Brené Brown: Hi, everyone. I’m Brené Brown, and this is the Dare to Lead podcast. I am so excited to share this conversation with you. This is a deep-dive conversation with Jim Collins about his work, how it has absolutely shaped who I am as a person, as a leader, as a researcher. It has shaped my organization. So you get to hear me really ask all the questions that I’ve been saving up for probably over a decade. We talk about our values, our shadow values, which was an interesting question that Jim had for me, the power of curiosity, decades of grounded theory research on both of our parts, and we talk about the map, which is an integrated framework of 30 years of his research. We also talk about some of the amazing parables and stories and metaphors that have just captured the hearts and minds of his readers and really changed how we think about building organizations. The Hedgehog, the Flywheel, Level 5 Leadership. And this is a deep dive. This is one of our really long podcasts that you may have to listen to in chunks or… I really enjoy long conversations, so sometimes I just find myself walking really far. We’re going to talk about all of his books from Good to Great and Built to Last, to his new work, which is Beyond Entrepreneurship 2.0, an update to the original book.

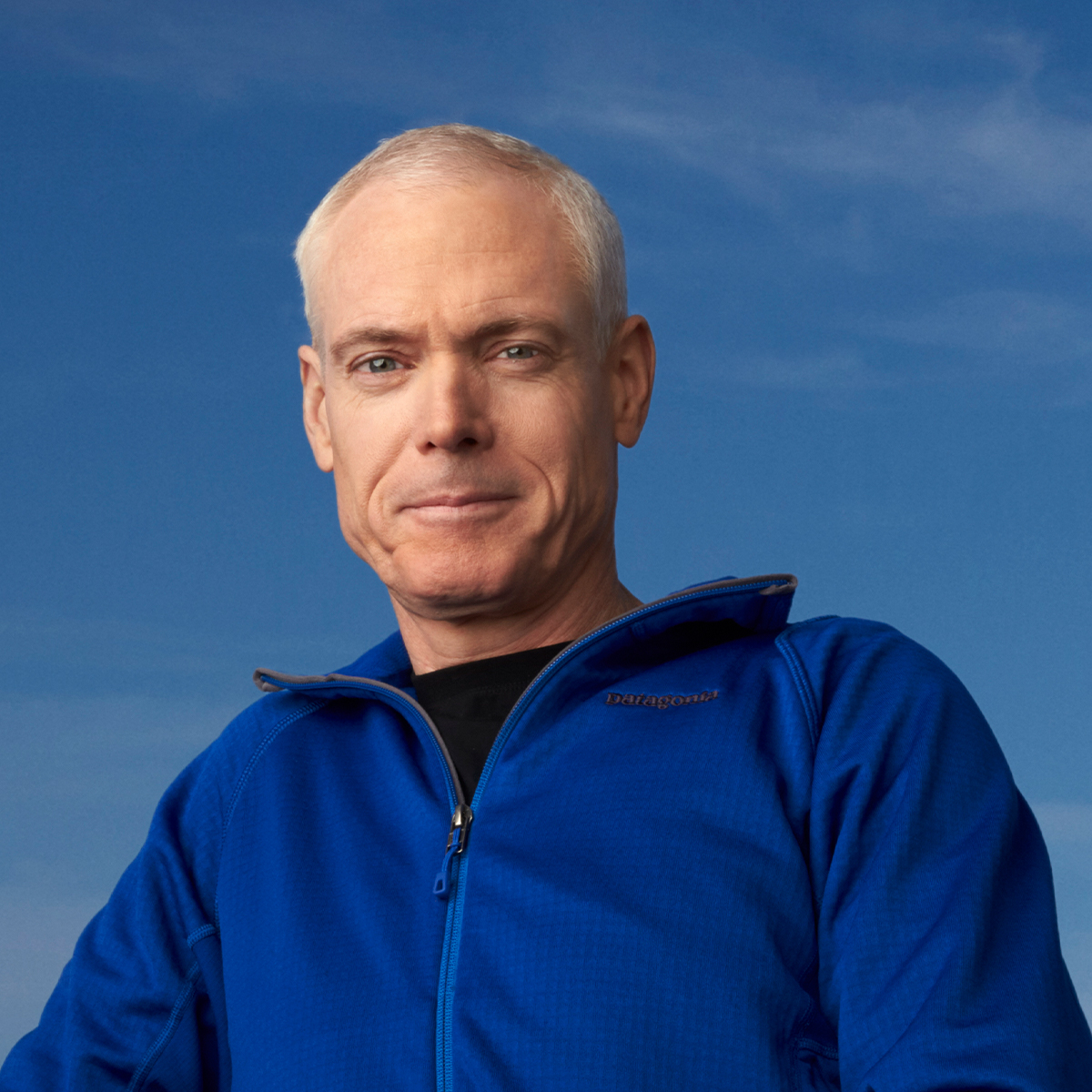

BB: The influence of his work on my life is hard to quantify, but I can tell you for sure he’s the reason you’re listening to me hosting a podcast right now. So before we get into the podcast, let me tell you a little bit about Jim, and then I want to tell you about some of the things we’re going to talk about today, because we talk about terms very quickly, and I want to make sure that everyone listening knows what the terms are before we get started. So let me tell you about Jim first. He is a student and a teacher of what makes companies tick, and a Socratic advisor to leaders in the business and social sectors. Having invested more than a quarter of a century in rigorous research, he has authored or co-authored a series of books that have sold, in total, more than 10 million copies worldwide. Let me just tell you, as a writer, you can’t even imagine what rarefied air that is. His books include Good to Great, which is the number one best seller. It examines why some companies make the leap and others don’t. Built to Last, which discovers why some companies remain visionary for generations. How the Mighty Fall, which delves into how once-great companies can self-destruct. Great by Choice, which uncovers the leadership behaviors for thriving in chaos and uncertainty. Note to self: 2020. And his newest publication is BE 2.0, Beyond Entrepreneurship 2.0.

BB: And in it, it returns Jim to his original focus on small entrepreneurial companies and really honors his co-author and mentor, the late Bill Lazier. I can’t wait for you to hear the conversation. So before we start… We go quickly, we just drop into some concepts that I know like the back of my hand because I’ve read about them, I’ve incorporated them, I’m living them, I’ve embedded them, but I want you to know about them before we start. So first, as you can see from the asset on social media, we talk about the Hedgehog. And let me just tell you, I have a hedgehog key chain, we have a hedgehog cookie jar at work. Jim explains the Hedgehog in several of his books. I came across it first in Good to Great. And let me tell you how he writes about it in the new book, in BE 2.0. He writes, “An ancient Greek parable says that the fox knows many things, but the hedgehog knows one big thing.” In Good to Great, he talks about how the fox tries to attack and kill the hedgehog. It’s cunning, it knows five or six different paths to take, it leaps, it crawls, it slithers, it jumps out of a tree. And all the hedgehog knows how to do is one thing: Roll up in a ball. But yet that one thing keeps the fox from accomplishing its goal every time.

BB: Jim writes, “Drawing upon this parable, philosopher Isaiah Berlin famously divided the world into two types of thinkers: Foxes and hedgehogs. Foxes embrace the inherent complexity of the world and pursue many ideas, never giving themselves over to a single pursuit or organizing idea. Hedgehogs, in contrast, gravitate towards simplicity, and think in terms of a single organizing idea that guides everything.” Jim continues, “Our research found that those who build great companies tend to be more hedgehog than fox. We also found that they implicitly or explicitly use a Hedgehog concept for disciplined decision-making. A Hedgehog concept is a simple concept that flows from deeply understanding the intersection of the following three circles.” So think about these three circles as a Venn diagram. “One, what are you deeply passionate about? Two, what can you be best at in the whole world? And three, what drives your economic engine the best?” So for me, when I say, “Oh, what’s my hedgehog?,” when we were thinking about doing a podcast, I was like, “Is the podcast a hedgehog for us? Are we super passionate about it? Can we do it better than anyone? At least in the area where I want to talk about, which is my work. And does it drive an economic engine?” And so the hedgehog became the litmus test for everything.

