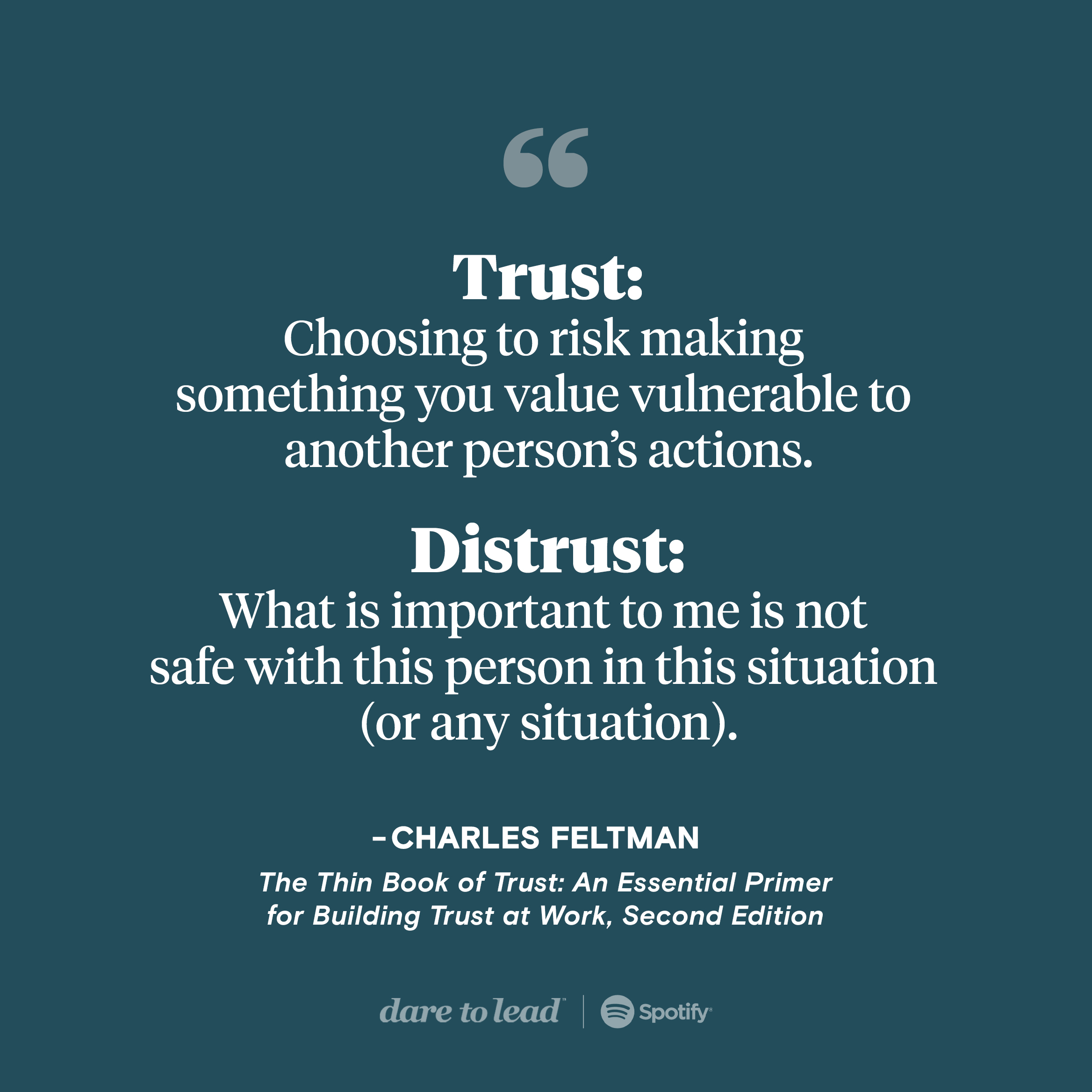

BB: “Trust is defined as choosing to risk making something you value vulnerable to another person’s actions.” God, that’s hard.

CF: Yeah, and this is why when I first heard you, your first TED Talk, vulnerability, trust, these are the lock and the key, they fit together that allow trust to happen. And there’s another quote, which of course, I don’t have a copy of my book in front of me, but it’s the quote from Walter Anderson at the beginning of the first chapter. Could you read that quote?

