Brené Brown: Hi everyone, I’m Brené Brown and this is Unlocking Us.

[music]

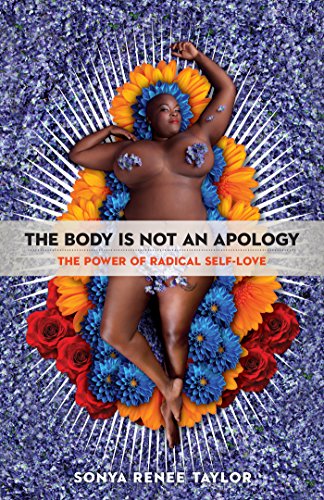

BB: Today, we’re talking to Sonya Renee Taylor. She is an artist, activist, and founder of The Body Is Not an Apology. I think just the title, The Body Is Not an Apology, is enough to take your breath away, but if you need more, stay tuned because she’s coming with a big ass key to unlock some really hard stuff. For me, and I think for all of us. So, stay tuned for my conversation with Sonya Renee Taylor. I think it’ll make a difference.

[music]

BB: Alright, so let me tell you a little bit about Sonya Renee Taylor. She is the founder and radical executive officer of The Body Is Not an Apology, which is a digital media and education company with content reaching half a million people each month. Sonya’s work as an award-winning performance poet, activist, and transformational leader continues to have global reach.

BB: She is a former national and international Poetry Slam champion, author, educator, and activist, with audiences across the United States, New Zealand, Australia, Germany, England, Scotland, Sweden, Canada, and the Netherlands. She also does a lot of work inside prisons, with mental health facilities, homeless shelters, universities; she does some incredible work with festivals and also public schools across the globe. Let’s just jump right into this conversation, because again, just the title of the book, ooh, that’ll be enough to get your attention.

BB: We have to just jump in because I have so much… I have so many questions to ask you, I have a ton of gratitude to share with you about this powerful work, and so I just want to jump in. But before actually we even start with the book which I want to talk about, The Body Is Not an Apology: The Power of Radical Self-Love, everything about the title, subtitle, and photo on the front of this book was screaming, “Don’t get near it, Brené, it’s gonna jack you up.”

[laughter]

BB: “Don’t do it, Brené.”

Sonya Renee Taylor: “Don’t do it, don’t do it.”

BB: Yes, but I did it and I’m still in pain and awe, but I’m so glad I did it. But before we even start with the book, I want to tell people kind of how we met, because there’s something important in it, right?

SRT: Yeah, totally.

BB: So, I woke up one morning and I was taking my morning hit of social media, which is not good for me, but I was doing it anyway.

SRT: I take a daily toke. A morning toke as well.

BB: Do you take a good morning toke?

SRT: I do. I do.

BB: Yeah, it’s just crap, but I do it sometimes.

SRT: Yeah.

BB: So, I saw this really beautiful quote card and I read it, and it was a quote card for me, and it was like, “We will not go back to normal. Normal never was. Our pre-corona existence was not normal, other than we normalized greed, inequity, exhaustion, depletion, extraction, disconnection, confusion, rage, hoarding, hate, and lack. We should not long to return, my friends. We are being given the opportunity to stitch a new garment, one that fits all of humanity and nature.” And then it was signed off, “Brené Brown”. And I was like, “God, that is so good.”

[laughter]

BB: And I so did not say that. [chuckle] I wish I would have said that, but I didn’t say that. And this thing was kind of like fire, right? This quote. So, I called Genia, this amazing woman who runs our social media, and I said, “Have you seen this quote about stitching a new garment?” She goes, “Yeah, it’s so beautiful.”

BB: And I said, “Yeah, I didn’t say it.” She goes… I think her exact words were “Oh, shit.” And I said, “I’m going to respond on Twitter with this and say, ‘This is beautiful. I didn’t write it. Attribution matters.’ While you start investigating who said it.”

SRT: Yeah.

BB: And then she came back and she was like, “That is Sonya Renee Taylor.” And I was like, “Okay, great, let’s fix it.” And I bet we’ve sent, you’ve seen them probably, 10,000 tweets. We correct it every time we see it.

SRT: That is incredibly generous and kind, I appreciate you and that massive amount of labor. Because I… It was really interesting. It was such an interesting lesson when it happened to me. Somebody first sent it to me in my DMs and said, “Sonya, they’re attributing this quote.” And it was a person I did not know, and they were like, “What do you want me to do?”

SRT: And I was like, “Correct it if you know… Just correct the person who said it.” And then I started getting lots of them. And there was this moment of, “What do I do? What matters? Does it matter that the world knows I said this? Or does it matter that what was said seems to matter to people? And which one are you willing to focus on, Sonya?”

SRT: And so, there was a moment where I really just had to have this entire internal reckoning where I was like, “I trust that those words are useful for whoever it is that they’re useful for, and that the use is more important than the me being named in it. And that if I’m supposed to be named, then the universe will work that all out.” That’s what I’m trusting.

SRT: And then I let it go, I really let it go. And then I woke up and there was the message and the tweet and several people like, “Brené Brown tweeted about you!” [laughter] “Oh my gosh, Brené Brown!” And I was like, “That’s awesome and amazing.” And it was this beautiful tension between my own ego and the reality of the world and what happens to Black women’s voices in the movement of history.

SRT: And what is important, what’s most important in this moment? And those were the things that I felt like were all sort of at play in that situation. And I believe that me saying, “I trust that it will work out the way it’s supposed to work out,” is the reason why I get to be here in this conversation with you today. And so, that’s magic. [chuckle]

BB: Your heart is so much bigger than mine. I have a Grinch two sizes too small heart, because when I see a quote of mine, especially if it’s attributed to a white guy, I’m like, “Dude, you did not say that. Excuse me, I said that.” And I don’t even think “what serves the world the best?” I’m like, “No, sir, sit down. Sit down.”

SRT: “I need you give me my words back,” right? [chuckle]

BB: Yeah, no. Because attribution really matters.

SRT: It does. And I think that’s the, the dance. Is, attribution absolutely matters. And whose responsibility is it to correct the record? Because if I spent my life running around chasing…

BB: Oh God, that’s right.

SRT: Right? Chasing all the misattributed things, that would be, that’s what I’d spend my life doing.

BB: That’s right.

SRT: And what I loved in this moment that you shared in and you’re like, “And we’ve corrected it 10,000 times,” is, “Oh. What we want is for the place where the power and the resource and the privilege lies to also take on the responsibility of making sure that which should be made right, is made right.”

BB: That’s right.

SRT: And I really feel like you and your team have done that. And that’s been beautiful to watch.

BB: It’s been incredible too because what we do is we… We tweet it back with this… With the right, the same quote card but with your attribution, and then we have tracked what has been… We’ve done the A/B testing on what’s more effective.

SRT: Wow.

BB: And if we say… If we say, “These words belong to Sonya Renee Taylor. Can you help us?” People are like, “Oh, I’ll be glad to help. You’re right. I’ll be glad to help.” If we correct people, they get really self-righteous about it.

SRT: Defensive and like… Wow.

BB: But if we say, “We need your help because this is important.” People are like, “Right on. It’s important.” So, I just want to say thank you for sharing those words. I’m so glad it brought us together in this weird way.

SRT: Me too, and thank you for being a researcher who’s like, “You know what we’re going to do? We’re going to research that.”

[laughter]

BB: Yeah, no, I was like, “We’re going to look into how people are helping with this or not.”

SRT: I love it. Amazing.

BB: So, I’m going start with this book. Normally what I… I am always conscious like, “We don’t have that much time, get to the meat.” But I’ve got to start… I’ve got to start talking about this book. Again, The Body Is Not An Apology: The Power Of Radical Self-Love. I don’t like anything about this cover. It’s you being unapologetic with your body in this beautiful shot. I don’t like that.

