Brené Brown: Hi, everyone. I’m Brené Brown, and welcome to the Dare to Lead podcast.

BB: This is where I squeal and go like, oh my God. I’m talking with President Barack Obama about leadership, about family, about commitment to service. This is just… This conversation was so important for me, not just as a person and a leader and a citizen, but I have to say as a researcher. I’ve been studying this skill about the transformative power of holding opposites, knowing that two things that feel competing and conflicting can both be true, and how the ability to straddle these kind of paradoxes really leads to transformation, and it’s hard to observe this when you’re working with leaders, it’s hard to talk to people about it. A lot of times people do it without language-ing it.

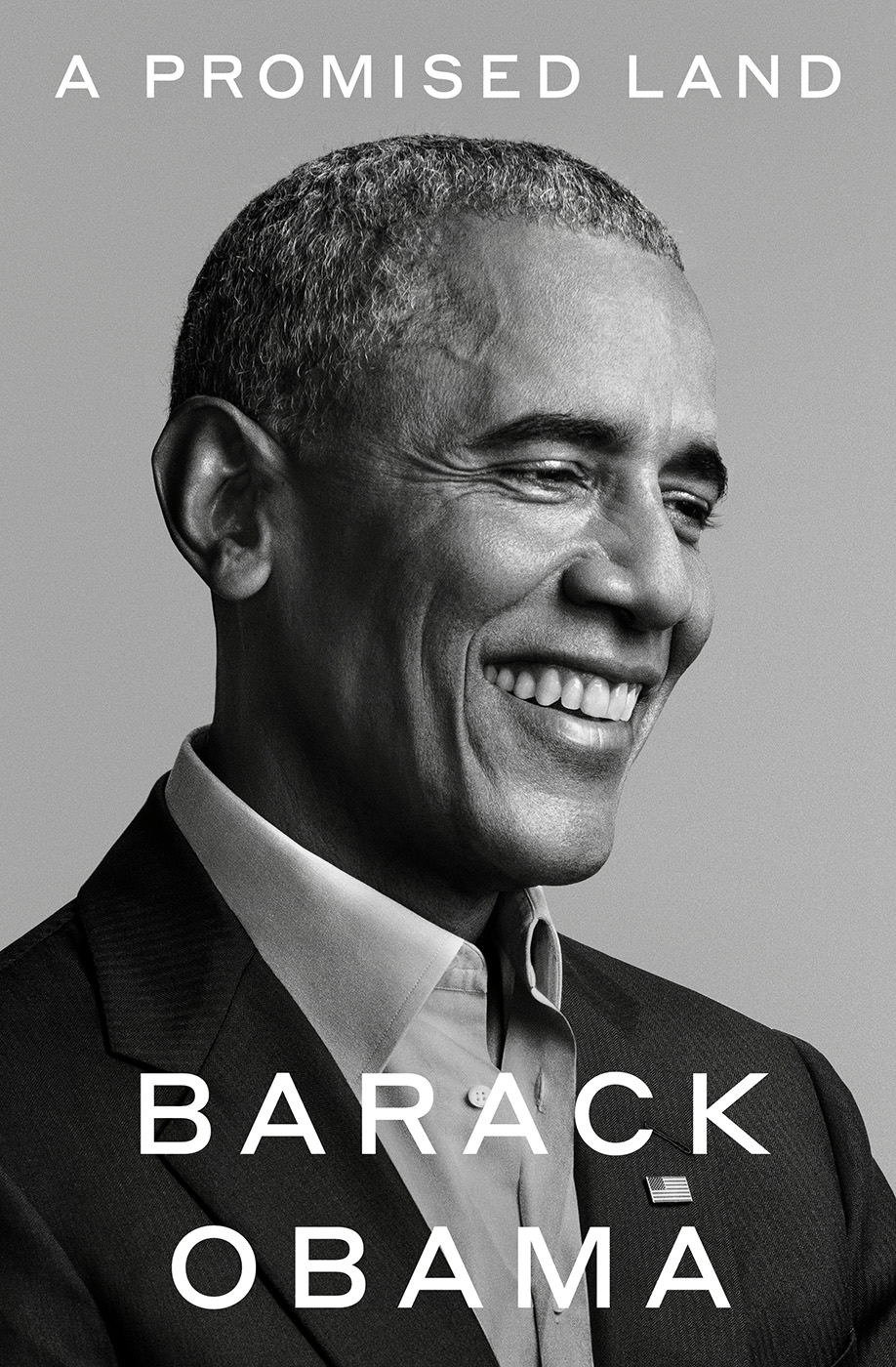

BB: But then you dive into President Obama’s new memoir, A Promised Land, which is 700 and something pages starting with growing up, and you see how this skill isn’t taught, instilled, how it comes into play in moments of national crises. I think it’s a very different conversation with President Obama than you’ll hear in other places, because we really talk about his life, his work, we talk about the new book, A Promised Land, but we also dive into the power of vulnerability, leaning into uncertainty, and why that rare skill of holding the tension of opposites makes us better leaders, partners, and parents. Excited to have you all join us.