BB: Yeah, for sure. Hold on just a sec, I’ve got the book right here. “We’re never so vulnerable than when we trust someone. But paradoxically, if we cannot trust, neither can we find love or joy.” Walter Anderson. That’s everything I know about vulnerability right there.

CF: Yeah, me too. And that’s why I love working in that command of trust with people, is because I think everybody at work should experience a good healthy measure of love and joy. And trust is a huge part of that.

BB: Let me go on before we get started deeper in the book and give the definition of distrust. Can I read that from your book too?

CF: Yeah.

BB: This is the one that is just like a gut punch to me. “What is important to me is not safe with this person in this situation or in any situation.” God, “What is important to me is not safe with this person in this situation or in any situation.”

CF: Yeah, there’s a lot there, isn’t there. And that second part, in any situation is one of the things that I see happen so much in organizations and even with people that I’ve worked with, just coached around their lives, is it’s so easy to go from, “I don’t trust this.” to “I don’t trust you.” I don’t trust in this situation to I don’t trust you in any situation, and that’s the real disaster of distrust.

BB: Okay, I have a lot of questions here. Okay, I don’t even know how to frame this, but this is the biggest question for me in my work sometimes. Is it possible to trust people in some contexts and not in others?

CF: Yes, absolutely, and that’s a big part of the work that I do with my clients is helping them see that the trust is not all or nothing. If I have some framework or some way of making distinctions. You know you have your BRAVING framework? That’s a way of making distinctions. I have the distinctions that I use with people, but if you have some way of making distinctions and can see, “Okay, I may not trust this person’s ability to deliver what they’re supposed to deliver to me on time or what they’ve committed to delivering me on time. That does not mean that I don’t trust that they’re honest. I mean, they may seem dishonest because they tell me a date and then don’t deliver, but in fact, the ‘can’t deliver’ is a whole piece that is separate from their basic honesty, their basic integrity.” They may be feeling terribly out of integrity around that. I can still trust their competence maybe, or at least I can investigate that and see if there’s an issue of competence, and I can still trust that they care, that they care about me, or at least care about what we’re trying to do together in this company. So, I think that being able to make some distinctions around aspects of trust or what I call assessments of trust, and not lump it all together into one big thing.

BB: I think it’s a really important pause moment because when we had the braving assessment that we use, and this is kind of just what emerged from our data as elements of trust, when people are were talking about trust. I’ll tell you an interesting story, and I would love to get your commentary on it. We were actually, we haven’t done this yet because it has been such a debate until probably the last six months. When we were trying to add numerical value to the seven elements of trust, we ran into an argument in the literature. The academic literature, that said basically, trust elements are not additive, they’re not a sum or an average, they’re a product, and if anything is zero, the entire trust is zero. And that did not bear out in our research, like I could trust you around, let’s say vault, which we talk about confidentiality, but you may not be reliable on your deliverables because you over-commit, but it doesn’t mean I have an experience with you where you share things that are not yours to share or even with me or with other people. And so… First of all, I want to be clear, you don’t really believe it that is a product, you don’t believe if something is zero, everything is zero, is that true?

CF: You’re absolutely correct. I do not believe that and I’ve seen it many, many, many times. In fact, that’s what why when I work with people, and you know the manager or the leader who comes to me initially and says, “I don’t trust my direct report, or I don’t trust my boss.” And the first thing I do is walk through and try and help that person isolate the thing or things that are not trustworthy. The behaviors… Because, well let me tell you, just after the book first came out, I was on LinkedIn and there was these groups and there was an HR group there was an OD group. And in both of those groups, I asked a question, “Do you believe that trust is primarily a behavioral issue or a moral issue?” and I got about 40% behavioral, 40% moral, and 20% of the people came back and said, “I think it’s both.” If it’s the behavioral part and I actually happen to fall in the camp of it’s both, but the behavioral aspect of it is where I try and direct people’s attention. What behaviors are you seeing in that person, or what behaviors are you, the other person, seeing in me that’s generating this assessment of distrust?

CF: And so that’s why the framework… And again, it’s BRAVING framework or it’s my four domains. A framework helps people actually see that, it kinda pops out, “Oh, okay, this is the behavior. It belongs here. This is what I’m distrusting.” It’s not the whole person, the whole person is not morally defective, the whole person is just trying to survive, they’re doing what they’re doing, and I haven’t done any kind of study like this, but… I just got the sense of it. Having talked to many, many, many people in organizations, is that 90% of distrust arises because you’re doing what you do, and I suddenly see something that you do as untrustworthy through my lens, and now I’m going “Hmmm.” And then, of course, our great ability to try and find any more instances of that…

BB: Yeah, the confirmation bias.