[chuckle]

BB: I Don’t like you telling me not to apologize for my body, because I’ve spent my whole life doing that. And I don’t like the term “radical self-love”. So, it’s three strikes and I’ve got to read this shit right now.

[laughter]

SRT: I love it.

BB: Hard. But then I’m like, “I can do it, I can do it.” Then I actually read the prologue and had to walk away from the book for over a week. And you sent me this cryptic terrible message on Instagram. Do you remember it?

SRT: I did, I said, “I believe there’s something in it for your journey.” That’s what I said.

BB: That was mean, that was just mean spirited. Okay.

[chuckle]

SRT: I want you to know that it was abundant radical love that made me send that message. [chuckle]

BB: Yeah. See that doesn’t fool me anymore because I’ve read the book twice, and I know what you mean when you say, “radical love”, you’re not playing around.

[laughter]

BB: Okay. I want to take you to a hotel room. So, you’re in Knoxville is that right? Is that the right place?

SRT: Yes, yes. I’m in Knoxville.

BB: You’re in Knoxville. You’re in a hotel room, you’re with your team. Y’all are preparing for a poetry slam.

SRT: Yes, exactly.

BB: And you say, “We were Black, White, Southeast Asian, we were able-bodied and disabled. We were gay, straight, bi and queer. What we brought to Knoxville that year were the stories of living in our bodies in all of their complex tapestries.” So, you wind up in a conversation with your teammate, Natasha, an early 30-something, living with cerebral palsy and fearful that she might be pregnant. Natasha tells you how her potential pregnancy was most assuredly by a guy who was just a fling.

BB: And all of her life was up in the air for her, for Natasha. She was abundantly clear that she had no desire to have a baby, and not by this person. And so, somewhere in your career, many of the iterations, you were a sexual health and public health service provider. So, “this background”, you write…

BB: This is what you write, “This background made me notorious for asking people about their safer sex practices, handing out condoms, and offering sexual health harm reduction strategies. Instinctually, I asked Natasha why she had chosen not to use a condom with this casual sexual partner with whom she had no interest in procreating.”

BB: “Neither Natasha nor I knew that my honest question and her honest answer would be the catalyst for a movement. Natasha told me her truth: ‘My disability makes sex hard already with positioning and stuff. I just didn’t feel like it was okay to make a big deal about using condoms.’”

BB: You go on to say, “When we hear someone’s truth and it strikes some deep part of our humanity, our own hidden shames, it can be easy to recoil into silence. We struggle to hold the truths of others because we have so rarely had the experience of having our own truths held.” This really… This, “I didn’t feel like it was okay to make a big deal out of using condoms because my disability already makes sex hard.”

SRT: Yeah.

BB: This just pierced your heart. Tell me more.

SRT: Yeah. When she said it, it was this moment where, I often have these experiences… Let me not say often, but often enough, where my response is not a conscious response. It is not a, like, “Oh, I’m reflecting on what you shared with me and I’m sharing back with you.” It is something outside of me that needs to say a thing. That’s how it occurs to me. And so when she said that, what came out of my face just was, “Your body is not an apology.”

SRT: And I had never said those words. I’d never said them in that sentence, they had never been a thought I’d ever had before that moment. But there was something that needed us, not just Natasha, that needed me to know that there are ways that I had been giving myself away as a sorry for being in this body, for being this person.

SRT: And I could see my own being in Natasha’s moment there. And there was something that wanted both of us to interrupt that trajectory; there was something that wanted to halt that experience. And it broke my heart, and it’s one of those things where any time I tell the story, there’s an audible gasp in the room.

BB: Is there?

SRT: Every time. There’s never a time I’ve ever told that story and people do not go, “Oh!” Because there’s something so painful about thinking about this person not feeling entitled to their own safety, to their own sovereignty, entitled to their own pleasure in the way that they determine is best for them. And I think it’s not just, “Oh, that person. I see this moment as that person.”

SRT: There’s something in it, I deeply believe that when we hear it, we go, “I’ve done it. I’ve done that. I see myself in Natasha.” And that’s what happened in that moment in that hotel room, was I saw myself in Natasha, and there was something that wanted to halt that experience from continuing to replicate itself. And I really think that that’s how this entire movement, this work has spread, is because that thing wants to be halted and something new wants to get created.

BB: God, it was… It’s painful. It’s really painful. I mean, I wish I would have known that at 18 and 20, and I wish I would have known that, yes, the times I said yes when I meant no, but also the times I said no when I meant yes. Do you know what I mean?

SRT: Absolutely, yeah. The times when we just… The times when we don’t honor us, that’s really all it is, is like, “Oh, here are the ways in which I didn’t… Here are the ways in which I betrayed my own truth.” And in the intersection of your work is all of the shame that comes from betraying our own truth.

SRT: And so if there is a way of understanding our own bodies that can help us betray ourselves less, so that we don’t have to be mired in the shame of that betrayal, then yeah, what is that? Let’s do that. And I think, that’s what I think radical self-love is ultimately.

BB: Yeah. I’ve got to tell you, and we can talk about this later, that we’re going to go through some of the practical… Not practical. Revolutionary practices better than practical. Revolutionary practices, better than practical, because there’s nothing practical about anything in this. But I’m 54, and I’m trying to put these practices into my life, and you say, “Pick a mantra.” Like, “do you have a mantra?”

BB: And you know me like, I’m the effing Queen of mantras, man. I got mantras on vases, I got mantras. But I’ve never had a radical self-love mantra about my body before, and so I find myself really in this land of confusion around menopause and what happens in your 50s. And so again, feeling like now my body is a new apology, it’s still an apology, it’s just a new apology, but my mantra that I picked from you is, “My body is my ally.”

SRT: Yeah, yeah.

BB: And then I catch myself saying, “Hey Brené, your body is your ally and you’re engaged in performative allyship with your body.”

[laughter]

SRT: I love it. Merge the worlds, yes.

BB: Merge the worlds, yes, it’s crazy. Okay. So, here’s what you write, “At every turn for days after my conversation with Natasha, the words returned to me like some sort of cosmic boomerang. They kept echoing off the walls of all my hidden hurts. Every time I uttered a disparaging word about my dimple thighs, I’d hear, ‘Your body is not an apology, Sonya.’ Each time I marked some erroneous statement with, ‘My bad, I’m so stupid,’ my inner voice would retort, ‘Your body is not an apology.’”

BB: So I’m like, “Okay, I get it.” You’ve taken my breath away. I’ve had to walk away from the book and come back. I’ve thrown it across the room a couple of times.

SRT: I love it. I love…

BB: Which is…

SRT: I love that you’ve done all the things that I tell people they’re gonna do when they read the book. [laughter]

BB: Jeez Louise, yeah, it’s so hard. So then I get to this idea, and it’s interesting, of natural intelligence. So I’m like, okay, so you’ve got me kind of splayed open, and then I’m ready, I’m gonna build my self-confidence and I’m going to build my self-acceptance. Jesus, you’re like, “No.”

SRT: No. [chuckle]

BB: And you start with the story where you hear a quote from Marianne Williamson, “An acorn does not have to say, ‘I intend to become an oak tree.’ Natural intelligence intends that every living thing become the highest form of itself and designs us accordingly.” So what you’re positing in this book, I want to make sure I get this right, it’s so scary to me, is that I don’t have to strive for things and achieve more things and accumulate more things.

BB: I’ve got to get rid of the stuff that’s getting in my way, of tapping into my natural purpose and greatness. Is that what you’re telling us?

SRT: That’s exactly what I’m telling you. And I’m telling you that that will emerge, that, once we remove the obstructions that have us believe we have to try to become, we will just become exactly what it is that we are supposed to be. And that those obstructions are not just like our obstructions, that they are a world of obstructions that have been created, that are in between us and our inherent divinity, in between us and our innate enough-ness.

