Brené Brown: Hi everyone. I’m Brené Brown and OMG, holy crap, this is Unlocking Us. And let me just tell you right off the bat, I’m talking to Bono. I don’t know what happened at the Paramount Theater on that weird Thursday night, but we got mentally in sync, spiritually locked in together, and had one of the most amazing conversations of my life. Now, granted, if you can picture me at 17 with my Walkman hitchhiking through Europe, do not recommend, for parents or 17-year-olds. And the only cassette I had was you U2’s War album. I have been a U2 fan since the very beginning, and this event was sheer magic. I’m so excited and grateful to be able to bring this two part-er to you. I’m glad you’re here.

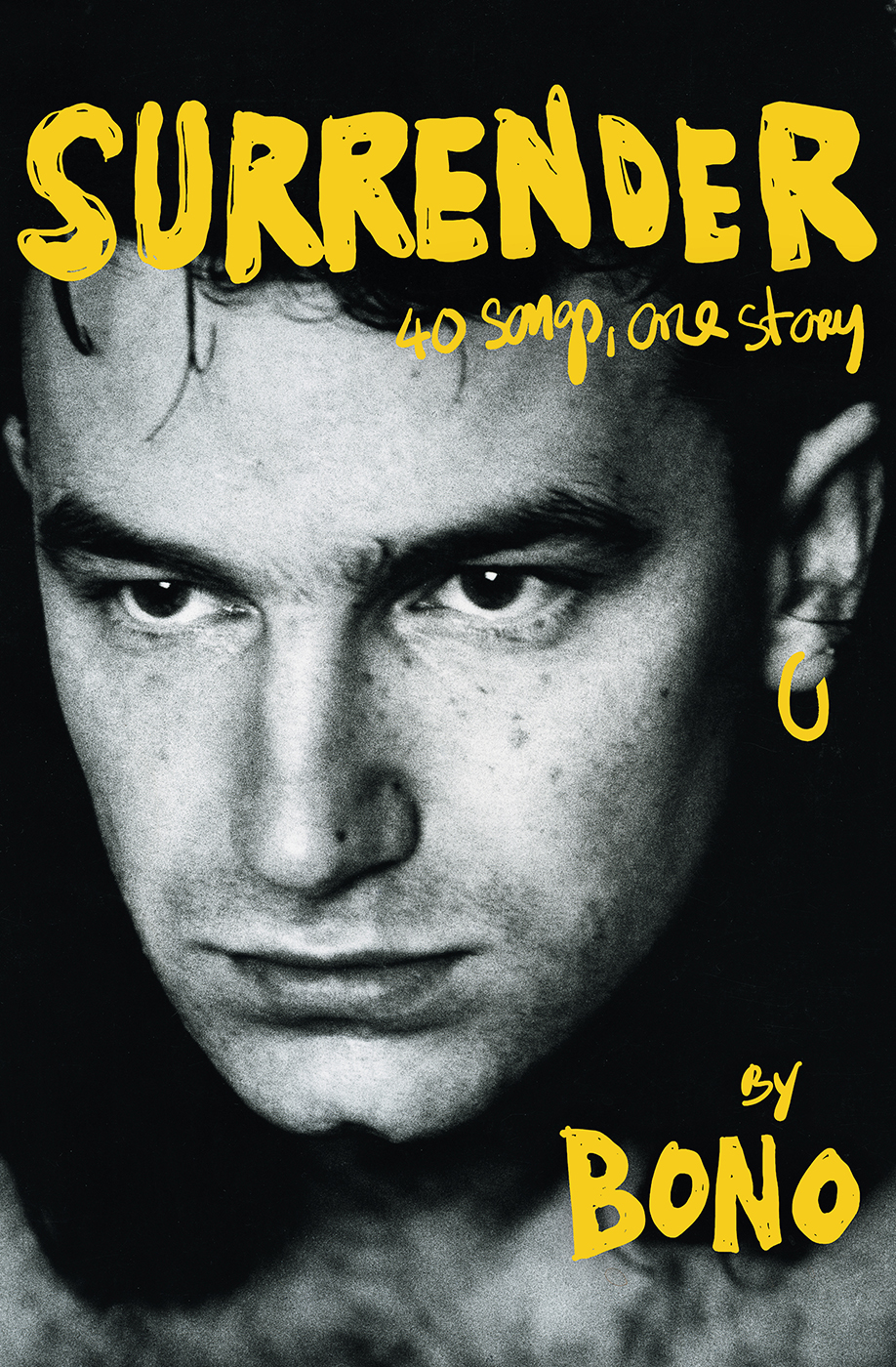

BB: Alright, before we get started, let me just say that this was a live event in front of 1200 of our closest friends at the Paramount Theater, the historic, beautiful, amazing Paramount Theater in downtown Austin. The event was presented by Austin City Limits Festival’s Bonus Tracks, ACL Fest Bonus Tracks for short, and we talked about Bono’s new memoir, Surrender: 40 Songs, One Story. Let me tell you a little bit about Bono. If you don’t know Bono, he’s the lead singer of the band, U2, he was born in Dublin. He met all the members of the band and Ali, his wife, the same week at school. U2’s sold over 170 million albums. They’ve won probably every award you can think of, including 22 Grammys. And this December, the band will receive the Kennedy Center Honors, which if you don’t know, I’m a Kennedy Center Honors junkie. Bono’s also a groundbreaking activist, he was a leader in Jubilee 2000’s, Drop the Debt campaign. He took the fight against HIV/AIDS and extreme poverty to just a new level. He co-founded sister organizations ONE and RED. He has received, again, a lot of awards for his music and activism and his new book, I just have to say, the memoir Surrender, it’s a love story. It’s a love story to Ali, his wife, to his family, to all of us who found all kinds of peace and challenges in the music and the lyrics. Let’s jump into the conversation.

Courtney Trucksess: (C3 Director, Sponsorship & Marketing) Welcome to the historic Paramount Theater.

CT: ACL FEST Bonus Tracks is proud to present a one-on-one conversation with researcher and author Brené Brown and U2 lead singer and activist Bono to discuss his new memoir, Surrender: 40 Songs, One Story. And now I’d like to welcome to the stage Bono and Brené Brown. Enjoy the show.

[applause]

BB: Woo.

BB: What’s up?

Bono: Glory, Glory hallelujah [singing in Elvis’s voice]. Sorry.

[laughter]

BB: Okay, I was ready to go.