BB: Barack Obama is the 44th President of the United States. He was born in Hawai’i to a mother from Kansas and a father from Kenya. Obama was raised with help from his grandparents, whose generosity of spirit reflected their Midwestern roots. After working his way through college with the help of scholarships and student loans, Obama moved to Chicago where he worked with a group of churches to help rebuild communities devastated by the closure of local steel plants. In law school, he became the first African-American President of the Harvard Law Review, then he returned to Illinois to teach Constitutional Law at the University of Chicago, and to begin a career in public service, winning seats in the Illinois State Senate and the United States Senate.

BB: On November 4, 2008, Barack Obama was elected the 44th President of the United States. The Obama years were ones in which more people not only began to see themselves in the changing face of America, but also began to see America the way he always has, as the only place on Earth where so many of our stories could even be possible.

BB: President Obama and his wife, Michelle, are the proud parents of two daughters, Malia and Sasha. In our conversation, we talk about it all. We talk about navigating marriage, we talk about raising kids, we talk about hard decisions, and we talk about the importance of the yes/and.

BB: Mr. President. Hello.

Barack Obama: Are you in Houston?

BB: I’m in Houston.

BO: How was your Thanksgiving?

BB: It was small and weird, but great. How was your Thanksgiving?

BO: Same. My daughters have been with us for months now, and I’m fine with it. I don’t know how they feel, but like I’m just move in, there’s no reason for you ever to leave. It’s fine.

BB: Oh, man, me too.

BO: How many kids you have?

BB: I have a 21-year-old senior, and I’ve got a 15-year-old freshman in school here in Houston, so the 21-year-old tested, quarantined, and came home for a week and it was amazing.

BO: That’s great. How’s the 15-year-old holding up?

BB: Tough.

BO: Yeah, if you’re 15 to 19 where so much of your life is getting away from your parents, spending time with your friends, figuring out your own path, they feel it more acutely. I notice with Sasha, it’s more frustrating for her than it’s been for Malia, just because she’s 19. It’s a little bit different.

BB: It’s interesting, he’s an athlete, so that’s helpful, but when there was no pool, and first year in high school, he was just like, “This is not what I had pictured.” And really trying to honor their disappointment because this is their world, and I have to be careful in not saying you think you’ve got it tough, but this is their world, you know?

BO: That’s exactly right. It sounds like he’s going to be doing okay. But you’re right, you can’t remind them that actually high school’s not that important.

BB: No.

BO: That’s not well received.

BB: No, because it’s… everything’s so big, that it’s important.

BO: Well, thank you for having me.

BB: Should we just jump in? I’ve got 18 hours worth of questions.

BO: Let’s just dive in. We’ve got one hour exactly.

BB: Yes.

BO: So I think let’s just do this thing.

BB: Okay, let me start by telling you that I loved your book.

BO: Well, thank you.

BB: Not only was it a compelling read, but it was a researcher’s dream come true, and I’m going to tell you why. There is a leadership skill set that I’ve been studying for about eight years now, that I don’t seem to be able to spend enough time with any individual leaders to really dig into, and your book just opened up incredible understanding for me, and if you’ll allow me, I would love to dig into this skill set with you.

BO: I would love to do it. You may teach me something about myself. That’s always helpful.

BB: I might. And you also have to say I’m wrong, if I’m wrong, because I could be. So you have a skill set that I saw in your childhood, I saw it in your mom, and then I think for me, I want to understand it better so we can teach it to young people, and let me tell you what the skill set is. There is a concept of holding the tension of opposites, and that for people who can do that, what emerges, some people in Jungian circles call it the third space, but there is a belief that people who can hold the discomfort of paradox are truly the most transformative leaders among us, and that it is a very rare skill set because it requires a level of comfort with ambiguity. I feel like, and I may be making this up, your life is defined by this skill set of holding the tension of duality. Does that resonate with you at all?

BO: I think it is fair. And as I write about, in some ways, it was compelled by my biography. So I am born to parents from opposite ends of the world. My mother, Midwest, Kansas, Scot, Irish, working to middle class, quintessential American story, and my father from Kenya, growing up in a small village. They meet in Hawai’i, and as I described, a lot of my childhood’s spent figuring out, “Well, how did I end up here? Who am I? What am I? How do all these strands fit together?” And I think that necessitates an ability to see a bunch of different points of view at the same time.

BO: And in my first book, Dreams from My Father, I write about the struggles of a young person, a child, and then a young man, trying to reconcile those different parts of my identity. By the time I’m President of the United States, I’ve sorted out a lot of those things, but I do think that it teaches what you just described, a sense that it is both possible and necessary to see the paradoxes, the ambiguities, the gray areas, the absurdities sometimes, of life, but not be paralyzed by them, and I think that the trick, for me at least, and what I try to describe, is to be able to say, “On the one hand, my job is to look out for the safety of American citizens as the American President. On the other hand, there is a universal interest in peace and fairness and justice outside our borders, and how do I reconcile those things, but then still be able to act as Commander in Chief and still be able to make a decision?”

BO: Or a matter of dealing with the economic crisis, being able to reconcile the fact that our free market system creates enormous efficiencies and wealth, and that’s not a system that we should want to just tear down on a whim, because a lot of people are relying on us making good decisions about the economy. On the other hand, there are parts of the economy that don’t work and are unjust and get people frustrated and angry about bankers getting bailed out, and so forth. Both things are true, and you then still have to make a decision. So I do think that for me at least, the value of what you described is that I was less prone to get trapped in dogma or a narrow way of thinking about every problem. The danger in being able to see paradox is then, as I said, paralysis of analysis, and I think that that’s something that I trained myself not to fall into that trap as much as possible. The good thing about being the president is sooner or later, you’ve got to make a decision anyway. Even if you make no decision, that’s a decision.

