Brené Brown: Hi everyone, I’m Brené Brown, and this is Dare to Lead. Today on the podcast, I get to talk to one of my favorite researchers and writers, Dan Pink. In this episode, we’re going to dig into one of my least favorite feelings or emotions, but… Let me see if this is true. Let me think about this for a second. Yeah, I actually think it’s true. One of my very best teachers, regret. In his new book, the Power of Regret: How Looking Backward Moves Us Forward, Dan shares findings from two large studies on regret, and the data are fascinating. Let me give you one sneak peek that I think is so interesting. We have more regrets about the things we did not do versus the things that we did do. Oh my God, I think that’s so powerful and so true. Failures of courage, failures of kindness, not taking risks. Both Dan and regret are great teachers, great storytellers, and you won’t regret listening. I had to do it, it’s so bad, but ba dum tum tsh, Barrett’s laughing in the background. It’s one of these topics that when I talk about why I think it’s important and how I believe that regret is a function of empathy, people get really crunchy, people are like, “I got no regrets, I live with no regrets.”

BB: And I don’t think that’s a good idea. I don’t think that’s about living a courageous life, I think that’s about living a life without reflection and without learning from stuff that makes you feel like shit sometimes, and so this is an incredible conversation. I’m glad you’re here, I’m not even going to do the regret joke again, even though it’s so easy and just so funny. No, Barrett’s shaking her head. “Not funny.” Glad you’re here.

[music]

BB: Before we jump in, let me tell you a little bit about Daniel H. Pink, he is the number one New York Times best-selling author of seven books, including his latest, the Power of Regret. His deeply researched work includes the New York Times Best Sellers, A Whole New Mind, Drive, To Sell is Human, and When. Oh God, When, was such a good book. Oh, they’re all great books, but When, on time, on the whole construct of time, it’s mind-blowing. His books have sold millions of copies, they’ve been translated into 42 languages and have won multiple awards. Over the last decade and a half, he also hosted a National Geographic television series, studied the comic industry in Japan, created a popular master class on sales and persuasion. Written the liner notes for a Grammy-nominated album and delivered more than 1200 lectures on six continents. He and his wife have three kids, two recent college graduates and a college freshman, and they live in Washington, D.C. Let’s jump in. Dan Pink, I’m so excited that you’re on Dare to Lead.

Dan Pink: Brené Brown, I’m so excited to be on Dare to Lead.

BB: I have to tell you… So, I have to start with this story. My very first book that was kind of out there was The Gifts of Imperfection, and they kept saying, “You have to have a big name blurb this,” and I’m like, “I don’t know anybody who’s going to blurb this book.” So, I got a couple of my friends to do it. And they were like, “That’s really nice. These are great blurbs, but we need high level blurb.” And I was like, “This is not going to work.” And they’re like, “Who would you think of when you think high level blurb.” I said, “Dan Pink?” They’re like, “Yeah, ask Dan Pink.” I’m like, “Okay, and if he can’t do it, I’ll get Gandhi to sign off or something,” and I was like, “There’s no way.” And somehow, I got your email address and I emailed you and you fricken said “Yes.”

DP: Well, I was glad to say yes, because I liked the book and your listeners who are only in the ears, who can’t see us, I’m in my office and I have that, I know exactly where that book is, that book is still on my shelf… My shelf back there. There was another thing that I have from you, Brené, where at one point, you sent me a t-shirt, it might have been a Daring Greatly t-shirt.

[chuckle]

BB: Probably did. Yeah.

DP: Did you have t-shirts for Daring Greatly?

BB: Well, we did. We did.

DP: I don’t think it was a Gift of Imperfection t-shirt, but it was a Daring Greatly…

BB: No.

DP: T-shirt. And I have a rather astonishing and embarrassing and to my wife mortifying collection of t-shirts, but that is one of my prized possessions.

BB: Oh my God, I’m so glad to be in your t-shirt collection. That’s good. Alright, I’m just going to tell you right off the bat that when I found out that you were writing about regret, I literally said out loud at my desk, “Hallelujah, Dan Pink is taking on regret.” And I’ll tell you why. I write about regret. I think the first time I wrote about it was in maybe Rising Strong, and there are only a couple of topics that I have written about where people are like, “Boo, go to hell, we hate you,” and regret is one of them.

DP: That’s why I wrote this book. I wanted to take that on because I’m convinced we’ve gotten regret completely wrong and that we can actually use it as a force for good, that knee-jerk reaction, you write about it in your latest book, that knee-jerk reaction to saying “No regrets, no regrets. Always look forward, never look backward,” is extremely wrong-headed and actually dangerous.

BB: Okay, before we get into this book, which I just can’t wait, and oh my God, Dan Pink, the researcher, the research you’ve done for this book is mind-boggling, let’s back it up a little bit and well, we always start here, tell us your story. Back it all the way up to being born.

DP: Being born, I was born on a July day. I was actually born in Wilmington, Delaware. My dad was working in Wilmington, Delaware, but when I was a little kid, we moved to Columbus, Ohio, that hotbed of social rest, and I grew up in Columbus, Ohio, in a very white, very middle class, very risk-averse, very conservative, very middle America, Fourth of July parade, football on Friday, night kind of town, and I had a perfectly pleasant childhood, what saved me though in my childhood and the great, great thing about growing up in Central Ohio is that the State of Ohio in general and Columbus, Ohio in particular, has outstanding public libraries, among the best public library systems in the United States, and so I spend a lot of time in the library, and had I not grown up in Columbus, Ohio, I don’t think I would have become a writer. I became a writer, I think, because I spent so much time in libraries as a kid, so I spent some time at libraries as a kid. I played a lot of sports as a kid. I was a fairly kind of nerdy, but okay, guy, I guess.

DP: I went to college, I liked college, I went to law school because I was a middle-class kid who needed something to fall back on, I decided I didn’t want to practice law because that was two soul hollowing, and I decided to work in politics, which proved somewhat soul hollowing. And then in this long and twisted tale, in my early 30s, I think I discovered what I had known all along, but was somewhat closeted was that in my heart, I was a writer and that’s what I should do.

BB: Okay. I’m going to back us up. What sports did you play in high school?

DP: Oh, I played every sport growing up. I played Little League Baseball, I played flag football, I played basketball. We had a very good basketball team in my high school, I didn’t make the basketball team, I didn’t make it in junior high either, but I played every form of recreational basketball there was. I played every form of recreational baseball there was. I played tennis. One of the things about growing up in Central Ohio is that everybody knows how to play sports, even the kids who are more like the more studious kids actually know how to play sports too, which was kind of a revelation to me when I came to the East Coast, because I came out of the Midwest where I was studious and maybe at the median of athletic ability, and then I had some encounters on the East Coast in other places like in Washington and whatnot, and I’m like, “Holy crap, I’m one of the best athletes here, this is amazing.” I’m median in Central Ohio, but you put me with a bunch of lawyers in Washington, D.C., and I can just dominate.

BB: Oh my God, that’s funny. Okay, first time you fell in love.

DP: Oh… I think… Okay, we’re going to go there. I am…

BB: This is not your average… This is not your average interview here Dan.

DP: No, no, no. It seems like it seems like you might prize vulnerability of all things.

[laughter]

DP: I think I was 17 years old.

BB: Okay. First regret you remember having.

DP: Can I go back to sports?

BB: Totally.