B: Always for Elvis.

BB: Always.

B: Yes.

BB: Elvis, Johnny Cash.

B: Oh, Johnny Cash. Wow.

BB: You walk the line?

B: Yes, ma’am. I’m trying, I’m falling each time, but I’m there when I can.

[laughter]

B: I stood last night in front of the photograph of June Carter Cash.

BB: You were in Nashville?

B: I was in Nashville last night in…

BB: The Ryman.

B: In the Ryman, who’s the original Grand Ole Opry.

BB: Oh yeah.

B: So, they have these pictures, and I told everyone a story of meeting Johnny Cash over the while, over the years. And when he was rumored to be very sick… I mean really sick, I called to see if he was okay. And June, who’s in the photograph right there, was just, “Well, hi Bono. How are you? How’s Ali? How are the kids? How’s the Burlington Hotel?”

[laughter]

B: I thought it was just a wild thing. And I was like, “It’s great, the Burlington.” And she… “Oh, we miss that hotel.” And so we talked for about 15 minutes and I said, “Look, I don’t want to take your time, June, just checking in with Johnny, seeing if he’s okay.” And she said, “Oh, he’s right here, we’re in bed.”

[laughter]

B: She passed me the phone and Johnny says, “Sorry about that.”

[laughter]

BB: You’re at the Ryman at the high church.

B: Yeah baby.

BB: Welcome to Austin.

[applause]

B: Less of a church, more of a congregation. Steady on, Elvis.

BB: Steady on. It’s my 15 pages of notes.

B: Oh, I’m so sorry. It is a lot of book and…

BB: Oh god, it’s… Boy. I had such a hard emotional time reading this book.

B: Is that good or bad?

[laughter]

BB: So I’m not sure because I’ll tell you why. I was 17, I had just graduated from high school. My parents were in… My whole family was unraveling. I was supposed to come here to go to UT. I talked them into, instead of going to UT, hitchhiking through Europe for six months, and I had a Walkman and one cassette.

B: Oh, wow, wow.

BB: War. That’s it, that’s all I had, and it was the only cassette I had for six months.

B: Wow. Drowning woman.

BB: So, I’m going to start with this big question, a heavy question then I want to get into details. I’m a big music person, have been since I was young. Your music, War specifically, was the first time I had ever experienced music where there was enough room in the songs to hold me. There was room for my rage, there was room for my grief, there was room for my questions. They were big roomy, spacious songs that you could really move around in and ask a lot of questions. But the thing that pissed me off about that tape the most…

[laughter]

B: Knew there had to be.

BB: Yeah, no answers.

B: Right, Right.

BB: No answers.

B: Right.