BB: Right. So I want to start with your mom. I have pulled out 20 examples of you straddling the tension of opposites, of forcing transformation through duality, that really changed me in a way, and also starting to open the door to helping me understand what the skill set is behind it. So one of my favorite things that you wrote about your mom, which to me just sums up her paradoxical way of moving through the world: “For my mom, the personal was political, but she would have no use for that saying whatsoever.”

BO: Right.

BB: So what does that mean?

BO: I was describing the fact that here’s a woman who was very much her own person, who married outside her race, moved to another country, shaped her own professional career, was very much in many ways a ’60s liberal, environmentally conscious and all about racial justice and all that stuff, but on the other hand, was very suspicious of slogans and would not sign on to any particular program, and would always tell me, “The world’s complicated,” and was suspicious of people who were too sure of themselves and justified putting other people down or being mad at them just because they didn’t subscribe to a very particular ideological view. And I think that that is a part of her that I inherited. I always ascribe this basic Kansas, Midwestern common sense, home-spun values that she in turn got from my grandmother and got passed down to me, and particularly now at a time when so much of our public discourse is full of people who on all sides are just absolutely certain about everything, and assume that if somebody doesn’t agree with them, then they must just be horrible people who don’t understand anything. I’ve found that to be a saving grace, that kind of approach towards life.

BB: I actually have in my notes here, you seem to have inherited her suspicion about anything that was wrapped up too nicely with a bow.

BO: Right. I think that’s a great way to put it. I learned very early on that good people could make mistakes and the best of intentions could go awry, and that people who didn’t share my values might have some redeeming qualities that I had to pay attention to, and that certainly was an important part of my politics as I moved on in life, and that was an experience that was very much reinforced when I became a community organizer after college. I think that when you’re in college, because you’re with people of your own age and you can easily select groups that agree with you on everything, it’s easier to fall into that sort of self-satisfied, self-righteous mode, and I describe how I fell prey to that sometimes.

BO: When I actually took my theories and started testing them in neighborhoods on the south side of Chicago, suddenly I started realizing, “Oh, people are complicated, and situations are complicated,” and assumptions I had made about how should black folks think about things, or how should church folks think about things, or how should poor people think about things, that actually, they didn’t neatly fit into the grid that I had set up in my head, and that I think opened me up then to actually truly listen to people. That act of listening to others, hearing them, seeing them in the round, understanding their story, became a very important part of how I was able to inspire others and ultimately mobilize the kind of coalition that took me to the presidency.

BB: Again, I probably found five or six real defining paradoxes, I think, when I look at the book. One of them was very much this tension I felt from maybe page 12 to the very end, and my guess is it’ll define the next book, which is your absolute, again, tell me if I’m wrong, love for academic, rigorous political theory and debate, on one side, and then you pick the direct opposite job of that. As an academic, I will tell you the direct opposite job of academic theory debate is community organizing.

BO: I describe in the book the path I took and living in my own head in college, and obsessing with books and theories and so forth, and then as I said, I become a community organizer, I run for the state legislature, and you are in a world where you have to act, you have to make decisions. The decisions you make are going to be imperfect. Again and again, if there’s one thing I wanted to communicate in this book, it’s that the higher up you go in politics, but I think this is true of any organization, the more you will be confronted with challenges, problems, issues that do not yield a perfect answer.

BB: Oh, I hate that.

BO: I know, it’s frustrating, and it’s worse when you become President because, as I said, by that point, anything that actually has a good answer, somebody else solved a long time ago. The only thing that lies on your desk is the stuff that nobody else could figure out, and you know that something about it is impossible and it’s going to be a mess and somebody’s going to be mad about whatever you do. And what I try to describe, though, is just because something doesn’t have a perfect answer doesn’t mean it doesn’t have a better answer. So my interest in rigorous debate, good analysis, good facts, making sure that we have looked at every problem from every angle is not because I think that you can actually come up with a perfect answer, but it’s that by engaging in that exercise, you can at least eliminate bad answers, you can at least have some humility around what outcomes you should expect. you can guard against some outcomes that are less than optimal, you can hedge your bets a little bit, and so at the end of the day, you can make better decisions, even though you know they’re not going to be perfect.

BO: And I do think that the benefit I got from my academic training, and that I retained all throughout my community organizing and my legislative career and then working in the Executive Branch, was still having respect for the fact that, as complicated as the world is, there are still tools we have and the capacity to reason things out that we ignore at our peril. And obviously we’re living through a moment like that right now with the pandemic. I think a lot of people have noted that our best epidemiologists didn’t necessarily understand COVID-19 perfectly at the beginning, made some misjudgments.

BO: No matter how good our scientists and health experts were, this was going to be a big messy problem, but we could make better decisions rather than worse ones, we could constantly improve our response, and those countries that did so have had better outcomes and those countries that didn’t have had worse outcomes, and that translates into thousands of lives that are either saved or not, and I think that’s true of just about any problem that we face.