DP: I haven’t thought about this. Wow, that’s a good question. It involves sports because I’m in Ohio and clearly because of my birthday, I was not eligible for a certain year of Little League, you had to try out to do it, and there are like 11 kids trying out in one spot, and I didn’t get it, and I was really bummed out, and the coach at some point, maybe three weeks later said, “Well, we might have more openings, do you want another chance?” And I said “No,” because I was so pissed off and I regret, and I realized that was a mistake. About 10 minutes after saying that, I realized that I regretted saying that because I so so so wanted to play baseball.

BB: But you were pissed.

DP: Yeah, I was also 11.

BB: Yeah, yeah. Okay, college, what were you like?

DP: Well, I’m not sure I’m the best judge of that.

BB: Okay.

DP: We can bring in a panel of experts. I was pretty hard working, I actually really enjoyed college.

BB: Where did you got to school?

DP: I went to Northwestern University, I was a linguistics major, I had a great academic experience there, very rigorous academics there. I made some life-long friends. I had a very good time, I was kind of bummed out when college ended.

BB: Tell me about… I love linguistics. Tell me about the decision to be a linguistics major.

DP: Well, it was what I was interested in, so I ended up taking an introductory course in linguistics, and it was amazing. It was so interesting. I never thought about it before. I had always been a word person. I had always been a writer and a reader even as a little kid, and I enjoyed that sort of thing, but I had also had, I think, somewhat mathematical mind too, and so Linguistics is like this perfect juncture of those two ways of thinking…

DP: So, in my linguistics classes, I would have a class on metaphor with poets, people who are majoring in creative writing or English, but then I would have a class in something that was known as transformational grammar, and my classmates would be computer science students because transformational grammar is a set of rules that make up language and that… Blah, blah, blah. And so I really found it interesting. The other thing about it is that I was a slight, maybe a mild contrarian, and so everybody else was zigging towards certain majors, and I said I’m going to zag here. And the other thing about it, though, was that what I realized that the way I like to learn was sitting with a small group of people talking about stuff and then writing papers, not sitting in a 100-person lecture hall, receiving one way transmission and then taking a test, and so my courses for most of my… Certainly, the last two years of my college, and in some ways maybe the last three were very, very small, often five, six, seven people in the class, and so I actually learned a hell of a lot.

BB: So, one of the things that I admire about your work the most is your ability to craft a very tight story that is so subtly teaching the shit out of somebody. I don’t know how else to say it. I’m sure there’s a more eloquent way of saying it. Do you think that pedagogy in story telling that you do so well, and in some ways, incredibly uniquely, do you think that comes from linguistics? Do you think that is where that starts?

DP: Maybe. I don’t know if that’s where it starts. I think that the rigor of that way of thinking is very helpful, but I think a lot of it comes from being a reader and being disappointed when people don’t get to the point fast enough, or there’s too much fluff or it isn’t well supported. I’ve gotten in arguments Brené… As much as these kinds of arguments can be ferocious, I had an argument once about eight or nine years ago, with a buyer for a major book place, where I was trying to say to him, it was a him, that most non-fiction books are too long, that most non-fiction books would be twice as good if they were half as long. His view of that was like, “You’re a complete philistine. What are you talking about?” And I said, “Mm-mm-mm, I think there’s a lot of fluff there.” So, I tend to write books of the sort that I want to read, and I like things that get to the point, I like things that are… In the way that I write, I’m sort of an obsessive editor, and so essentially when I write, the way I edit is peculiar, but I almost always edit on paper, and so I cross out sentences all the time, I make every word fight for its life.

DP: Every word on that page has to talk to me and say, ‘I deserve to live on the page, Daniel, please do not kill me,’ and I say, ‘Well, why do you deserve to live on the page adjective?’ and the adjective has to tell me. What’s more is that when I edit, I’m sitting here in my office, there’s a chair right over there. And my wife, for every book that I’ve written, has read every single page to me in multiple forms out loud, and I have read to her every single page out loud because basically, I’m obsessive, that’s a short answer to my long-winded explanation, which is, I’m obsessive. I’m obsessive about the efficiency. This answer is completely betraying my philosophy, but people don’t have a lot of time and attention, and so you want to grab them, grip them, engage them emotionally and intellectually, because then what you’re saying just seeps into their marrow.

BB: God bless… You know, it’s so funny, the first time I read my books aloud is usually when I’m recording them, and I’m constantly stopping and telling whoever’s with me like “Shit, we should strike all that in a second,” but the reading out loud, that’s a really good thing.

DP: It’s helpful to me in reading out loud, and it’s also helpful for me to hear it out loud, and some of that might be in part of my misspent youth, I worked as a political speech writer, and so part of that is that kind of habit and training but for me, I process the words differently when I hear them and when I see them, not better or worse, just differently, and every once in a while I’ll hear something, it’s like, “Ooh no, no, no, no, no, no, no,” and we’ll make that kind of change.

BB: Yeah, I can tell you that your stuff is really… It’s not spare in any way, but it is impactful.

DP: Well, thanks.

BB: Yeah, we’re really going to get to know you in the most uncomfortable way before we go into this book, so Dan’s like “Shit, what did I sign up for?’”

DP: Yeah, I know, I know, I know. Ah, let me just… Pink checks his watch.

BB: No.

DP: Okay. Well, you already asked me a question about falling in love, which I don’t think…

BB: Yeah.

DP: Yeah, so… Well, this probably can’t be worse coming from you, but what have you got?

BB: Oh, it’s going to get worse. No. Okay, tell me about the political speech writing? Did you love that job? Was it like the West Wing? You had to have been good at it.

DP: Oh okay, alright, here we go. So, there’s three questions there… Alright.

BB: Yes.

DP: What was it like? Is it like the West Wing and did you love it? Okay, I’m going to answer the second one, it is not a thing like the West Wing.

BB: Damn it!

DP: That is so confected. First of all, people aren’t nearly that good-looking.

[laughter]

DP: People are much more bedraggled. I actually think in some weird way, the best representation in television of political life is Veep, even though it’s crazy, the amount of just insanity and clueless-ness that Veep shows is actually…

BB: Yeah.

DP: In some ways more accurate, so did I like it? See, I was into politics. I was really interested in politics. I thought it was a way to go out and do something valuable to the world…

BB: Yeah.

DP: And I found myself. I was one of three people in my law school class who graduated unemployed because I didn’t want to go work at a law firm or anything like that, and so I went out and found a job on a campaign afterwards, fortunately, my school had a loan payback program for people earning small amounts of money, which otherwise I wouldn’t… Honestly, I wouldn’t have been able to do that.

BB: Yeah.

DP: Here’s something I don’t… When I entered law school, I had been working at a job for a public interest group in Washington DC, making $13,000 a year. When I left law school, my first job out of law school on a campaign paid $12,000 a year, so all those student loans and years of education and the immediate payoff was negative, so… Well done Daniel.

BB: Jeez. Yeah.

DP: But I like politics, I like the excitement of it. It’s really interesting. You can really get to know people well. So I actually like being in the environment, we’re all working together toward a common cause, I like the project-basedness, especially of campaigns, because there’s a beginning, there’s a middle, there’s an end, there’s an outcome. You learn, you move on, and I like trying to do good things. I worked as a speech writer for the Secretary of Labor in the Clinton administration, Robert Reich.

BB: Oh my God, did you really… Yeah.

