Brené Brown: Hi, everyone. I’m Brené Brown, and this is Unlocking Us. Ooh-wee, that’s all I’ve got to say. This podcast gets very personal, very fast. What do you do when you have Dr. John Gottman and Dr. Julie Gottman on your podcast, and you’re looking at them on Zoom and you’re coming off of the most difficult season of a 30-plus year relationship? You’re going to ask some hard questions. And let me tell you, they’ve got answers. They’re just not what you always want to hear. They’re just what you need to hear. Drs. Julie and John Gottman talked to us about relationships, partnerships, couplehood—they’re the experts. They have 40 years of breakthrough research on marital stability and divorce prediction, and they connect that data to practical teachings about conflict resolution and creating connection. They demonstrate how science can help people have successful loving relationships. It’s incredible. One of the things that just really stands out for me about their work, especially as a social scientist, is that in their research they can tell within the first three minutes of a couple’s interaction the longevity of a relationship or the health of a relationship. They can do this within 90% accuracy.

BB: Basically, they can watch you get in a fight with your partner and within the first three minutes predict whether you stay together or you don’t. The work is incredible. And it’s not about tips and tricks, either. It’s really about this foundational friendship that has to be partnerships, appreciation, and respect. We talk about the toll the pandemic has taken on couples, we talk about their research, and we talk about very practical shifts that can help us take care of each other. I think the information changes the way I think about myself, and it has changed the way I’m showing up with Steve. I’m working on it, because it’s important to me. There’s probably nothing in the world more important, and it’s hard. So I’m so glad you’re here with us today. This is one hell of a conversation.

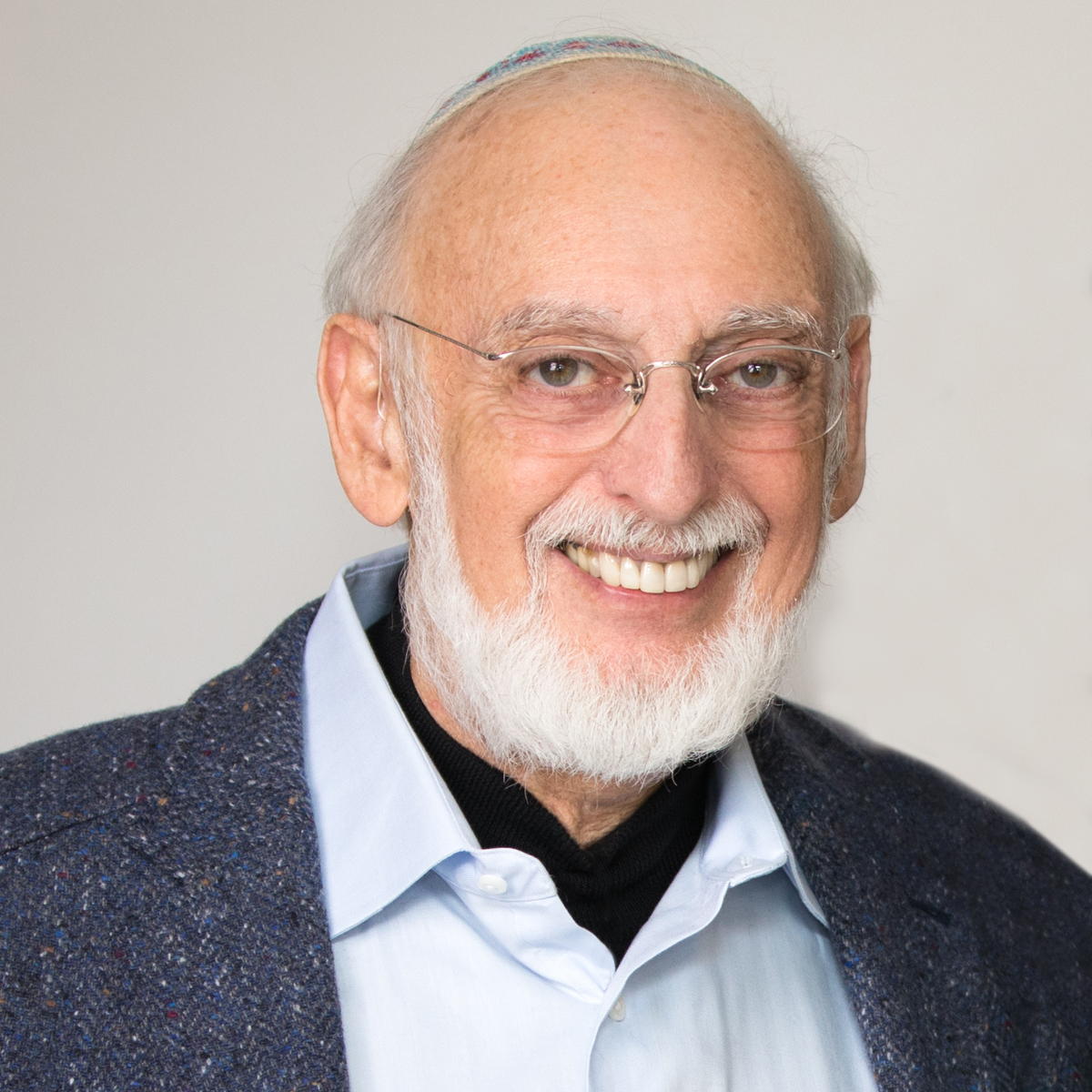

BB: Dr. John Gottman, world-renowned for his work on marital stability and divorce prediction, has conducted over 40 years of breakthrough research with thousands of couples. He is the author of over 200 published academic articles,and the author or co-author of more than 40 books, including the New York Times bestseller The Seven Principles for Making Marriage Work, What Makes Love Last?, The Relationship Cure, Why Marriages Succeed or Fail, and Raising an Emotionally Intelligent Child. Dr. Julie Gottman is a highly respected clinical psychologist whose expertise on marriage, domestic violence, gay and lesbian adoption, same-sex marriage, and parenting issues is highly sought after around the world. She is the co-creator of the immensely popular the Art and Science of Love weekend workshop for couples and co-designer of the national clinical training program in the Gottman Method Couples Therapy.

BB: Julie is author and co-author of six books, including 10 Lessons to Transform Your Marriage, And Baby Makes Three, 10 Principles for Doing Effective Couples Therapy, The Man’s Guide to Women, and The Marriage Clinic Casebook. The Gottmans’ most recent book together is—I love this book, y’all. It’s called Eight Dates: Essential Conversations for a Lifetime of Love. Together, John and Julie co-founded the Gottman Institute, an internationally renowned organization dedicated to combining wisdom from research and practice to support and strengthen marriages and relationships by offering workshops and resources for couples, families, and professionals. They recently, and this is really interesting to me—they recently co-founded Affective Software, with the goal of delivering proven relationship couples assessment methods and interventions to the broadest reach of people across race, religion, class, culture, sexual orientation, and ethnicity. The new Gottman Love Lab will combine Gottman Method science with cutting-edge expertise in software, AI, and machine learning.

BB: They’re also offering the Gottman Relationship Coach online program, where the Gottmans have taken their research-based skills and communication tools and put them together with new content for a series of video programs that you can work through at your own pace. The Drs. Gottman, y’all. This is a big episode. I have to start by saying, I’m a little nervous and I’m always anticipatory and excited, but this crosses over into—I’m kind of nervous to talk to y’all.

Julie Gottman: Brené, that makes no sense whatsoever, because we are the ones who are nervous. And we only have one cerebral cortex between the two of us, so I have half, he has half. And so if I’m nervous, then he suffers.

BB: You’ve just been, both of you, North Stars, giants in the field. It’s so funny, because whether I’m talking to 10,000 nurses or I am working with a group of Fortune 50 leaders, I say “The Gottmans” and everyone’s like, “Yes, the Gottmans.” I want to start with something personal. Tell me your love story. Yes, tell me how, where, when you met. I want to know your love story.