BB: Another concept that we talk about is called the Flywheel, and here’s how Jim writes about it, and he writes about it in Beyond Entrepreneurship 2.0, and he also writes about it in Chapter Eight of Good to Great. Jim writes, “Our research showed that no matter how dramatic the end result, building a great enterprise never happens in one fell swoop. There’s no single defining action, no grand program, no one killer innovation, no solitary lucky break, no miracle moment. Rather, the process resembles relentlessly pushing a giant, heavy flywheel, turn upon turn, building momentum until a point of breakthrough and beyond. Pushing with great effort, you get the flywheel to inch forward. You keep pushing and you get the flywheel to complete one entire turn. You don’t stop, you keep pushing. The flywheel moves a bit faster; two turns, four turns, eight. The flywheel builds momentum; 16, 32. Moving faster; 1,000, 10,000, 100,000. Then at some point, breakthrough. The flywheel flies forward with almost unstoppable momentum. Once you fully grasp how to create flywheel momentum in your particular circumstance and apply that understanding with creativity and discipline, you get the power of strategic compounding. Each turn builds upon previous work as you make a series of good decisions supremely well executed that compound one upon the other.”

BB: So that’s when we talk about the Flywheel in this podcast, that’s what we’re talking about. The last thing I want to just give you a brief primer on is we mention this term, “Level 5 Leadership”. And Jim has created a leadership hierarchy where level one is a highly capable individual, level two is a contributing team member, level three is a competent manager, level four is an effective leader, and level five is an executive who builds enduring greatness through a paradoxical blend of personal humility and professional will. So you’ll hear these terms that we talk about. I just wanted to share them with you. And you can dig into any of these either on his website, he has great like small white papers and an analysis of them. You can dig into them in BE 2.0, which is just… This book that we’re talking about, Beyond Entrepreneurship, Reed Hastings, the founder and CEO of Netflix reads it once a year, every year, just to stay aligned. So here it is, my conversation with Jim Collins. Enjoy.

BB: I just have to start here, Jim, I have to start with thank you. And I’m going to tell you why. I’m a very curious person, I love learning. I don’t think I’ve ever read a book that has not changed something in me, changed the way that I show up, or the way I feel or think about something. I can’t actually think of a book that hasn’t changed me in some way, even books that I don’t like or disagree with. But there’s a very small handful of books that didn’t change me, but shaped who I am today, and you are one of those people. I feel like if I do one of those at-home genealogy tests, you would show up in my DNA along with bell hooks, Marcus Borg, the spiritual writer, and probably the AA Big Book. You have shaped me in a very fundamental way, so I really have to start with a deep thank you.

Jim Collins: Well, I take that in, I really appreciate that. And as you know, since you are a deep researcher and really go deep into doing your work, you never know where your work is going to lead, and that it reaches people that you never know that it’s reached them. That’s the power of words, the power of idea, and I really appreciate that. I always believe that the currency of a teacher is really measured in the wonderful, wonderful students of whatever it is that you have to teach. So that’s a wonderful start. I appreciate that very much. Might, if it’s all right with you, I begin our conversation by turning the tables a little bit and engaging you with some of my curiosity.

BB: I think so, yes. [laughter] Yeah, let’s do it.

JC: One of the things I kind of spent a lot of, basically the last week just living with you and your voice, your ideas wrapped around my brain, and one of the things that I am very curious about is, can you identify the moment when you discovered vulnerability as the theme of your life’s work? And I ask the question for curiosity, but also as I’m doing new research now looking at the entire arc of people’s lives, which we may touch on at the end. One of the things I find is that there’s a very lucky few of us who early in our lives, we discover a life theme. And then life is basically, until we run out of breath, variations on a theme. And it strikes me, you found yours, and I’m curious if you know the moment when you realized that you had discovered that theme.

BB: I do know the moment, it’s a really hard moment in my life actually. I was at my mom’s house shortly after a terrible trauma in our family, where her only sibling, her younger brother, had been shot and killed. And my mom is just this incredibly strong, really raised us to be both tough and tender, to look pain in the eye. We were always the first family in with the casserole, we were always front row at the funeral. And my mom used to always say, “Don’t look away from other people’s pain because one day you’ll be in pain and you’ll want people to be able to look you in the eye so you know you’re not alone.” She came from a hard life. And so when my uncle was killed and I was at her house one day, it was one of the very few times I had seen her really sobbing. And I’m the oldest of four and everything that comes with that, and so I said, “I just don’t know what to do. I don’t know what to say. I don’t know what to do for you. I’ve never seen you… I’ve never seen you weak before.” And she wasn’t angry in her response, but she was very fortified and she came back and said, “This is not weakness, Brené. If I was a weak person, I’d be dead. This is vulnerability, and this is part of my strength, but this is vulnerability.” And everything that she was saying sounded very paradoxical to me and very confusing, but that was definitely the moment where I thought, “Yeah, I can never let this go until I figure this out.”

JC: And how old were you?

BB: Maybe 20… 25 or 26?

JC: Oh wow, yeah, okay. And so the seed got activated at that moment and then just gestated and continues now to push itself up above ground.

BB: Yeah, I think that’s right. And I think it was a combination of that and… The timeline’s fuzzy to me, but I either right then or right before was also working in residential treatment when I was getting my bachelor’s degree in social work. And that’s where I learned about the word shame. And so I think those two things together. We had had a young girl try to run away, and when that happens in a treatment facility where people are living, these are kids whose parental rights have been terminated, it goes on lock down, it’s just this terrible thing. And I remember the staff started acting kind of strange with the kids, and they pulled us into this emergency meeting and said, “We know you’re afraid, and we know for some of you who have not been through this before, it’s really scary, but you need to watch how you’re speaking to the kids. You cannot shame or belittle people into changing who they are.” And so I think it was just this culmination of challenges to feelings that I thought I understood.

JC: And kind of a related thing that began to ignite my curiosity as I was engaging with your work and your ideas and where it came from… So you and I are both Grounded Theory researchers, we are both deeply connected to an ongoing research process and love the discovery. And I think one of the reasons I love Grounded Theory is that it’s about hypothesis forming, it’s about discovery as opposed to proving. And so, we both share that. There’s an extra step though, and a lot of people do research, but I always look for what I think of somebody’s peculiar genius, I think of it as, a peculiar proclivity that is their spark of genius. And I would suggest that yours, the way it appears to me, is the ability to go from research to tools. That I was struck, in reading and learning, your capacity to translate research into tools, many tools. Tools, processes, methods, right? And you seem to do that, it’s almost facile, it’s almost like breathing. But I’m curious, how does that happen? What’s kind of the technique and the artistry of going from research to tool for you?

BB: [chuckle] I’m laughing, because that’s one of the questions I have for you. I see how this is going. Let me see if I can explain my process to you, but then will you talk about yours too? Because one of the things that I think has really moved me about your books is I know what to do when I am done reading. And so I think for me… No one ever asked me this question, so I have to think about how to articulate it. I think I reverse engineer what I learn. So I say to myself, “Okay, wow, this group of leaders has a tremendous capacity for transformation. They are transformational in their leadership. And they all talk about values, but that doesn’t help me help anybody.” And so then I start asking more questions.

BB: Then what I learn is just by asking them, I don’t say, “Jim, you’re a transformational leader, how do I teach people what you have?” Because a lot of times, as you know, Grounded Theory happens outside the awareness of the people who… The research participants who read my work, which is one way we validate it, are like, “Oh my God, that’s exactly right. I didn’t know that had a name.” And so what I will say is, “Okay, Jim, you seem to really talk a lot about the importance of your values. What are your values? How did you arrive at those? Oh, you only have one. Oh, you only have two. Why don’t you have 20? Are there not 20 things that are important to you?” And then I reverse engineer into finding out, “Oh, okay, so what we need to do with a group of people is help them identify one or two values out of a list of 100.” Because they have to pick the values where all the other behaviors and values are forged. There are… The people who are really doing this work and living into their values, do not have 20. It’s not like a Hallmark store. And so I think I’m constantly reverse engineering the questioning to get to, “How did you do this?”