DP: When I was there, we worked our asses off and raised the minimum wage, and I’m like, “Whoa, wait a second, we worked a year, over a year pushing this and pushing this and pushing this,” and the minimum wage went up and people around America got more money that’s cool, you know, but at a certain point, it’s always working in the White House, and I liked it and I liked my boss, and I liked the people I was working with, but [a] it was all consuming, and [b] there was a part of it that felt a little hollowing, and I’ll tell you why, because I would be sitting at my computer… You know, it’s not like the West Wing. You know what it’s like, it’s more like people have this notion that speech writing is a bunch of people in smoking jackets sitting around thinking thoughts and whispering bon mots in the ears of the powerful. You know what it’s like? Honestly, it is like an urban war zone emergency room, and you are just stitching up bodies as quickly as you can, hoping they don’t die on your watch, that’s a closer analogy to it, because the pace is so so so ferocious.

DP: It’s exhilarating though. It’s really exciting. What happened though is that I realized that I didn’t want to spend the rest of my life in politics, because I looked down the road and saw people who were me, 10 years ago, 20 years ago, 25 years ago, and they were not happy, and I knew I would not be happy doing that. And the other thing is, is that at the time, from the time I was in high school really, I was always “writing on the side.” I did writing on the side, writing articles, essays, magazine articles, opinion pieces, blah blah blah, on the side for 15 years before I finally realized this, “hmm this thing you’re doing on the side, might be the thing you should be doing in the center,” and so…

DP: And I think there’s a lesson there Brené. I’ll extract a life lesson from anything, but I think there’s a lesson there, which is that we tell these young men and women to follow, “What’s your passion?” It’s a stupid freaking question, I hate it, and I think that’s a question we should be asking ourselves is, what do you do… What do you do when nobody’s watching? What do you do because it’s part of you, and I discovered over time that what I did was write, tried to figure stuff out and write about it and tell people about it, and I finally decided to take a flyer to do that, my wife kept her job, she kept her health insurance, and that was 20 years ago, 20 plus years ago.

BB: How many books ago was that?

DP: This is the seventh book in 20 years.

BB: Yeah. God. Okay.

DP: You know what it’s like to keep cranking them out, man, it’s hard.

BB: I do, I’m on seven… We’re together. Yeah. Alright, let’s jump in. The Power of Regret: How Looking Backward Moves Us Forward. Why regret? What led you here?

DP: I think it was because I had regrets of my own and that I was trying to figure out, and this is a book that I would not have written earlier in my life, I can’t imagine writing this book in my 30s, in my 50s, I felt somewhat inevitable, because I’m at a point in my life where I can look backward and there’s some mileage there, and I can look forward and let’s… I hope there’s a mileage there, and so I guess the catalyst was, we have kids who are roughly similar ages, the catalyst was that my elder daughter graduated from college, and I’m at her college graduation, and I’m in sort of disbelief, because I can’t believe this kid is old enough to graduate from college, because she was just born last week, and I can’t believe that I have a kid in college, because I graduated from college like four years ago, and I started thinking about some of my regrets about college, like what was my college… Oh man, I wish I had been kinder.

DP: Oh man, I wish I had taken more risks, oh man, I wish I had worked a little harder and what I found when I got back and very sheepishly talked to people about it, is that people leaned in rather than recoil, that people actually wanted to talk about it and wanted to engage and you know, as a writer, that’s an incredible reaction, so I actually was working on a totally different book and said, I can’t get this regret thing out of my head, and so I spent a month doing some research and I was already on the hook to write a completely different book, and I emailed my editor and said, I’ve got some good news and some bad news.

DP: The bad news is that the book you think I’m working on… I haven’t been working on… The good news is that I think I have something better. Please see attached my 25-page proposal for an entirely different book.

BB: They must get those a lot because I’ve sent many of those. How did it go over?

DP: Well, enough that I was able to put aside the other one and work on this one and devote two and a half years of my life to doing the research and the writing for this book about regret.

BB: Okay, so you’re thinking about your own life. My daughter’s in her first year of graduate school, it seems incomprehensible to me. Yeah, I have been reflecting a lot on regret. I am a huge fan of regret, as you know, which made me so excited about this book. Okay, so you… Using your word, sheepishly talked to a couple of people. It’s resonating. People are leaning into the conversation. What’s your next step? Where does the American Regret Project and the World Regret Survey come in?

DP: Okay, so I knew that this topic was out there that was really interesting, and I looked at some of the existing research on it, and I said, “Okay, this is really interesting research, but I think it’s not complete enough.” And one of the things, you know this very well, one of the things you see about the world of academics is that they’re very, very narrowly focused, and they don’t talk across disciplines.

BB: No.

DP: And I felt that there was this very constrained way of understanding this topic and so the other thing here is that I realized that the world we live in today is different from the world when I started writing books. I’m able to do massive, incredible research projects with only one or two people from the comfort of my garage here in Washington D.C., and it’s pretty amazing. So, I put together something, as you said, called the American Regret Project, which was a 4,489 person public opinion survey, a rigorous public opinion survey, representative sample of the American population, because I said, “We haven’t had a good survey on regret.” We had one, okay survey 10 years ago, but we haven’t had a good comprehensive survey of American attitudes on regret ever, I’m going to go do it on my own, working with a data analytics company and put it together and I want to see if there are differences based on race, age, gender, blah, blah, blah, blah.

DP: At the same time, I did something else that proved to be even more revelatory, which is that the World Regret Survey, where I just invited people around the world to submit their regrets, and we ended up with… It’s crazy because I’m insane, because I read them all. We ended up with 16,000 regrets from people in 105 countries, and that’s where I had a breakthrough with those 16,000 regrets from all over the world.

BB: What did you learn?

DP: Well, what I learned is that my quantitative survey wasn’t worth as much as I thought, because what happened was this, I wanted to know, what do people regret? That was one of the things that I was trying to figure out. Now, in your book, you mentioned this, you mentioned one of the studies that says, “Oh, 90% of regrets fall into these certain domains…” That’s totally right. Okay. And I was like, “That’s unsatisfying though.”

BB: It’s totally unsatisfying.

DP: They’re spread all over the place. What’s going on? So, I said, they’re not asking the question right. I’m a better researcher than Gallup, I’m going to go in there and I’m going to figure this out. And so, I go in there and I ask these questions about and have people list their regrets and put them in these categories: Is it a career regret? Is it a finance regret? Is it a health regret? Is it a romance regret? And I found that people regret a lot of stuff that it’s spread all over the place. Alright, then, and I’m preaching to the saved here… Because you understand that there is a conversation between hard research and storytelling, they talk to each other, that is the hard-headed academic research and the story telling are not separate domains, they are siblings, and they talk to each other and they enrich each other, you know that you’ve done that better than anybody, but for me, those 16,000 regrets were revelatory, and I’ll tell you why, I’ll give you one example. What I found is it over and over again around the world, people kept expressing the same four regrets, and these four regrets had nothing to do, little to do at least, with the domain of life, career, health, finances, whatever, they had to do with something deeper.

DP: And this is where my linguistics training paid off because Noam Chomsky taught us that languages have a surface structure and a deep structure, regret has a surface structure, career, education, and health. Regret has a deep structure; something else going on. So, let me give you, I think the best example of this, so I had… And this is so fascinating, and these regrets are just absolutely fascinating, each day the database would have a few more, and I’m like, “Holy moly. This is incredible.” So.

DP: If your listeners want a business idea, I’m here to serve… because I’ll tell you, for all you entrepreneurs out there listening to Brené’s show, here’s an idea for you, a travel agency that serves people who went, Americans especially, who went to college and didn’t study abroad, and now regret it.