BB: Big roomy songs that we could move around in, was that intentional?

B: You mean the lack of specific directions?

BB: The lack of no apology for uncertainty.

B: Oh yeah that’s really important. Yeah, we…

BB: Yeah, why?

[laughter]

BB: It was hard.

B: I mean, firstly, that album’s been on my mind recently. Ali, my missus, is here with me. And I had to explain to her on why our honeymoon album was going to be called War.

[laughter]

B: And it was an album we made out of a desire to find our way through the world, a way we were ready to give up. We weren’t sure that our music had any utility, that it could just be more of the same vainglorious kind of noise, which we also loved… Nothing like some vainglorious noise, but we were at whatever stage of development that we wanted more than that, we wanted something else from our music. And Edge started working on the arpeggiation and the song structure for “Sunday Bloody Sunday.” And it answered a sort of question that he was really, was more than nagging at him about, you know, can we write about real… The real world outside our windows in our own country and real people in real situations?

B: And that might answer the spiritual need to be useful in a world that was, you know, gone wrong in the old blues song sense. World gone wrong. And so we went for the, this kind of, it’s like the religious art meets the Clash and there were pencil sketches in one sense, but that’s why they worked, because they didn’t fill in too many details. And then you realize that that’s what’s really great about certain works. And even in, dare I say it, it sounds pompous as, I didn’t want to say it, like religious art, the great ones for me are more abstract. And I didn’t know then, because I was only a kid, it was on my honeymoon, I was 22, Ali was 21. And you know, it didn’t occur to me then that you could only approach certain subjects with metaphor and that, you know, the big subjects.

B: Especially you can’t approach the concept of God without metaphor, I means it’s ridiculous. So that’s where we, I suppose, left the space. We knew what we didn’t know, and that was, that’s why we left that be. And you are the only, the second person to say that to me in 40 years. And the other person who mentioned about the space was a person I only met recently too; a painter called Colin Davidson. Done amazing portraits of Seamus Heaney. Did one of the Queen actually, Queen Elizabeth. A brilliant portrait artist. And he was… Was just sitting there talking and he said, “I like your songs, the one where there’s room. Room for me to be in and room for all the different emotions and where you’re not being so specific.”

[applause]

B: There’s another way of looking at, which is just finish the fucking lyric.

[laughter]

B: So, who’s to say?

BB: Okay, I was really struck by something in the very beginning of the book. We’re going to go toe to toe on the title before this is over. So metaphysically, I know that the lyrics and the music come from the band’s heart, from the band’s head. But tell me about your lungs and tell me about… I can’t separate the spaciousness and the songs and your capacity for air.

[laughter]

B: Wow. That’s quite… Wow. This is going to be a very interesting occasion here in the great city of Austin.

[laughter]

B: I don’t feel dissimilar to the first time ever in Austin was in a club with the rather clever punk name of Club Foot and I don’t think there was AC we played in the summer, it was 100 degrees and I felt a little like this…

[laughter]

B: Trying to answer this, this question. You know, the man who opened my heart up at the start of the book, I eventually fess up to this open-heart surgery in the Christmas 2016, he was from Texas so his name is David Adams. I owe him my life. I know, you know, this fellow called Valentin Fuster was my cardiologist, a Spanish man, who said, “this is very, very important that you don’t die.”

[laughter]

B: “So listen to me,” and I did. And he introduced me to this fellow called David Adams, and he’s the one who said, “You’ve got lung capacity.” He said, “You’ve got about 130% lung capacity for a normal somebody at your age.” And I had thought that my gift, you know, that as a tenor was, I just didn’t know I was a baritone. But it turns out that I had some ability to just be able to sing at the top of my lungs. I was available early on in my life for, you know, shouting… shouting and roaring at my father and my brother as they shouted at me. But it’s much better to be in a rock and roll band and shouting at God.

BB: When I read that, there was a word that they used to describe what they found in your lungs, I think they pulled Ali aside and said, “Jesus, his lung capacity, and we have to use special wire to sew him back together because this thing’s…

B: Yeah, went on for a while, the sewing up but you know, isn’t it incredible this combination of science and butchery.

[laughter]

B: That is required to break and enter someone’s heart? And yeah, I just… I’m in awe of these physicians, I’m in awe of nurses. I’m in awe, especially in the last couple of years, we just owe these people.

BB: Yes. Come on.

[applause]

B: And, but air, air, it turns out is essential and yeah.

BB: So I thought this was really interesting. Here’s what you say, page 348, and you’re talking about the best theatrical show people, “They don’t put on what we think of as a big show. They just let you into their mood, which for those who love them is the most generous thing they can do.”