SRT: And the work of radical self-love is to keep moving the things that are in the way outside of me, and to keep working in concert with other human beings to move the things that are in the way in the world. And that when we do those two things simultaneously, when we do them together, I believe, and I may not ever live to see it, but I deeply believe that we make a different world.

BB: Okay. I want you to walk us through again, the two things that will come together to make the different world. Can you walk us through it one more time?

SRT: Yeah, absolutely. So, radical self-love is an internal journey that impacts our external reality.

BB: An internal journey inside of me.

SRT: It’s inside of you, and…

BB: But it impacts the world outside of me?

SRT: But it impacts the world. And the reason it impacts the world is because we are not living in a system of individualism. No matter how much our society would like to convince us that we are, the reality is that we are interdependent, that our experiences impact one another. You know when you’ve been in a conversation with someone and you leave it and you feel gross?

BB: Yes.

SRT: Like, “Eww. That did not feel good.” That is the impact of their internal story impacting you. And it can impact your whole day.

BB: That’s true.

SRT: Right? It can change the entire tapestry of the way you were moving through the day. So that’s just the energetic level. But the systemic and structural level is that we have built a world that is a reflection of our belief that we are not enough. We have built an entire system that then externalizes our value. My world, I will be good enough when I achieve dot, dot, dot.

SRT: I will be good enough if I have this job that pays me this amount of money. I will be good enough if I can hold tight to my identity as white, or able bodied, or cis, or all of these configurations of what I call the hierarchy of bodies, the world that we have assigned that says there is some top, and my job as a human is to figure out how to scramble to the top, how to try to get there.

SRT: Now, what’s true is, that we also recognize in this system, that there are some of us who will never get there. We have bodies that will never live at the top of that ladder. So what we spend our lives trying to do is figure out, well, what can I do? Well, I can lose 10 pounds here. I can affect my tone so that I sound more white. I can… There are all these things that we try to do. I can subscribe to rigid rules around gender, and I can do all of these things to try to understand my place in the hierarchy.

BB: So to climb up the caste ladder?

SRT: To climb up the ladder of bodily hierarchy. What radical self-love invites us to do is to divest from the ladder, to recognize that the ladder is only real because we keep trying to climb it, all of us collectively.

BB: Oh, wait. Say that again.

[chuckle]

BB: What radical self-love… Say that again.

SRT: Radical self-love invites us to divest from the ladder, because the ladder is only real because we keep trying to climb it, and when we stop trying to climb the ladder, then we have no more use for the ladder. When I don’t need the ladder to assess my sense of worthiness, of enoughness, of again, inherent divinity, when I don’t need that ladder, because I understand it as my birth right, I understand it as how I arrived on the planet, I understand it as my own unique form of natural intelligence, then the ladder is of no use.

SRT: The ladder is imaginary. The ladder is there to give me a thing that I was born with. So what do I need the ladder for? What do we need the ladder for, if we all understood that we already came here with everything we need in order to be all it is that we are destined to be?

BB: Let me ask you a question, I want to stay with your metaphor.

SRT: Yeah.

BB: I build a lot of ladders. I’m a ladder builder. Yeah, especially my…

[overlapping conversation]

BB: Yeah, my academic training really is like ladder building 101. Okay. So that ladder that’s leaning against the system, right, that I’m not gonna climb up, that I’ve got everything here, what happens to the system when the ladder goes away?

SRT: The ladder isn’t leaning against the system; the ladder is the system.

BB: Holy shit. Hold on, let me pull myself together here.

[laughter]

SRT: The ladder isn’t leaning against the system; the ladder is the system. It is all the things that we have built to figure out how to attain the top rung. It’s all the systems, all of them. And it’s all of our place on there, inside of them. That is what the ladder is. And so once we undo it, we don’t have… The system, the system falls. It literally…

SRT: One of the most powerful things right now today, as we are recording this, the NBA has said, “We’re not playing. We are not playing because we are not going to continue to play basketball while Black people are being murdered.” If every single NBA player decided, “We are not playing basketball as long as Black people are being murdered,” the entire system that is the NBA would collapse. Immediately.

SRT: Immediately, it would fall. They would not have the infrastructure to figure out how to hire new players fast enough. Not in COVID, right? There would be nothing but the collapse of that structure as we understand it, simply by the choice not to participate in it anymore. That material example is an opportunity through… And it does… And again, I’m talking about it, it is not simple. It’s not easy. I think it is simple. It is simple. They’re just like, “We’re not playing.” [chuckle]

BB: No, it’s simple.

SRT: “We’re not playing.”

BB: It’s actually super simple, and that’s the complexity of it.

SRT: It’s super simple.

BB: Yeah.

SRT: It is. It’s super simple. “We’re not playing.” Okay, what happens when we say we’re not playing? The entire system falls. That’s what happen.

BB: I read the statistic… This takes me back to something that was like… So I had not thought about this for, I don’t know, since 9/11. So I started my research like six months before 9/11, so I’ve really been able to watch how fear has changed us. And I remember reading an article comparing the cosmetic and diet industry to the airline industry, what it experienced after 9/11.

BB: And the article said something like, if every woman woke up and said, “I love what I see, I’m not buying anything,” it would be a faster collapse than the airlines after 9/11. It would be within 24 hours, the entire system. So, we are the ladder, like our shame is the ladder.

SRT: We are the ladder; it is the ladder.

BB: Our shame is the ladder.

SRT: And if we divest from it, we would collapse all the systems that are built on it.

BB: Man, this is… Okay, so this is helpful because now I understand. There was a part of this book that I fell so in love, so in love with you. I’ll tell you it has to do with pot pies but…

[laughter]

BB: Because I grew up on pot pies for sure.

SRT: Yes, yes.

BB: Did you grow up on pot pies?

SRT: Yeah, I hated them. I told… Well, I didn’t hate them, I told you the part I hated, I hated the mixed veggies inside the pot pies. I liked the crust and I liked the chicken and the gravy.

BB: Okay, so here’s what you say. So you’re asking the… You say to the reader, okay, “Well, if this book is not going to help me with my self-esteem or self-confidence…” Because you say self-esteem and self-confidence, this is way deeper than that. That stuff is fleeting. Right?

SRT: Yep, yep. It’s shaky ground.

BB: Shaky ground, right. “Will it at least help me with self-acceptance?” Can I read what you wrote here?

SRT: Yes, please.

BB: Is it weird when I’m reading your stuff?

SRT: No, it’s a delight. [chuckle]

BB: Okay. “My short answer is, if I do my job correctly, no. This book is not going to help you with self-acceptance. Not because self-acceptance isn’t useful, but because I believe there is a port far beyond the island of self-acceptance, and I want us to go there. Think back to all the times you accepted something and found it completely un-aspiring.”

BB: “When I was a kid, my mother would make my brother and me frozen pot pies for dinner. It was the meal for the day she did not feel like cooking. I enjoyed the flaky pastry crust, the chunks of mechanically pressed chicken in a band-aid colored beige gravy, were tolerable.” [chuckle]

BB: “But there was nothing less appetizing than the abhorrent vegetable medley of peas, green beans and carrots portioned throughout each bite like miserable stars in an endless galaxy. Yes, I ate those hateful mixed vegetables, hunger will make you accept things. I accepted that my options were limited: pick out a million tiny peas, or get a job at the ripe age of 10 and figure out how to feed myself.”

BB: “Why am I talking about pot pies? Because self-acceptance is the mixed veggie pot pie of radical self-love. It will keep you alive when the options are sparse. But is there life beyond frozen pot pies?”

SRT: Yes.