BB: Wait. Just stop.

DP: You think I’m… Don’t laugh, man, I’m dead serious about this.

BB: No, I hear this, I hear this all the time.

DP: Yes, so that’s a regret. That’s an education regret in our surface structure. Okay, then I have huge numbers of regrets, the universality of is amazing, and you’re making me think about linguistics a lot, which I didn’t expect to do, but the universality of these regrets in the way that the sentences are constructed are incredible. I have literally hundreds of regrets that have essentially the same construction, which is this, X years ago, I met a man/woman whom I liked, I wanted to ask him or her out, but I didn’t because I was too chicken. And I’ve regretted it ever since. That’s a romance regret… Then I have other regrets, I have regret… Hundreds of them. I stayed in this lackluster job when I really wanted to start a business, but I didn’t have the guts to do it. So, that’s a career regret, so you’ve got these three regrets in totally different domains, but it’s the same regret, if only I had taken the chance.

BB: Taking the chance.

DP: And that to me was again, this conversation between the hard research and the story after story, after story after story, and when you hear that when your ear is attuned to it, as your ear is so brilliantly attuned to these stories, you say the people are trying to tell me something, and what they told me is over and over again, there are four regrets that they had, and the domain of life was less important than there’s a deep structure of human aspiration.

BB: I am geeking out so hard right now that I can barely focus on this conversation, I’m just telling you that I am nerding out y’all, it’s like Dan’s trying to sweet talk me. Okay, deep structure versus surface structure. This is the linguistics approach?

DP: Yeah.

BB: And we’re so embedded right now in a conversation, the subtext of this conversation that’s happening right now is this awful false debate around quantitative versus qualitative, that there should be no debate. We need both. If you told me you learned three wonderful things from two stories, it wouldn’t mean anything to me, and if you told me you learned from 100,000 things, but you don’t give me the deep structure, it means nothing to me. We need the lake that is both two miles wide and 20 miles deep, and that’s what you’ve done, so effin bravo.

DP: Well, thank you for that. And thank you for that analysis, even though I’m not a Baptist, but I wanted to scream Hallelujah on that one.

BB: Yeah, no… This is it…

DP: Should it be qualitative or quantitative? Yes.

BB: Yes.

DP: We have all these false dichotomies everywhere, but the answer to either/or is often, yes.

BB: Yeah, I had to do this tiny shout out before we get back to regret, for Karen Stout, who was a mentor to me, and she studied femicide, the killing of women by intimate partners, and I was the first qualitative dissertation in my Ph.D. program, and I had to fight for six months to even let it happen, and she ended up telling me around domestic violence, she said, “It would be so great if I could just go into funding agencies in the city and say, ‘Here are some incredible stories,’ but I can’t… And it’d be so great if I could go into the funding agencies, the same people and say, ‘Here are the statistics,’ but I can’t…” If you don’t have the data and you don’t have the story. You don’t have what it takes to move people.

DP: Amen. Sister.

BB: Yeah, so just incredible.

DP: Write it on a rock.

BB: Write it on a rock. Oh my God, tabletize it. Yes. Okay, tell me about how you… Because you’re who you are, I’m going to use this language, tell me how you language… What’s underneath the… What seems to belong in different domains… How do you language? I didn’t ask him out, I didn’t leave the job, I didn’t take the chance. How do you language that when you’re talking about regret, what is it that people deeply regret?

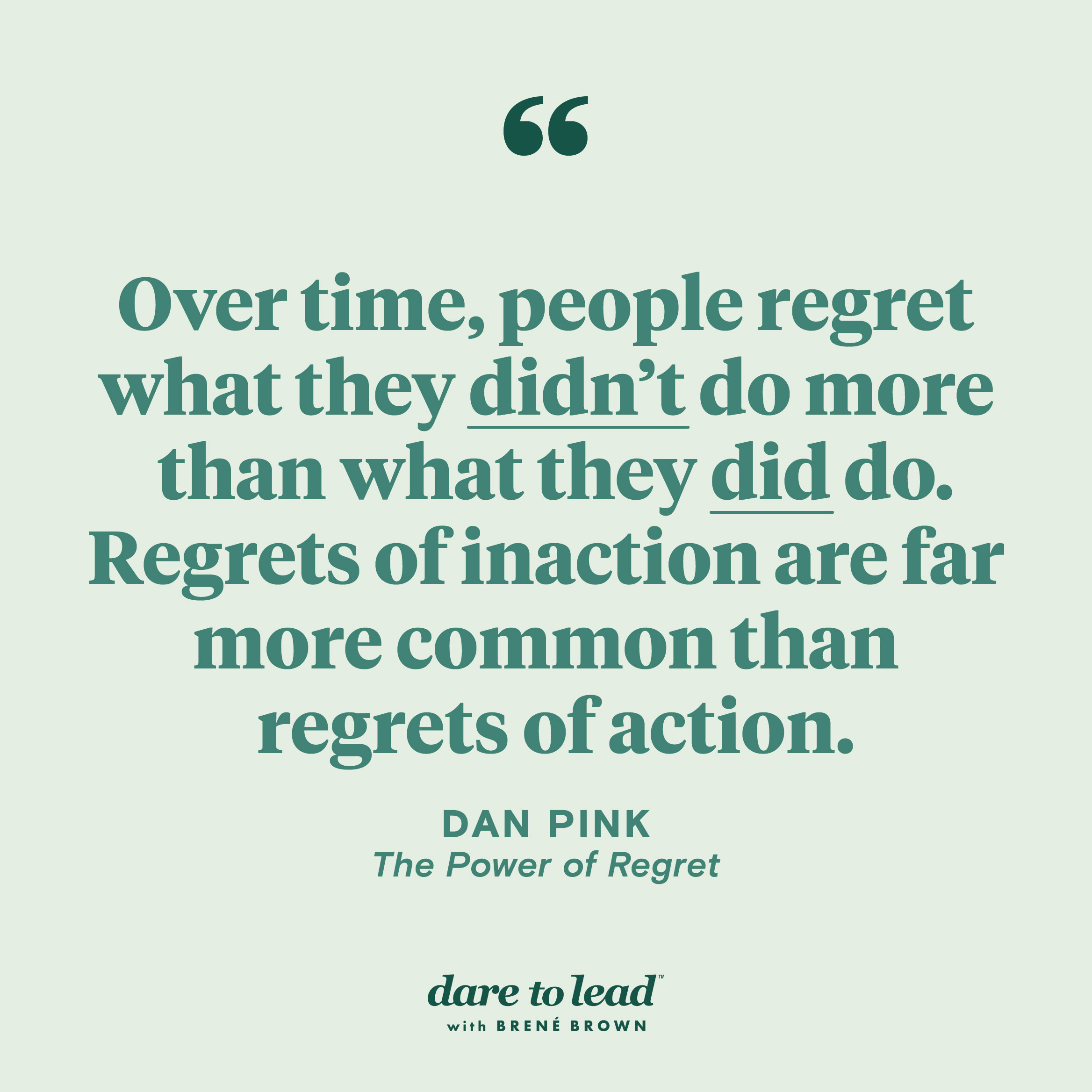

DP: What they regret is failures of boldness, period. Now, again, they don’t necessarily use the word bold, but they’re not singing the same lyrics, but they’re playing the exact same melody in this, that’s the key… As a metaphor to understand that, and the only way you get to that is by reading all these things and having all these voices and stories in your head, and then interviewing all these people and having them pour their heart out to you about something they did years ago that they still feel bad about or something, some kind of tragedy that they’ve actually learned from, and it’s interesting because it’s partly the melody that you’re hearing rather than the lyrics, but if you’re attuned to the melody, you can then describe what that melody is and the melody, in this case were failures of boldness. Now, to your point earlier about the reinforcing ways these things go. This is also consistent with what the academic literature tells us, and also my own quantitative survey, you write about this in your book too, over time, over time, people regret inactions way more than actions.