BB: It’s interesting to me because when I was reading about your childhood and you were writing about your prep school days in Hawai’i, you wrote you felt pulled in different directions. You write: “It was as if, because of the very strangeness of my heritage and the worlds I straddled, I was from everywhere and nowhere at once, unsure of where I belonged.” And the minute I read that, I got this huge lump in my throat, and I thought immediately of Maya Angelou. And I thought immediately of her quote, “You are only free when you realize you belong no place. You belong every place. No place at all. The price is high. The reward is great.”

BO: Yeah.

BB: You seem to develop, especially outside of college, a real sense, maybe forced because of your biography, a real sense of belonging to yourself. I was a union organizer back in a previous life, Communication Workers of America, I worked for AT&T, and I was a union steward and organizer.

BO: CWA?

BB: Yeah, CWA, 61-43, San Antonio, baby. And this theme kept coming to me because I’ve been around so many organizers in my life who said the analysis, the data gathering, the theory, that’s for those people over there, “We’re on the ground, tactical, actionable, we’re walking with parents to legislator’s office to get new sidewalks,” and then I’ve been around academicians who say, “You know what? We’re not community organizers, we’re here to solve bigger problems.” But the story I make up anyway is that this inherent belonging to yourself led you to a refusal of diminishing what was important about both of those things. Is that true?

BO: Yeah. Dr. King, in talking about civil rights and rising out of the scourge of Jim Crow and segregation, he’d talk about both/and approach not an either/or approach, and I am a big believer generally in both/and, so I think that in pursuit of social change, you need to have policy and analysis and smart ideas, but you also need stories and grit and passion and courage. And by the time I was, let’s say, out of law school in my early 30s, I had enough confidence in me maybe not having all the answers, but at least being able to figure out a way forward, not thinking that somebody else had better answers than I did, that I could think for myself and evaluate the world around me just about as well as anybody else could, that I didn’t feel as if I had to narrow my path to one way, that I didn’t have to solve problems just through one approach. And I do think that that was a useful quality and would have been a useful quality even if it hadn’t been in politics, even if it was in some other field.

BO: When I think about friends of mine or people I’ve known who excelled, let’s say in finance, it’s interesting to find out how many of them were Liberal Arts majors, who still draw on their understanding of human nature in terms of making decisions about their business. When I think about great scientists, it’s interesting to discover how many of them actually have deep religious faith, despite the fact that it’s been posited that somehow religion is contrary to science, but they don’t see the contradiction. We set up these categories and constructs, but those can also be traps, and that we want to make sure that we don’t fall into the false security of these categories. I think that’s important, and that’s true, certainly, with a lot of the issues that I dealt with as President, but I think it’s also true… When I talk to my daughters, I tell them this is true for life, not just public life.

BB: Let me just ask you maybe a very vulnerable question, especially in the cultural world today. I know from my research, our sense of belonging with other people can never be greater than our sense of belonging to ourselves, but God, I have to say that, for me, that gets lonely sometimes. Like these ideological bunkers where people are all together and they all hate the same people, they can be very seductive. Did you find that middle path, which I actually do believe is the only path to real transformation, did you find it to be lonely ever?

BO: Yeah. Well, as I write in the book, nothing hurts more than when you’re criticized from your own group.

BB: Oh, God, that’s true.

BO: Whether it’s your own political group, your own religious group. Whenever you’re pushing back against your friends, that’s always harder than pushing back against your adversaries. Whenever you’re challenging the conventional wisdom of your own cohort, that’s always toughest. And so, yeah, that can be lonely sometimes. The thing I try to express in the book, that I try to express in my politics is just because you don’t fall neatly into camps or reject certain labels, it doesn’t mean that you don’t have a clear sense of right and wrong. It’s just that you scramble the categories. I guess what I mean by that is I have a very clear set of values that I think are important. And I’m proud of the fact that many of those values have been advanced by my political party, the Democratic Party, but I am always reminding my fellow Democrats that the President who I think, as much as anyone, embodied the values I care about was a guy named Abraham Lincoln, who was the first Republican President, that some of the values that I care most deeply about were systematically rejected for much of modern American history by Southern Democrats. So, I’m not going to presume that one political party has a monopoly on values versus another.

BO: And I’m going to take individuals and groups of people on their own terms and not make assumptions ahead of time about whether or not I can connect with them over their values. I think that’s become more difficult today. And the reason is partly, I describe in the book, and this is a phrase that other writers coined and have used, it’s not original to me, we’ve gone through what’s been called the big sort. Where it used to be that you had a bunch of liberal Republicans who were for civil rights and were for the environment, and you had a bunch of conservative Democrats. And each party was this big loose potato sack full of quirky regional differences and predispositions.

BO: And so you could find common ground and people couldn’t make a whole set of conclusions about what you did or didn’t believe just based on your party affiliation. And for a variety of reasons, because of first the Civil Rights Movement and reactions to African-American and minority claims on the body politic, because of cultural issues around gender, abortion, and the LGBTQ community. Because of divisions around urban versus rural.

BB: Huge.