Julie Gottman: All right, I’ll begin. I had just finished my Ph.D. at the ripe old age of 35. I was divorced for about six years. I wanted to get out of Southern California, so I said a prayer, jumped into my packed car, drove north, had my car stolen and then returned in San Francisco, decided San Francisco wouldn’t be the place to be. And so kept going north to Seattle. Then I decided, “I should probably have some woman friends first before dating anybody.” So this is in 1986. So I made a couple of friends at work, working as a therapist, and then I was walking into a coffee house about six months later and there was this cool guy that looked like a Bolshevik, which to this Jewish heart is like love at first sight. He was wearing these really cool shaded sunglasses, and he had on a black fisherman’s cap and a black leather coat—

BB: Oh God.

Julie Gottman: And I was stunned with love. [Chuckle] And so I just stood there, and I was going to a party with my mother, and John came over to me and he asked me if he could buy me a cup of coffee. And I said, “Oh yeah.” And so we sat there and talked, and it was immediate, immediate connection. And, Brené, I will only tell you this, that when he turned around to pay the bill, I looked at the back of him, and I’m one of those many, many millions of people that have little visions every now and then, and I had had a vision two years earlier about who I would end up together with as my lifelong partner, and when I looked at the back of him, it was exactly the photograph in my head that I’d seen two years earlier. Then I thought, “Oh my God, I’m really in trouble now.” And so five months later he proposed.

BB: OK. I have goose bumps, first of all, and I totally have those visions, and I believe in them. OK, so you’re a smoking-hot Bolshevik at the coffee shop, John—

John Gottman: Well, my story is that I was starting a job as a professor at the University of Washington, and school started in October, so I arrived in Seattle in May. And I also had been divorced, for about seven years, and lived in a college town in Illinois, Champaign, Illinois, and couldn’t meet any women my own age. So I was in my 40s, and so I decided I was going to answer every ad in the personal column of this magazine, and so I actually thought, “Why not deal with this dating thing like it was a job?” And had a database of women in Seattle, and so I went on 60 dates before this moment in the coffee shop.

BB: Oh my God.

John Gottman: I answered every ad. So Julie was number 61, and when I met her—and it was very clear from our first conversation that she was a real outlier for me. She was really very, very different. She was easy to talk to. She was beautiful to me, to my eyes, has always been. And from the first date in a place called the Pony Expresso

John Gottman: We both really fell in love with that first conversation.

BB: So you pay for the coffee, she sees the back of you, it’s an exact image of her vision, and—

John Gottman: I don’t know that.

BB: Right, you don’t know it at this point, but do you exchange numbers? Do you agree to see each other again?

John Gottman: Yes. Yeah, she walked me to my car, and she said that seeing my car was the first time she really felt the pangs of love.

Julie Gottman: [Laughter] So can I tell you about his car? His car is the greatest car. So his car was voted the ugliest car in the University of Washington faculty parking lot, which is really a large place. And I totally loved it. It was—

John Gottman: And what did you call it?

Julie Gottman: I called it Bondo. Do you know what Bondo is, Brené?

BB: You mean like car Bondo?

Julie Gottman: Yeah, like car Bondo.

BB: Yeah, of course. Yeah.

Julie Gottman: Yeah, well I didn’t, because I grew up in the Northwest. I lived in California. Nothing rusts over here. It just gets moldy. And so John in Illinois had had this red—what was it?

John Gottman: Dodge.

Julie Gottman: It was a red Dodge. It was really old. It had a Naugahyde bench front seat. I guess some really cool guy had come to John’s neighborhood in Illinois and said, “Do you want me to repair all the holes in your car?” which had been caused by the rust in the winter in Illinois. He said, “Yeah, of course.” So he slapped these white patches of Bondo all over the red car. Well, the car never got painted, so—

BB: Oh God.

Julie Gottman: So it looked like a pinto car. You know what a pinto is? It’s a type of horse that’s black-and-white.

BB: Of course.

Julie Gottman: Of course, there it was.

John Gottman: So Bondo held my car together, but it ran really well.

BB: Oh my God.

John Gottman: So why get rid of it, right?

BB: Why get rid of it? Yeah, because I can see the whole story now, because you salt the snow, the salt gets in the car, it rusts the car, you put the Bondo on—I totally get it. And so six months of dating, you propose, and y’all have been together for how long now? What’s the math?

John Gottman: Thirty-five years we’ve been together.

Julie Gottman: Right. And wait, you have to hear the proposal. The proposal was perfect. So I knew by then, five months later, what John did. I’d never heard of him before that because my work had been only with individuals, not with couples, doing deep, deep, deep trauma work and stuff with individuals. So we’re sitting at a Chinese restaurant after going to synagogue for Shabbat, for our Sabbath morning, and we’re sitting across from each other and he looks at me and he says, “What do you think about the idea of marriage?” And I thought, “So what is this? Is this like a research question? Is he asking me about something having to do with his work? What is this?” And I said, “What do you mean, marriage?” And he said, “You know, you, me, marriage.” I said, “Oh, is this a proposal?” He said, “Yes.” “Oh, well let me think about it.” So I thought about 45 seconds and then I said, “OK,” and that was it. That was the end.

BB: OK, that’s so funny, because I’ve never heard another person reflect back to me the weirdness that happens in my house sometimes when I will say to Steve—I just recently did it, like last week, I said, “Tell me about anguish.” And he said, “I’m frustrated, I’m in a bad mood, but I’m certainly—I wouldn’t describe what I’m feeling as anguish.” I’m like, “No, no, no. It’s a research thing I’m working on, a research question. From your experience as a physician, when you’ve seen—” And he’s like, “OK, you need to tell me upfront whether we’re talking about your work or our life.” And so I love this. I love this. Tell me, John, what you were thinking of when you framed it that way?

John Gottman: I don’t think there was a lot of thinking in it. It was just a moment of terror.

BB: Did you feel vulnerable?

John Gottman: Oh sure, yeah. I wasn’t sure what she’d say.

BB: You weren’t?

John Gottman: No.

Julie Gottman: Of course I’d say yes. Of course I would.

John Gottman: OK.

BB: For that of y’all who can’t see the Zoom, they’re making out now. OK. That is just the best story. It’s not the story of, like, you walk out to the park and you’re like, “Oh, so that’s what you drive? Like are you going to get—” It wasn’t that. It was like, “Oh my God, this just seals the deal for me with this guy.”

Julie Gottman: Exactly.

BB: Was it a slow evolution? I don’t like the word “empire” because it has all this capitalistic terrible connotation maybe, but you have built an empire of love and good health and kindness, and did you set out to do that intentionally as a couple, or did it just evolve over time, where your work started lacing and weaving? Like how did that happen?

Julie Gottman: First of all, for the first nine years of our marriage, I tried desperately to keep my work life separate from John’s, because I was going to have my own identity and my own private practice, etcetera. But every night, we talked about John’s research and what he was finding in the lab, and it was so fascinating to me that I couldn’t help myself. There was a gravitational pull. So one day—this is how it began—we were sitting in a canoe out in the sea, the Pacific Ocean, and I said, “What do you think? How about if we use all your research to help people? You know what successful couples do. You know what mistakes couples make. So maybe we can help change marriages from disasters to masters.” Now he is the one who thought of those words, not me—the “master/disaster”—but it seemed like a great idea. And then John also had been invited—was that to the University of Chicago?

John Gottman: Northwestern University.

Julie Gottman: Oh, to Northwestern. OK. Yeah, they had offered him this magnificent job with a full chair, full honors, tons of research, didn’t they?

BB: Oh wow.

Julie Gottman: Yeah. Well, we had a problem, which was that I hated flat land.