BB: I’m going to stop you here. This is maybe one of the most key things that I’ve learned, and I want you to teach it to us. Say what you just said again, without question.

DP: Over time, people regret what they didn’t do more than what they did do. That inaction regrets, regrets of inaction are far more common than regrets of action, and this is especially true as people age… One of the things that’s interesting and the demographic differences, which are not vast, this is from my research, is at age 20, people have about the same number of action regrets and inaction regrets, but as they age, it’s all about inaction regrets. And so we end up regretting what we didn’t do, and many of our omissions, are omissions about boldness, omissions about taking the chance, we find ourselves in so many cases in life, Brené, at junctures.

DP: This particular juncture, people, I can play it safe, or I can take the chance, you can play it safe or take a chance, and overwhelmingly, people regret playing it safe more than taking the chance even when the chance doesn’t work out. Now, this tells us something, and as I say in the book, these four core regrets.

DP: They are… Another metaphor here… A photographic negative of the good life, if we understand what people regret the most, we understand what they value the most, so all these 16,000 people think of them, I’m not a musical person, but it’s my second music metaphor here.

BB: I’m with you, bud, I love it.

DP: I wish… I have a regret about not playing a musical instrument, and I’m not alone. I got so many musical instrument regrets, it’s crazy. I had to start taking some out of the book because I was over index on clarinets. So, one of the things that you see is that these four core regrets, including boldness, are the photographic negative of a good life. When people tell you their regrets, their enduring regrets, and they’re all the same over and over again, they tell you what matters most to them out of life. And one of the things that matters to most of us out of life, is doing something, learning, growing, trying stuff, leading a psychologically rich life, that’s who we are. And so to me, what we want to do as a prescription is give ourselves permission to be bold in many ways, but also not put all the onus on individuals, but in organizations, in schools, in churches and synagogues and mosques and community groups, is actually create environments where people feel comfortable being bold. And forgive me for this sermon here, one last word here is that one of the aspects of being bold that surprised me… It wouldn’t surprise you. It surprised me though, and I think it could be gendered here, is that we go into my database together, which could be fun, we go into my database together and we do a search for the phrase spoke up.

DP: Spoken up. Speak up. I regret that I didn’t speak up. I regret that I didn’t speak up, I regret that I hadn’t spoken up when I needed to, I regret that I didn’t use my voice, all of these regrets about people not being bold and simply saying something and asserting themselves and expressing themselves, and I can’t put all the onus on the individual, for that one, you have to put some of the responsibility on the context and the situation that they’re in, and to me, one of the biggest things we can do, again, in all these domains of life is give people the psychological safety and the permission to be appropriately bold.

BB: God, this is just so fascinating. You know this is coming, it’s like you just strap yourself in like, you know this is coming. This is not unconnected to vulnerability and courage, right?

DP: No. It’s not. No.

BB: Tell me more.

DP: Well.

BB: Tell me what you left thinking.

DP: Okay. So, high level thinking, Brené was right. Alright, I can have my three-word… My three-word distillation of it, Brené, I had this conversation today. No joke, the day that you and I are talking about this, I did a virtual event for a very large multi-national company where I was talking about some of the regrets, some of people’s regrets and basically what these core regrets teach us about what people want out of life, but then I also got some questions about how do we process our own regrets, and one of the dimensions by which we process our own regrets is we disclose them.

DP: We disclose them and the research on disclosing… You know it, is powerful, disclosure is an un-burdening, but back to language again, disclosure is also a form of sense-making when we convert these blob-y negative emotions to concrete words, it de-fangs them, it helps us make sense of them. Sonja Lyubomirsky has some brilliant research showing that when we write about negative experiences, we feel better, but when we write about positive experiences, we feel worse, why? Because we lose the thrill and the mystery, so for negative experiences, disclosing them unburdens and makes sense… But here’s the thing, so what I tell these guys, and mostly guys, our fear is that when we disclose failures, setbacks, missteps of our own, we think that people will like us less, and the evidence…

DP: You know this, Brené, I’m preaching to the saved here. The evidence is overwhelming for 30 years of behavioral science, that when we disclose these things, people like us more, and literally today, they respond… So, I was talking about that and “Are you saying that we should be more vulnerable?,” and I wanted to say, literally, “Have you not been paying attention to the last 10 years of this… Come on guys.” And I’m like, “Yeah, I guess so that’s another way to put it,” but anyway, the shorter way to put it is, “Brené was right.” That vulnerability… I’m just repeating. I’m just talking your… I am singing from your…

BB: But this is related to regret, it’s huge. Vulnerability what?

DP: But I’m singing from your hymn book here, you know the vulnerability isn’t a sign of weakness, it’s a sign of strength, it doesn’t make us less, it makes us more, and it’s true with regret, and you can’t process your regrets. You have to be both somewhat soft-hearted but also very hard-headed, so when we think about our regrets, one thing that we should do is we should sort of reframe how we think about ourselves through self-compassion pioneered by your fellow Texan Kristin Neff. Treat ourselves with kindness rather than contempt, recognize that at some level we are not that special. So, if I have a regret about not being kind, I realize that I have to think it’s like, “Well, am I the only one with that kind of regret?” No, I got hundreds of people who have that, disclose them to make sense of them and to un-burden them and to de-fang them, but then also do the hard-headed stuff of self-distancing and extracting a lesson from it that we can apply to the future and the thing is, it’s like we don’t know how to do that, because all of the messages we get are like, think positive, be positive all the time.

DP: Never look backward. And when people have negative emotions, as you write about in the Atlas of emotions, when people have negative emotions, they think there’s something wrong with them, when in fact, everybody has negative emotions, and the most common negative emotion of all is regret, you go after no regrets in your book very, very well. To me, it’s like I’ve done the research, the only people without regrets are five-year-olds, because their brains haven’t developed the dexterity to process regret. No joke. There’s a lot of research in child development about when kids are able to process regret, they are not until they’re seven or eight, the only people without regrets are five-year-olds, people with lesions on the orbital frontal cortex of their brain, some people with Parkinson’s and Huntington’s Disease and sociopaths.

DP: Everybody else has regrets. Not having regrets is a sign often of a grave disorder, and the reason for regret’s presence and for its ubiquity, is that it’s useful. It’s there for a reason. Regrets teach us, they instruct us, they clarify the world for us, if we’re open to receiving them, which is why in your book, you don’t take the, oh never look backward, you say, “You know what, facing regrets requires courage. Having no regrets is not a sign of a life well lived, it’s a sign of a life without reflection.” Bingo.