BO: And because of the splintering of our media, suddenly what you have is this perfect alignment where, okay, you check off 10 boxes of where you stand on issues and that means you’re on this side and on those other issues, you’re on that side. And that’s continually reinforced by the media and what news stations you choose to watch and so forth and so on. And I think that that is part of what’s made it lonelier for people who are trying to think things through on their own. It’s led to a lot of the polarization that we’re experiencing, and how we get out of that is going to be a big challenge. I don’t think there’s a silver bullet to it, but it begins by the same advice my mother gave me very early on in this book, which is, “Look, the world’s complex and spend some time listening to people and their stories and understanding the context through which they’re processing the world.” If you can do that, then it’s possible that you can grow that community and make it broader rather than narrower.

BB: It’s funny, when I was writing Braving the Wilderness, I call the seductive nature of those ideological bunkers common enemy intimacy, we don’t even know each other or each other’s stories, but we just hate the same people. And how counterfeit that intimacy is that it makes people afraid to take one step out of that bunker, to say, “I actually disagree.” Understanding that loneliness, of taking an unpopular stand, of feeling alone in the wilderness, that’s a part of belonging to yourself. It’s a part of staying in alignment with your values, and that’s the heart of daring leadership.

BB: One of the other big kind of dualities that I saw in the book, and let me just tell you, this part made me crazy, was home and work, family and work.

BO: That’s a big one.

BB: I’m going to tell you this. I read this book with three other people, and the first time you went to ask Michelle a question, I think you were going to run for office in Springfield, or… It was like two or three times you did this, you would say Michelle was reluctant, she wasn’t sure about it, she didn’t like politics. And then the next chapter would open, it was like, “Okay. So, I’m putting my committee together.” And I was like, “Wait a minute, I’m missing pages.” No, I was really like, “Wait a minute, my book is missing pages.” So, I called the other people I was reading with were women, and I was like, “Is your book missing pages?” And they said, “What do you… ” I said…

BO: Call Michelle.

BB: I wish I knew her well enough to just have her on speed dial because I’d be like, “I’m missing pages because… How did he get from I talked to her about it, to I’m doing it?” Then I realized something really hard that caused a huge fight with me and my husband, that we have the same conversations about work and commitments and taking on a new book or something. And then he knows that he has a veto vote and that I have a veto vote, but he says, “I’m worried about it, I’m concerned about it.” But that’s not enough for me. I want him to enthusiastically love every minute of it. Say that he was wrong about having concerns about it. Those were the pages I was missing.

BO: That never happened, but I think you just really put your finger on both an important dynamic between me and Michelle, but also one of the things that has allowed us to maintain a strong marriage through a lot of difficult stuff that we did together, and that is that you do have to communicate that at the end of the day, the other person is your highest priority, they do have veto power, but if they choose not to exercise that veto, that doesn’t automatically mean they were happy about the decision, it just means they’re not going to stop you from doing it.

BO: And that’s okay, that’s alright. It goes back to complexity, what we just talked about. It’s not that you were missing pages, if you read those chapters, it’s that Michelle was unconvinced, but at the end of the day, she believed enough in the sincerity with which I was pursuing a political career, had enough faith that I would actually do some good, and knew that she had in her back pocket the ability to stop it if it was doing harm to our family, that she was willing to go along with it, but made clear to me, “Buddy… ” As I write in the book, at one point, “Don’t count on my vote. I will not stand in the way, but I’m not sure that this is going to work.”

BO: And part of the challenge I think that we all have, if we’re in a partnership where both people have careers and they’re busy, have ambitions in the best sense of wanting to have a positive impact in the world, is our society is not that well-organized for child-rearing. The burden invariably falls heavier on the woman, not just because of external pressures, but internal pressures. I write about the fact that Michelle loves her mom, she ended up being a huge part of us being able to manage the White House and keep our sanity. She wanted to be in her own mind as good of a mom as her mom had been to her, but her mom didn’t have a professional career the way Michelle did, so now she’s feeling guilty about, “Am I being a good enough mom, am I good enough on the job?”

BO: And so in those circumstances then she’s not just expressing a set of questions about whether I’m making good career choices in running for the U.S. Senate or the Presidency, she’s also communicating, “Dude, this is going to place extra burdens on me, and are you clear about that?” And I respected the fact that she didn’t just bat her eyes and say, “Okay, honey, whatever you want, because I so believe in you.” The fact that there was some tension and resistance there on her part did two things. One is, it made me really have to check, “Okay, is this worth it? Because she’s not thrilled about it, and have you really thought through whether you can win a campaign, is it worth it, what you can get done,” etcetera?

BO: The second thing, it was a constant ballast for me once I became President, for example, her reminding me, “Alright, now we’re doing this, but you have these other commitments, your daughters need you, I need you. I’ve got certain expectations. And so if you want to do this, just understand it may feel like you shouldn’t have any other obligations other than just being President, but I’m here to tell you, ‘No, I’m still expecting you to be a good dad and a good husband.'” That was useful to me. At the end of the day, I actually thought it made me a better President, but it wouldn’t have happened if I was not comfortable with her expressing tensions in her own inimitable way, creating some discomfort around some of the decisions that I made.