John Gottman: She’s a mountain girl.

Julie Gottman: I am.

BB: She’s a mountain girl, and Northwestern is not a mountain town.

John Gottman: That’s right. I love the city of Chicago, so it was a very attractive offer, and my mother had recently moved to Seattle, and she said, “I’m not moving again,” and so I turned down the job and I was kind of sad about it because it was a great offer, and then in this canoe we decided whatever I could build in Chicago we’d build it in Seattle together. And Julie had been very involved in the design of my apartment lab at the University of Washington—that got dubbed “the Love Lab”—where we saw 130 newlywed couples a couple of months after their wedding and followed them, as many of them became pregnant, and learned how to study them with their babies, and videotape their interaction with their 3-month-old babies, and kept following the couples and the babies. And so she’d been very active in that, in designing the lab. So it was a natural. And her experience as a clinician was essential in everything we built, because I was really reluctant to try to help couples because Bob Levenson and I—and Bob and I had done all this research together for 25 years. He’s really my brother in doing the research.

John Gottman: So it started with a bromance and then continued adding this romance. And Julie’s clinical experience was absolutely essential in really formulating this theory—the Sound Relationship House theory—that we created together. And in going back to the lab and checking things out and creating a theory that was testable and disconfirmable, where we could measure everything in our theory and try to help therapists be able to measure everything in their offices, to evaluate the strengths and challenges any couple has.

Julie Gottman: So what we did is we worked on interventions together, after creating the theory, and then John would go and test the interventions. We had to make sure that what we were offering to couples made sense, but one of the reasons we knew it probably would make sense, these interventions would work, is that they were not based on John and me. They were based on the thousands of couples that had gone through the lab and had with their great generosity and heart shown us what they did year after year after year to sustain their relationships. Then we joined with a woman that we met, named Etana Kunovsky, and Etana was a brilliant, wonderful partner who helped establish our program development. So it was the three of us at first, and then a couple more people later on, and we’d meet around our dining room table once a week and we would plan what we wanted to offer couples and clinicians. And then we developed a clinical training program. That took off. Etana helped us expand from the ground up, to really build the institute. And years and years later—so this is now, what, 25 years ago—then her husband took over, Alan Kunovsky, as CEO, and he’s an incredible businessman, just brilliant.

Julie Gottman: He built the staff to about 35 people, and we basically stepped back, showed up when and where they told us to show up, gave little talks and trainings and things, and the rest is history. I never, ever had the dream that the institute would become as well-known as it has, and I think that 100% the work really is the responsibility and to the credit of the staff that have worked with us, to the people who represented our programs, to the ones who graphically designed them, and without them I’d probably still be sitting in a little chair. And actually, oh my God, Etana planted her foot in my back, because I had total fear of speaking in public. So she pushed me literally out onto the stage in order to talk. And I said a little prayer and said, “OK, help me, because I have no idea of how to talk to people,” and then I did get help. And that happened, I don’t know, 15 years ago, maybe?

John Gottman: Mm-hmm.

Julie Gottman: Yeah. So we built from there.

BB: John, how does what you’ve built, what you’ve scaled—what’s so important and enduring about it is researched, evidence-based, empirically based interventions—and very few people in the world have pulled this off—that are democratized, they’re accessible, people understand what you’re talking about, and then have been built into programs and scaled. How does this fit with any dream that you ever had for your work?

John Gottman: Well, this really is my dream, that science can really help people to understand how to have a loving relationship, because we know that from a lot of empirical research that having a successful, loving relationship confers 15 years longer of life. It confers health, resilience, and children thrive within that loving relationship. So it makes people healthier, wealthier, and it’s the secret to longevity, at this point in medical science. So it’s something that Bob Levenson and I only dreamed about. And to create the interventions really required not just the research but the intuition of a clinician who really understood the kind of pain that people are in and could help them with all kinds of other things that they brought into a relationship, the trauma of childhood that they endured, and made this really work. It was really the combination of a scientist and a clinician that made this work.

BB: Unstoppable.

John Gottman: Without Julie we would never have happened.

BB: You can feel the heart prints and fingerprints of research and clinical work all over everything you do. It’s so beautiful. OK.

John Gottman: Thank you.

BB: So I’m going to jump in to some questions about your work. I want to get into some specifics. I want to talk about Eight Dates. I want to talk about, always, of course, the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, always, because you can’t get it enough, but I want to start by asking this: This past year has been a painful, painful season for many. I will tell you just honestly, because I’ve talked about it before, Steve and I have been together for 30 years—the most difficult season of our marriage. What are you seeing in the pandemic, the overdue reckoning around racial inequality, everything coming to a head—what toll, or if any, do you see this taking on couples?

Julie Gottman: Brené, it’s a wonderful question, one that we sadly answer. We are seeing terrible stress between people. We are seeing relationships that may have functioned fairly well because both individuals were really involved in the world in their own separate ways. Now they’re trapped within a space, right? And sometimes in certain places that space is one room, if they just have a studio apartment. Not everybody can afford a house, etcetera. So people are losing jobs. People are losing people. People are at wits’ end trying to sustain connection with one another, and they’re not able to do that, not in a way that feels fulfilling. There’s a huge difference between a two-dimensional screen that we look into and the energy of a being in front of us and touching that person, holding that person, really looking into their eyes, which we can barely do on our screens. So we are seeing more domestic violence, much more domestic violence.

BB: Oh God yes.

Julie Gottman: Much more hostility. Right? We are seeing much more criticism. The phrase “people getting on each other’s nerves” doesn’t match it. It’s people getting on each other’s souls in a negative way, people beginning to see everything that’s wrong with their partner rather than what’s right with their partner. And as a result, the tension, the distance for many couples, is growing by leaps and bounds. However, there are some couples who are actually using this time together, which maybe they haven’t had with their 17 children at home, to really build closer connection, more bridges, deeper conversations that can really help to flower their relationship, to help it bloom. They’re far and few between, but we’re seeing couples like that too, and what that has led us to do is to create yet another wave of help, basically in a software platform that couples can use at home with one another that gives them exercises and tools to do, with videotapes of John and I—

BB: Interesting.

Julie Gottman: In order to get help without having to walk out of their house.

John Gottman: On their phones.

Julie Gottman: Right.

BB: Oh man, I’m a social worker, so the axiom of meeting people where they are—which is we’re on screens and phones right now at home—so it’s helpful and feels normalizing to me to hear that we’re not alone in this kind of coupledom pandemic struggle. And I will say that, yeah, the domestic violence thing, that’s an issue. It’s been very important to me since early in my career when I did some work in domestic violence, and not everyone that has to stay at home is safe at home. And it’s a crisis inside of a crisis for sure. I want to see if we can talk about the Four Horsemen and their antidotes in a context of the pandemic. Talk to me about how these four danger areas—what would you call them? Like four—

John Gottman: Almost like fault lines that are there for a potential earthquake. So if they’re in a relationship, they spell potential disaster. So the pandemic would be like an earthquake, and the Four Horsemen are the fault lines that lie under the surface.

BB: Beautiful, beautiful. So criticism, contempt, defensiveness, and stonewalling, these are big flags for you, right? For both of you.

John Gottman: Yeah, if I can just say a word about that.

BB: Please.

John Gottman: Where relationship science is the weakest is in trying to predict whether two strangers will like each other and hit it off. There’s nothing we can measure that really allows us to do that prediction, and people have tried all kinds of things: preferences, interests, common values, philosophies, even asking people what they want and matching that. Nothing works, but we do know that people are not looking for their clone. Similarity is not the basis of attraction. So we want something really interesting and different from who we are, and the real problem that people get into when they form a relationship is then trying to turn that other person into them and—

BB: Painful.

John Gottman: And thinking, “I’m perfect, but you’re inadequate because you’re not like me.”