JC: I’ll be happy to share my process of what I call Chaos to Concept here in a minute, but you provoked another spark of curiosity within me, and maybe we could just riff on it for a minute and then I’m happy to be shaped by your questions. You were talking about the values. And one of the things that is interesting, because I’m a very audio person, as we mentioned earlier as you and I were chatting, I was listening to Dare to Lead while I was driving and looking at Haystack Mountain here in North Boulder. One of the reasons I like audio books is because I like to be able to connect ideas to physically where I was when I heard that idea, which is how I remember them. So I will always associate these select two values with looking at Haystack Mountain on a beautiful December afternoon. So I started thinking about my two values. And when I worked with companies back when I used to challenge them on this stuff, one of the ways that I would always come at the values question is to say, “Suppose some researchers from another planet arrived and all they did was observe your actual behavior for a year chronically, like studying some sort of strange species. And then based upon your behaviors, they had to say these are the essential values, because behaviors would reflect the values in reality.”

JC: So as I was thinking about that, I thought to myself, “Okay, so what would I say my two, if I had to strip down to two?” And it’s quite clear to me what those two were. They are curiosity and relationships. I think anybody who knows me really well would not be cynical about those two. But then I started thinking of that question of like somebody observing you like a bug, right? What does the person value? And something struck me, which is that I think I have what I would call a shadow value. And a shadow value is one that if you really looked at your behavior and you were simply trying to impute the values based upon your behavior, there might also be a shadow value that you might not normally articulate, but it actually really is there. And for me, that shadow value, if I were to say there is one, is it’s a deep desire to have freedom in how I use my time. And if I look at a lot of the decisions I’ve made, the things I’ve chosen to do, to not do, how I’ve shaped my life, a lot of them have been guided by a real need to have creative freedom in how I use my time. So I was like, “Now, that’s interesting.” So it’s kind of like I had my two primaries, and then there was this shadow one that’s pretty strong. So my question for you on that is, do you think that the idea that there’s a shadow value has any merit? I’m only a data point of one. And do you think it’s fruitful to know what it is if you do?

BB: Oh my God, I could just geek out with you for days. This is the first seven-day podcast in history. I could really talk to you about this forever because what I’m wondering, I’m curious about, do you think we’ve hit on the difference between lived values and aspirational values?

JC: Well, it’s interesting because one of the constructs when we look in organizations, and you know people better than I do, I know organizations very deeply from my research. One of the things that Jerry Porras and I identified way back in Built to Last, is that any organization or institution keeps itself alive and vibrant by this dynamic of preserve the core and stimulate progress. And in the core are the values, and in the stimulate progress is change, improvement, innovation, renewal and so forth. But one of the key, key insights that Jerry really got us to see through our research in Built to Last is that people get confused on the difference between core values and practices, and that we have a lot of practices, and people often think the practices are the value. So you and I both know the academic world, there are people who might think academic tenure is a value. It’s not. It’s a sacred practice, but it’s not a value. The value is intellectual freedom of inquiry. And if at some point tenure were antithetical to that value, then we ought to be able to change the practice no matter how sacred it is in order to better protect the actual value. So separate the practices from the values.

JC: With this, I’m not sure that actually it sort of falls into that construct when I just think about my own case because I actually think that what we really value… I’ll just speak for myself. I can’t speak for thousands of people like you can. But when I really think about it, I have to really try to be honest with myself about, what is my actual behavior? If somebody chronicled all my decisions and why I made them, all my actions and why I did them in a really clinical objective way, and you can just look at the information, I’m highly confident that curiosity and relationships would be absolutely validated.

JC: I just kept thinking, “But you know, boy, there’s this other thing that just… I never wrote it on my own list of values, but it really does drive a lot of my decisions, or so many things I have chosen in my life to preserve that freedom of inquiry.” Now, it could tie back to curiosity, because what I really love is a freedom to explore what I’m interested in, what questions grab me around the throat and say, “I will not let go until you answer me,” which is kind of the driving force. So anyways, that was kind of my thought on that. And we could just sort of play with it. I’m happy to go wherever you would like to go, and if we have time, I have other questions, but they may weave in. It’s such a great chance for me to learn by our conversation. So I’m sure this will have a little bit of back and forth. Where would you love to go? What would you love to be curious about?

BB: No, I’m stuck on this now. This is fascinating to me, because let me tell you my N of 1 for me. So my two values are courage and faith.

JC: Yep. Do you mean faith in sort of a Stockdale Paradox kind of faith? Or do you mean faith…

BB: Yes.

JC: Okay, got it.

BB: As opposed to what other kind of faith? I mean as in believing in something I can’t see, believing in something greater than us, believing in the inextricable connection between human beings that can’t be seen, but is felt. Like that’s for me. And for me… Just more concretely for me, it’s God. Not for everybody, but for me. So I would say my shadow value… And it’s interesting because that’s a very Jungian way of looking at things, right? What’s the shadow? If I were observed by these aliens, here’s what I think the report would say about me, “Her values are courage and faith, which she is constantly having to deploy against her fear of losing control.” And so I would say my shadow value is control driven by fear probably, I guess. And so it’s just an interesting relationship to me around my values, what I hold to be the most important things about me, and the things I have to live into in order to be the person I want to be definitely are faith and courage. And it’s interesting because curiosity is the one that I’m always fighting about there, but I think a lot of times curiosity for me requires both courage and faith, and so I keep coming back to those. But the shadow value, the alien observation, is a really interesting question because I think I almost have to lean into my values to conquer what people would observe, which is control. Does that make sense to you?

JC: It does. What’s interesting about it is I could have also framed the thing about freedom to use my time as control of my time, right? In that sense, it’s a very similar one of I don’t want a lot of extraneous claims on my time, control of where I am or what I do, or what questions I pursue. So I can actually very much identify with that. And I also identify with something that you mentioned in… I can’t remember whether it was in one of the podcasts I listened to or whether it was in the book, it might have been in both. But this notion of there’s always this lurking fear that, “Well, in the end, it’s all going to go away anyway.” That sort of sense of the silent creep of impending doom. [laughter]

BB: Yeah, the foreboding, right, yeah.

JC: Exactly. It’s like this sort of dominant emotion of background dread. [laughter]

BB: Yes.

JC: Which I can laugh about, but doesn’t necessarily mean it’s not there. [chuckle]

BB: No. And so for me, with the time and the control, that really requires… I’ll just give you a concrete example. “Brené, can you do this for this non-profit?” And this is like, this is a domestic violence non-profit or something I really care about and have a long history of supporting. And I can’t because I’m doing this research that I really love, that I’m not honoring enough with my time. And so in that moment, if you were an alien watching me, you’d be like, “Man, she is freaking out about this pull, and the only way I get to know is through prayerful reflection that I’m allowed to say no and that doesn’t make me a selfish person, and then the actual courage to say, “I’m grateful that you asked, please ask again. It’s not going to work this year.” Let me ask you, just kind of riffing off this, do you have… And we do this in the work around values that we do from Dare to Lead, we talk about an indicator light that tells you you’re outside of your values. Do you have an indicator? What is your indicator light around, “Oh man, okay, Jim, you’re out of alignment here”? Do you have that?

JC: Well, I actually have a couple of things. I sort of think of it as warning tracks, guard rails, things that let you know if you’re veering out of the lane. But I’ve also got other things which I sort of describe as very proactive mechanisms for keeping me in the lane. So for example, maybe I’ll just chat about each of them for the moment, one for keeping myself in the lane, which I actually have installed a fair number of personal mechanisms for doing that. And when I was leaving Stanford and heading out on my own to, like you, be an entrepreneurial professor as opposed to a professor of Entrepreneurship, and I was worried, I was actually quite worried, that what would happen is that I would end up with so many claims on my time, but also wonderful opportunities that seven or eight or 10 years down the road, I would have not really pursued anything of great curiosity.

JC: I would have simply talked about or taught or whatever the work that I’ve previously done. And one of the things that I always wanted to do was to say, “You’ve got to go back to the well of really fundamental questions and work on them.” And I don’t know if you will relate to this, but I found this very interesting period of time before Built to Last was published, which is the double-edged sword of being unknown and anonymous. Now, the unknown and anonymous is, “Well, maybe nobody will ever read what you write,” and that’s distressing. But the other side is, there’s the bliss of the fact that nobody calls you.

BB: [chuckle] Yes, yes.