BB: I have to say that I could give you a list and it would include musical instrument, it would include not being able to play the guitar. Probably, embarrassingly, I’m not unique, but I have to say that the biggest regrets I’ve had in my life that I still have thought about, and I still think about, and boy, have they taught me… It’s like being an ex-smoker… I just can’t even stand the idea of having to quit again, so that’s why I don’t start… I don’t ever want to feel this regret of courage or regret of not being as kind as I could have been for me, those are just like… And I love how you say, just getting the domain list in finance and relationships, and this is so unsatisfying because no matter the domain, it always comes down for me personally, as failures or inadequacies of courage or kindness.

DP: Yeah, that comes out a lot in the research and personally that’s definitely true for me, but give me an example of one of your regrets of kindness, because that’s one of the things that bugs me, Brené, when I look at my own regrets is, especially earlier in my life, I was not nearly as kind of a person as I could have been, and I wasn’t a bully either in some ways, that’s worse, that I was sort of unkind by inaction. But tell me one of your kindness regrets…

BB: Well, I can tell you that I’m talking about the commencement address quote that I use and when I write about regret.

DP: The George Saunders.

BB: Yeah.

DP: I love George Saunders, and that speech is brilliant.

BB: He just said something like, what I regret most are failures of kindness when someone in front of me was being mistreated, and even if I wasn’t the person doing it, that I didn’t just… Not just say something, but just rush to say something, and so I think there have been moments in my life, high school, early career, where I saw someone getting just put down or humiliated and out of my own fear… I didn’t participate in it and I didn’t drive it. But I didn’t step in and say like, “This is so messed up.” And I have to say that I was not raised in a family where no regrets was the rule. It probably has to do with being raised Catholic. We had to think about stuff that we had done, we had to think about how it might made us feel, and then what path are you going to take… To not feel that way again. And so, I would say very early in my life, I was the person, even in my 20s when I was waiting tables and bartending and there were hostile environments, if something was sexist or hurtful, I’d be like…

BB: Not even toward me, I’d be like, “Oh no, no, I’m not watching this.” And this is bullshit. And what are we going to do about this? I regret times where I have been blaming and hurtful to people because I’m afraid, so it’s taken me until I was 50 to understand how scary I can be when I’m scared as a leader… As a parent, as a partner. And when I get scared, I scramble and can blame, and I regret that, I regret being shitty to my husband when I’m scared about work stuff, but help me understand this, be my therapist, Dan.

DP: Completely unlicensed and untrained, and unqualified, but I’m here to serve.

BB: But you were a West Wing political speech writer, so I feel like we’re ready. I almost hate calling it regret, but it is regret, I know a lot about the affect and I know a lot about the neurobiology of the affect, it is 100% regret, but I don’t call it that because somehow I feel like that word has been pathologized, but it is regret. I’m going to tell you this, I’ve never said this before, there was something I read in your book, page eight, “Regret is not dangerous or abnormal, a deviation from the steady path to happiness. It’s healthy and universal. It’s an integral part of being human. Regret is also valuable. It clarifies it instructs. Done right, it needn’t drag us down, it can lift us up.” I have regrets, to be honest with you, from last week, I regret firing off an email to my kid’s school when I saw the number of COVID cases and they’re not doing mandatory mask wearing, and I regret how I handled that, and so I’m not ashamed of it. I’m not embarrassed by it, but I firmly believe that regret is a function of empathy. And when I think about how I did it, today, I didn’t fire off another email, but I wrote it and I started with…

BB: “You all have done an incredible job managing this, I don’t know how you’ve handled it so well that you have. Proud for my kid to go to a school that’s been this thoughtful… Can you help me understand some of the decisions you’re making?” But that email, which I got back an email right away saying, “You’re the only parent that talks to us this way.” But that email that I wrote was completely fueled by the lessons of regret. Explain that to me.

DP: This is why regret exists, regret teaches us if we’re open to the teaching. The problem is, is that regret also hurts a little bit. It hurts and it teaches. But you can’t have just one. So, in your case, this is textbook of how you deal with your regret, you felt that spear of pain, that negative, “Oh my God, I can’t believe I did that, if only I hadn’t been such an ass.” Right, so you have two choices there, you can say, “Ignore it. I ignore it.” Boost to your self-esteem. “I lost him anyway, I’m the king.” Or you can say, “Oh my God, I’m the worst person in the world.” You can just spin yourself up, “Oh my God, I can’t believe I did that” and ruminate over it, or you can think about it… Right? And to me, we haven’t been taught how to process our negative feelings. Some of us are taught ignore your negative feelings, some of us are taught negative feelings are the only truth, wallow in them, and to my view is that negative feelings are for thinking, negative feelings are signals from the world trying to tell us something, and what happened in your case is that it was a negative feeling, they’re trying to tell you something, saying, “You know what.”

DP: “A. That was not empathetic to these people who are working very hard, and B, it was actually an ineffective way to get done what I hope to get done.” However, you disclosed that, you forgave yourself a little bit, you disclosed it, you made sense of it, and you extracted a lesson from it, and that lesson always begins next time, and then the next time you apply that lesson, that is how human beings grow and learn and that’s why regret is powerful if you had taken another route, you would not have learned and grown, and that’s why this is why there’s research from all the way back from the 1980s showing that you record people’s conversations and identify the emotions that they express, and the most common negative emotion is regret, and the second most common emotion of any kind is regret, the only thing mentioned more often than regret is love, and… There’s got to be a reason for that, why?

BB: Wow.

DP: Regret serves a purpose. It serves a purpose, and you’re telling a story of how regret instructed you.

BB: It’s socially adaptive.

DP: And you became better as a result of that.

BB: It’s socially adaptive.

DP: Adaptive, exactly, I mean, Let’s geek out on evolutionary biology, evolution psychology, it’s adaptive, it wouldn’t exist as a trait unless it had some kind of function. And here’s the thing, you write about this in your taxonomy of all these different kinds of emotions that we feel, but we have to have some negative emotions, we should have more positive emotions… Positive emotions are great. They make life worth living. We want to have more positive emotions than negative emotions, but negative emotions need to be part of our portfolio because they teach us if we respond to them appropriately, and I’m convinced that we know how to respond to it appropriately, we just haven’t been taught… And the process is very, very simple.

BB: I love that. I have to say this. I’m going to say something, and you say true or false.

DP: Okay.

BB: Regret is difficult when you struggle with a fragile ego.

DP: True. Would you like me to… I can elaborate, but I like the true false game… Yeah.

BB: Yeah, no elaborate, and then I’ll have another true false for you.

DP: Okay, so I think that the fragile ego is something that self-compassion can address, because here’s the thing, I just want to clarify this for everybody whose feelings are about to get hurt, you’re all very special, alright? However… You’re not that special. Alright, your experiences often are not wildly different from other people’s experiences, and so sometimes when we think about our regret, we say, “Oh my God, I must be the only one who has ever had a failure of kindness, I must be the only one, I’m so unique and special, I’m the only one who had a failure of courage, a failure of kindness,” and that’s such a threat to our ego, we just bat it away, when in fact, if you say, “You know what, maybe being unkind is part of the human condition occasionally, maybe it’s part of the broader human experience,” maybe you’re kind of like other people, and what you should do is just treat yourself with kindness and try to extract a lesson from it rather than protect your ego.

BB: God, you’re remaking regret, so you’ve got self-disclosure, and you talk about Jamie Pennebaker’s work at UT.

DP: All roads lead to Austin.

BB: I mean, hook ‘em horns, baby, let’s just call it what it is. Kristin Neff, self-compassion and self-distancing, so you’re saying, “You’ve got a regret, self-disclose, just be honest about it, because let me tell you something, this is where I love this intersection of your work on regret and my work. Regret can slide into shame. Do you agree?