[laughter]

BB: Oh my God. I want everybody listening right now, just to raise their right hand, like in honor of Sonya, if you’ve had the band-aid colored medley. Yes.

SRT: Yes. If you’ve had your chicken pot pie frozen. [chuckle]

BB: Yeah, you say that self-acceptance is used as a synonym for acquiescence.

SRT: Yeah, yeah.

BB: You’re not interested in self-acceptance?

SRT: I don’t want to be accepted. I want to be loved. If you have the choice between love or acceptance, which would you pick?

BB: Oh, love.

SRT: You’d pick love. Love is richer, it’s warmer, it’s… Love does something.

BB: Oh yeah.

SRT: “Acceptance” is an innate word. It is an inert word, it does not do anything, it stops there.

BB: No, it just kind of lays there.

SRT: Yeah, it just lays there. I accept that. There’s nothing, literally. There’s nothing… It is a passive term. “Love” is an active term, it is a thing that makes you get up and do something, to change something, to shift. It creates its own momentum. I want for the world a love that changes shit, that’s what I want. I want us to love in a way that disrupts, that destroys the ladder. Acceptance won’t get us there.

BB: Man, it’s this… I’m going, I’m going… I’ve had a couple of conversations recently where I just land in the soft gritty, toughness of bell hooks and lovelessness. Acceptance is not the answer to lovelessness.

SRT: It is not. It’s not. It doesn’t get us where we need to go. And in a world that is structured in the way that this… This world is not structured like, “We’re indifferent towards you.” If the world were indifferent towards us, then acceptance might be alright. Okay, well, “I’d like you to not be indifferent.” “Cool, I accept you.” We live in a world that is structured in so many ways on hatred.

BB: Oh God, that’s true.

SRT: On a hatred of ourselves, on a hatred of the other, on a deep sense of lack and disconnection. We need something so much more magnanimous, more powerful, to shift that experience, than acceptance.

[music]

BB: Okay. So far, I’m with you.

SRT: Okay.

BB: My body is not an apology; my body is my ally. I’m with you, and I’m gonna stay away from performative allyship. But you see performative allyship with our bodies, all the time over social, right?

SRT: There is an entire… I think that that’s actually much of what body positivity is right now, is performative allyship with our bodies.

BB: Yeah, I’m not in for it. Okay. So I agree that I do think… And I even, I’m not actually a fan in my research of self-esteem and those things, because they’re fleeting, they’re shaky, and they’re cognitive inventories, they’re not real deep stuff. I’m with you so far.

SRT: Yeah.

BB: I’m gonna embrace radical self-love. It scares the crap out of me, but I’m gonna do it.

SRT: Got it.

BB: Man, you posit something in this book that is very provocative, that I have not seen any other place. And I’m a voracious reader around shame.

SRT: Okay.

BB: You tie body radical love to social justice, and body shame to injustice and violence and white supremacy and oppression. So, I need you to… I’m going to invite you, I don’t need you. I do actually, actually, I’m going to go back to I need you. I will.

SRT: Okay, okay.

BB: I need you to help me.

SRT: Yeah, definitely.

BB: Okay.

SRT: So I’m gonna go back to our ladder.

BB: Okay.

SRT: Because that’s, I think that that’s really what helps us, right? Is, if we have all been situated on a ladder of hierarchy, that some bodies are better than other bodies. Right?

BB: Yes.

SRT: That’s the premise. In the world, there are some bodies that are better than other bodies.

BB: Can I ask a question here?

SRT: Absolutely.

BB: Does the some bodies are better than other bodies, extend all the way to the dehumanization of Black bodies by the police? Is that, when you say “some bodies”, you’re not talking about thin or tall. You’re talking about…

SRT: And that’s exactly… That’s the problem, is that we have these very limited understandings of the body. And because we have such a limited understanding of the body, it makes it difficult to see all the places where our relationships with bodies are impacting the systemic violences that we’re looking at in the world.

BB: Okay.

SRT: The part… In a world where there’s a default body, I talk about this in the book, there is a body that we say is the best body by default. Because it’s the body that we ascribe as human. When they wrote the Constitution, they said all men were created equal. They meant men, they did mean men, which is the reason why they excluded all other bodies.

SRT: Because in their vision, who deserved to have equity, who deserved to have equality and life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness and justice, were white men. White, land-owning men. That became the default body of value in the society, and all other bodies got situated somewhere on the ladder of hierarchy, in terms of whether or not they were ever going to be valuable in the world, from an externalized position of value.

SRT: Because again, white and male are not externalized, those are birth. That’s identities that we give… Assign at birth. Land owning is external, and land owning is the way, is the caveat that was given to ensure that not everybody got to be at the top. Because the system requires scarcity, that system demands that everybody can’t have access to it. Because if everybody has access to it, then I’m not as special as I thought I was.

BB: Too much shared power.

SRT: Exactly. Then now I’ve got to, “Wait a minute. Now I have to figure out how everybody gets?” No, everybody can’t get. So here’s who can. Right? Then we constructed a government based off of that. We constructed a policing system based off of that. We constructed an economy based off of that. We constructed a school system, based off of that.

SRT: We have constructed the systems and structures of this society based off of that default body. And then we needed, when other bodies have attempted to disrupt the ladder, to disrupt that hierarchy and threaten that default body as the top position, we are not gentle in the way in which we control that ladder.

BB: No.

SRT: Society is not gentle…

BB: No no.

SRT: In the way in which it controls that ladder. This society, and the structures therein, will resort to murder to control that ladder. And that has always been the case.

BB: Yeah, because it’s effective because it creates collective trauma to the entire…

SRT: Exactly.

BB: Group of similar bodies, so you only have to do it…

SRT: Exactly.

BB: So often to remind people that that’s a reality.

SRT: This is what it is.

BB: Yeah.

SRT: This is what it is, right? And so simultaneously using both violence as a way to control the ladder, and reinforcing narrative of you will never be at the top because you are inherently not good enough to be. And so, that is how you end up with systems and structures like white supremacy and the agents therein.

SRT: The policing system in the United States was initially created as roving agents to collect runaway slaves, that was the inception point of that sort of structure. I’m a firm believer that we cannot think that we’re going to magically change a structure that was born to do a very specific thing.

SRT: And so the system, when we’re talking about what’s the connection between radical self-love and social justice, is that that system was created from a disconnection of radical self-love. It was, I need external orientations to assign my value, and then once I’ve achieved that value externally, then I will move Heaven and Earth and all of you other people in order to continue to control that, because who am I without it? Who are we without it?

BB: God it’s like I have goosebumps because I’m thinking about Isabel Wilkerson’s book, Caste, and I’m thinking about how people went to court and filed suits wanting to be identified on paper as White, like Asian-Americans or…

SRT: White, yeah.

BB: So that they could find their place in the ladder.

SRT: It is the whole policing of whiteness in America, has been about trying to attain some closer proximity on the ladder. It is the structure of colorism within communities of color. It’s about, “How do I get higher up on this ladder?” The function of ableism is about, “How do I get higher on this ladder?”

SRT: All of our systems of isms, of oppressions based on the body, are attempts to navigate the ladder of social hierarchy based on our bodies. And those systems that live within that ladder are the systems that we’re talking about fighting when we’re talking about social justice.

BB: I think the power of your premise and what you write about is powerful, because it’s the one thing we all have.

SRT: Everybody. You can’t do this ride without us. [chuckle] You might be doing a different ride.

BB: It’s like you say the word “everybody”, but it’s every body.

SRT: Every body, everybody. And so if we recognize that we all have a body, it really is the opportunity to make it the great equalizer. It is the opportunity to say, “But we all are interfacing.” We all have to interface with this thing in order to be in this material realm, doing whatever it is we’re doing. So, is it possible to have a wrong version of this to do that, to live? Is it possible to have a wrong version of a body to do the human experience? To be true to that?