JC: Nobody’s asking you to do… You don’t have to spend time thinking, “How do I say no and preserve the relationship?,” because nobody’s asking you to say yes. So you can just work. And so when I was coming out of Stanford, I thought, “I really don’t want to lose the allegiance to the creative curious work.” And so I asked a number of professors who I admire, “How do professors you admire spend their time and remain really productive?” And I got this answer back, “50-30-20.” 50% of their time in new intellectual, creative, curiosity-driven work; 30% of their time in teaching; and 20% in just other stuff that needs to be done. And so I thought, “That sounds good.” So my first cut at that was to buy a stopwatch that had three counters on it, and I literally would switch through the day, whether I’m in creative mode, curiosity mode or teaching mode or in other mode, and I’d tabulate them up. And then that became cumbersome, I was trying to track it. And then finally I just simplified it down, and I keep a spreadsheet that I use every single day, I’ve done it for years now. And I open this spreadsheet at the end of every single day, and I put in that spreadsheet three things. The first thing I put down is the number of creative hours I got that day, so anything that’s driven by curiosity. Part of this conversation will count as creative hours because there are insights and creative things that are happening in my brain by virtue of our conversation.

BB: For sure. For me, too.

JC: So there are creative hours and that gets tabulated. The second thing that goes in is what happened during the day, a basic accounting of like, “These are the things that composed the day.” And the third is a score of how the day felt, totally subjective emotional. +2, +1, 0, -1, -2. And the reason I track that is because if you’re in a string of -2’s, it can feel like that defines your life, but if you have the data that, “No, actually, at the end of every day for the last two years, I’ve tracked this and the truth is that even if you have four or five -2’s in a row, I always come out of them.” The data shows it. This doesn’t define your life. And then I can begin to run correlations, what I call happiness correlations, between what’s happening in the days and what correlates with +2’s, what correlates with -2’s, so on and so forth. Now, the creative hours, I have a rule; I have to stay above 1,000 creative hours because it calculates about over the last 365 days, above a 1,000 creative hours every 365 day cycle.

JC: So what is today? December 3rd to December 3rd last year, June 15 to June 15 the year before. Every 365-day cycle, every single day, 365 days a year for 50 years has to be above 1,000 creative hours. I calculate it every single day. And so that is my way of saying, “I want to stay true to the curiosity, to the creativity, to that work, so I actually measure it day upon day upon day.” Now, I can have a zero day, that’s fine. But so long as the net is above 1,000, and that keeps my eyes on the road of around that really core, core driving value of stay true to the curiosity, and the learning, and the research, and the thinking. On the side of relationships, we have a thing here we call the Prime Directive, I guess picking up off of “Star Trek,” but the idea of the Prime Directive is anybody who approaches us, and as probably with you, the vast majority, have to get what we call a gracious decline, a no. We say no, but I always felt that the height of arrogance is to become successful and then act like it, and to not be grateful for the wonderful things that people would like to have you do. And you don’t want to hurt relationships, you want to build relationships.

BB: That’s right.

JC: We have a very clear mechanism here we call the Prime Directive, which is that… And you can’t really measure this, but you can certainly know if you got it wrong, or you might know if you got it wrong. No matter what answer somebody gets, and for most people it’s a no, they have to come away from the interaction with us and our team feeling a closer sense of connection to us and the work and the ideas, no matter what answer they get. And that is to us is, it doesn’t matter whether it’s a teacher with 15 students in a small school in South Carolina, or whether it’s the CEO of a Fortune 10 company, it’s relationships. And nothing is a transaction, everything has to go back to the idea that they walk away feeling better about having approached us than before they approached us. And we talk about it all the time, “How do we achieve the Prime Directive?” And then on the guardrail side, there’s… Obviously, if I’m starting to see those creative hours drop, then I know I’m starting to veer from really the central guidance of how I should be deploying myself. But the other is on relationships and the other values. I married really well, and Joanne and I just had our 40th Thanksgiving together.

BB: Congratulations, that’s a big deal.

JC: We got engaged four days after our first date. The person I most want to like and respect me in this world is Joanne, and Joanne is unbelievably perceptive and honest and fierce. And if I’m straying, I will hear about it. And your spouse knows you like no one else. Your spouse is the one who will know… If you are not living to your values, your spouse is going to know more than anyone else in the world. And so for me, if Joanne respects me and Joanne likes me… She will love me, but I want her to respect me and to like me ever more as the years go on. That’s the ultimate sign. And it’s the people in my life, those people like Bill Lazier, who we’ll probably talk about. It’s people like Jim Stockdale that I looked to, but it’s first and foremost, Joanne. And the one person I would never, ever want to let down is Joanne.

BB: I’m really… Man, I’m taking it all in because I think that is so true about our partners knowing the most. They are a brutal barometer. They know. There’s no hiding it, I don’t think. Have there been times in your career where Joanne has had to say to you, “Jim, too much. We can’t… This is not working”?

JC: One of the most marvelous things about a great life partner is they’re always giving guidance, input. Sometimes it could just be that I have to be reminded to make sure to close the cupboard doors because that’s what she reminds me, as the absent-minded professor. But there have been any number of times, or like even remaining true, because I value excellence for its own sake. And I remember I was working desperately on a chapter back when I was writing Great by Choice and with Morten Hansen, a dear friend and a great colleague. And there was this one chapter that was giving me trouble and I truly had suffered trying to get this chapter right. And I finally had thought I had finally got it, and I went in and I shared it with Joanne, my most honest and direct critic. And I was just wrung out, I had nothing left to give. I mean, nothing left to give. And she comes in and she just drops it on the desk, and she says, “I’m sorry, you have to do it again. It’s not there yet.” And I had to do it again. And she was right, there was something still down somewhere in my toes I could summon, and it could be better. And so those people in our lives, for me, I think the ultimate… If you pick really great people in your life, if you’re really lucky and you have great people in your life, and then those people are your ultimate mirror of when you’re falling short and when you’re doing okay.

BB: Is there an emotion that you experience? I’m asking because we do have guardrails put in and we kind of have systems in place, and we try different things all the time to protect creative time versus leading time and email time. And for me, one of the most dangerous indicator lights is resentment. Oh my God, when I am resentful, I do not like myself in resentment. I am not a good person in resentment. Is there an emotion or an experience that you have that tells you, “Man, I’ve got to reshape things,” or is it all kind of data-driven?

JC: Yeah, I think in the end, the data is extremely helpful on things, but… Yeah, it’s interesting, I learned something. I just want to maybe share this because I was thinking about it when I was reading your work. So one of the great mentors in my life, I’ve had many. I kind of created my own father, as you may know, because I didn’t really have one. And my dad was completely MIA and I had to figure out a way to have a father even though I didn’t really get one. And one of those mentors was Jerry Porras, who’s the one who really taught me how to do Grounded Theory research, and we invented the historical matched-pair method for what really then became the foundation for how I do all my research and my work. And Jerry, number one, just think about this, he was a massively tenured senior dean when I was 30 or 31 and we started working together. And when it came time to publish Built to Last, just think about this, when it came down to publish Built to Last, he never even raised the question, he just said, “Yeah, we should put the names on alphabetical.”

BB: You’re kidding.

JC: Yeah. It was Collins and Porras. But just the sheer sense of generosity, and he was a great Level 5 mentor, he really was. Those are the kinds of people I found in my life. Well, Jerry co-created a course at Stanford called Business 374, that is, actually the nickname of it is touchy-feely. And what you do in this course… And there’s a lot of sort of analytic math types like me that might end up in this course, or at least we should end up in the course, I would think. And you spend 10 weeks with 11 other people, and the only thing you’re allowed to voice for any time that you’re in that class is your feelings in T-groups. This was very hard for me, I was young when I went through it. But the lesson that I took away that Jerry taught me on that, and the more I live with it, the more I really believe it is true, is that even for those of us who are data-driven… And I am. I’m data-driven, I love research, all that. But we do not fundamentally operate at the level of thoughts and analysis. We fundamentally operate at the level of feelings.

BB: Oh my God, that’s so… Can you say that again?

JC: We do not fundamentally operate at the level of thoughts and analysis. We fundamentally operate at the level of feelings. And that’s one of the big things I learned from Jerry. And that you see any human interaction and somebody says, “Well, I think we should do this,” or, “I think we should do that,” or, “This is all messed up,” or whatever. And Jerry says, “You know, you’ve got all those things that are true and they’re factual and they’re all these, but the real conversation is what’s really happening at a feeling level.” And although I would say that I’m not super great at reading that the way Jerry was, I think his fundamental insight is right. So when you asked “Do I just go to the data?,” it’s interesting, even that thing of the +2, +1, 0, -1, -2, what I’m really trying to calibrate there is the totally subjective sense of the feelings of the day. The quality of your day isn’t in what you think of the day, it’s how you feel about the day, how you felt. So I’d have to think about that, do I have a single… I mean, I can notice certain triggers.