BB: Painful.

John Gottman: And so criticism is what emerges. And so the disaster couples in the lab Bob and I created are pointing their fingers at their partner and saying, “As far as I can tell I’m pretty much perfect, but you’re defective. Here’s what’s wrong with you.” And they list all these characteristics that they want their partner to change. And they’re hoping that their partner will respond by saying, “Oh, John, you’re so intelligent and sensitive. Tell me more about how I can change to make you happy.”

BB: Yes.

John Gottman: And instead, they get defensiveness, and the partner saying, “You’re not so perfect, either. Here’s what’s wrong with you,” and so they’re off and running, whereas the masters really point their finger at themselves and say, “Here’s what I’m feeling and here’s what I need from you,” and it’s not easy to—

BB: Nope. That’s too hard.

John Gottman: Yeah.

BB: That’s harder.

John Gottman: OK.

Julie Gottman: It is harder.

BB: Tell me, so the masters point their finger and instead of saying, “Here’s what I need you to change,” they point their finger to themselves, and what do they say again?

Julie Gottman: Here’s what they say. They say something like, “I’m upset that the kitchen is a mess. Would you please clean it up?” Now, that may sound, like, tricky. It sounds like jargon. It sounds phony. But it only sounds that way when you first begin to do it. The reason is that anything that we do for the first time isn’t going to feel natural to us. It takes practice and repetition, like 10,000 times, right, for something to feel natural. But once you really work hard at using that kind of language, “I feel something”—so I’m upset, angry, sad, afraid, tense, anxious, happy, whatever. About what? Describe the situation, not the character flaw of your partner. About a dent in the car, about the bills not being paid, about the kitchen a mess, about the dog not being walked—you describe the situation and then say a positive need. Now, what’s a positive need? A positive need is what you do want, as opposed to what you don’t want. What you do want in order for your partner to shine for you. So it’s going to sound like, “Would you please clean up the kitchen?” “Would you please drive slowly next time?” “Would you please take our puppy out for a walk?” The positive need.

John Gottman: But all of that takes place within the context of shared humor, accepting your partner as they are, reassuring them that everything is OK. So the masters are doing a lot more because they’re friends, because they’re close to each other, and because they built something together. They built a life together that has meaning and purpose and adventure and play, and all of these wonderful things. That gentle startup happens within a context of shared humor, of being able to laugh at yourself, of affection, friendship, and love, and having built a life together that has purpose and meaning, and with playing and adventure and all kinds of wonderful things sustained in the relationship. So in other words, that simple skill doesn’t work by itself. It works within the context of the fact that this couple has not ignored the relationship. They’re affectionate. They tell each other “I love you” every day and mean it. They stay friends. They keep playing together. They keep having adventure or learning together. There’s a lot of connection. It’s not just what they do during conflict. That’s why we need the whole Sound Relationship House and its weight-bearing walls of trust and commitment within which all of this works.

BB: God, that makes sense. So it’s not a bag of four tricks. The foundation is deep friendship and appreciation for each other. I have to tell you that I am so stuck on this moment. I can tell y’all, if you’re listening to this podcast, what we’ll be exerting is this whole idea that I did not want to marry someone like me, and that I’m most critical about the things that I loved in the beginning that are different from me, but when I’m scared and stressed out and fearful, I need another me for some terrible reason, I don’t know why. But it’s funny, when I talk to my 15-year-old and my 21-year-old about their relationships and what they’re going to let slide and what feels like a deal breaker for them, and they’re like, “Well, you and dad have gotten in arguments and been frustrated with each other for a long time before,” and I can never explain, “But we have a 30-year-old house that is filled with like—we laugh at each other’s jokes more than any other two people in the world.” And so this idea of understanding—we need to watch criticism, we need to meet it with a gentle startup, we need to watch contempt and meet that with a culture of appreciation, but you’re not tips and tricks. You’re doing something deeper, right?

Julie Gottman: That’s right. For example, one of the things that we really saw in the master couples, too, is that they asked each other open-ended questions all the time. “Why is this so important to you?” “Help me understand what this need means to you.” “Where does this come from in your history?” “Is there a dream you have beneath this position you have on this issue?” So they were plumbing the depths of each other, to understand each other better and better as human beings. One of the things that I absolutely adore about your work, Brené, is the concept, of course, of vulnerability, which is at the heart of this, literally. And what that means is people knowing each other at a soul-deep level, at a heart-deep level. And in order to know one another as human beings who are flawed, imperfect, selfish sometimes, greedy sometimes, inconsiderate, thoughtless, whatever—all those self-criticisms we give ourselves, right? Well, all of that is part of being human. And we need to feel accepted as human beings by our partner.

John Gottman: And cherished.

Julie Gottman: And cherished. So not idealized, not seen as this perfect—I don’t know what—competent, creative, nurturing, fabulous human being, but as somebody who makes mistakes, and we make mistakes every day, and the acceptance of that, of our deeper humanity, is what builds a deeper friendship. It’s that recognition that nobody is perfect, least of all ourselves. And we can’t expect our partners to be perfect or fit some soulmate ideal, but instead they’re just a person who typically is doing the best they can, and if we ask those big questions of “Help me understand why you said that. What was going on for you? What got triggered for you there?” then we can understand each other and accept each other for the history we have, the pain we’ve gone through, maybe even the abuse we’ve gone through, the highs and lows we’ve gone through, and see each other in the context of our deeper humanity, not as some figure on a pedestal.

BB: I just have to say that the cherishing of the messy, imperfect human person is hard when we’re scared.

[Music]

BB: The Four Horsemen: criticism, contempt, defensiveness, and stonewalling—these are predictor variables. Is that fair, John?

John Gottman: Right.

BB: Tell me how they work as predictor variables.

John Gottman: So it turns out that if you take a look at how couples just talk about how their day went, you can get predictor variables that allow you to predict the emergence of the Four Horsemen. Just the way their friendship is, and it’s really the lack of interest in one another that when couples are talking about how their day went that predicts how they deal with a conflict. So if there’s not a basis of continued interest and curiosity in one another, if they’re not nurturing that friendship and that emotional connection, then these Four Horsemen emerge, and you can see it so easily in our observers, who are trained to look at the videotapes and score how many seconds of contempt were there, how many seconds of criticism were there, how many seconds of defensiveness and stonewalling were there to get numbers. Those numbers predict the future of a relationship. They predict it with over 90% accuracy, in study after study. And it’s true for gay and lesbian couples as well, and couples at every stage in the life course—predicts how they will adjust to becoming parents, what kind of parents they’ll be, how they’ll deal with retirement and their later life. These predictors are very powerful.

John Gottman: And there’s another thing there that we didn’t anticipate initially, that Bob and I discovered only later: The devitalized marriage doesn’t have the Four Horsemen. It just has no interest in one another. So there are marriages that divorce later, not 5.6 years after the wedding, but 16.5 years after the wedding, when their kids are teenagers usually. The devitalized couple—that’s been called the sexless marriage; The Sex-Starved Marriage, by Michele Weiner-Davis—that kind of couple also is in trouble, and they don’t have the Four Horsemen. What they have is a lack of passion and curiosity about one another. They’ve let their friendships die, and they’re in trouble too.

BB: That statistic around looking at criticism, contempt, defensiveness, and stonewalling and being able to predict within 90% accuracy the longevity of a relationship, or the health of a relationship, is pretty staggering, wouldn’t you say?

John Gottman: Yeah. Well, we were really—Bob and I were totally floored by it, because most psychological studies have correlations that are 0.3 around, and they account for 9% of the variation. We were accounting for over 90% of the variation, so it was surprising to us as well.