BB: I mean, the answer to that would be yes. The answer would be we’ve set it up to believe yes, but how could it be true? That can’t be true.

SRT: It can’t be true, because if that were true, then those body… Then other bodies wouldn’t exist. If we believe Marianne Williamson’s premise about natural intelligence, then human bodily diversity is a form of natural intelligence. It means that all bodies are supposed to be different because that is the version that is specific for your particular journey.

SRT: And now what’s interesting is we believe that in so many other areas of the natural world, and we don’t believe it in the human world, and that’s the thing I find fascinating. We believe it about trees, we believe it about dogs, and cows, and grasses, the variety and nuance of all of those things. We expect there to be millions of different kinds of trees. There are all kinds of different manifestations. I have… When I moved to New Zealand, I saw a chart of cows. Now, in my brain it’s just a cow.

BB: Right.

SRT: There are like 45 different kinds of cows.

[laughter]

SRT: All different. And nobody’s like, “It’s a hierarchy of cows.” No one’s ever said there is… [chuckle]

BB: No. And in fact, we honor that. In fact, I have friends that pride themselves on, “There are 47 mushrooms and 34 of them are in this thing I made.” We love that.

SRT: It’s not even just that we love it, we know that it is necessary…

BB: It’s true.

SRT: In order to have a thriving world, a thriving ecosystem that works in harmony, we need variance. We recognize that. We know that innately. And yet, because we are so far away from our own sense of inherent knowing of our enoughness, we’ve constructed a world where that’s not true for our bodies.

BB: You know, I gotta… You write this. You said, “Moving from body shame to radical self-love is a road of inquiry and insight. We will need to ask ourselves tough questions from a place of grace and grounding.” And Jesus, do you ask tough questions in these little call-out boxes that make it very difficult to skip them, even though I did try my best.

[chuckle]

BB: Let me ask you this question. I got to find in my note here, because this is… This was a tweet today. And I won’t say who it’s from. It’s from I think a public official type person, a journalist maybe.

SRT: Okay.

BB: This is the quote. “Ideologies, racism, Nazism, don’t die even when defeated in war, or legislated against. But they are sufficiently shamed, so that those who hold such views are not given platforms in politics or media. We need more shame. The election is about whether we can return shame to the nation.”

SRT: Nope. Yeah, complete and total shame. Miss. [chuckle]

BB: Yeah, I mean I look at… We are drowning in shame.

SRT: Drowning in it.

BB: It’s like, you know when people do that scary thing, if you’re listening right now, where they put their hand right over their lip and they say the water’s here? The water’s over our nose with shame.

SRT: It’s… Yeah, yeah.

BB: We don’t need more.

SRT: We don’t. The problem is that, that person, that tweet, is actually interested in maintaining the ladder.

BB: Okay, stop.

SRT: They’re just like, “No. Well, actually what we need is we just want the ladder to look a little better.” It’s not, “Oh, this entire system is built on this ladder.” There’s a way in which they believe, I think in similar to the question that you said, which is, okay, so we get rid of the ladder, the building is still there. Let’s just figure out how we can get rid of the ladder. And until they realize that the ladder is the system, that shame is the source of how the ladder got built.

BB: Yes.

SRT: That the structure that they would like us to revert to is actually the structure that more firmly ensconces the experience of a disconnection of radical self-love. And that will work. I don’t know who this person is, I don’t know their identity. My hunch is they might be a little higher up on the ladder.

BB: White female.

SRT: And so it is useful for them to imagine a world where that ladder just feels less shaky. That’s really what it is. But for all the people that live in identities below where they are placed on that ladder, the thing that they think is going away, like, “Oh, we just shame people, and then it goes in the quiet,” has never… That has not stopped police murders of Black people’s bodies. It has not stopped deportations. It has not stopped any of those things. What it has done is, is it made it less visible to you, person higher up on the ladder.

BB: Not you, the mother of the Black son that’s killed.

SRT: Exactly. And so what she’s really asking for is a world where I don’t have to be as impacted by all the things that have been happening. That’s the world I want. I want it to go back to quiet enough that I can ignore it.

BB: You’re asking something so revolutionary of us, because what you’re saying… What I hear you saying, and check me on this, is the ladder of systemic oppression and hierarchies is built on our self-hate, and our self-loathing, and our shame. And the only way…

SRT: Yeah.

BB: We are that system, and the only way we dismantle that system is radical self-love for ourselves and other people. Is that what you’re saying?

SRT: I am saying that the only way to dismantle the ladder in the world, is to dismantle the ladder inside of ourselves.

BB: Okay, let’s move on, ecause you got some practices for us. Okay, let me… I’ve got so many, if you’re listening, you should see.

[chuckle]

BB: Okay, talk to me about the three peaces.

SRT: Yeah.

BB: And when we say peaces, we’re P-E-A-C-E, like peace.

SRT: Yes, yes. Like peace, not like a three-piece. I mean, if it needs to be like a three piece of chicken to better orient this stuff, make it a three-piece. However you want to have it. [chuckle]

BB: A breast and two wings would be my thing.

SRT: See, I’m a two thighs and a leg girl.

BB: Okay, got it.

SRT: Yeah.

BB: We can split a chicken real good. [chuckle]

SRT: We would be hooked up, we would be hooked up, Brené. So the three peaces are, I believe the foundation of how we begin a radical self-love journey. So they will not… They are what’s the orientation that I need to take in order to start on this road. And they are: make peace, with not… This may not be in the order in the book, because I don’t always remember.

BB: It’s okay.

SRT: But it’s, make peace with not understanding. Make peace with difference. Actually, I think make peace with difference is first. Make peace with not understanding. And then, make peace with your own body. That those are the three foundational things you’ve got to grapple with in order to even begin this inquiry.

SRT: Because if you still see difference as bad, then all the ways in which you are different will always be bad, and all the ways that the rest of the world is different, will always be bad. Then we will always be back in the hierarchy, we will always be back on that ladder where I’m trying to get out of my bad body into some better body. Or I’m always trying to assess whether or not my body is bad in comparison to the bodies of others.

BB: God, that’s hard. I’m a pretty self-evolved person, honestly I am, and that is hard.

SRT: The challenge… Here’s the thing for me, the trick has been, I recognize that every time I’m in that space of comparison, I am the cog holding up oppression.

BB: I’m gonna start doing that. I’m acting like the ladder right now.

SRT: I’m the ladder right now. I am the ladder right now. I am the ladder. Because as long as my value is dependent on someone’s greater or lesser value, then it demands a world where there are people that are less valuable than me.

BB: Can I ask you a really hard question?

SRT: I like those.

BB: You do?

SRT: Might have a terrible answer, but I’ll try. [chuckle]

BB: Okay. So I’m reading these and I’m like, make peace with not understanding, tough for me, but I’m getting… That’s tied to my spirituality for me personally.

SRT: Yeah, absolutely.

BB: Yeah.

SRT: Absolutely, me too. Yeah, I’m like, “Oh my God, I can’t… ”

BB: Right.

SRT: “I can’t know what God knows.”

BB: Right. Make peace with your body, I’m really working on that. It just keeps changing so much and so fast that I’ve got to do a deeper peace that is transcendent of the changes, you know what I mean? It’s hard. Make peace with difference. Okay, let me tell you, on the face of that, I thought to myself, “Make peace with different bodies, I think I have that.” But let me tell you where I struggle, and I’m prepared for this to be a hard learning for me, so you just bring it, you bring it.

SRT: Okay. [chuckle]

BB: So there have been a couple of times on public media, once a couple of years ago, when everyone in our office decided that we were going to do a healthy January, and all 27 of us were going to cook and bring meals for each other. And we were going to do like a… It was really community building and fun, it was a Tupperware nightmare, but we were gonna do this thing.