BB: It’s one of the things that I really learned from the book about myself, so thank you for that. I think my marriage will be better for it, actually, because a really unfair ask when I say that I’m going to take on a new something, it’s the power again of holding those opposites, because I do think in a transformational way, they served each other for you in a real way, just from moments in the book where you would be sitting, trying to make a very hard decision, and you’d see the girls on the swing set and you would remember, “Oh, my God, why am I here?” Or there was a quote of you really challenging yourself, always questioning your own motivations. You write, talking about Michelle, “Why would I put her through this? Was it just vanity or perhaps something darker, a raw hunger, a blind ambition wrapped in the gauzy language of service, or was I still trying to prove myself worthy?” Again, tell me if I’m wrong, but that tension seemed to drive you to ask hard, hard questions of yourself, and how you were going to be both in service of your family and the country.

BO: Yeah, and that spills over then to asking hard questions about your work and your decision-making and being comfortable asking yourself those questions. I think that all of us who are type A, high achiever types, we can talk ourselves into justifying all kinds of sacrifices in pursuit of a goal. And some of that is healthy, but sometimes it makes us sloppy. It makes us sloppy in terms of thinking that whatever means justifies the ends. It can make us sloppy in terms of feeling okay when we’re not there for our family or our friends, because look how busy I am, look who important what I’m doing is, etcetera. And you get in the habit of justifying whatever you do, that spills over into your work.

BB: That’s right.

BO: And for me, at least, it’s always been useful, and Michelle has been a contributor to this. And no doubt I married Michelle precisely because she was that kind of person who was not going to give me a pass on stuff, because I found that it would force me to ask questions. I touch a little bit about this in the book when I’m describing decisions around war and peace and deployment of troops.

BB: That’s right.

BO: The hardest decisions I made as President invariably involved deploying our incredible men and women in uniform into theaters of war. And very early on when I came in, despite having pledged to be the president who brought an end to the war in Iraq, I had proposed that from the start. I had also said, “We have to get Afghanistan right.” The situation was deteriorating there, and I had to deploy more troops. And I give this speech at West Point where I’m looking out over a bunch of 20-year-olds and 21-year-olds who… You know, they’re not much older than Malia. And I know that if I send additional troops, some of them will be grievously injured, some of them may not come home. I describe visiting Walter Reed and the experience of these incredibly courageous, tough Marines and soldiers who are proud of the sacrifices they’ve made.

BO: And yet I have to remind myself, this is part of what war is. And so even a good war, even a war that’s justified, even when it’s necessary to protect the American people, there’s still a price to it. And so you can’t be casual about it. And in fact, I describe how, at one point in my presidency, somebody suggested I shouldn’t visit too much with wounded troops because it starts clouding your judgment around national security issues. And I vehemently disagreed with that because I said, “No, actually, I need to see the cost of this to make sure that when I make a decision about deploying our troops, that I understand what that means and what the sacrifices are and the cost for so many of these young men and women and their families.”

BO: And so I guess my point is, is that having those questions raised in my own pursuit of my career got me in a good habit, I think, of when I was President, asking tough questions of myself, making sure that my motivations were not because I was trying to prove something or because I was trying to be a big shot, or I was trying to get back at a critic or some other reason of expediency. But if I made a decision, it was because I genuinely thought that was the right thing and the best thing to do. And the best assurance for me of knowing I’d made a good decision is if I knew the downsides of it, if I understood the costs of it, if I had internalized that there was a price to pay for it.

BB: Are you familiar with the Stockdale Paradox?

BO: No, go ahead, please.

BB: I read about it in Jim Collins’ book Good to Great. Admiral Stockdale was a prisoner of war. Tortured many times. And Jim Collins interviewed him for the book. And he asked Admiral Stockdale during his time as a prisoner of war, “Who didn’t make it out?” And Stockton replied, “That’s easy, the optimists. Christmas would come and go, they thought they’d be out by then, they thought they’d be out by Easter.” And so the Stockdale Paradox reminded me of you because the quote is, “You must never confuse faith that you will prevail in the end, which you can never afford to lose, with the discipline of confronting the most brutal facts of your current reality, whatever they may be.”

BO: Yeah, I think that’s a wonderful quote. It embodies the way I think about optimism and the way I think about the country. I arrived on the national scene based on my Convention speech in Boston in 2004, and I described the audacity of hope, and later on people would say, “Oh, Obama is so idealistic.” He said, “There’s no red states, no blue states. There’s the United States, and it’s such a hopeful speech, and then later on, look what happens, we’re so divided and angry.” I try to explain to people, I said, “Read that speech carefully.” I’m very particular in saying, I’m not talking about blind optimism when I’m talking about hope, I’m talking about the hope of slaves sitting around the fire singing freedom songs. I’m talking about hope in the face of uncertainty, hope in the face of difficulty.

BO: That sensibility is what you describe, it is something that I’ve found very valuable. The people I tend to admire most, whether it’s the Nelson Mandelas or the Abraham Lincolns of the world, the Mahatma Gandhis, they are folks who fully absorb the tragedy of their times, of their moment, and don’t sugar-coat it.

BB: That’s right.

BO: And it’s only after they have absorbed that pain, that hardship, where it’s the Civil War or the oppressive nature of Apartheid or the challenges of colonialism in India, it’s only after you fully absorb that, and then you still insist, “We will prevail.”

BB: Yes.