BB: So when I look at these—isn’t it incredible to have given birth and then even more life, for both of you, to something—I mean, this changes the world. This information changes the way we love each other and think about ourselves. It’s so crazy. And when I think about the pandemic, I think about—just like everyone, I personally have to watch the Four Horsemen, but during the pandemic I’m more critical because I’m scared, and I don’t know why Steve doesn’t have all the answers to everything. I’m in more contempt because every decision I make for my children feels like a life-or-death decision. I am defensive because when I make the best decision I can with the information we have and it doesn’t go well, I feel like the stakes are so high because of the pandemic. And then the stonewalling is just—I don’t have the bandwidth. I don’t have the bandwidth right now. And so I can see how this idea that this earthquake has come—and it’s not just the pandemic, and it’s not just the racial reckoning, it’s also—and I’m just going to say it—four years of an administration that felt loveless.

John Gottman: Right.

BB: Persistent dehumanization of people. You wrote something that I have underlined 25 times.

Julie Gottman: Brené, can I respond to your comments?

BB: Yes, please.

Julie Gottman: Thinking about fear and how fear manifests—what are we most afraid of? Well, part of what we’re most afraid of is what’s unpredictable and what’s out of our control. And as a result, how do we compensate for feeling out of control and helpless and powerless, which the pandemic has made us feel, racial violence has made us feel, four years of the last administration has made us feel that every single day, that we’re under attack, that all of our values are under attack, are being misrepresented, and we’ve had no way of changing what is out of our control. So ever seen a cat who’s cornered? What does it do? It’s terrified, but what does it do? It claws out. It claws at whatever comes near it.

BB: Yeah, it pounces.

Julie Gottman: Because it feels so out of control and threatened. I think all of us are feeling that way, and as a result, we’re becoming over controlling to try and have control over what is in our little tiny hovel. What’s in our neighborhood? Let’s try and control at least that. That’s where the criticism comes in. When we can’t control that and our partner, by golly, they have their own brain and their own ideas about what they want to do, we escalate to contempt, looking down our nose, which is even more of an aggression on our partners to, again, try to get them under our control so we don’t have to feel everything is out of control, including our relationship. So you’re absolutely right. You’re spot-on. John and I certainly have some of that too, where if things are out of control, like the technology question—I call myself “TI,” technically impaired—and he knows more than I do about almost everything, including technology. So what that means is “I’m having trouble. It’s his responsibility to fix it,” and if he wants to do something else, holy cow, the roof blows off the house. So feeling afraid, feeling out of control, is very much within all of us, and we’re having these negative reactions to it.

BB: God, that was so helpful. Can we walk through each of them, and can y’all talk to me about the antidote for the people listening?

Julie Gottman: Sure.

BB: So criticism, verbally attacking personality or character—and I’ll link to this information, so I know a lot of people listen when they’re running and are out walking or jogging or driving. I’ll get you all the information to everything the Gottmans offer on the show page, all the links, their new course that you can take. Everything will be there, so don’t worry about taking notes. So criticism, the antidote is the gentle startup, and, John, you walked us through that, and you did too, Julie, talking about feelings using the “I statement” and expressing a positive need.

John Gottman: Right.

Julie Gottman: That’s right.

BB: Can I give an example?

Julie Gottman: Mm-hmm.

BB: Oh my God, I’m putting myself in the Gottman Love Lab. It’s not good. So Steve’s a pediatrician, and so that’s been doubly hard for us, because I think he should have all epidemiological answers and cures to what’s happening with the pandemic. So instead of being critical where I’m like, “Well, what do you mean you think it’s OK for Charlie to go do this? You didn’t last week, and you’re just wishy-washy, and you’re not taking a stand,” and that’s me being critical because I’m the cat. And so instead I use an “I statement” and express a positive need: “I feel scared and anxious. It would be helpful for me if you walked me through your thinking on this shift in your decision.”

Julie Gottman: Woo! Congratulations. Excellent job.

BB: I’m exhausted, man. Where do I get to discharge my anger and fear?

Julie Gottman: You can say, “I’m furious.”

BB: Now where do I get to discharge it?

Julie Gottman: I don’t know. Beat up a pillow. Play tennis.

BB: I do play tennis.

Julie Gottman: Yeah, there you go, see. Go for a run. Take a hot bath. Take a cold shower. Write it. Write it. Journal it. Write it down. Get it down on paper.

BB: Just don’t work it out on our partners?

Julie Gottman: Probably not.

John Gottman: The anger is OK. So when we code for anger in the lab, it doesn’t predict anything bad. In fact, if women suppress their anger, it predicts the relationship will deteriorate over time. If women become compliant and don’t really ask for what they need, the relationship is hurt over time. So anger doesn’t hurt a relationship, but it’s the contempt and the criticism that hurts the relationship. So you can say, “I’m angry,” and be angry when you’re saying it. You can say, “I’m furious. I can’t believe you changed your point of view. I was counting on you being a rock, steady. And now you changed your opinion? I’m furious that you did that. Help me understand how you changed your thinking.” So that’s anger, but it’s also gentleness.

BB: But that’s so beautiful. That didn’t hurt my feelings when you did that to me, John. That let me know how you felt.

John Gottman: Yeah.

BB: And then you were actually curious about something that I’m thinking.

John Gottman: Well, that was—I was just paraphrasing what you said to Steve.

BB: But it sounded better when you said it, I think. OK, so contempt to me feels dangerous.

John Gottman: “You idiot! How could you think one way one time, and—you call yourself a physician? You’re not a physician. You’re just a wishy-washy idiot.”

BB: Is name-calling usually filed under “contempt”?

Julie Gottman: Yeah. And sarcasm, mockery. I know, we can’t use sarcasm, gosh dang it. So putting your partner down with a sneer—it’s got a sneer in it, right? It’s got the eye roll.

BB: OK.

Julie Gottman: If you have teenagers, you know contempt.

John Gottman: Scoffing.

BB: Scoffing.

Julie Gottman: “You’re disgusting. What’s the problem with you?”

John Gottman: “That’s what you think?” [Laughter]

Julie Gottman: “Oh yeah? Well, I’ll tell you something. you have no brain cells left.”

BB: Oh God, OK, I get it. OK, this is—it’s shame.

Julie Gottman: That’s right.

BB: It’s belittling. It’s—OK. The antidote is to—this is my favorite antidote. I know you’re not supposed to have a favorite, but “Build a culture of appreciation, remind yourself of your partner’s positive qualities, and find gratitude for positive actions.” How does that work?

Julie Gottman: I know that neither one of us has very many brain cells left, but your brain cells excel them all.

John Gottman: Oh, thank you.

BB: You’re magnificent.

John Gottman: Thank you. And it even works better to pick specific things.

Julie Gottman: Like his brain cells.

John Gottman: Like, “I really like the color you’re wearing. It makes your eyes come out. You look beautiful today.”

Julie Gottman: Oh. Thank you, darling.

John Gottman: “I appreciate your looking great.”

Julie Gottman: Thank you, sweetie. I love you, too.

BB: I’m just telling you, they’re fixing to make out again if y’all aren’t watching. I can just feel like—OK, OK, so build a culture of appreciation is just a—not in the middle of a fight, but a daily gratitude, daily like, “I see you doing this for me,” or “I see you taking care of this for our family.” OK, so I get that. And is that protective, that culture of appreciation in a couple and a family?

John Gottman: Exactly, yeah. It’s like you’re building an emotional bank account between you. You’re putting deposits in that bank account, and the deposits can be really small. They can be just being interested in what your partner’s saying and acting interested. Again, all of this stuff only works within the context of a relationship where people are taking care of each other. They’re really nurturing the relationship. They’re nurturing their friendship. They’re having fun together. They’re playing together. They’re learning together. They’re enjoying lovemaking together. They’re cuddling. They’re holding hands. They’re doing all that other stuff instead of really the relationship becoming a desert, because they’re focused on either the children or work. And that’s the mistake that the devitalized couples are making who don’t have the Four Horsemen. They’re ignoring the relationship entirely.