B: It’s different for me as a performer, because with U2, we’re trying always to break down the fourth wall. I used to just jump in the crowd that was easy, you know, hello, I don’t care about this distance between you and I, and you know, that’s what all that, that stage diving was and climbing up on stuff. And then when we started playing bigger venues, we had to figure out how to do that. And we used video screens and we tried to be artful about our use of them. And we tried to use whatever technology was available to break down the distance between the stage and the crowd. I then realized that some people like that distance, some performers like it, they actually liked it. And you can mean it people say, “Oh, I love the clubs because there’s no hiding, you know, in a club, man.”

[laughter]

B: I’m like, I’ve been to see bands in clubs and you know, you could be pressing up against the knee of the singer.

BB: Oh yeah.

B: And be a hundred thousand miles away.

BB: Oh yeah.

B: That it’s not about physical proximity, it’s about emotional proximity. So therefore, when people point to somebody like Miles Davis and say “He’d turn his back on the audience”… It was this, Miles Davis is one of the five great jazz geniuses really. And jazz is not my thing. I just want you to know, but Miles is my thing. And he would turn his back and he just couldn’t look at people when he wasn’t in the mood. And there are other performers like that. Van Morrison, can people say, “Oh, he’s very moody” and I say “Moody, whatever mood he’s in, he’s Van Morrison, you’re lucky to be in the room.”

BB: Yeah.

[laughter]

B: And let him be, just be yourself. U2’s different, our roots to revelation, to revealing ourself are through the songs and this performance, getting to a place with our audience where the U2 audience is part of it, and we get each other there. So, I have to be honest in the songs and the text may change only a tiny bit, but I can tell a very different story with the same text, with the same lyrics. In the book, I talk about Sinatra, and I had a recording of Frank Sinatra singing “My Way.” And in the 50s it’s a boast. It’s the one you all know, I did it my way. And then he records it 20 odd years later, and I have a copy of it, and it’s an apology, same, same arrangement, same key, same lyrics. And we start to realize the gifts of interpretive singing. If you’re true in to where you are at, there are ways of communicating honestly with an audience. Even if it’s the same script, ask any actor, you know, playing a great play changes every night. But I think letting people in on where you’re at is important in the communication.

BB: Let me ask a question. Is there a price, spiritually, emotionally, or physically for letting people into your mood?

B: Yes, but I hate whining rock stars. So, I have to be careful. Don’t you hate that? It’s like, “Oh, how did I get here? I so didn’t want to be on the radio this morning.” You didn’t have to be on the radio this morning. “Oh, how did I get here? The spotlight. Oh.” Like, fuck off. But look, my mate Gavin Friday always said, insecurity is your best security as a performer. And if we are… We are people, we’re unusual people who need 20,000 people screaming, “I love you” a night to feel normal. That’s accepted. But I think the performers I’m interested anyway are ones that need the audience. And you can tell there’s ones that I know I need that audience. And it makes me obsessional, people going to the bathroom during that song. How could they? Edge you will say, “Actually, there’s 70,000 people here. There’s somebody going to the bathroom at all times, Bono.” But there’s a lot of static out there as well as beer. And I think if you’re any good, you pick that up. And it’s a funny one.

B: And you expect the, the ego to be exploded and blown up, enlarged by this. But there is, if you’re asking, there is another side to it, which is the… That’s kind of imploding. And when I used to come back from tour and I’d come in to see Ali, and there was some… It was difficult to find equilibrium. And I think it was Ali who told me, “You know, by the way, in the film business,” she said, “A DP or an actor, they’ll meet on uncommon ground.” They meet their partners before they come home to get all that stuff out, whatever that thing is.

BB: The resync, the transition.

B: The resync. In recent times, that has not been a problem for me coming off the road. But the bumping on stage, I bumped into some awful versions of myself on stage. And I think it’s okay to say, but we got a boxing bag under the stage. So, I could leave the stage and just go at it. And, you know, it’s like, “What is that?” I would ask myself, “What is it? Who am I fighting with?” And I haven’t fully answered the question.