CF: Yeah, and completely disregard anything that might contradict my assessment. Suddenly I’m distrusting you, but if I can help that person, if I can help me in some sincere situations, go back through and say, “Okay. So, what is it specifically? What’s the behavior or the behaviors?” And then it becomes a couple of things. One is, let’s go back to your example of the person who’s not delivering well on their commitments. I can actually set up some boundaries to deal with that, and/or I can go have a conversation with them that is not about I trust you or I don’t trust you. It’s about what’s going on with not being able to deliver on your commitments. That’s a whole different conversation.

BB: Oh my God, night and day.

CF: Yeah.

BB: I mean, as someone who studies shame, when you come at me around questioning my trustworthiness, that feels like… Even if you’re questioning my trustworthiness, that is a hijacked by the limbic system, assault on character, I really hear nothing you say after that.

CF: Yeah.

BB: Is that your experience as well?

CF: Absolutely, absolutely. And, in fact, there’s some research I saw that seems to indicate that while women, when that happens, pull back, they just want to put distance between them and that person, most men react with anger and aggressiveness to being accused of being untrustworthy, and my experience has kind of borne that out.

BB: I can see that. So tell me about the assessments, the four distinct assessments of trust that you have found. I think these are so important.

CF: So first of all, going back to that fundamental assessment, what I value… I know I’m making vulnerable here. It’s safe to do that, or it’s not safe to do that, is a risk assessment in a way. I’m assessing the risk of putting my… Whatever I value out there. So an assessment is by nature not a fact, but it can be based on facts. It can be based on evidence and should be in fact. A well-grounded assessment is well-based in facts, and in evidence. So the four assessment domains that I work with are, the primary one is care, which is the sense that my assessment that you have my interests in mind as well as your own when you do stuff, when you say things, do things, that you care about me. You have my well-being in mind. That’s fundamental, I think. If most people, in my experience, if they believe that of me, they’ll actually let me slide a little bit on some of those other ones.

BB: I can see that. We’re care starving.

CF: Yeah. And again, going back to certain behaviors in that domain that allow me to assess positively, yeah, I think that this person does have my interests in mind. They do care about me. And then the next one is sincerity, which is actually really broken down… I break it down into two. One is honesty, and all your honest, not only honest with the facts, but emotionally honest.

BB: That’s tough for people.

CF: Yes, and I love that… That’s one of the things I love about your work and your book is you just bring that out front and center. And then there’s integrity, so walking your talk, which is also often really difficult in an organization…

BB: For sure.

CF: Where people are moving at 90 miles an hour. I say something to Bob over here about what my plans are, and then I talk to Angie and I change my mind and tell Angie, “Okay, we’re going to go this way,” and Bob finds out from Angie that we’re going to do something different and goes, “What? What’s with the integrity in that? He’s speaking out of two sides of his mouth.” Simply because my behavior is that I didn’t go back, I failed to go back to Bob and say, “Hey Bob, I’ve changed my mind. This is why.” So even little things, little behaviors like that, I just want to put a pin in this one because I think you say in many places, but on one particular place, I remember reading something about, it’s those little… It’s the marble jar thing, right?

BB: Mm-hmm.

CF: All of these little behaviors, every interaction we have is an opportunity to build or possibly damage trust, every interaction. And so being able to be aware of what we’re doing, to be intentional about building trust is really important, [chuckle] fundamentally important.

BB: Yeah. Absolutely.

CF: It’s hard to do it when we’re on autopilot and we’re just doing what we do.

BB: Oh, God, yes.

CF: So…

BB: Lack of awareness.

CF: Yeah. So there’s me in this situation where I don’t go back and kind of clean up and make sure Bob understands what’s going on. A little, little thing, right? I’m moving too fast. I don’t think about doing that. And all of a sudden, there’s this damage to the trust. So that’s this domain of sincerity, integrity, and honesty, walking my talk, when I say then doing what I say I’m going to do in general. The third assessment domain is reliability, which is really related directly to keeping the promises or commitments that I make, which sounds really simple and straightforward on the surface… [chuckle]

BB: Yeah, it’s not.