JC: I think a big one for me is something I have to always fight against is regret of things that I had either done or not done, that just seep back in, and I will wake up at 5:00 in the morning and they’ll seep in. You can picture this black mist coming in and boom, all of a sudden I’m back to something that I regret, and then that just begins to poison everything. And so that’s why I use the 20-minute rule at night, which is that if I wake up and I’m not back to sleep by 20 minutes, I get up, no matter what, and I go downstairs and I go into pointing forward, new research, new writing preparation, rather than looking backward. Because if I’m laying there in bed at 4 o’clock in the morning and those regrets come in, I just go backward, backward, backward, and then I just begin to feel worse and worse and worse about myself, which is a very bad start to the day. [chuckle]

BB: Yeah, no, it’s debilitating. Right?

JC: Yeah, yeah. And I think we’re all prone. One of my mentors, Michael Ray, had a wonderful line, which is, “Comparison is the primary sin of modern life.” And certainly if I feel myself making negative comparisons of myself to others or to a standard that I just think is the right standard, that can be sort of the start of a doom move.

BB: That reminds me very much of Theodore Roosevelt.

JC: “It is not the critic who counts.”

BB: That, and “Comparison is the thief of joy.” I mean, it’s so true. Okay.

JC: [inaudible] [laughter]

BB: Yeah, no, I love this, I love this.

JC: I knew that you would just have so much fun. Think of it as… My mascot has always been Curious George, and I always love the image. If you go to my bio on my website, you’ll even see a chimp climbing up my bio.

BB: [laughter] Oh my God, I thought I had a virus on my computer.

JC: Yeah, no, no. You saw the chimp?

BB: Yes, climbing up the text of your bio. [laughter] I called my sister in, and I was like… She works as my chief of staff. And I was like, “I’ve got a monkey virus.”

JC: No, no, that’s there on purpose because the bio’s got sort of these professional things and all this stuff on it, and I’m like, “But I am fundamentally a curious chimp. We’re going to put an animated chimp climbing up my bio.” So I picture like the CEO of a major company in China going there, and all of sudden there’s this bio and then there’s this chimp climbing up. That’s an expression of the curiosity value. It’s supposed to be fun. There should be a chimp on my bio just because it’s just… Who else would do that? And so we have a thing around here we call “chimposiums,” and so you and I just had our first chimposium.

BB: Oh my God, I love it. And I like you even more because of that little chimp crawling up your really stacked, serious CV made it so fun. Of course, I thought I was like, “Oh my God, I’ve been invaded. I don’t know what’s happening.” [chuckle] Okay, now, if you could see in my office right now, you would see your books sitting on top a very large hedgehog cookie jar. Two things. The Hedgehog changed my organization, and the Stockdale Paradox changed my life. Can you walk us through the Hedgehog and how you got there and why you have to admit that it is globally remarkable?

JC: So we were talking earlier about your kind of strange facility for tools, right? And you were asking about how I do, from the research to what ends up in someone like the Hedgehog or ends up in the Stockdale Paradox or ends up in Level 5 Leadership. So first of all, there always has to be a research method. Ours is a historical… I really loved how you had Jon Meacham on and his power of history. I’ve always believed in history. And so when Jerry and I came up with the matched-pair method where we were going to look at companies that became great in contrast to those that didn’t, I said, “We need to be historians.” And so my contribution to the method was to say, “We need to study history.” You don’t want to look backwards at Intel in 1972 and look at the decisions they made, you want to try to put yourself in 1972 and think about, “How did the world look to them at that point? How did the world look to their comparison company at that point?” And then you phase shift to 1973, ’74, ’75 and so forth. So that kind of historical lens, that’s then comparative as you go along. So people often think I’m a business author, and I’m not.

JC: I’m interested in really deep human questions. And it so happens that this methodology is where the data is, that you can take publicly traded companies, you can get tons and tons of data that’s sort of more or less consistent across companies of different types, and then you can really track them over time. And using that rigorous comparative method, because industries give you pairs, you can have Intel and an AMD, you can have a Boeing and a McDonald Douglas, and you can track them over time and compare and contrast how they made decisions. And using all that data and information, you can begin to get insights. You can also use pre and post. So Good to Great, you’ve got the era of a company in a mediocrity phase and an era when they’re in a great phase, and you can say, “What changed? What was different between this era and that era?” And then their comparison company, “What didn’t they do as a result or what did they do that was opposite that didn’t lead to that inflection?” So there’s this years and years of careful selection of the cases, careful study of the historical collection, the quantitative, the qualitative, all of that adding up.

JC: And what happens is, you begin to try to make sense of it. And so there’s a constant looping and iterative process where you’re beginning to try to see what concepts explain or at least correlate strongly with the difference between the great era to the mediocrity era, whether it be a great company to a mediocre company, or a good to great company across time. And you’re using this to say, “What was different?” And then based upon those differences, “What ideas are behind that? What concepts or principles might drive and explain that difference?” Now, as you begin to do that, one of the things that struck me early in my intellectual journey is there are different kinds of conceptual vessels. And the first question is, “What is the conceptual vessel for an insight?”

JC: So once you’re confident that an insight might actually stand, you need a conceptual vessel. Now, what do I mean by a conceptual vessel? Think about you can have a hierarchy: Level one, level two, level three. You can have a stage process: Stage one, stage two, stage three, stage four. You can have a dialectic: Stockdale Paradox or preserve the core/stimulate progress, thesis/antithesis/synthesis ideas. You can have an overlap, a Venn diagram type of idea. Or you can have a connectal causality, you can have an equation. You can even have something that’s a sentence but that captures an essential underlying idea. So like “Multiply, vary, let the strongest live and the weakest die,” which was Darwin’s seminal insight, I think on page 157 of Origin of Species. And so I always stop and then ask, “What’s the conceptual vessel?” So if we take the concepts that you were just talking about, if you take the Hedgehog… Let’s take that one.

JC: So what we found is that you have this process of leaders getting the right people, disciplined people who engage in disciplined thought and then they take disciplined action. And what we noticed is that it’s not like they kind of said, “We need to go from good to great. Oh, let’s go off and spend two days and what we’re going to do is we’re going to have great insights, and we’re going to know what we should do, and then we’re just going to come out and do it.” It really didn’t happen like that. Rather, what it was is they were kind of making a series of iterative decisions in kind of a council format that you read about in Good to Great. You make decisions, you see how they worked out, that adjusts your clarity and your understanding. And I kind of describe it as that it was like they were walking through the woods in the mist, and they’re bumping into trees and it’s really misty. But eventually the fog starts to clear and then one day they can see really clearly and they can go really fast, but it takes time to get there. And so then I started thinking through, “Well, let’s start putting patterns on how is it that they began to get better and better at their decisions. What are the things they were thinking about?” And so you begin to take hundreds of events, decision events, and you begin to sort of start coding those decision events. Like “What were the things they were thinking about in this and these ones that were better than other decisions and so forth?”

JC: And you began to notice, well, this decision had these elements to it. Like they just weren’t very interested in electronic watches, they had no passion for that. Okay, so that’s interesting. And this one just didn’t make any money. And this one they were like, “Well, we can never really be super great at that, we can’t be better than anyone else at that, we shouldn’t be doing that.” And you begin to notice this and you do this across hundreds of decision events across all of the study set and eventually picture a table, and on that table are lots of slips of paper. Each slip of paper represents a decision event that, this comes from the research, and you begin to think of it, and all of a sudden you begin to realize what this is, is this is a Venn diagram concept, and that as they got more and more clear, they more and more began to make decisions that met three tests. They were deciding to do things that really reflected what they were really passionate about, which included what they held deeply in their values, what they really felt their sense of purpose was, and just what they sheer loved.