B: I just spent 560 pages trying to, you know… I failed. But I did know I had to surrender. But who I was fighting, that’s complicated. And I think it probably ultimately comes down to myself, and the different versions of yourself that you might meet out on a stage or in a song. I remember on the War Tour; we had a song from our first album called “The Electric Company.” And I remember just feeling just so just full of self-loathing and awfulness. And something was going wrong. I was fighting with whatever I was fighting with. And I kind of just… I put my head up against the drum kit, like giving it loads. And I’m just getting unwillingly, I suppose, wishing to feel that and the pounding of the drums. And I remember I started singing a sound. I’m just making [hum] in the middle of it, Edge has turned around, he’s turning up the feedback and it’s this wild sound going around. And I’m just singing [vocalization] and I noticed that my voice is forming into a melody. And I ended up singing in that moment. And I’m not exaggerating the despair I felt, real or imagined. I really did. It was a horrible feeling. And I was holding on for dear life. And I could hear this melody [vocalization], like this wailing Irish banshee. And then I realized it was “Amazing Grace.”

BB: Oh my god.

B: But here’s the thing. And this is maybe, obvious to everyone else who ever heard the song. But it wasn’t obvious to me. Amazing grace. How sweet the sound. And I went, “Oh, wow. Grace is a sound. It’s a sound.” And in that moment, I just held on to the sound and I found myself in that moment. I found whatever it was, and I just got back up and behaved myself like a proper pop star.

[laughter]

[applause]

BB: What does grace sound like?

B: Well, it’s some kind of surrender. And so, it depends on the beat. But in that moment, it was not a sweet melody.

BB: It was primal, huh?

B: It was primal. It wasn’t in my ear. There wasn’t “You’ll be all right, pet. You’re just on a rock and roll tour. You’ve been up all night. Give yourself a break.” It wasn’t that. It was some other wild primordial…

BB: Searing.

B: Yeah. It was just a really… I still have it. I still can walk out on stage and be terrified. And I’m not a person who you’d expect to have those kinds of anxieties. But they can get you. You might just be thinking people have gone through a lot of trouble to get tickets. What if you can’t make tonight the best night of everyone’s life? Well, hello. You know what I mean?

BB: Yeah.

B: But I mean, I will say this and it’s not just me. The band are like that every night. They want it to be. And they got that from punk rock. That’s a punk promise. Every night will be the best night we’ve ever had. But for a singer, it’s both exhilarating to reach for that, and terrifying to fear failing that.

BB: This is a perfect unplanned segue.

B: Mm-hmm.

BB: Exhilarating and terrifying. So, one of my fatal flaws when I’m reading something, especially there’s so much here, is my researcher turns on and I start looking for patterns and themes. And every time, I’d go 10 pages in this book and come back to this quote, I’d go another 10 pages and come back to this quote. Page 143. “I wanted to make music capable of carrying our own weight, even the weight of our own contradictions. To be in the world but not of it was the challenge in the scriptures, that would take a lifetime to figure out. As artists we were slowly uncovering paradox, and the idea that we are not compelled to resolve every contradictory impulse.”

B: Yeah, that’s right. That’s it. Yeah.

[applause]

B: It turns out I can live with or without you. And when I was writing that song, I was just completely torn because I couldn’t resolve a few things. Can I be an artist? Can I be a lover? Could we have a family? But I’m in a family that’s on the road. You know, all these kind of things. And there was so many sorts of things pulling at me and these polarities. And I realized it’s taken me a while to realize that that was actually what was… That was the terminals, I was holding on to them and they were just going through me. So, it’s going to sound really bad on the radio. I was reaching out there, like Elvis I’m trying to hold on to the positive and minus terminal and feeling the electric shocks. But it was a visual joke is my point. I realized that that was kind of powering, that the contradiction is exactly where to be. And I used to say Sam Shepard taught me that. And going into that section in the book, I said, “You know, Sam Shepard told me that.” And we went everywhere to try and find the Sam Shepard quote, about right at the center of a contradiction is the place you want to be. But we never found it. And I might have imagined it or just picked it up from his work. But it turns out that’s the thing I’m drawn to in everyone’s work, in your work. In painters I know. Colin Davidson I just mentioned. Duality.

BB: Duality.

B: And it’s Mona Lisa, is she happy or sad? It’s our music. U2’s music is full of joy. But there’s despair just right there. And we don’t have to resolve everything in these neat and tidy ways. And I might I say, your work is a real inspiration to a lot of us untidy people.

[applause]

BB: That’s the best compliment ever. I’m a big fan of untidy people. Let’s talk about that third way, that center space.

B: Right.

BB: So, Carl Jung said that paradox is the closest thing humans will ever get to to true spiritual understanding. And I think it’s the marrow of… When I read this book, I was like, “Shit. This is why those songs piss me off. But I love them.” It seems to me that you were born into the space that straddles tension. Bob, your dad, Catholic. Iris, your mom, Protestant. But that wasn’t the only interesting paradox. I love this line. “As a kid, I could see that the Hewsons tended to live in their heads, while the Rankins were at home in their bodies.”