CF: But it’s really, really hard. Again, fast moving, “Okay, I’ve got to make this commitment, right? Because my boss asked me to do this, but he’s also asking to do these other things, and then these other people are asking.” So it’s easy to get lost in the shuffle there without being intentional about both our yes’s and our no’s.

BB: I think that’s right. And I think so much damage to this area, to reliability and myself included, is over committing to an impossible number of competing priorities.

CF: Yeah, yeah. So I talk in the book a little bit about kind of a language of clear and complete requests, offers, and commitments. I talk about it as the cycle of commitment, and when we say yes to a lot of requests and we also make a lot of offers… Because generally, if we’re the kind of person who says yes a lot, and then we’re also often the kind of person who makes offers a lot, suddenly we’re snowed under.

BB: Let me just take a moment and just go yuck. Yes. Okay, so say that again. When we’re the people that do what, we also tend to be the people who do what? I’m blocking you as you’re talking, but go ahead.

CF: Yeah. [chuckle]

BB: It’s painful.

CF: So, my experience is that if we are the kind of person who really easily says yes without really stopping and thinking about it, we also tend to be the kind of person who makes offers to do things without necessarily thinking about, “Can I really fulfill this offer?” Because once I make an offer to you, and you accept it, you are going to hold it as a commitment that I’ve made to you. And I’ve coached more than one leader who didn’t quite understand that connection, so she would make offers to people to do stuff and just kind of in the back of her mind, her assumption was, “Well, if I don’t do it, it was just an offer.” which got her into all kind of trouble. They pile onto each other.

BB: I hate the way that you skip right from offer to commitment. That’s painful.

CF: [chuckle] But think about it. It is, isn’t it?

BB: Yeah, I don’t care for it, but go ahead.

[chuckle]

BB: I agree with you 100%, but I resent the implication. Go.

CF: [chuckle] So I’m curious. Just, what is that for you? Just that, what’s the catch?

BB: No, there’s no catch, it’s just true, and I’m learning it painfully every single day, but I have a very strong upbringing of, “Don’t disappoint people, be the good girl, say yes all the time.” Combined with a lethal mix of “Say yes to everything, because it could all go away tomorrow.” And layered with yet another death fear of not being in my integrity around commitments. So I’ll do it all and deliver usually. The two things I don’t like that I do, I will make myself physically sick, or I will take away time from my own health or my family to make good on shit I shouldn’t have committed to, or I’ll say yes and then have to walk that back after clearly someone has already felt that as a commitment.

CF: Yeah, and that has been me much of my life too. Actually pretty much all of my work in organizations, I was constantly… I was working weekends to try and keep up with all of the commitments that I’d made, the promises that I’d made to people, because I didn’t want to walk it back, and so the only solution is to just do it and, boy, that’s crushing. And it took me away from my family, which was the hardest part.

BB: Yeah.

[music]

BB: Okay, so let’s go back to when we make an offer and someone takes us up on it, that’s a commitment for them.

CF: Yes, yes, absolutely. So if I offer to show up on this podcast with you and you say, “Great,” and then I don’t show up, well I’ve just broken a promise to you, from your perspective. That’s a big one, so I would be considering it breaking a promise too, but there’s a lot of little ones, a lot of little ways that we can do that and not even think about it, and so we show up as being unreliable to the other person.

BB: It’s really helpful.

CF: And it goes back again to this intentionality about being trustworthy. There’s this moral commitment. This is the moral side of it, I make a moral commitment that I want to be trustworthy, but then after that it’s all about behavior, it’s all about being aware of what I’m doing and having some framework, some way of taking a look at myself and saying, “How am I doing?” And also, of course, being open to feedback, which is a big part of trust-building is being open to feedback, taking it in and acting on it.

CF: So yeah, that’s the reliability piece, the making clear and complete requests, which allows the person I’m asking to make a real commitment, to make a real promise, a genuine promise, as opposed to making a false promise that they can’t keep, and allowing them the space to say no, or the very least to say, “I can’t do what you’re asking me to do. I could do this and I could do this. If you take this stuff off my plate that you’ve already given me, I can do it by the time you want it and all that, but I can’t do everything.” But I can’t come back and say that if I don’t have a clear understanding of what I’m being asked to do. And that’s where I find that in probably 70% of the teams that I work with, that’s the number one place that they are hung up. They don’t make clear, complete requests of each other, and out of that, they make fuzzy commitments to each other, and trust starts to fall apart pretty quickly. So I do a lot of work around that, in that cycle of commitment.