JC: But they also then had this other piece, which was a real rigor around the question of, “Could we really be the best at that? Because if we can’t be the best at it, then we’ll never be great at it.” And then the third was really smarts on their economics. They really began to understand what drove their economic engine, truly drove their economic engine. And then once they got clear, then you begin to see this bubble out, and all of a sudden you could begin to see the Venn diagram or the Hedgehog concept emerge, which is those three circles. The intersection, making all your decisions, so they go in the middle of those circles that fit what you’re passionate about, what you can and cannot be the best in the world at, and what truly drives your economic engine. That’s sort of the chaos of the data to a concept. But then there’s this last step, which is wrapping paper, and this I learned from Joanne. Joanne, when she was a graduate student, made this great contribution to me. She went off and she did a whole study on ideas and power of ideas. And one of the things she observed was that if you can wrap an idea in a way that if I give you that idea as a present, it’s wrapped, and you have to unwrap the idea and then understand it and then re-wrap the idea and now it’s yours.

JC: So what I really began to notice was that as they got clear, it usually simplified down to one really simple thing that they could focus their energies on. And I kept thinking about that Isaiah Berlin essay, “The Hedgehog and The Fox.” The hedgehog knows one big thing, the fox knows many things. And then I realized, “These people were pushing towards what they needed for their organization something to be hedgehog about, that just all roads lead to Rome, would come back to this hedgehog.” And so it wasn’t the three circles, it was… It’s the Hedgehog Concept. And so it was that wrapping paper. So if I say, “Do you have a strategy?” “Oh yeah, everybody knows that we have a strategy.” It’s like, “Do you have a Hedgehog Concept?” You have to pause, and now what you have to do is say, “Well, what’s a Hedgehog Concept?” Now you have to open it up.

JC: And it’s not a cutesy thing, it’s like there’s a reason. What’s the big thing? And the big thing has three components to it, and we need to make decisions that fit with that, and if we do that in a disciplined way, we’ll begin to build momentum, which will then lead to the Flywheel. And so we see how all this comes together, is from question to research method, to data, to chaos, to insights, to emerging validation of those insights, to conceptual vessel, to a construct, to wrapping paper that then ultimately fits in a whole overall framework. So if you were kind of to think about the essence of what I do, that’s it right there, and that’s how the Hedgehog came to be.

BB: It’s really weird, I just have to tell you, Jim, to hear someone… Barrett from my team is in the office with me right now and she’s hearing the conversation and she’s looking at me like, “Oh my God.” It’s very weird to hear another Grounded Theorist put this out in a way that you know when you hear your work described accurately. Barney Glaser, who Glaser and Strauss developed Grounded Theory at the University of Chicago, ’30s, ’40s. He was at UCSF and he was my methodologist on my dissertation, and he didn’t use the word chaos, but he kept warning me, “It’s a drugless trip.”

JC: [laughter] Meaning you don’t get to take any drugs?

BB: Yeah, exactly. And I was like, “Well, what do you mean?” And he said, “There’s going to be something that feels out of control.” And it was really hard because I was in a PhD program that had never had a qualitative dissertation before, and so I had to get special dispensation from the provost and all this stuff to do this qualitative dissertation. I think they just let me do it because Barney Glaser was my methodologist. And the Sociology Department really lobbied for me. They’re like, “This is a big deal, this is a big methodologist person.” But I remember at a point saying, “I don’t understand what’s happening anymore. I’ve lost control of this.” And it felt so chaotic. And to hear you say from chaos to concept, and Barney would always push me and say, “What is the core thing here that explains the chaos? What is the main concept that explains the chaos?” It’s a weird process, do you not think? That combined with… You know, for those of you who are not Grounded Theory methodologists, the Constant Comparative Method, which it sounds like you use that as well, is that true?

JC: Absolutely. It’s cornerstone to… If you just studied a bunch of successful companies, you’d find that, guess what, they all have buildings and their chief executives wear clothes. And so if I came to you and I said, “You know, if you wear clothes and you work in a building, you’re going to be a great company,” it’d be absurd. So you find all the comparisons. Also, they wear clothes and, well, until the pandemic, work in buildings. And so yeah, there has to be comparative. You always have to say, “Not what did the great companies in their best years share in common?” It’s, “How were their whole approaches different than others that were in the same situation that didn’t do as well?”

BB: I remember one time Barney gave me this book of Grounded Theory dissertations that he had published himself. And he said, “One of the things about Grounded Theory that’s so powerful is that when you… ” To Joanne’s point, “When you wrap something up in something memorable and sticky that people can unwrap and re-wrap and embed and make their own… ” One of the compliments I get a lot about my work that people outside of research think it’s an insult when people say this. They’re always like, “Oh my God, I can’t believe she said that to you.” But people will say, “I knew everything you were talking about today, but I didn’t know there were words for it. I didn’t know it was a thing.” And so how did you get so good at wrapping? You’re like “Elf.” I’m thinking about “Elf,” the movie when Will Ferrell’s wrapping all those gifts. You’re an Elf-level wrapper. How do you go to type of vessel to, “Am I going to use a metaphor, a story, a picture?”

JC: Yeah. So remind me, I might want to pop back in a minute to the Hedgehog because there’s one thing that I’d love to share with your student body, your listeners, about the power of the Hedgehog at an individual level. Let me just hit that real quick, and then I’ll go to this kind of magic moment that happened. So I’ve actually, with a lot of the ideas in our research… And I mentioned earlier I don’t think of myself as a business author. It’s like people thought that Peter Drucker was a business author, and he wasn’t. And Peter had a big impact on me, and what I came to understand is that Peter was ultimately interested in a giant human question, which is, “How do you make society both more productive and more humane?” It’s this beautiful, big question, and I’ve always been interested in sort of the big questions. And the research through rigorous data and companies allowed me to look at larger questions. And as a result, Good to Great is not in my mind a business book, it’s a book that developed powerful ideas that came from studying businesses in this rigorous way.

JC: So the Hedgehog, very powerful for companies, very powerful for non-profits, but think about it at an individual level, as a human idea. “What’s your hedgehog?” I like to ask people. And think about it as that, again, it’s the three circles, but it’s slightly different. It still starts at the top circle, which is, “What are you really passionate about and love to do?” But you know that old saying, “Do what you love, the money will follow”? Well, that’s not true. I love to rock climb, and no one’s ever given me a check to go rock climbing. And then there’s the second circle, which is it’s not about best in the world, because if you’ve limited every person should only do what they can be best in the world at, there would only be one orthopedic surgeon because only one can be the best. The second circle is this, “What are you encoded for? What are you made for such that when you do it, it’s not that you’re good at it, it’s that you’re wired for it?”

BB: Oh my God.

JC: In my case, I thought I was going to be a mathematician, and I went off to college and majored in mathematical sciences. But while I was there, I met the people who are encoded for math. I’d get to the same end of the proof, but they did it in one-third the number of steps and one-third the amount of time. Their brains were made for pure math. My brain was not made for pure math. I was good at math, but I wasn’t encoded for math, so that couldn’t be my hedgehog even though I was good at it, but I could never be wired for it the way they are. And the key is to discover what you’re wired for. Then the third is, and you can make a living at it. You can make a living pursuing the goals that you find meaningful. And if you have all three of those, I wake up in the morning, “I’m really passionate about this, I’m wired for it. I’m encoded for this. And I can actually do something useful for which there’s an economic engine.” You found a hedgehog.

JC: And one of the things I think about what makes a really humane company that’s also incredibly productive is the greater the probability that any random sample of people in your company are in seats on the bus that align with their personal hedgehog. So they’re in a seat that, “I love doing this. I’m really wired for this. I’m good at this. I’m made for this.” And they’re also doing something useful enough that the company can pay them for it. And you have more people where they are in their hedgehog in their seats, you have this marvelous genius of the end of it’s a humane thing because they’re in the right seat, and it’s a productive thing because they’re in their hedgehog in that seat. Anyways, forgive me for going off on the personal hedgehog there.

BB: No, it’s amazing.

JC: For young people, I always like to say that a really good place to get to is to have discovered your hedgehog before you’re 30, if you can.

BB: Oh man, I’ve just got to tell you that I am just seeing a little hedgehog bus full of hedgehogs, and it just… I’ve got to tell you, you’re going to read my bio on my website next week, and it’s going to have a little hedgehog climbing up the side of it.