Julie Gottman: Let’s not forget that what we saw with the master couples is that during conflict they would have five positive interactions for every one negative interaction. So where is that five coming from? Well, it’s coming from expressing appreciation, expressing admiration—turning towards each other’s bids for connection is one of the most important pieces. Turning towards John calling me to ask me a question, and responding to him rather than saying, “Hey, stop interrupting me. I’m trying to read,” or just ignoring him completely, which is turning against or turning away. So turning towards each other’s bids for connection is one of the most powerful ways, even though it’s a small little nut and bolt, to really create friendship and trust, which, again, is the foundation of a good relationship.

BB: Were there any master couples that were not friends at all? Or is friendship a prerequisite—

John Gottman: No. Yeah, that just wasn’t the case. The master couples really worked on the relationship, and so even during conflict—for example, if I was listening to Julie and I really strongly disagreed with what she was saying when she was expressing her opinion, and I strongly disagreed with it, when I was listening to her, if I was a master couple, I’d be nodding my head. I’d be vocalizing, “Oh, OK, I see.” And I’d be asking questions: “So, how do you make sense of this, given your position?” So I’m really attending to her, even if I disagree with her. And I’m communicating that kind of validation. And she’s doing it for me when I present my point of view. So they’re working on the friendship even during conflict. So I think it’s the case that there are no master couples that didn’t work on their friendship, didn’t have a close friendship.

BB: Beautiful. All right, the next one. Defensiveness: Victimizing yourself to ward off a perceived attack and reverse the blame. And the antidote here is take responsibility, accept your partner’s perspective, and offer an apology for any wrongdoing.

John Gottman: Yeah, my hero is this lawyer on one of our videotapes, and he is so nondefensive. He’s my model. He’s helping his wife identify what about his personality makes her the most angry. He’s helping her be critical of him, and he says, “Well, is it the way I talk?” and she said, “Yes, it’s the way you talk it.” “Well, what about the way I talk? Is it—do I sound kind of authoritarian?” And she said, “Yes, you do. It’s like ‘I have spoken.’ That’s the way you sound.” He said, “Well, it seems to work in the courtroom.” She said, “Well, it doesn’t work with me.” He says, “Oh, I can see that. So sometimes when I talk I use a tone of voice that is really definite and authoritarian and that makes you angry, is that right?” “Yes,” she says. I love this guy.

BB: Wow.

John Gottman: So that’s taking responsibility. He’s saying, “Yeah, you could be right. Maybe you’ve got a good point there. Interesting.”

BB: I love—and tell me if I’m wrong, but in all the books that I’ve read by y’all, which I think are all of them, I love the importance y’all place on curiosity. To stay curious with our partners. Is that true, or is that my reading into it?

John Gottman: Yes, absolutely. And that’s the Eight Dates book, was written to amplify that idea that we could create these eight dates and field-test them to keep curiosity alive in one another.

Julie Gottman: When couples become really, really busy—with kids, with school, with dealing with the pandemic, with the house, with work, with everything else—they forget that each person is evolving over time. They’re changing their values, their needs. Their bodies are changing. They’re having thoughts about themselves that are changing, and if we don’t ask each other those big open-ended questions from time to time, then we lose track of who the individual is. And big mistakes can be made because of that. For example, we can assume that our partner still really loves to go on 5-mile runs. Well, they haven’t gone for a while. Well, let’s say they haven’t gone for three years. “How about you going for a run with me now?” and she may say, “You know, honey, I had a knee replaced a few years ago. I don’t run anymore. Did you not notice?” So it’s really important to keep in touch with each other by asking each other questions and continually understanding who our partner is evolving to be.

BB: That also leads to the earthquake that has been 2020, because 2020 changed me. I think it changed our relationship, and it changed my husband. It turns out, I’m not as impervious to exhaustion and everything that I thought I was. It turns out, I’m not superhuman. It turns out that I have a breaking point where I should have been breaking a long time ago earlier, and that I was pushing through. And when you say, “People are busy with—” so many people—I’m in my mid-50s. So many people my age, it is our kids, it is school, it is our jobs, and it’s our parents. But I’ve changed. I’ve changed, and everything has changed. My body has changed. I’ve changed. My tolerance for things have changed. My wants and needs for my career have changed. And so this idea of curiosity being foundational to the friendship that is part of being a master couple is so—because I think it’s easy, don’t you think, to not be curious and look up one day and say, “I have no idea who I am, and I sure as hell don’t know who you are”?

Julie Gottman: [Chuckle] Yeah, I think that’s absolutely spot-on. I’m turning 70 this year, and one of the things that I’m known for is being idiotic when it comes to energy. So I’ll put out huge amounts of energy, tons and tons and tons of energy, thinking that I’m still 40. And then what happens for me—this is how I find out that, by golly, I am exhausted—is that I’m out doing whatever exercise—speed walking or hiking or something—and the Earth’s gravitational pull suddenly becomes very, very strong and I fall down. OK, so I fall down and it’s not that easy to get up. Then I go back to what I was doing, and I’ll keep doing it, and then I’ll fall down again. Well, a very good signal that I’m overwhelmed is that I think in the last four months I’ve fallen four times, and that was after having shoulder surgery. So we have this feedback to ourselves that we really need to listen to, we have to pay attention to, and then we have to share with our partners what’s going on for us. So I have a very, very hard time telling John about any physical weakness or any physical pain or anything like that. I was raised as a total stoic. We never, ever, ever were allowed to complain about anything. You’d get blamed for it if you did. So I’ve finally gotten to the point where within 24 hours I can tell him that I fell down.

Julie Gottman: [Chuckle] That’s getting better than maybe a week or two, and God bless him, I mean what I’ve learned about John, which I didn’t know, was that he is the most incredible, loving, caretaking nurse you could ever desire. He is so sweet and caring. He’s a fabulous chef. He makes great tea, great meals—

John Gottman: Chicken soup.

Julie Gottman: Great chicken soup, which, I swear to God, has healed me.

John Gottman: Thank you.

Julie Gottman: He is so loving. It’s the complete opposite of what I grew up with, and it’s been very, very healing. But if we don’t, as you point out, make ourselves vulnerable, talk about ourselves as well as checking in with our partners and asking them how they’re really feeling, how they’re really doing, day by day through this pandemic—because it changes every day—then we lose touch with one another. And we really don’t want to do that.

BB: Hard. And beautiful. And—yeah, I was raised—you didn’t see me, but I was there with your family. Fifth-generation Texan, we don’t miss work, we don’t get sick, we don’t get hurt, and if you do, “What stupid thing did you do to land yourself there?” and keep it quiet, and so—and then I’ve got the same kind of loving, caregiving husband. The vulnerability, the curiosity, I’m learning. OK, last one, stonewalling. Man. Withdrawing to avoid conflict and convey disapproval, distance, or separation. The antidote here is physiological self-soothing, taking a break, and spending that time doing something soothing and distracting.

Julie Gottman: Right.

BB: That is hard, because let me tell you, when I get stonewalled, I am the person that’s like, “Get back in here and fight this out with me,” like—and even Steve might say, “Hey, I just need a 10-minute break. Let me just get my thoughts together.” And he’s intuitively good at that and I’m like—yeah, I think that’s hard. So what drives stonewalling, and what do we have to do?