BB: I really love that. Clear, complete requests. Wow, that’s powerful. That’s no joke. And that is an example, I think, of your work, where you say behavior, daily behavior, has to back up moral commitment to trustworthiness.

CF: Yeah, exactly.

BB: Wow. Tell me about the fourth one.

CF: The fourth one is competence, and we can trust in… And that’s the old, “I trust my wife in anything except doing brain surgery on me.” It’s around standards and ability. So if I trust that you’re competent to do whatever I’m asking you to do, that’s fine. If I don’t trust you, what happens? But here’s where things start to fall apart often. I will… And I, in fact, did this as a leader at times, as a manager… I would make an assessment that I didn’t trust someone’s competence to do something the way I wanted it done…

BB: Oh God.

CF: But I had neglected to tell them how I wanted it done… [chuckle]

BB: No.

CF: In a way that they…

BB: No. I’m going to have to just edit this out. Okay. Oh my God, say it again.

CF: So it’s about… It’s about standards and being having clear shared standards. So, building trust in that domain, the assessment domain of commitment comes from that. If we as a team have shared understanding of what our standards are, then it’s relatively easy for me to know if I have the competence that you can trust me, that I have the competence to do what my role is, or if I don’t, I can say… And this goes back to care, but we’ll get there in a second. If I don’t have the competence, I can say, “You know what? I don’t have that competence, I can’t do that, I need something more, I need training, I need whatever.” Which goes back to care, because if I don’t feel that you have my interests in mind, if I don’t feel like you intend good for me, then I’m going to be afraid to admit that I’m not able to deliver, I’m not competent. So then… I’ll tell you a story. When I first joined the first technology company that I joined, I had some idea of the technology, I don’t know like enough to be dangerous. And I suddenly found myself in this company where everybody was moving 90 miles an hour, and the coin of the realm was, I thought, was technical competency, knowing the technology inside and out.

CF: And so… But that wasn’t really my job but I thought that I needed to know that in order to be accepted, be trusted. So, when people would say something that I didn’t understand I’d make a note of it, when I had a free few minutes, I’d go look through a manual or a book or find an article or something to read about it and try and figure it out. Which was okay for a while, but as I went along there, I ended up creating a couple of situations where misinformation was passed on because I didn’t really understand what I was talking about, that had caused some problems. And one day, the director of engineering caught me in the hall and said, “So, Charles, it’s come to my attention that you may not know as much as you’re letting on, that you’re pretending to know.” And I thought, “Oh my God, I’m busted. I’m fired, I’m done here.” And he said, “Look, the engineers don’t need you to know at that level. That’s their job. If you want to know something, go ask an engineer. He or she will tell you way more than you ever wanted to know about that, but what you’re doing right now is creating this distrust. They don’t trust you.”

CF: Of course, now, looking at the domain of sincerity, I was not showing up as honest. I think I’m trying to show up as competent and I’m failing in the honesty department. So, that’s how those can interact and work with each other, so clear standards.

BB: But it’s so important because so often today, when I’m working with leaders, especially who get moved in to run teams where they have great leadership experience, great communication and trust building experience, but very little content expertise, their faking it is what unravels the trust in the team as opposed to saying, “I don’t know about that. What do I need to know to help you solve this problem?”

CF: Yeah, exactly.

BB: Yeah, and so we see that a lot. Let me ask you this question. I was going to ask you about competency and cleaning the kitchen, but I’m not going to go down that road because I… Would you trust someone when they say, “Can you clean the kitchen?” And for some reason they don’t include the sink and wiping down the counters and running the disposal.

CF: Have you been in my house? Have you been watching in my house? [chuckle]

BB: No, I’m just… It’s a universal dilemma. I love this… I can’t wait to get to the rapid fire because I’m so curious about how you’re going to answer, but this is the last thing I want to ask. We’ll have to do this again and dig into deeper conversation because your book is so good… There is a mythology around trust that is so dangerous… I run into it every organization I go into, which is, the more we trust each other, the calmer, more peaceful, harmonious things will be. And, God, that is a dangerous myth, right?

CF: Yes, yes, in fact…

BB: Tell us.