[laughter]

JC: Yeah, I don’t know how to answer your other question because there’s this mystery moment when something just flashes and I don’t remember when it became clear, the Flywheel analogy, the linking to the Hedgehog. I do remember when BHAG happened. A lot of times what happens is this: I’m trying to teach, and I’m trying to help somebody understand something, and it pops out of my mouth. I see it on the table, and then I grab it and put it in a cage before it can run away.

BB: Oh my God, yes, I’ve got both hands up in like a prayer yes. Okay, so I’ve got to say two things really quick. So I want to go back to the Hedgehog for a second. So for me, I had to figure out my personal Hedgehog before I could figure out this organization’s Hedgehog. And one of the things I have to say that the irreversible leap…

JC: Yes, Bill Lazier.

BB: So Bill said, “Take that irreversible leap and it’s a scary thing.” Let’s see if you track this, this is kind of a crazy thought, but it’s where I am. We did your book as a organization-wide read, but I felt like the moment I said to everyone, “We’re going to get hedgehog-y.” We got hedgehog stationary. We embodied this thing. To me, it was an irreversible leap because I’m surrounded by people that are way smarter than I am. And when I said, “This is the litmus test we’re going to use,” I got held accountable in the most freaking painful ways as the founder and the CEO of this organization, because I got challenged on whim-y ideas. That people would start saying, “How does this fit our hedgehog? I don’t understand. We’re not actually really that passionate about it, we’re not even mediocre at it, and… ”

JC: [chuckle] “And we’re going to lose money.”

BB: “And we’re going to lose money.” And then I would say, “Well, I think I’ve worked my ass off for the last 25 years, so if I want to try this… ” And they’re like, “That’s fine, but let’s not call it a Hedgehog.” But man, was that… Just learning about the Hedgehog is an irreversible leap.

JC: And of course, you have a capability that I am less wired for, which is building, leading, and running an organization. I would say that that’s not heavily in my Hedgehog. And so you’ve had to really think about translating it to the company. I’m not convinced that in life hedgehogs are always better than foxes. I think I’m maybe a serial hedgehog is maybe the way I think of myself, but there are walks of life where being a fox is very helpful and there are certain fields were knowing a lot of things… Like if you’re a neurobiologist, you want to really understand the biology of human behavior. I just took a whole course on this. And you have to be pretty fox-like about everything, from evolution to the way synapses fire. You’ve got to have a lot of fox understanding to really understand the big thing. I think the power of the hedgehog is something you just put your finger on, which is organizations need focus in order to really get that traction of that sort of flywheel momentum, a series of good decisions that accumulate one upon another over a long period of time, building momentum like a flywheel.

JC: And part of how you do that is to say, “Look, folks, there are lots of things we could do, but this is the big thing, and we remain focused on the big thing so that we can get that cumulative momentum.” Sometimes a fox-like leader still has to have a hedgehog for the organization in order for the organization to have momentum. And then you can experiment around the edges. In Great by Choice, I write about fire bullets and then fire cannonballs; you can fire bullets and find things that will work. And every once a while, you find that something new that you hadn’t done before actually still meets the three tests, but you didn’t know that and you fired a bullet and it worked. So for example, if you think about the evolution of, say, Apple… Or actually, here’s one way back in history, but it’s interesting. If you realize that for the first maybe couple few decades of Marriott’s life, they didn’t have hotels, they were restaurants and started with a single A&W root beer stand. And then J. Willard Marriott Junior tried an experiment of doing a hotel, and it worked. And then it turned out that the passion circle for them was, “Actually what we’re really about, what we really love, is helping people away from home feel they’re among friends and really wanted.”

BB: Hospitality.

JC: Exactly. “And we can do that in restaurants, but guess what? I’ve proven with our first hotel we might be able to do this in hotels too.” So what happened is through experimentation and rigorous empirical validation, you can expand the number of things that meet all three tests, so that that’s what allows you to evolve and extend the flywheel further and the hedgehog kind of grows, if you will, but while also still having the discipline to say, “No matter what we do experimentally, if in the end it doesn’t meet the test, we’re not passionate about it, we can’t be the best in the world at it, and there’s no economic engine in it, it misses any one of those three tests, it might have been a fun experiment, but it shouldn’t be converted into a really big cannonball for what to do next.”

BB: I want to hover over something that you just said quickly there because it’s a really profound thing for me, is start with bullets before you move to cannon balls. Because I’m not only am I like, “We’re going to try this and I’m going to force it into a hedgehog-ness, but I’m starting with all the gun powder in one cannonball.” But I’ve learned, you’ve taught me. So do you want to just unpack that real quickly for people that were listening to the start with bullets and then just the calibration process? Because I think it’s so fantastic.

JC: Yeah. So let’s just kind of stand back, and this kind of really marries Good to Great and Great by Choice, which are two books that sit next to each other. Great by Choice I did with my colleague, Morten Hansen. I’ve had these wonderful people in my life; Bill Lazier and Jerry Porras and Morten Hansen and these wonderful collaborators. And Morten and I did Great by Choice. And let me just kind of lead into it by essentially laying out the arc of how a company goes from good to great and stays there. And let me just very quickly hit that and then tie this bullets and cannonballs in, because it’s really a cool thing. So it basically starts with the right people, and we can spend whatever time you want on that, the right people led by these Level 5 leaders who are humility and well, for the company, not themselves. And that’s just all about just one people. Then you begin to take discipline thought, which involves embracing an “and” view of the world, the genius of the and, the Stockdale Paradox, which you mentioned earlier, which we’ll probably touch upon in this pandemic world, and then you get your hedgehog, and the discipline thought to really understand the hedgehog. Then you begin to make a series of good decisions that fit with that hedgehog and execute them really well. And that moves you into disciplined action.

JC: And then disciplined action, when you begin to make those hedgehog-like decisions and execute them really well, you begin to build momentum, and this is the Flywheel effect where you begin to… It’s like it’s not just one turn, two turns. It’s two turns turn to four, like pushing a giant, heavy flywheel. Then six and eight and 10 and 12 and 100, and 100,000 and a million turns. That flywheel builds all this momentum by those decisions that fit with the hedgehog, adding up one upon another over time, and at some point you hit breakthrough. So that’s in disciplined action. Then what we learn in Great by Choice is there’s a couple of ways that you really accelerate the flywheel. One is with the execution power, the 20 Mile March, which is basically doing a few things really, really well, always. But then there’s this bullets and cannonballs. So how do you renew and extend a hedgehog, renew and extend a flywheel in a world that’s changing while also remaining true to what really fits in those three circles?

JC: And so imagine you have a ship bearing down on you and you have a certain amount of gunpowder, and one approach would be, “I’m going to take all my gun powder, I’m going to put it in a single cannonball, and I’m going to fire at that ship and hope hits.” And it goes sailing out there and it splashes in the water. And you turn and you look back and you’re out of gunpowder, and here comes a ship and you’re in trouble. But suppose instead what you did was you took a little bit of gun powder and put it in a bullet, you took your best shot with that bullet, it sails out there, it misses, but you see it’s 30 degrees off, so you take another bullet, you recalibrate, fire again. Now you’re 10 degrees off, take another bullet and fire, ping, you hit the side of the ship. Now you take your gun powder because you know it’s a calibrated line of sight, now you take your gun powder, now you put it in the cannonball, and now you fire the cannonball out to the ship and hit the ship.

JC: Now, what we found for entrepreneurs who then go on and build very successful companies in highly turbulent environments, which is most of our world these days, is they’re very disciplined about fire bullets then fire cannonballs, both as a hedge against the world’s uncertain, what we did before might not work in the future, and to find new things that might work, and to do this in a very disciplined, calibrated, empirical way. But at some point they fire the cannonball once they have calibration. Now, here’s the key point. What gets very exciting is then through that process of firing bullets and you got your people, you’ve got your Level 5 leaders, you’re confronting the facts, you’re living the Stockdale Paradox, and you got the Hedgehog and you’re making decisions, and that flywheel’s building momentum, and it’s really going, and you’re executing on it really well, and you’re 20 mile marching. And then at some point, like, how far can it go? Well, there’s this marvelous moment of if you look at great companies in their history where they make some kind of a beautiful extension of the Hedgehog and the Flywheel.