BO: That’s when there’s a depth to your hope. It’s hard won, it’s not easy, it’s not based on, “Everything is always going to work out.” It’s not premised on the notion that progress is a straight line. Because progress zigs and zags, and sometimes it goes backwards before you go forward, and if you can get there, then I think you can get stuff done, and you can also win over trust from people, because you will have hardships and things will not work out at certain points. I describe in the book, I get elected to the U.S. Senate, I don’t intend to run for President, it takes on a life of its own, partly, as I explain, because I’m sort of a shiny new object, and I had this opportunity to run, I decided to get in and I win Iowa, which nobody expects, because I’m running against much better known Hillary Clinton [inaudible] and Iowa is 98% white and rural, and everybody’s so excited.

BO: And then a week later, I lose in New Hampshire. We were all favored to win, the polls showed we were going to be up by 10. And I describe in the book how although Iowa showed I might get elected President, it was the loss in New Hampshire that actually showed my staff and my supporters that I might actually be able to be a President, because what I found was a useful quality in myself was I actually am pretty clear-headed when all hell’s breaking loose. When things are going bad, I tend to actually to be focused and make good decisions.

BO: And I think it traces back to what we just talked about, this sense of I’m not anticipating things always being smooth. And I don’t get too high when things are going good, I don’t kind of extrapolate and say, “Oh, they’re always going to go good.” Conversely, when things go haywire, I don’t just keep on following that all the way into despair, I assume, “Alright, well, this is kind of the nature of the human condition, some ups and downs, and we’ve just got to kind of muscle through and figure it out.” And that I think not only was useful for me, but it’s useful if you want to lead a team or a country. People watching how you respond when stuff’s hard, not when stuff’s easy, I think is telling. And that’s how you can really make a bond with team members is if they see you responding with some grace under pressure.

BB: My favorite moment from what you write in the New Hampshire loss was, until then you had not fully embraced the Yes We Can slogan…

BO: Yeah, that’s right.

BB: But in the final paragraph, around the loss in New Hampshire, people on your team, even though you’d just lost, started chanting it, and you were like, “Oh, that’s what Yes We Can means.”

BO: Yeah.

BB: God, goosebumps.

BO: That’s exactly right. You have a good memory. In fact, what had happened was, we had incorporated Yes We Can into our victory speech. So this unexpected loss… Again, the public polls were showing us, and our internal polls were showing us up 10, which in a campaign is a big lead, it was a huge surprise for us to lose. And what I actually told my speech writer was, I said, “Other than acknowledging the loss and congratulating Hillary Clinton, let’s not change the speech, let’s talk about Yes We Can, let’s talk about what our vision is.” So it was a good example of the fact that I was going to give the same speech whether I won or lost, because the point wasn’t this momentary event in New Hampshire, the point was, “What’s our broader vision for the country?”

BO: And it’s true, and I always tell them, whenever people say, “Oh, man, you’re such a smart politician,” that in fact, very early on when I was running for the U.S. Senate, somebody proposed this slogan, Yes We Can. I said, “No, that’s corny. Why would we want to have that as a slogan? That’s not very catchy.” Which is another good leadership lesson, you don’t know everything, and it’s very valuable as a leader to realize you better have a good team around you, because you’re going to be wrong a bunch and meet people who don’t mind calling you on it.

BB: Do you have time for the rapid ten?

BO: Absolutely.

BB: Okay, fill in the blank for me. Vulnerability is…

BO: Inevitable, be open to it.

BB: What is something people often get wrong about you?

BO: That I am aloof. This is something that developed in Washington, I think because Michelle and I didn’t do a lot of salon parties and schmoozing, because we had small kids, but I actually love hanging out with people, I wouldn’t have been elected President if I didn’t.

BB: I also sometimes wonder if aloofness is assigned to people who pause and think about things, which is not…

BO: Well, that might be true, too. I talk too slow.

BB: No, because you think.

BO: I’m very deliberate.

BB: Oh, you know what, look at these three words I have written down, discipline, deliberate, paced. But I think if leaders want to occupy that middle space, you have to give yourself more time to think.

BO: Yeah.

BB: Okay, let me ask you the next one, what’s a piece of leadership advice that you’ve been given that’s so great, you should share it with us or so crappy, you need to warn us about it?

BO: The best piece of leadership advice I got was when I started community organizing, and the guy who hired me said that I had to spend the first month of my job going around and just listening to people and their stories. Instead of telling people what they should care about, listen to find out what they actually do care about. And people tend to make the mistake of thinking a leader is the person who’s doing all the talking and telling other people what to do as opposed to hearing other people and then helping empower them.

BB: Spoken like a true community organizer, I have to say. What’s one stereotype or myth of leadership we need to let go of?

BO: That to be a strong leader, you have to be domineering.

BB: So what is a hard leadership lesson that the universe just keeps putting in front of you and will continue to put in front of you until you nail it?

BO: So this is less true, I think, if you’re running a business or an organization where you’re interacting with everybody who is part of your team, but if you’re in the public realm, people respond emotionally more than they do analytically. And it doesn’t mean that policy doesn’t matter, ideas don’t matter. Those things matter, but it does mean that when you’re talking about mass communications, analysis, logic often gets overwhelmed, and so you have to at least take that into account in trying to move lots of people in a particular direction.