CF: Well, okay, trust allows us to argue, it allows us to debate ferociously, it allows us to really dig in with each other, rumble with… To use your language, it allows us to really rumble with whatever it is that we need to rumble with. And if we don’t have it, actually that calm veneer usually says to me that trust is not there, that’s a pretty good indicator that there’s a lack of trust.

BB: It is and a lot of people frame it as we have a nice problem. Like everyone’s so nice and like, is everyone nice or does no one trust each other.

CF: There’s a wonderful phrase from a book by Fernando Flores and Robert Solomon, they talk about cordial hypocrisy.

BB: Oh, I got goose bumps.

CF: Yeah, you see that.

BB: It’s so funny, the question we always ask is, “So, if you don’t talk to people when you’re frustrated or upset or you disagree, what do you do?” And the answer is, 100 times out of 100 in organizations, “We talk about them.”

CF: Yeah, yeah exactly.

BB: Cordial, what did you say, cordial?

CF: Cordial hypocrisy.

BB: Oh Lord have mercy, that’s hard.

CF: Yeah, yeah, I know that. The first time I read that one, “Wow, that’s so right on for so many places in so many situations that I’ve been in. But going back to your question just briefly about the trust that people are calm and so on, I remember reading… I think it’s in… Good to Great Jim Collins book. Maybe it’s in BE 2.0, I can’t remember, but he talks about the leaders in the good to great companies, the top team, talking about how they would talk about their team and their experience with their leadership team and how they loved each other. They loved working with each other, and they could have knock down drag-outs.

BB: That’s right.

CF: And that’s because there was trust, it allowed them to find the right answer.

BB: Yeah, just better performance, better decision making, better strategy, better culture because… Yeah. Okay, you are ready for the rapid fire?

CF: I think so. [chuckle]

BB: Okay, I think you’re ready. Okay, fill in the blank for me. Vulnerability is…

CF: Trust.

BB: Just sending big hearts to you. Okay, what is something that people often get wrong about you?

CF: I think they think I am wiser than I am.

BB: That’s so interesting. Okay. What is one piece of leadership advice that you’ve been given that’s so remarkable, you need to share it with us or so shitty, you need to warn us?

CF: [chuckle] It’s so remarkable. It’s pretty straightforward, but it’s… Make the environment, make the relationship, make the team safe enough so that people can fail and learn, and fail and learn, fail and learn. That’s the whole piece.

BB: God that’s good. Who is that?

CF: You know, I can’t remember, it was actually a woman that I worked for briefly… Gosh, it was a long time ago. So many years… [chuckle]

BB: To fail and learn, she knew psychological safety metrics before we talked about it.

CF: Exactly.

BB: Fail and learn.

CF: Exactly. She was presaging the whole learning organization concept. Shortly after I started working for her, she moved on and I moved into her position. She took a position in another company, so I… Sadly don’t even remember her name.

BB: Fail and learn, I love it. Okay, ready? What is a hard leadership lesson that you just have to keep learning over and over, the universe just keeps putting it in front of you?

CF: Yeah. [chuckle] Which one? Let’s see. [laughter] I think it’s really that the simple way to put it, I have to attend to my shadow, I have to attend to and dig into and recognize the shadow aspects. So for example, I keep having to learn this thing over and over again. Humility has the shadow of arrogance, and if I don’t recognize where I’m arrogant, I can’t be fully and honestly humble when I need to.

BB: Oh man, that shadow work is the work, isn’t it?

CF: It is yeah, absolutely.

BB: Yeah. What is one thing that you’re really excited about right now?

CF: [chuckle] Okay. So I’m starting a little trust blog with a colleague. We’re going to… Just the two of us are going to do this and we thought we’d try something different, rather than having guests, the two of us, both of whom are… Well, she is actually a Dare to Lead facilitator, so she has brings you a whole stream in so we’re going to take some different scenarios and talk them through from her experience, my experience, and put this out there as a blog. And I am really excited about this.

BB: Oh, I can’t wait.

CF: It’s Ila Edgar and she’s a Dare to Lead facilitator up in Canada.

BB: Okay, so when will it start?

CF: We are hoping to get it started mid-November, get it out, our first one out there in November.

BB: I love it. Alright, what’s one thing you’re deeply grateful for right now?

CF: [chuckle] You know I’m deeply grateful for my life, for everything that is. I’m loving this conversation, I’m so appreciative of you and all this first TED Talk that you did, from what happened then to where you are now, you’ve opened up this whole huge space around leadership, vulnerability, trust, and I’m grateful for you for doing that and pulling me into that and sharing this with me. It’s life being here.