DP: Absolutely.

BB: Shame needs three things to grow exponentially. Secrecy, silence, and judgment.

DP: Boom.

BB: Shame cannot survive your remaking regret approach. If someone did what you’re recommending in the book, shame actually cannot hang on, because first of all, self-disclosure shame is like, “Shut up, do not talk about this regret.”

DP: That takes on the secrecy leg, we now got the secrecy leg. Now we get two legs left.

BB: Right, and then you’ve got self-compassion, which is the opposite of judgment.

DP: Absolutely.

BB: Yeah, so instead of saying, “God, I’m such an asshole, I can’t believe I fired off that email,” I’m like, “You know what? You’re scary when you’re scared, and you’re scared.” Everyone else is scared right now, kids going back to school. Is it okay? Is it not? Like, it’s alright, and this is everybody. And then the self-distancing, which is really… One of the things I love about Neff’s work on self-compassion is her definition of mindfulness, because a lot of people say mindfulness is like you’ve got to… Don’t ignore the feeling. Feel it. Check, I agree. But then Kristin Neff comes back and says, “But don’t get stuck in it either y’all.”

DP: Absolutely.

BB: And so then you go to Ethan Kross’s work at Michigan, which is, pull out of the amygdala and think about what’s happening. Not feel what’s happening. Don’t become the wound. Think about the wound. It’s so smart.

DP: But I think it’s the way to do things. And you’ve been trying to help people overcome shame, which is in many ways more debilitating than regret, because shame is… You’ve written this beautifully. It’s about who you are as a person more than it’s your act. Regret is about a particular action, it can spin into self-loading about your being, but shame is really about who I am as a person, and that’s why it can be so debilitating, but again, I really believe, Brené, that… And maybe the pandemic is going to force our hand here, is that we just haven’t been taught.

DP: About how to deal with negative emotions.

BB: We really haven’t.

DP: So, people get captured by them, they either live in denial saying, “No regrets, no no no,” or they get completely debilitated by them, and I think it’s because America especially… Yeah, positive thinking. Don’t worry, be happy, smile, smile, smile. And I do think that there’s a kind of gurgling thing, and maybe you started the tsunami with the talk about vulnerability, kind of saying, “Wait a second, maybe we need to rethink how positive we’re going to be,” positivity is good, but you need a little negativity because negativity teaches us and it makes us better and whole.

BB: The thing I say about regret all the time as it is a fair but tough teacher.

DP: Absolutely, absolutely.

BB: That’s just it. I love this book.

DP: But, I love that metaphor. Actually, I wish I had used that. No, but I mean that, very seriously. So, let’s anthropomorphize, forgive my 50-cent word. Yeah, let’s anthropomorphize regret. A regret comes to us, who is regret, you could say, “This regret is a meaningless stranger whom I can ignore…” Alright. That’s ignoring it. On the other hand, you could say, “This regret is St. Peter at Heaven’s Gate, passing judgment on my value as a human being,” or you can say, “This regret is a teacher… This regret is Mrs. Williams in third grade, who’s teaching us how to do math.” And if you think about regret as your teacher rather than as a stranger or rather than as your judger, then it can be very, very healthy. And I should have put that in the book.

BB: I love what we’re doing here because I do think regret is not just a teacher, but it’s the teacher that has your best interests in mind.

DP: Agreed.

BB: So is going to grade your paper pretty ruthlessly because… Not because they’re mean, but because they believe in your talent. I do, I think it’s the best kind of teacher.

DP: I love that. I love that. So, what’s your advice on getting people to reframe regret as a teacher? I think you’re right, when you said earlier that we sometimes pathologist regret the very word, we don’t like to talk about it. When I did this quantitative piece of research, I asked people a question about regret without using the R word. I asked 4,400 Americans, how often do you look back on your life and wish you had done things differently? And we had 1% say never. We had 83% say they do it at least occasionally, and because I didn’t say the word regret, if I said how often you have regrets, you would have this kind of instinctive… “I don’t have any regrets. I don’t have any regrets.” Because we pathologize the word. Now question to you, how do you help people see that that figure coming to them with that label regret, is not a meaningless stranger and is not a judger, but is a teacher?

BB: This conversation, your book. That’s how you do it. You know, as someone who has taken on shame and vulnerability, which people are like, “Ewww.” That’s why I really want to start with the linguistics piece, because you are a really good teacher.

DP: Well, thanks.

BB: And you do have the ear of a lot of people like… You and I both do a ton of work in organizations, I would say probably 90% of my work is in organizations. Probably the same percentage for you, would you say?

DP: Yeah.

BB: And that’s strategic on my part, because I don’t think you change the world unless you change work, and so this is how you do it, I think you have this book. We have these kind of conversations, but we also try to do things like… One of the things I thought when I was reading your book, and I think we’re going to do this, is we talk about key learnings in our organization, but on a macro organizational level, which is… A lot of people listening to the Dare to Lead podcast. We should talk more frankly about regret when we do end of year key learnings or…

DP: How interesting.

BB: I’ll tell you why, because key learnings in my experience, whether I’m working with a C-suite in a Fortune 50 company or I’m doing it in my own organization, key learnings are often born of regret, and divorcing regret from key learnings gives us a partial teaching.

DP: Interesting.

BB: It gives us the… What did you say from Chomsky? It gives us the shallow learning…

BB: Yeah, there’s a surface structure and a deep structure.

BB: So, I think in organizations, when we separate key learnings from regrets, we’re not doing the deep work of… these are humans that had emotions around making decisions, and so I think we just have to do what I try to do with vulnerability and a lot of other people do it with vulnerability, which is next time I’m talking to my kids or I’m doing a talk, I’ll say, I have a ton of regrets, some old… That I’ve worked through this way, and talk about your book and some from last week, and I don’t want to ever stop having regrets because I never want to stop learning.

DP: Right. Amen. Amen.

BB: And I think that’s it. And I think if we can tie regret with learning, and I’ll be honest with you, this is something I feel like I should get off the podcast and say, but I’m just going to say it on the podcast. And how people draw a line between no regrets and fragility and ego is important, because the future belongs to the curious and to the learners, not the knowers, and part of being a learner is having the courage to feel the frisson of regret.

DP: Exactly the discomfort. That’s exactly right. And it’s what I was saying before, it doesn’t feel good and it teaches, but you’ve got to have them both… It’s a combo platter.

BB: It’s a combo platter. Let me tell you what else doesn’t feel good, my squats don’t feel good, my lunges don’t feel good, my effin push-ups don’t feel good. I can do a half one, but I’m building a muscle, and I think regret can be a muscle. You know what I mean? That we have to build, in addition to telling everybody I know to get this book and us reading it as an organization, I’m going to not back off using the word regret when I talk about my own.

DP: Well, Brené I think that would be a big thing. And honestly, and I do think that what you did on vulnerability as a model for that. Can I tell you something?

BB: Sure.