Julie Gottman: Beautiful. So, what drives stonewalling is when you’re talking calmly to your partner and you’re feeling more attacked and more attacked, more criticized, more put down, and your heart rate is skyrocketing, you’re going into fight-or-flight while you’re sitting there. So John and I could be sitting here looking as calm as can be from the outside, but inside, my whole body is ringing alarms saying, “Get out of here, or fight, fight, fight.” It’s a saber-tooth tiger. You’ve got to fight for your life. And when that happens, the blood from our prefrontal cortex moves into the back, into the motor cortex, where it’s enervating our bodies to run, or to fight. Therefore, with less blood up here in the prefrontal cortex, we can’t listen accurately, we can’t interpret what our partner is saying, we can’t problem-solve, we can’t think creatively, and we certainly can’t speak gently. This is lacking enough oxygen and blood to function well.

BB: So what if you’re in that place, Julie, and you’re in the lizard brain, your prefrontal cortex is offline, and you just keep getting pushed and pushed and pushed?

Julie Gottman: OK. So here’s what you have to do. You have to call for a break.

BB: Got it.

Julie Gottman: Tell me one time that you’ve stayed in there and fought, fought, fought and it’s turned out well.

BB: Zero. Professionally or personally. Zero.

Julie Gottman: You bet. Me too, me too. So you call for a break, and there are some secrets to how you do that. One, you say when you’ll come back to continue the conversation. Therefore, your partner will not feel abandoned. So you can say, “I’ll be back in 10 minutes,” or, “I’ll be back in an hour.” Give yourself a minimum of 30 minutes to an hour to calm down, if you’re the one who’s flooded.

BB: So if you’re flooded, is half an hour kind of the neurobiological reset time minimum?

Julie Gottman: Minimum. Minimum for your body to begin to metabolize cortisol and adrenaline, those stress hormones that have flooded your blood system and your body when you’re in fight-or-flight. You’ve got to start metabolizing those out. But there’s a couple of other things. So you say when you’ll come back, you leave, and then don’t think about the fight. I’ve heard so many people say, “My adviser told me I should think about the best way to come back and say X, Y, and Z.” Well, that is exactly the wrong thing to do, because if you keep thinking about the fight and rehearsing what you’re going to say when you come back, or remembering what your partner said before you split, then you’re going to stay in fight-or-flight.

Julie Gottman: You’re going to be thinking about the fight, ruminating about the fight, and still not giving your body a chance to calm down. So instead, you have to take your mind off the fight completely and do something self-soothing, and that can be as simple as reading a book, watching TV, listening to some music, meditating, doing yoga, taking a walk outside, playing with the dog, or holding the cat. Anything that takes your mind off the fight. And then your body will slowly but surely calm down. You come back at the time that you designated earlier, and you’ll come back even if you’re not calm yet in order to ask for more time. So if you only gave yourself a half an hour, you’re not there yet after a half an hour, ask for more time. Come back, say, “You know what? I still need another half hour. Is that OK?” And hopefully your partner will say yes, and then you go take some more time to calm down. And what you’ll find when this prefrontal part of your brain is back online is that you’ve had a brain transplant and you’re a new person.

Julie Gottman: It makes a huge difference, and we saw that in the lab when couples would be asked to go into the waiting room and read magazines for 20 to 30 minutes, because we were having “technical problems” when one or both were flooded. They read magazines, didn’t talk to each other, and when they came back into the lab to continue the conversation, we couldn’t believe it was the same couple. So this really, really works, and it saves relationships from those horrible, regrettable fights you never want to have.

BB: Yeah, the words that leave a mark, the words that you can’t unhear.

Julie Gottman: That’s right.

BB: It’s interesting, because I keep going back, John, to the word that you used, “cherish.”

BB: I understand now, more than I’ve started this conversation—I’m so grateful that there really does have to be a foundation of positive regard and love, because I think sometimes when people ask for that time away—I think I made up a story about myself for many years that I’m really good flooded. I’m like an interrogator or Perry Mason trial lawyer when I’m flooded, and the truth is, I just get meaner. I don’t get any more productive. I just get meaner and more contemptuous, I guess. But I think there has to be a foundation, because if I’m arguing with someone and said, “You know what, I’m overwhelmed. I’m going to ask that we take a break, we come back in an hour,” that’s a vulnerable thing to ask, you know what I mean? It can’t be a tool without a foundation of mutual respect, because I think sometimes I hear people get put down for that, like “Why? What do you need? You going to go prepare arguments or what? Just answer me now.” As opposed to like, “I respect what’s happening in your body.” If the goal is not to win but to understand each other, why isn’t giving each other time for that helpful?

Julie Gottman: Right.

BB: Do you know what I’m saying?

Julie Gottman: Yes, but let me also say that we’ve seen a ton of couples who have horrible, horrible, horrible fights, horrible conflicts, and what is really, really helpful is at a time when you’re not in the middle of a fight, you sit your partner down and you say, “George, I want to tell you that I need something different when we get into horrible fights. You know those ones where I say something really mean and blurt out an angry word that calls you a name and hurts your feelings? I hate that I do that. I hate it. I don’t want to be that person. But I know that when we’re fighting and my voice gets louder and louder, and maybe yours does too, that I start to go into fight-or-flight, and I can’t think straight. I can’t listen. I can’t really feel what you’re saying. I can’t even understand what you’re saying. So what I would like to do is establish an agreement with you where if I get into that state, I want to be able to call a break, say when I’ll come back, and calm myself down, so that we prevent ourselves from having that terrible fight that ends up getting you hurt.”

BB: Beautiful.

Julie Gottman: So it’s a preface, you see. And you don’t even have to be great friends to do that. This creates the friendship, because what you’re doing is you’re protecting your partner from the meanest part of you, and you’re protecting the relationship from the fault lines that John was describing that crack the relationship in two.

BB: We do this at work. So we have everyone, no matter what your position is, has the authority and the responsibility to call a timeout when things get unproductive, and we’ve never once regretted the timeout. We have on many occasions regretted not calling a timeout.

Julie Gottman: [Chuckle] Amen.

BB: Yeah. All right, so are y’all ready for a rapid-fire?

Julie Gottman: Oh boy.

John Gottman: Sure.

BB: Who wants to go first in our rapid fire?

Julie Gottman: John does.

BB: OK, John does.

BB: She’s cherishing you and letting you go first. Look, y’all are really insanely great. OK, number one. Just the first thing that comes to your mind. Vulnerability is—

John Gottman: Being open.

BB: Julie.

Julie Gottman: Exposing yourself.

BB: Number two, John, you’re called to be brave, but your fear is real. You can feel it in your throat. What’s the very first thing you do?

John Gottman: Breathe.

BB: Julie, same question. You’ve got to do something really hard. You’re going to have to be brave. You can feel your fear—what’s the first thing you do?

Julie Gottman: Put my hand on my heart.

BB: Is there a reason why we do that? It seems reflexive. Is there a reason we do that?

Julie Gottman: This is where we feel comfort.

BB: Mm-hmm, yeah.

Julie Gottman: We comfort ourselves.

BB: Yes.

Julie Gottman: It’s where we’re most vulnerable in our body, is here. Our belly, right, this whole area, and if we put a hand there, it feels like protection, warmth, comfort.

BB: Yes. John, something people often get wrong about you.

John Gottman: They think I’m a great therapist.

Julie Gottman: Get out of here. Oh my gosh.

John Gottman: She’s a good therapist.

BB: Julie.

Julie Gottman: People think I’m very extroverted and I’m the opposite.

BB: Last show, John, that you binged and loved.

John Gottman: Away. I really loved Away.

BB: Oh, OK. Julie.

Julie Gottman: Rita. It’s Danish and it’s—

BB: I’ve seen it.

Julie Gottman: Fabulous. I love it.

BB: God, she’s so much trouble.

[Overlapping conversation</i]

Julie Gottman: Isn’t it great?

BB: Yes, but—

Julie Gottman: She’s my idol.

BB: She’s amazing. John, one of your all-time favorite movies.

John Gottman: Casablanca.

BB: Julie?

Julie Gottman: 2001: A Space Odyssey. I saw it 13 times.