BB: And I was cooking something from, I think a Whole30 cookbook, and someone said, “Oh my God, you’re doing Whole30? You’re a terrible person for doing that, and you shouldn’t be doing the Whole30.” And then the other day, I talked about how for years and years, I’ve been keto, because that’s just how I feel good, and then people are like, “You’re a terrible person.”

BB: I push up against sometimes… I know how I feel good. I know that if I walk five days a week, I know that if I eat certain foods, I feel like crap. I know that if I carb load, I can’t get out of bed in the morning, I get headaches. But it seems like, I struggle sometimes when people say to me, “When you are making choices for yourself that you have checked that are not part of body conformity, you’re hurting other people.”

SRT: Yeah.

BB: I don’t know what to do with that. Is it just that I’m blind to the fact that I bought into something? Or is it that we… I don’t know what to do.

SRT: Yeah. I feel like… It is complex, and I think that it’s one that I have grappled with, and other people have shared this question with me in different forms over the years. And I think that it’s a both/and. And it’s a very, it’s nuanced. What I think is true is that we, absolutely, it is important for us to know that which is true for our bodies, that which feels true to us. And that there will be times when what feels true to us potentially reaffirms a system that is harmful in the larger world to other people’s bodies.

BB: I think that’s true.

SRT: And that there is a delicate navigation between those two things. One of the things that I, I don’t even know if I said it in the book, but I say it all the time, is that it’s almost less about what we do and almost always about why we do it. And if we can be in the why, then the what becomes a lot more easy to navigate.

SRT: The Whole30, the keto, these sorts of things… Well, first of all, I would say that anybody starting the conversation with, “You’re a terrible person,” is definitely not starting the conversation from a position that is a radical self-love position. Because the radical self-love position says, “I’m not even… It’s not about your Whole30, it’s not about your keto, it’s about the why.”

SRT: And I think that this is the part where the “how many layers am I willing to keep pulling back?” Because if my why is I feel better, my why is I feel better in my body, this absolutely helps me. And the what, which is the specific form, the name of the thing, whatever, is harmful, then can I get to my why in a way that doesn’t have to engage the what that is harmful?

BB: Oh, great question, yes.

SRT: Right. And because if I can do that, then I can be in the authenticity of what is true for me, and also be mitigating the harm that is caused. But there are lots of things that I think are good ideas on the surface, but they have created a system of harm, inadvertently. They didn’t necessarily mean to, but they end up being part of a mechanism that reaffirms the ladder.

BB: Yes.

SRT: And so, how do I get in touch with my why and then make my why align with the way that I get there? That’s the work. So absolutely, if recognizing carb loading is going to make you barely be able to get out of the bed, then definitely don’t carb load, that wouldn’t be a radical self-love action, right? But does not doing that need to be ascribed to this particular thing that also has, that is part of a larger system that reaffirms harm?

SRT: That’s the dance. And it’s a complex one. It is not an… It is a complex one and it is an internal one, because it requires us to really be with the why. I’m going take it outside of the… Out of the conversation.

BB: Yeah. I mean, I’m really tracking that why/what question is super profound. It’s like why I can’t follow a whole bunch of the accounts that have great recipes for the way I eat, because our what is very similar, but our whys become very dangerous for me.

SRT: Why is real different.

BB: Yeah the whys are dangerous.

SRT: Exactly.

BB: Like I don’t do scales, I don’t do sizes, I just do feel good and be able to move.

SRT: Yeah, exactly. And I think that… And so again, learning, well, what’s the language that better aligns my why with the way I want to have the world experience, or the people who might be harmed by a certain system, to experience it? I believe that we can find a way to make our why harmonize with the world we want. I believe we can.

SRT: It takes introspection, it takes really digging into my why. And then it takes saying, “Okay, so here’s this… There are things about this that work.” I can do those things without ascribing to that system. Because that system has all the other stuff that comes along with it too, and I don’t want those parts. So here’s the things that I do take that are useful for me.

BB: And God, this is so incredible because I think about all the exercise equipment that I’ve used over the years, up until like two weeks ago, that I use basically to dry my clothes on. Yeah.

[chuckle]

BB: But my what was something that for a lot of people is great, it feels wonderful, they’re moving their bodies. For me, everything that drove that was a super destructive, a super destructive why. Like I’m just a walker, that’s it. I can’t do anything else fancy. Like that’s it.

BB: And so I get the what and the why, and I think, I usually don’t talk, these are not subjects I take on as subjects. Like, “Let’s have a podcast on low carb.” I’ll just mention it in something. But I can see now how without context it can be a scary what for people without the why.

SRT: Yeah, absolutely. And that the why gives us context for ourselves, it gives us context in the world, and it helps us decide what is the what that lines up best.

BB: Yeah.

SRT: With the why. What is the one thing… You got to it. You were like, “My why is I want to move my body and feel good. And my what is walking. Because when I buy a bunch of fancy gym equipment it changes my why.” My why now is like, because that’s what I should do because I’m not… Whatever the why becomes.

BB: Because everybody’s doing it.

SRT: Because everybody’s doing it. Because everybody’s doing it. So lining up our why and our what, is how we get to the radical self-love motive inside of us.

BB: Oooh, I love that.

SRT: And how do we live that motive externally.

BB: Say it again.

SRT: Yeah. So lining up the what and the why… I never had to practice so hard remembering the thing I just said.

[chuckle]

SRT: Lining up the what and the why, is how we align our radical self-love motive.

BB: God it’s so good. Okay, I want to talk about these four pillars of practice because they’ve been so helpful for me. Can we talk about them?

SRT: Yeah, absolutely.

BB: Okay. The four pillars of practice. This is… Let me just read a little bit of the intro, if that’s okay. “We know that adopting a radical self-love lifestyle is a process of thinking, doing and being.” And for me it’s like, “Oh my God, unlearning. So much painful unlearning.”

BB: “But changing the way we think, act in our daily lives can feel like an assignment of planetary proportions. So the four pillars of practice can help us corral our wily thinking, fortify love laden action… ” You’re such a poet. “And give us access to a new way of being in the world. The pillars are: Taking out the toxic, mind matters, unapologetic action, and collective compassion.” Give me a little overview of what taking out the toxic means?

SRT: Yeah. So… And it really does do with this sort of thinking part of how do we move into a radical self-love way of being in the world. Every day we are surrounded with all kinds of messages that reinforce the ladder. The whole point is keep the ladder in its place, please.

SRT: And we’ve been in it for such a long time that we’re oblivious to it. Like it just, it runs like static in the back of our lives, but it’s not in the back of our lives, it’s actually in us. And it’s in the way that we think, it’s in the decisions we make, the things we watch, we listen to, what we eat, what we won’t eat, the machines we buy or don’t buy. It lives in us.

SRT: What taking out the toxic does is it first asks us to raise to consciousness the messages that we’re getting. So that they’re not just like background noise, but that we recognize them. “Oh, this is the fifth commercial I have seen telling me to buy extreme trim.” Or whatever. Whatever that is.

BB: Oh yeah.

SRT: This is the… This the… I watch this… I think about it even when I watch the news now. I’m like, “There is nothing but the how many people are dead or how many people are about to die.” That is all that I have watched for the last 20 minutes. I see that. I see that as information about what it is that I am taking in. Once that’s at a conscious awareness, then we actually have some choice. You can’t make any choices until you’re actually at a conscious awareness.

SRT: And so it’s like, “Oh, I get to say how much toxicity I want to take in or not.” Some of it I don’t have any choice about, I live in a world. But there are some things I don’t have to do anymore. And so one of the things that I really started doing was I started noticing back in 2012 when they had the whole, “The world’s gonna end on December 21st of 2012.”