BB: What is that quote? People may remember what you said, but they’ll never forget how you made them feel.

BO: Yeah. That’s exactly right.

BB: I think that’s Maya Angelou, too. Okay, what’s one thing you’re super excited about right now?

BO: I’m super excited about the work I’m doing with the Obama Foundation, because our whole premise is that there are these amazing young leaders, not just all around the country, but all around the world. They’re not where everybody always expects them to be, they’re not all in a bunch of Ivy League schools, they’re not all even necessarily college grads. They’re in neighborhoods, they’re in places of worship, they’re in businesses. They all have this interest in transforming our institutions so that they work better to reflect the values of this upcoming generation, which are really good values of inclusion and environmental sustainability. And I’m really excited about spending the next phase of my life giving them tools, platforms, ways to connect with each other so that old guys like me can get out of the way and they can take the baton and run with it.

BB: I got to say, I did some Dare to Lead work with the first cohort of Obama Fellows, and I was blown away by the depth and breadth of things they’re working on, just…

BO: Yeah. It’s really cool.

BB: Almost freaked out by how incredible they were. Yeah. Okay, what’s one thing you’re deeply grateful for right now?

BO: My children turning out as fabulously as they have.

BB: Amen. Alright, you gave us a mini mix tape of five songs you can’t live without. “What’s Going On,” by Marvin Gaye, “Don’t You Worry ‘bout a Thing,” Stevie Wonder, “Like a Rolling Stone,” Bob Dylan, “My Favorite Things,” by John Coltrane, and “Sinner Man,” by Nina Simone. In one sentence, what does this mix tape say about President Barack Obama?

BO: Fantastic taste in music.

[laughter]

BO: Come on. I challenge any of your listeners, listen to those five songs. If you’re not in a better place at the end of it, I’ll give you your money back.

BB: Check your pulse.

BO: Yeah, exactly.

BB: Okay, I have to just end with this question because I learned it from you. Can you quickly for me describe your world as it is and how you’d like it to be, which was your big question when you were a community organizer, right?

BO: The world as it is, it is divided, anxious, frustrated, tribal. The world as I’d like it to be is more unified, more equitable, more generous, and less materialistic. One thing, and maybe this is a function of age, as I mentioned early in this interview, I’m a believer in the free market as a mechanism to create incredible wealth for societies, and it is compatible with individual freedom in ways that I think are really powerful and important, but I think that both on the left and the right, and in the center, we are so obsessed with stuff and haven’t spent enough time thinking about the joys and meaning that come from human connection, purpose, and service.

BO: And I think that us spending some time thinking about that is an area where we could potentially unify. I think that both the evangelical Christian and the progressive liberal actually has a sense that they’d like to see a return to values and meaning and spirituality, and how we reconcile that with a big, complicated urban society, I think, is a good project for all of us.

BB: And not lacking complexity.

BO: No.

BB: No. Thank you so much, President Obama, I really appreciate it. I’m a better leader having read this book, and I think I understand myself better. It was important.

BO: Well, I’m a better leader from having heard what you read in the book, so thank you for being such a careful and earnest reader. That’s what every author hopes for.

BB: Thank you.

BO: You bet.

[music]

BB: Y’all know that my favorite thing in the world is talking about the complexities of seeing things from all sides, unpacking, seeing things integrated completely, and also the joys and purpose and meaning that come from human connection, and service. So for me, this conversation was really such an incredible gift, as is A Promised Land, the book. It is long. No kidding, it’s 700 and something pages. I will tell you that I went back and forth between reading and listening, which is pretty normal for me. The only time I don’t do that is if I don’t like a narrator, but in this case, President Obama narrates the book and it’s really beautiful. And so I highly recommend it as not just a citizen or a lover of history, but as a person, as a mom, as a partner. He’s an incredible and gifted teacher, so I love it, A Promised Land. If you want to follow President Obama on social, he’s @BarackObama on Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook, and his website is barackobama.com.

BB: Again, I know that time is the great unrenewable resource, and that you lend me an hour or maybe even two for both podcasts, for this one, and Unlocking Us, a week to learn with me, to walk together on this kind of journey of figuring out who we are and how we show up in braver ways. I’m always incredibly grateful. Last week on Unlocking Us, I talked with David Eagleman, a neuroscientist and New York Times best seller. We talked about the brain and how it works. It’s mysterious, constantly changing, but it’s also malleable and up for new challenges if we keep giving it new challenges, which is a really important learning for me. And we talk about Dr. Eagleman’s book, Livewired: The Inside Story of the Ever-Changing Brain. So check that out.

BB: I appreciate y’all. Stay awkward, brave, and kind. And when you find yourself in that uneasy, awkward, cringy place of trying to pick sides, grab each of those sides with one fist and think, “Is it possible that both these things may be true, and is there a transformation waiting for me somewhere in the middle?” See you all next week.

BB: Dare to Lead is a Spotify original from Parcast. It’s hosted by me, Brené Brown, and it’s produced by Max Cutler, Kristen Acevedo, Carleigh Madden, by Weird Lucy Productions, and sound design by Kristen Acevedo. Music is by the amazing Houston band, The Suffers, and the song is called “Take Me To The Good Times.”

[music]

© 2020 Brené Brown Education and Research Group, LLC. All rights reserved.