B: Mm-hmm. That’s right.

BB: You came into this world in that third space.

B: Yeah, even my father, though, he himself embodied those contradictions and enjoyed them. So he’s working class from the Dub, as we say in Ireland, from Dublin. He’s Dub. He’s from the center of the city, a place called Cowtown. And he’s Catholic but working-class guy. But he’s listening to opera.

BB: Right.

B: He’s playing cricket. He is… This is like, “What?”

BB: And no strong accent either.

B: He had… Yeah. And then he starts dating my mother, who’s a Protestant. And in those days, that was not a good look for him. And at that point. If he’d been up north, it would have been the other way around. So, my father’s even view of nationalism was interesting. And he… Here’s another one, he used to say, you’d be very careful about nationalism. And Ireland’s about to burst into paramilitary flames at this point. And he would say things like, “What is Ireland? Ireland is the place that keeps my feet from getting wet. Yeah, that’s right. Synge said that.” Referring to the playwright, Synge. So, we went looking for that quote. That didn’t exist either. [laughter] And so either I made it up in my imagination or my dad made it up. I like to think it runs in the family. But you write what you need to hear.

BB: Yeah.

B: But, he enjoyed that contradiction. And then I’ve been telling people this over the release of the book. We used to sit in a pub in the local village where we live now, Finnegans in Dalkey. And we’d sit on a Sunday. My father would come and sit and I’d sort of… We kind of look at each other and sort of not talk about what was going on. And he would order, the Catholic, he’d order Bushmills, which is a Protestant whiskey from County Antrim, already. He’s just… He’s not going to be ever, don’t ever take me for granted for where I am or who I am. And I have that.

B: And he also had the presence. He had enough of that in him to make sure that we were protected going to church. He would drive us to the little Protestant church. And I mean, it was a small little church called St. Canice’s. And he’d drop us off there because my mother was Protestant. And so, she wanted to bring us up that way. That was going to be fine. And he would just drive, it was 100 yards up the road to go to St. Canice’s, the Catholic church. It’s so mad. But he had the character to say, I will do that. And he would honor our difference, I suppose, is what you’d call it. So I did learn that from him. I learned things I don’t want to do from him also. But I learned some good things.

BB: So, he… I really liked him.

B: He’s a lot of fun, isn’t he?

BB: Well, yeah, he really… He kind of dared you with his paradoxical ways.

B: Yeah.

BB: He kind of like said…

B: “You’re a baritone who thinks he’s a tenor.” That was his line. And it’s very accurate. And it’s a put down, but it’s very, very accurate. And so he had this kind of confrontational thing when Ali was pregnant with our first child, we came home and it was like this big emotional moment for us. She’s pregnant, we walked in and he just goes, “Ha, ha, revenge.” [laughter] But yeah, I obviously craved my father’s attention. He was lost to music, but he didn’t seem to notice it in me so much. And so, I just started, the more he ignored me, the louder and louder I became. And that’s where those lungs came from, Brené. It’s like… And, you know, I sang my way to right beside you here.

[applause]

BB: I have to say that I also really love this kind of defy description, push pull of Iris, your mom. She was like so practical and so frugal, master seamstress, but could get overwhelmed with and by laughter in a heartbeat.

B: Yeah, there’s a scene in the book where my father was a great DIY man, and he’s up making the shelves and wardrobes. And I’m in the kitchen with my mother and I just hear him, “Ahhhh!” And he runs out, “Iris, Iris!” He says, “Get… Call an ambulance! After castrating myself!” And he’s standing at the top of the stairs with an electric drill in his groin, like that. And my mother’s like, “Oh!” And I’m like, “Oh my god, this giant tree of 10 Cedar Road is about to be felled in front of my very eyes.” And I’m looking at him and she’s looking at him. She’s about to pick up the phone and she just starts laughing. And he’s like standing there like, “What?” And, he didn’t castrate himself, but I think part of her wished he did. [laughter] So she had that sort of very, laughing in church thing. And she, you know, what’s the story. I ended up in Mount Temple Comprehensive where I met Ali and the band. But before that, I went to St. Patrick’s Grammar School briefly. It didn’t work out well for either of us.

B: But in the interview with the headmaster, my mother was there, and St. Patrick’s Cathedral Grammar School had a very famous choir, a boys choir. And Mr. Horner, I remember his name was… The headmaster. And he said, “Now, Paul, have you any interest in singing? As you know, we’ve a world-famous choir here.” And I remember my throat going dry, and I remember this feeling inside me. Because if you’ve got the thing, whatever the thing is, you sort of know something’s in there. And I knew I had something, and I knew I wanted to sing, and I was trying to get it out. My mother goes, “No, he’s not interested in singing at all, Mr. Horner.” And that was the end of that.