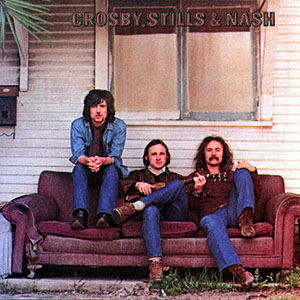

BB: Alright, this is going to be so interesting because we asked you for five songs you couldn’t live without so we could make a mini mixtape for Spotify. You gave us “For Emily, Whenever I May Find Her,” Simon and Garfunkel, “With A Little Help From My Friends” by Joe Cocker. “Suite: Judy Blue Eyes,” oh, so good by Crosby, Stills, and Nash, “O Magnum Mysterium” by Morten Lauridsen composer and the artist is the Nordic Chamber Choir. Powerful, I listened. And then “The Rose”… And you’re going to have to help me with the artist’s name.

CF: Oh, Ola Gjeilo.

BB: Ola Gjeilo, okay. In one sentence, what does this mini mixtape say about you?

CF: It says that in my next life, I want to come back as someone with some musical ability and talent.

BB: [laughter] Me too, maybe we’ll be on the road together.

CF: Yeah. I have none and maybe that’s because in my last life, I had it and squandered it and now my karma is that [chuckle] I was born with none. Can’t carry a tune, have no sense of rhythm, can’t remember lyrics. [chuckle]

BB: Oh yeah, I just make those up… Yeah, you just have to make those up. You have to join the Brené Brown club.

CF: What a good idea, I love it.

BB: Yeah, no, I just literally, I sing loud and proud and it’s never the right lyric. My sisters are always like “Jesus, Brené that’s… ” I’m like, “That’s alright, it rhymes in my head.” This was a wonderful discussion, I’m so grateful to you. The Thin Book of Trust, second edition, this is just a book every single person should have, whether you are in an organization, no matter what you’re doing, you’re a creative, it doesn’t matter… It is just solid, actionable, honest, and consumable in a flight.

CF: Yeah, thank you very much. And that’s exactly why I really am proud of it, is because it’s something that somebody can open up and start reading as they sit down in the plane in Los Angeles and be done by the time they get to Chicago and be able to use it in whatever they’re doing in Chicago.

BB: By the time they get to Chicago, they’re done with the book, and by the time they get their car or their Uber from O’Hare to their office, they can do something different.

CF: Yeah exactly.

BB: That makes the difference.

CF: Exactly, yeah.

BB: Thank you, Charles, so much for your work and for your time today.

CF: Thank you, Brené. Really appreciate it. It’s been a fun conversation, would love to do it again.

[music]

BB: I love this conversation. I’m going to admit things got a little dicey on… What was it, Barret? The clear complete… Whatever Brené’s not doing. It just, it was powerful to me, and I hope you got something from it. And you can find The Thin Book of Trust anywhere where you buy books, including our favorite independent bookstores. You can find Charles Feltman online at Insightcoaching.com, that would be the best link to find his blog, but we’ll push something out through social when the blog launches. He’s also on LinkedIn at Charles Feltman and on Facebook at Charles.Feltman. All the links will be on brenebrown.com where we keep all the episode pages for both Dare to Lead and for Unlocking Us. We really appreciate you being here with us on Spotify… We. I am looking at Barret right now. Barret and I appreciate you being here with us. Yes Barret?

Barrett Guillen: I do yes, thank you.

BB: [laughter] I was like we… “What, you got a mouse in your pocket Brené?” Yes, me, the mouse… I would never in a million years have a mouse in my pocket. I’d have a boa constrictor in my hand before I had a mouse in my pocket, let me just tell you all for sure. Thank you for being with us on Spotify and think more about trust. Dig into this book, read it with your team. We’re ordering it for our team here, it’s just… It’s incredible. Y’all stay awkward, brave, and kind, thank y’all.

BB: The Dare to Lead podcast is a Spotify original from Parcast, it’s hosted by me, Brené Brown. Produced by Max Cutler, Kristen Acevedo, Carleigh Madden, and Tristan McNeil and by Weird Lucy Productions. Sound design by Tristan McNeil and the music is by The Suffers.

[music]

© 2021 Brené Brown Education and Research Group, LLC. All rights reserved.