JC: So take Apple. For most of its history, it was a personal computer company, right? And then when Steve Jobs comes back in ’97, he gets the right people and all that, but then he begins firing some bullets, one of which was this little bullet called the iPod. It was not a cannonball, it was truly just a bullet. It was such a bullet that it only merited a single sentence in the 10-K the year that they put it out. It was just called, “A natural extension of our digital hub strategy.” It was a bullet, but a very cool bullet. And it turned out that a whole bunch of people inside Apple kind of wanted to carry their music around like that, and then they wanted software to be able to organize, and that led to iTunes. And then came this thing about, “Well, maybe we could put it on Windows machines, and so forth.” You can see it was bullet, bullet, bullet, and then it was like, “You know, we don’t have to be just a personal computer company. We could be like this personal device company with everything that’s happening.”

JC: And once they fired the cannonball, the natural extension went beyond the Macintosh and all those computers. You had this big burst of momentum in the flywheel, and now you then added the iPod and the iPhone and the iPad and all that, which were extensions that continue to this day. And so notice how what you have is you’re sort of doing all the things and you’re in the hedgehog, but you don’t say, “The Macintosh computer is our hedgehog. Our hedgehog is what we can be passionate about, best in the world at, drives our economic engine. And if by bullets and cannonballs we discover an extension of that that merits a cannonball, let’s do iPods and iPhones, it could then take us to a whole other place, but still consistent with that idea.” And you look over history, that’s exactly what you see over time.

BB: I’m looking at the new book, BE 2.0, so the Beyond Entrepreneurship, your second edition. Is the map on 150 or something?

JC: Yeah, Chapter Six. And the beauty of the map is, if I died tomorrow, which I don’t intend to, I’m only 62, I describe as mid-point in my career, but if I died tomorrow, I would just say to people, entrepreneurs who want to build a great company, “Read BE 2.0 and follow the map.” And the map is 30 years of work. Chapter Six. I took 30 years of research, all the studies, which I sort of thought of as ultimately it wasn’t just a bunch of studies, it’s actually been one giant study into what makes great companies tick that came out in installments. Built to Last, Good to Great, How the Mighty Fall, etcetera. But then I wanted to create a single cohesive framework that would take the 30 years of research and put it in one place where I could say to people, “This is how what the map came to be, but here is the map.” Brené, if you said to me, “Jim, I want what we’re doing to be an enduring great company,” I’d say, “Read BE 2.0 and follow this map.” It starts with you as a Level 5 leader and then building new Level 5 unit leaders. And then we go to the whole people question. Then you can see how this whole map… And now notice, we just went through up through stage three of four stages right there in the map.

JC: Then you get to the building it to last and staying alive, and the productive paranoia, and managing your dread, and becoming a clock builder, and the long-term preserve the course/stimulate progress, and all these things. But the beauty of it is there now is a map. And as a researcher, I’m sure you… This is the thing, when you talk about the chaos to concept. For me, one form of bliss, I’m sitting here in my management lab and literally, I have the map laid out on a single whiteboard right to my left, I’m pointing at it right now. One of my goals in life was to finally be able to take three decades of work and fit everything integrated and connected into one map. And that’s what this is. And now I’m like, “Okay, I’m moving on to new questions outside of the ones I’ve worked on. The what makes great companies tick map is there, I can look at it on the whiteboard, it’s a single whiteboard. And it’s just deeply satisfying, intellectually satisfying, to look at it and say, “I didn’t know it would take 30 years, but there it is. I can exhale and I can move on to the second half of my career.”

BB: I’ve got to tell you that this book, Beyond Entrepreneurship 2.0, BE 2.0, is such a generosity, it’s so generous. For those of y’all who have not read it yet, the map is in the center of the book, and it’s not just a map, it’s got a legend, where Jim tells you, “Okay, here we are in the disciplined action stage. Here are the three chapters you should read from this book, put them with this reading.” It is… Literally, you have laid it out for us. It’s very generous.

JC: I really do think of it as I move on to the second half of my intellectual career, I really wanted to be able to hand to people “If I’m not here, here’s the map. And I trust you, you’re great students, you don’t need me. Follow the map and use your best judgment, and you’ll probably be in pretty good shape.” That’s what I wanted to give. And you mentioned also generosity. Beyond Entrepreneurship 2.0 is an act of love for me because kind of the other spark of what really drove this is there’s a co-author on this, Jim Collins and Bill Lazier. And Bill died in 2004, and Bill was the closest thing to a father I ever had. And I would not have done any of the things I’ve done were it not for Bill Lazier. When Bill died in 2004, I knew I really wanted to write something about Bill. And I didn’t want to write an ephemeral article or a thing for the alumni magazine or an obit, I wanted something enduring and worthy of writing about Bill. And it sat there for a really long time, and then Joanne, who just runs through my life as the… I sort of think of it as she’s my guidance mechanism in my head for all my erratic propulsion energy.

JC: And she had this wonderful idea. She said, “Why don’t you go back to the first book you ever wrote?”, which was Beyond Entrepreneurship. And what that book was about was the word beyond. It wasn’t about being an entrepreneur, it was about… I think of a Brené Brown having started as a successful business. Now, how do you go from there to an enduring great company? It’s beyond entrepreneurship. That’s what Bill and I wanted to give people. And it was based on our course at Stanford, and it had a very loyal following, but a small following. It got kind of dwarfed by all my later books. But for some people, it’s still their favorite. Reed Hastings read it every year for more than 10 years to bring him back to center in building Netflix. Joanne said, “It deserved more attention than it got. Why don’t you upgrade it, add new material, maybe put the map in there? But most important, write about Bill and write about what you learned from Bill and how you would not be who you are without Bill.” And it’s still by Jim Collins and Bill Lazier, and Chapter One is “Bill and Me,” and about the life lessons I gained from this truly generous and incredible mentor.

JC: And the most important thing is, I’m thrilled to have the map, what I am sharing Bill with the world. I was sitting there in Stanford Chapel after Bill died, and there were all these people in that chapel. And Bill had totally transformed my life. When Bill died, I cried really hard, and it was such a difference of how I cried. Because when my father died, I cried for what I never had. And when Bill died, I cried for what I had lost. And now to be able to honor Bill with a book that brings what we did together back to the world and to offer Bill in my words to the world is an act of love and, I hope, generosity.

BB: It was my favorite book. And then now, this is my favorite book. And when I read, “Never stifle a generous impulse,” which is one of the things that Bill taught you, right, one of his lessons?

JC: Yeah, it was inspired by a phrase that Bill Hewlett would use, but Bill liked. That was Bill. Never stifle a generous impulse.

BB: I thought to myself, “Man, he is putting that into practice in this book.” Like, this is an offering, and you can feel the love in this book. And I’ll tell you how you can feel it; there is a warm hand around the shoulder, let me walk with you through this vibe in this book. And you feel you with your arm around my shoulder walking me through it, but you also feel Bill.

JC: Exactly.

BB: And the way you laid this book out is sheer genius. The fact that over half the content is new…

JC: Almost half, but not quite.

BB: Almost half, okay. But there’s a slight difference in the page color, so I can see what was the original, which was so meaningful for me, and then you coming in with your 2020 thoughts. It really truly is such an homage to Bill and such a gift to us as the reader.

JC: It’s interesting because… I’ve got to share with you a little story of what happened. So Joanne had this idea, and then I raised it with… There’s sort of an odd little back story of luck event in life, which is that it so happened that the editor on Good to Great had moved over to found the imprint, Portfolio imprint, at PRH. And PRH had bought Prentice Hall, which was the owner of Beyond Entrepreneurship. And so the person who’s been the editor, so I called up Adrian, Adrian Zackheim, and I said, “This idea about coming out with this new edition and an homage to Bill,” and Adrian jumped all over it. But then I made a mistake. I was like, I didn’t do it. I started playing around with the words, the original words that Bill and I had written. And I got all tangled up because I’m a different writer than 30 years ago. And also I was kind of messing with what Bill and I had actually done together, and it was almost kind of trying to become like writing 30-year-later Jim views sort of feel. But in a sense, that would sort of put what Bill and I did together kind of begin to erase that, which is the opposite of what I wanted to do. So I actually threw it out. I was like, “I can’t do this, I don’t know how to do this.” And I wasn’t going to come out with it. I just put it in a drawer. I just was like…

BB: Really?