SRT: And I have heinous apocalyptic anxiety, or at least I used to. Really extreme apocalyptic anxiety. But I also was very compelled to keep watching things that fueled it. And so I’d be watching, “The seven ways the world might end. The… ” [chuckle] Just every horrible, dark show, all the time.

SRT: And I was like, “Sonya, notice what this does to you. Stop. Just for today.” And don’t… I’m not gonna will myself to stop forever. For the next 48 hours, I’m going to not watch this, and I’m gonna notice what that does to my body. I’m gonna notice how my anxiety drops two notches. I’m gonna notice how the sort of compulsive thoughts subside. I’m gonna notice that I have more space.

SRT: “Oh, I have more space. What would I like to be doing that doesn’t help the anxiety ratchet back up, or doesn’t help the compulsive thoughts come back? Oh, maybe I want to write a poem, maybe I want to make a dinner tonight. Maybe I want to go hang out with friends.”

SRT: All of a sudden, I open up the space to try something new where that toxic thing was. So taking out the toxic is an opportunity to first inventory how much toxic stuff we’re taking in, and then to create a space where we block that from constantly coming in, and then we begin to think about what would we like to fill it with.

BB: I had a therapist tell me probably seven or eight years ago, “I can’t and won’t continue to work with you if you keep consuming so much news, because we cannot undo the trauma in an hour a week that you’re taking in 20 hours a week.” And I just…

SRT: Absolutely.

BB: Yeah, I just stopped. And my life changed. And until this very moment, I knew that the anxiety stopped and the having violent images on loop stopped, but what I didn’t know until right this minute is the… I didn’t have the word to say that an expansiveness came into my life, that I was able to fill with nurturing things.

SRT: Exactly, exactly. And if we don’t have the space. Right now, it’s like we’re in such a constant loop of it that we can’t even see a way out of it, and so part of what taking out the toxic does is it actually reminds us that we have some efficacy.

BB: Yes.

SRT: We have some efficacy over this dynamic. Some of it we cannot do anything about, but what we can have in our purview, let’s go on ahead and try to do something with that, and then see what wants to emerge in that vacant yet fecund space.

BB: I love that. Okay, mind matters.

SRT: Yes. So now that we’ve gotten… We’ve inventoried this toxic stuff we’re taking in, we’ve got this expansive space, what do we do with it? What do we want to put in our brains that is different than the toxic stuff that we were taking out? And that requires us to get in touch with the way we’ve been thinking.

SRT: Because now that we don’t have this constant input all day, we actually are left with, “Oh, here’s the stuff that’s just inside my own head. Okay, what is that? And what is it that I can do? What practices can I take to shift perspective, to shift the angle from which I’m looking at a thing so that I see it as possibility rather than detriment? So I see it as a thing I can move toward rather than a thing that is hindering me.” That is perspective shift, and perspective shift is easier to do when we are not inundated with all the other toxic outside messages.

BB: That’s right.

SRT: Again, it was your therapist saying, “I can’t even deal with the real stuff, because every day we’ve got to process… ”

BB: The trauma.

SRT: Right, the trauma of the last news cycle. So let’s remove that so that we can actually get to the others, the narratives that are far longer running, that desire to be shifted.

BB: Yeah, and I’ve got to say that I do not think that a system… I think the news cycle, the cable news cycle is a part of the ladder. Totally…

SRT: Absolutely.

BB: Yeah, totally connected to money and advertising. And not… Consuming that in massive amounts, is not an act of radical self-love, in my opinion.

SRT: It can’t be, it can’t be, because there isn’t anything in it that is nurturing.

BB: No.

SRT: That’s really the answer. If it isn’t nourishing, it’s not radical self-love.

BB: Amen.

SRT: And so I’m pretty certain that anything that constantly makes you feel enraged, fearful, anxious…

BB: Blaming.

SRT: Blaming, disoriented, is not a radical self-love engagement. It’s not. It can’t be.

BB: Okay. Unapologetic Action.

SRT: Yes. So now you’ve got the space, you’ve tackled some of this stuff that’s in your brain, you’ve shifted your perspective. Now it’s time to do something. Because… And I think that this is a really important moment in our own history where we get to be in that reflection. A lot of people are coming to this moment of like, “Oh, we’re in these systems, these systems are harmful. Oh no. Let me learn all the things. I want to read all the books.”

SRT: I’m like, “That’s all I want you to do. Read the books.” But if you’re not prepared to do anything, the ladder will stay as it is. You can know the ladder, you can see the ladder, and if you’re not interested in dismantling it through action, then you’re actually not of any assistance to certainly the larger structure of creating a radical self-love world.

SRT: And so, unapologetic action is like, “What can I do today in a way that is… ” I do use the word “practical”. “That is practical?” But I like “revolutionary” better.

[laughter]

BB: But if you do it, it’s actually… It’s practical, but if you actually act on it and do it, it’s revolutionary.

SRT: And that’s what I love about it. It’s like, “Oh, I actually have the ability in my everyday life to do something that is utterly transformative.”

BB: That’s right.

SRT: “But doesn’t necessarily seem like it is.” And so what is that? What is that? That is taking an old story that I’ve been in forever and figuring out what actually is my access to personal power in that and retelling the story that way, is that I would like to move my body, but I don’t want it to be married to these old, just like body shaming, vicious ways of understanding my relationship to my body.

SRT: Oh, well, what are things I can do that do feel affirming, nourishing, nurturing? And like, what were some of the other tools that are in mind, are in unapologetic action?

BB: One of the things you write about in unapologetic action, which is like, pleasure.

SRT: Pleasure, pleasure.

BB: That’s revolutionary, and that’s scary as shit for people.

SRT: Pleasure is revolutionary. There’s a great book by a friend of mine, Adrienne Maree Brown, called, Pleasure Activism. And it is about, what does it mean to find pleasure as an access to changing the world? And pleasure and radical self-love go together. They are peanut butter and jelly.

BB: That’s right.

SRT: And so what is it that you can do in your own life… Howard Thurman, who was a 19th century theologian, says, “Don’t ask the world what to do and go do that. Ask what makes you come alive, and go do that. Because what the world needs are people who have come alive.” What pleasure invites us to is, what makes us come alive in our bodies? What makes us light up? What makes us activate? Because in that activation, is the ability, is the stamina to change the world.

BB: That’s right.

SRT: Yeah. Without it we don’t have the stamina.

BB: No, and it plugs us back in, it energizes us and it gives us something to live and love for.

SRT: Yes.

BB: That’s hard. Pleasure’s hard.

SRT: Yes, pleasure is.

BB: Like, let’s just say we got a lot of shame around pleasure.

SRT: We got… I was going to say, we have so much shame stuff about pleasure. And if… But again, if we can change our mind matters, right? If that which is nourishing, nurturing and fulfilling is an act of radical self-love, then that which brings me genuine pleasure is an act of radical self-love. So then the question is, “Oh, shame becomes the obstruction that the ladder has put in place to keep me on the ladder.” That’s the trick, it’s to keep seeing where the system is trying to get you to reinvest in the system.

BB: It’s really smart. Okay, last one, collective compassion.

SRT: Yes. That, we need each other. We need each other. This is, again, this entire dance we’re on is a dance about trying to one-up each other. So we already know we need each other, the problem is right now we’re needing each other in a system of comparison and lesser than and greater than, rather than a system of harmony.

SRT: This work is impossible to do alone. And I think it’s one of the things that’s the scariest things for folks, is because they’re like, “You want me to take all this shame, all this discomfort, all this… You want me to go be in community?” And yes, the answer is to be in community, that the entire structure requires, it’s sustained by you being the host of the disease. And when you stop being the host of the disease, the disease actually can’t continue to fester, it doesn’t grow. And so…

BB: There’s no conduit. Yeah.