B: And now it’s very easy to say that my mother was out of touch with her son. Not at all. I think she was in touch with me and she saw my discomfort, and she covered for me. But she was just a very practical person. So, my mother, I get, but my father’s little harder to explain. You would think that he would really encourage his kids to be involved in the music that he was so betrothed to, himself. That is a hard one to explain. In the book, I suggest that he sort of didn’t recommend people having dreams because to dream was to be disappointed. And I think this part of him was protecting me. Looking at my father now, I realize that I must not have been a comfortable presence.

[laughter]

B: Not just that I was really annoying and loud and a smart arse, but I was doing all the things that he wanted to. And that can happen with your kids. How are yours?

[laughter]

BB: My kids are good and I have to say sometimes every now and then when I feel like being small in my career, I remember a quote by again, Carl Jung, who said, “The greatest tragedy for every child is the unlived life of their parent.”

B: Oh.

BB: Yeah.

B: Oh.

BB: And so, then I think, “No, I’ve got to do my thing,” but…

B: I much preferred him to Freud.

[laughter]

BB: By a shit ton, as we would say here. Yeah.

[laughter]

B: You’ve met Richard Rohr, haven’t you?

BB: Yeah.

B: Franciscan friar. He’s the greatest gift to the world of theology and thinking. And I’m writing to him. I’ve started on my way here and going to be going past where he lives. I’ve had the pleasure of meeting him, but he quotes Carl Jung. Is it in Falling Upward?

BB: Falling Upward.

B: And he says that not only… This is an approximate, doesn’t sound very Carl Jung-ish, but not only are the things that brought you success in the first half of your life, no use to you in the second half of your life, they actually, they get in your way. Do you believe that?

BB: Hell yes.

[laughter]

B: All right.

BB: And do you want to hear something really weird?

B: Mm-hmm. If that wasn’t…

BB: No, I mean, no, I mean, y’all want to know something really weird? Page 10 of my notes, six quotes by Richard Rohr that I wanted to ask you about.

B: Wow.

BB: Yeah. Richard Rohr on St. Francis, Richard Rohr on death.

B: I went out to see him…

BB: This is crazy.

B: And he lives in the desert. He’s a Franciscan friar. He lives out in the desert in Albuquerque. And I was really taken by it. It’s called the Center for Action and Contemplation. And I really liked that order. Because it’s just so contrarian…

[laughter]

B: Because, normally you’re supposed to really contemplate before you act.

[laughter]

B: I mean, of course.

BB: Theoretically, yeah.

B: But I just liked that about him. And he’s the most… Yeah, he’s a very inspirational figure. I read him and I can’t claim to understand everything he’s written.

BB: Me neither.

B: But he is, he’s on a whole other level, really. And I don’t know if you agree with this and maybe this is off topic and please cut it out.

BB: No.

B: But as you know, I’ve been… I’ve never found a church I could really feel too comfortable in. And I think that’s okay for me. I’m part of a liquid church. I don’t mean the pub.

[laughter]

BB: I’m with you.

B: Jack, Father Jack used to say, “No, we’ve got this community on the road.” But I am finding myself more and more attracted to being in more formal sacred spaces. And even though I’m suspicious of kind of… I’m kind of finding myself going in the back of cathedrals and enjoying the symbolism. And they’re not any one denomination or anything. I’m sure I would feel equally at home in a synagogue or whatever. But I’m… Is there anyone else out there missing ritual ceremony, the routine, the dance, I suppose? And these metaphors, I love stuff like baptism. Like, wow, it’s such a powerful thing, you just… You’re under the water, you died. You come back up and I love weddings. I went to a… Irish weddings are mental, by the way. And…

[laughter]

B: There are more people having sex…

[laughter]

B: At the wedding than the couple. I mean, in the room.

[laughter]

B: It’s mad. And I mean, people it’s… People are very sexed up at weddings. And…

[laughter]

BB: Very moved by the tradition.

B: Very moved by tradition. Anyway, this was not happening at this wedding… Or maybe it was, but a friend of ours was getting married and they’re very kind of clever people and quite sophisticated in their approach to life. And I was taken aback. They had a very traditional wedding. And the bride kneels and the groom kneels and they took their vows. And I was like, “Wow, I didn’t expect it of these people.” They’re like, hipsters and kind of… And I said it to the mother of the bride, whom is a family friend. And she said, “This has been going around. It’s taken about 2000 years, but they’ve really got this one figured out.”