BB: Are we talking about the same movie, like, “No, Dave, I can’t close the pod doors”?

Julie Gottman: Yes.

BB: OK. You’re a complex woman, Julie. OK, John, a concert you’ll never forget.

John Gottman: I guess it was a Bob Dylan concert in Boston when I was at MIT. And listened to those first songs in the 60s.

BB: I have goose bumps. What about you, Julie? A concert you’ll never forget.

Julie Gottman: Oh my God, there’s so many. Bruce Springsteen before he got famous, in Boston, 1973.

BB: The Boss before he was the Boss, I love it. OK, John, favorite meal.

John Gottman: Schnitzel. Wiener schnitzel and a great salad and spaetzle.

BB: Wow, yum. What’s on your salad? What kind of dressing.

John Gottman: Usually Caesar salad dressing.

BB: God, yum. I’m starving. That sounds so good. I love schnitzel, in general. OK, Julie, favorite meal.

Julie Gottman: God, that’s hard. Probably lasagna and a huge hot fudge sundae with chocolate ice cream, which I haven’t had in about a year and a half. I really miss it.

BB: Ooh, I’m going to the Gottmans’ for dinner if anything’s like that on the—OK, John, what’s on your nightstand?

John Gottman: A lot of books. And a recent Jack Reacher novel by Lee Child, and also a book called Bifurcations in the Plane, translated from the Russian by Andrew Path. So it’s about differential equations.

BB: Sounds like a page turner.

John Gottman: Yeah, it really is exciting. It’s a math book. I love reading mathematics.

BB: Wow, Julie, is that book on your nightstand, or what’s on your nightstand?

Julie Gottman: No, Brené, it is not. It is not. OK, so Unorthodox, the book; Radical Judaism; a book by Abbie Hoffman, whose name escapes me at the moment.

Julie Gottman: Mary Oliver’s poems.

Julie Gottman: Oh, Mary Oliver’s poems. I have three books of Mary Oliver’s poems.

BB: There’s not enough books on Mary Oliver’s poems. OK, John, a snapshot of an ordinary moment in your life that brings you joy.

John Gottman: This is a picture I took of Julie holding our daughter when she was about 3 months old, and she’s looking in the mirror and I’m standing behind her, and I took—I’m not a very good photographer, but this picture captured the love that Julie had for our daughter, Moriah. It’s my favorite snapshot.

BB: God. Beautiful. Thank you for sharing that with us. Julie?

Julie Gottman: Standing at the top of Turtleback Mountain, which is a mountain not far from here. It’s cold. It’s windy. The sun is shining. The sea is sparkling. The grass is dancing. The trees are dancing. Leonardo Moishe Gottman, the dog, our Welsh corgi, is sitting at my feet.

John Gottman: You’re happy.

Julie Gottman: And the view is magnificent.

BB: Mmm, I can smell it. I can smell that, where we are. OK, John, what are you deeply grateful for right now?

John Gottman: I’m deeply grateful for the love I have with my wife and with my daughter.

BB: Julie?

Julie Gottman: I am really grateful that we’re having this interview with you, actually. Because you are so real. You walk the talk. You’re vulnerable. You are talking about yourself. You are sharing corners of your life with us, and I feel so honored and privileged to be here with you, so I’m very grateful for that. And that John and I can do that together on one computer, rather than two, which I couldn’t handle technologically.

BB: We did it. I feel like the word “gratitude” doesn’t even cover how I feel. Just on behalf of all the people whose lives that you’ve made better by inviting us to reflect on ourselves and how we love each other. You know that saying, “We stand on the shoulders of giants,” and I just think you’ve got millions of us who just are better people because of y’all, so I am deeply grateful. I’m so grateful I’m going to challenge you with a very hard task. Are you ready?

Julie Gottman: OK.

BB: Y’all both gave us a mini-mixtape, a playlist. I’m going to read the songs to you, and then your chore is in one sentence to tell me what this playlist says about you. Julie: “John O’ Dreams,” Cherish the Ladies; “Imagine,” John Lennon; “Woodstock” by Joni Mitchell; “Fairytales” by Sara Bareilles; and “Take Me to the River” by the Talking Heads. In one sentence, what does this mini-mixtape say about Julie Gottman?

Julie Gottman: I’m a feminist who loves singing to my daughter, being a mother, and like John Lennon, except less poetically, imagining, especially after the last four years that this world can be better and will be.

BB: Incredible. That was—you just crushed that. You ready, John?

John Gottman: Sure.

BB: “The End” by the Beatles; “Something in the Way She Moves,” the Beatles; “The First Time Ever I Saw Your Face”—is it Ewan MacColl?

John Gottman: Yeah.

BB: Is that how you pronounce it? OK.

John Gottman: Ewan MacColl.

BB: “Ain’t No Sunshine When She’s Gone,” Bill Withers; “I Know You By Heart,” Eva Cassidy; and “Both Sides Now” by Joni Mitchell. What does this playlist say about John Gottman?

John Gottman: Well, I’m a feminist. I really love women. I really love love, and want to nurture it everywhere I see it, and I really love peace and justice in the world. I’m a conscientious objector against war, and I love the equation in the Beatles song: “In the end, the love you take is equal to love you make.” So I’m a mathematician, too, and I love to see an equation like that.

BB: That is maybe my favorite equation in the world.

Julie Gottman: It’s the only one I remember.

BB: Yes, it’s really. Yes, and it’s the only one in the end that matters maybe.

John Gottman: Yeah.

Julie Gottman: Yeah.

BB: John and Julie Gottman, thank y’all so much for your time. Thank you for the love. In the end, the love you take is equal to the love—you’re going to be taking a lot of love, you two.

John Gottman: Thank you, Brené. It was a pleasure to meet you.

BB: Yeah.

Julie Gottman: Thank you so much. It was so fun. Just loved meeting you.

BB: So fun. Thank y’all.

[Music]

BB: I have formally committed to memory these Four Horsemen: criticism, contempt, defensiveness, and stonewalling. Oh no, no, these are the fault lines that crack the foundations of relationships. And you know what I love, as a researcher, specifically? I love that creating change is not about quick tips and tricks. It’s about commitment to maintaining curiosity and building a foundational friendship and appreciation and respect for each other. The Gottman Relationship Coach is an online program that I talked about in the intro, where they’ve taken these skills and you pace yourself through it. Their website is gottman.com, and that’s for the Gottman Institute. Social links, you can follow them at @GottmanInstitute on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter, and we’ll put all of the links on the episode page to their work and resources. They just have a ton, including a handout that has these Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, along with how to repair from these behaviors. Church bulletin: Every episode of the Unlocking Us podcast has an episode page on BreneBrown.com. Easy to find, all the links and referrals that you need. Anything that we mention in the podcast you’ll find on the episode page on my website.

BB: A reminder, which I guess you’ll know because you’re here, that Unlocking Us is only available on Spotify. It’s free. You can listen at Spotify.com. There’s a whole new hub. You can find us, mini-mixtapes, all kinds of fun stuff. This week on the Dare to Lead podcast, a beautiful, soulful, important conversation with Chad Sanders, a writer, director, actor, musician, on his new book, which is entitled Black Magic: What Black Leaders Learn From Trauma and Triumph. It’s such a moving, affecting conversation. All right, y’all, thank you for being here. Thanks for sharing this experience with me. Thanks for being part of the community. Let’s stay awkward, brave, and kind and love each other.

Unlocking Us is a Spotify original from Parcast. It’s hosted by me, Brené Brown, produced by Max Cutler, Kristen Acevedo, Carleigh Madden, by Weird Lucy Productions and by Cadence 13. Sound design is by Kristen Acevedo, music by Carrie Rodriguez and Gina Chavez.

© 2021 Brené Brown Education and Research Group, LLC. All rights reserved.