SRT: There’s no conduit, right? And in the book, I talk about the epidemiological triad, which was one of my… I was saying, “I’m a scientist for one day.”

[laughter]

BB: I loved it.

SRT: But it’s, right… But it’s… We break one of the vectors of how this thing keeps moving in the world. Community is how we do that. And isolation and individualism is how we build a whole system. Because the system is collective. Be clear, the system has a…

BB: Right.

SRT: The structure is collective, it is an entire system meant to direct how you operate. If you think you alone are gonna beat that whole system, you’ll be right back to all the awful feelings you were having just last week. Right? But in community, you, one, get to have reflected back to you your true self from people who see you.

SRT: And collectively you will get to remind yourself that they’re… That that outside voice, that whole mechanism out there isn’t the truth. You need a reflection of the truth in order to keep moving in the truth. Otherwise, it starts to get fuzzy.

BB: It’s shaky, it becomes wobbly.

SRT: It becomes… The system’s designed to gaslight you.

BB: Yeah.

SRT: It’s designed to tell you the thing you know you don’t really know. That’s not true. It is true that you’re not good enough, it is true that you need to lose 15 pounds, it is true that you’re actually just never going to be pretty as a Black, dark skinned girl, Sonya. That is true. The system needs me to believe that. Community is where I get to constantly have that disrupted. So we need community.

BB: We got it. We need each other.

SRT: We need each other. We need each other.

BB: Okay, before we get to the 10 speed questions, the speed round, I want to close with this quote from you. It’s on your last page of the book, “Liberation is the opportunity for every human, no matter their body, to have unobstructed access to their highest self, for every human to live in radical self-love.”

SRT: Yeah. Yeah. Yeah, that’s the world I want. If there was nothing that ever obstructed any oak tree, we would just have glorious forests of vibrancy. They would… That’s what I want…

BB: And difference.

SRT: And difference.

BB: Yes.

SRT: And variety. They’d be different heights, they’d be different shapes, they would… And they would all be working… What am I thinking right now? There’s a root system underneath them, that talks to each other, and it’s how they all keep standing and growing. That’s the world I want.

BB: Connected, yes.

SRT: It’s the world that’s already available to us. It’s the world we started with, in some ways. And what if we could bring all that we have learned back to all that already was in the beginning? What might that be?

BB: Oh my God.

SRT: That’s what I want to go to. That’s what I want to go to.

BB: I’m going with you.

SRT: Yay, let’s go. Let’s go together. [chuckle]

BB: I’m in. Oh, and we’ll get… We’ll talk about the playlist on our way there, because you gave… Okay, so you ready for the 10 rapid fire?

SRT: Yes, lightning.

BB: Vulnerability is?

SRT: Scary.

BB: You’re called to be brave, but your fear is real, and you can feel it right in your throat. What’s the very first thing you do?

SRT: Pray.

BB: Something that people often get wrong about you?

SRT: That I’m never afraid.

BB: Okay. Last show that you binged and loved?

SRT: Last show that I binged and loved? Insecure.

BB: Oh God, Issa Rae is so good.

[chuckle]

SRT: Issa Rae is so good.

BB: Okay. One of your favorite movies?

SRT: My favorite movie, number one, period. Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory.

BB: Original or new?

SRT: It’s sacrilege to speak of anything other than the great Gene Wilder.

[laughter]

SRT: It’s sacrilege. Almost a sacrilege. The original.

BB: I’m with you, I’m with you, okay.

[laughter]

BB: Okay. A concert you’ll never forget?

SRT: Prince, in Oakland, California at the Coliseum. The best master class in artistry. Masterful. The best thing I’ve ever saw.

BB: Favorite meal?

SRT: Candied yams, macaroni and cheese. My momma’s fried chicken.

BB: Can your mom cook for our journey? If we’re going to go to this place together, can she… [chuckle]

SRT: She’d be happy to give us her heavenly recipe, that I believe that she would… She’d figure a way to transmit it. [chuckle]

BB: Oh, okay. Yes.

SRT: Yeah.

BB: We can act on that.

SRT: We can. We can. We can. I believe that my mother often has bequeathed me in her passing with her recipes. And so when I’m really, really patient and I ask, she will walk me through it. So yes, I think we could still do it.

BB: Dang. I would just clear my mind just for those to have a way to get to me, actually.

[chuckle]

BB: Okay, what’s on your nightstand?

SRT: Oh my goodness. Right now… Well so, this isn’t my permanent nightstand. What’s on it or in it? These are different questions. [chuckle]

BB: On it. I don’t go in it, baby. I don’t go in it.

[laughter]

SRT: Good job. Good job. There’s a rose water candle. There is a book on angels. And a lamp. And usually the earrings I had on that day.

BB: A snapshot of an ordinary moment in your life that brings you true joy?

SRT: In my pajamas, in my night gown, sitting in a big comfy chair, watching the river out the window.

BB: What are you deeply grateful for right this minute?

SRT: This conversation with you. This opportunity to be in this conversation with you.

BB: Me to. Okay, you shared a playlist with us. So, how do you say, “Hezekiah?” Am I saying that right?

SRT: Hezekiah Walker. Yes, Hezekiah Walker. [chuckle]

BB: I just started sobbing when I listened to that song.

SRT: I was gonna say, did you listen to these? Like, yes. It is when I need to just… When I need to be in the devotion to the I Am. To that which I say, made trees and bees and honey and fleas, and also decided that there should be a Sonya Renee Taylor. That, when I just need to be in overwhelming reverence to that, that’s the song I listen to.

BB: So, “Turning Around For Me”, VaShawn Mitchell, your overcome song.

SRT: Yes, yes.

BB: “Let’s Chill, by Guy.” Your 8th grade crush song. I love that.

SRT: Yes. [chuckle]

BB: “I Still Haven’t Found What I’m Looking For”, by U2, which is your endless nostalgia song, and mine too. We can listen to that on cassette on our drive.

SRT: Absolutely. Yes, yes.

BB: And then, I forgot about this song until I saw it in your playlist and it just crushed me. “Love You To the Letter”, by Anita Baker.

SRT: Yes. First of all, the Compositions album is by far my favorite Anita Baker album. And that song is just… Uh, it’s so good. [chuckle] It’s so, so good.

BB: “Like water flows down from a hill and yellow grows on daffodils, I’m gonna learn to love you better, baby to the letter.”

SRT: Oh, it’s so good. It’s so good. I’m like, yeah love me like that, please. To the letter. [chuckle]

BB: Yeah, love me like that. And let me love me like that.

SRT: And let’s love ourselves like that. Yes. Yes. Let’s love ourselves like that.

BB: Thank you so much for joining us on Unlocking Us.

SRT: Oh my gosh, it has been an absolute delight. Like one of the highlights of my existence, Brené Brown, is to get to have this conversation with you.

[music]

BB: I hope this conversation unlocked some things for you, because I can guarantee you that it unlocked some stuff for me, including, my body is my ally, my body is my ally, my body is my ally. I’m gonna keep saying that until I really get it. Follow Sonya Renee Taylor everywhere. At Sonya Renee Taylor on Instagram. Also @the body is not an apology. Twitter is @radical body love. She’s got a Patreon account at www.patreon.com/Sonya Renee Taylor.

BB: The book again, is, The Body is Not An Apology: The Power of Radical Self-love. You can get it anywhere you get books. I read it in one sitting the first time, and I read it slower the second time, because the first time I read it fast because I was trying to dodge stuff.

BB: Also, I wanted to thank you before I sign off today for all the support around the 10th anniversary edition of The Gifts of Imperfection. Again, the book that gave birth to this community. I will always be grateful for that and for all of you. Thank you for listening to Unlocking Us. Until next time, awkward, brave and kind.

[music]

© 2020 Brené Brown Education and Research Group, LLC. All rights reserved.