[laughter]

B: And don’t you think it’s like some of these ceremonies have an economy of design about them. That’s really attractive.

BB: A hundred percent.

B: And I’m… Again, I don’t come from that religious background. It’s a different thing from where I… But I just wondered if people are missing that in their life, that… Let’s call it a dance or something else or just a way to negotiate this. The madness of the moment we are all in. And I’m sure everyone agrees this is mad.

[applause]

B: I know everybody thinks their time that they’ve grown up in is compromise and things have never been this bad. The young people don’t know.

[laughter]

B: And then, no they do. Young people really do know. They know this is mad. People are not having kids, young couples because they think it’s mad.

BB: No. That’s right.

B: Where’s the future? Where are we going? And this negotiating modernity… I just wonder. I mean, some of the most inspirational people in my life are atheists and committed atheists. Brian Eno has called himself just in the last week to me. “I’m an evangelical atheist,” he said.

[laughter]

B: And he said, “But I’m dating a Christian to see what it’s like.”

[laughter]

B: He just said this this week. And so I… I’m in awe of the fearlessness and the courage for people to negotiate their lives with the idea that this is it. So, let’s not get this wrong. And I really respect that. But I think these empty churches, these empty chapels, these empty cathedrals, these empty town halls, school halls, I think there might be a use for them in the way that there hasn’t been for a long time, where people just love to sing together, to choral singing. Are you aware of the artist, Es Devlin? She works with U2 on our stuff. She’s an amazing artist in her own right. And she’s just done this thing in London, but she’s doing it in different cities. Should get her to Austin. She’s taking all the species that are endlings, that are dying and making these sculptures with them, sort of drawings of them. She did one as a mirror image of St. Paul’s Cathedral and then brought these choirs to sing because choral singing, we don’t hear it. In Europe we hear it at football matches, which I do love.

BB: Yeah, I know. I do, too.

B: You’re going to get your fucking heads kicked in.

[laughter]

BB: No, it’s very liturgical.

B: What’s that?

BB: The soccer games. It’s very liturgical. It’s very call and response. Very from my Catholic upbringing.

B: Right.

BB: Yeah. And you’re going to get your fucking head knocked in. But then there’s a response. It’s so nice.

[laughter]

B: Now, whilst I can avoid, you’re going to get your F’ing heads kicked in, especially if it’s my head that’s going to get kicked in. But anyway, I just love people singing in the terraces like Irish rugby games and Welsh rugby games.

BB: Oh god.

B: Oh my god. Anyway, all of this just to say that this place that I wasn’t comfortable in, I’m not completely comfortable in, but I’m much more attracted to whatever the parade and whatever the procession. I’m really attracted to this in a way that I wasn’t. And, yeah.

BB: I think that’s… For sure it’s true for me. But I think there is some second half of life there about… I was listening to 90,000 people sing… I’m a Liverpool fan, but…

B: Wow.

BB: Yeah, so I was listening to them singing.

B: You never walk again…

BB: Oh, no, that’s not how it goes.

B: No, no, no…

[laughter]

BB: But I was like… And my husband was like, “What are you doing?” I said, “I think I miss church.”

B: Right.

BB: And he’s like, at Anfield? And I said, just mostly the call and response, the liturgical, the rhythm, the in communion with. Not the power over and the church bullshit part, just the people part.

B: I just didn’t have you down… I didn’t have you down for singing in the terrace Brené. This is. This is great.

[music]

BB: All right. Just I hope you’ll love this conversation like I love this conversation. Part 2 next week, if you are looking for links to the book, you can find them on brenebrown.com where we keep all of the podcast notes. Just look under Unlocking Us. I really, really recommend the book. I mean, if you’re a U2 fan, you won’t be able to put it down. But even if you’re not, it’s just… It’s incredible. And the audio. I’ve read the book and listened to the audio. Both are incredible. I will see you next week with Part 2. Stay awkward, brave, and kind. Rock on.

[music]

BB: Unlocking Us is a Spotify original from Parcast. It’s hosted by me, Brené Brown. It’s produced by Max Cutler, Kristen Acevedo, Carleigh Madden, and Tristan McNeil. And by Weird Lucy Productions. Sound design by Tristan McNeil and Andy Waits, and music is by the amazing Carrie Rodriguez and the amazing Gina Chavez.

© 2022 Brené Brown Education and Research Group, LLC. All rights reserved.