DP: How I got to this… So, I was struggling while I was writing this book, early on when I was writing this book, I was really struggling. I’d come to my office, I just spin my wheels, I get nothing done. A week would go by, two weeks would go by and I just… Struggling. And it got so bad that I reached out to some friends and said, “You know what, I think I need a coach, I need somebody to talk to, I need a coach to help me get my car into this rut.” And so a friend of mine who’s a former executive, knows all these executive coaches and things like that, says, “I’ve got the guy for you. So, she put me in touch with this guy and he said, “I don’t really do much coaching anymore, but I’m happy to talk to you.” So, he talked to me and I told him what was going on. And literally 15 minutes into the conversation, he said, “You don’t have a purpose”

DP: “You don’t know why you’re doing this.” And I was like, “What? Of course, I know why I’m doing this.” He said, “So, we don’t need to talk anymore, what I need you to do is I need you to write me an email, just in a few sentences, just telling me the purpose of this book that you’re writing,” and I was like, “Oh man, I’m having a hard enough time writing and you’re going to give me another writing assignment. What the heck, who are you?”

BB: That’s low. That’s low.

DP: And so, it takes me like three weeks, but I’m thinking about it the whole time, and I finally realized what it was, and it was so powerful to me that I sent him the email, he said “Okay, now we’re talking.” And I actually posted the email for you, I’m reaching over right here in my office, and what I say is, and this is the word, the verb that I’m going to use here is, the purpose of this book is to reclaim regret as an indispensable emotion, and what you’ve done with vulnerability is reclaim vulnerability as something essential to the human experience and powerful for making our lives better, and I am your fast follower on this linguistically. What Brené did for… I should have done this in the pitch for the book now that I think about it… Oh my God, I got to write this down. No, seriously, what you did for vulnerability, I’m realizing in this conversation is what I’m trying to do with regret, is reclaim it… It’s been claimed by people who don’t understand it. I want to reclaim it for the rest of us, so we can use it as a powerful force for forward progress.

BB: God dang, I got goosebumps. Yes, people are like… “Dan and Brené have gone into some kind of vortex and we’re just watching now,” but…

DP: Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah.

BB: I love it.

DP: We’re in some kind of cave somewhere, listening to our own echoes at this point, but I’m enjoying it.

BB: Me too. Yeah, and luckily, it’s my podcast.

DP: This is the first podcast I have done in a while where I’m taking notes, as you can see here.

BB: Okay, so here’s what I think. Vulnerability… The mythology about vulnerability, the primary mythology is really tough, which is… Vulnerability is weakness. Yes, and so I think the work ahead of you around regret is not just what is regret and why is it important and good, but it starts with dispelling the bullshit about it. What you’re up against is this kind of whole YOLO, no regrets, kick-ass, and it’s faux courage wrapped in fragility.

DP: Well, said. You’re the model. No bullshit, you’re the model because you won back… And I mean this you won back… How did you win back vulnerability? How do you reclaim vulnerability? One conversation at a time.

BB: One conversation at a time.

DP: It’s not like you send out an email blast to 10,000 people or posted something on social media. How do you win it back? You win it back one conversation at a time, and because you started those tens of hundreds of thousands of conversations about vulnerability people’s lives are better, if I can do something like that with regret, this teacher, then I could feel pretty good about this latest project.

BB: I’m cheering you on, and I’m going to participate when you ask… I love it.

DP: Thank you.

BB: You ready for rapid fire?

DP: Oh Yeah.

BB: Fill in the blank. Vulnerability is…

DP: Essential.

BB: Okay, this is a good one. What is one piece of leadership advice that you’ve been given that’s so remarkable, you need to share it with us or so shitty, you need to warn us…

DP: I had somebody who was higher up in an organization, I don’t want to reveal anything more of this, who criticized me, who basically took me aside and said that I was doing it wrong because I was in his words, kissing down and kicking up, that I was treating people below me too well, and people above me without enough deference and that was the wrong way to do it.

BB: I’m assuming this is going in the shitty side of this thing…

DP: Oh yeah, absolutely, go on. I’m sorry if I didn’t make that clear. Yeah, no, I mean, that was like. Whoa.

BB: That is like…

DP: Okay, I’m sorry, you just said the quiet part out loud, aren’t you ashamed of that?

BB: Okay, that’s so good. Okay, here’s a good one, what’s the hard leadership lesson that you have to keep learning and unlearning and re-learning that lesson that the universe just keeps putting in front of you.

DP: That everybody doesn’t see the world the way I see it, and doesn’t have the same view of quality or excellence or speed, or goodness, and that they’re not wrong, they’re just different in the way that blue is not a better color than yellow, it’s just a different color than yellow. And sometimes I’m mystified that people don’t see the world exactly as I do, and I shake my head and then say, “Okay, here we go again… Universe, sorry, that’s right.” My wife even says that to me when I start a conversation about something and she says, “I have no idea what you’re talking about, I’m not in your head,” and so recognizing that people are not in your head is something that I’ve tried to get better at, but I’ve learned it a lot over and over, I’ve learned it this week.

BB: Oh God, it’s hard. Alright, what’s one thing that you’re really excited about right now?

DP: I am really excited that my son is in his freshman year of college and seems to be having a great time, that my middle daughter is in her first job and is flourishing, and that my elder daughter is applying to graduate school and about to enter a different chapter of her life.

BB: Oh my God, those are so good. Tell me one thing you’re deeply grateful for right now.

DP: I mean, I don’t want to sound cliche. My wife. It is unimaginable to me. My life without my wife, there’s some interesting research on, well, I’m going to drain the emotion out of it, so I can actually talk about it without cracking, but there’s this technique called the mental subtraction of positive events, where you feel better about your situation. When you imagine what your life would have been like had something good not happened, it’s sort of the George Bailey… It’s a Wonderful Life technique, and I truly am grateful for Jessica every single day, and I mean that consciously… I’m not saying that to bullshit, I’m saying that because I think about it all the time, I shudder to think what my life would be like without her.

BB: Beautiful. Alright, we asked you for five songs you can’t live without… Let me tell you what, you gave us. “Bad Reputation.”

DP: I love Joan Jett, Joan Jett. I’m going to make a film recommendation to your listeners, there’s a documentary about Joan Jett, it is one of the best music documentaries you’ll ever see, Joan Jett rules.

BB: Wait, wait, wait, I’m a huge Joan Jett fan. So, I love this. Where is the documentary? And what’s it called?

DP: It’s streaming, I think on Netflix or whatever your streaming provider is, and I don’t remember what it’s called, but we’ll put in the show notes.

BB: We’ll put in the show notes. So, first song, “Bad Reputation,” Joan Jett and the Blackhearts. “Fight the Power,” Public Enemy. “I Know What I Know,” by Paul Simon, “Modern Major-General” by W. S. Gilbert and Arthur Sullivan. and “Think,” by Aretha Franklin. In one sentence, what does this mix tape say about Daniel Pink?

DP: Daniel, that’s a good question. Daniel cares about language and he wants to push things a little further along, but do it with good humor.

BB: That’s so good, I was trying to figure out how you were going to weave in Gilbert and Sullivan.

DP: I don’t know how I was going to get out of that. But if I can drain the mystery of it by unpacking so that Gilbert and Sullivan song, “Modern Major-General” is such incredible hilarity and word play. I encourage your listeners, I have it on Spotify, I have it on my playlist on Spotify, it’s like “I am the very model of a modern Major-General. I have information, vegetable, animal, and mineral, I know the queens…” So, it’s a sort of incredible linguistic marvel. But then “Fight the Power” is a brilliant song from late 80s, hip-hop, that was the soundtrack for the movie, Do The Right Thing. And then “I Know What I Know,” one of the best lyrics in all of music, where at the beginning of the song were Paul Simon sings… “She looked me over, I guess she thought it was all right. All right, in a kind of a limited way for an off night.”

BB: That is a great lyric.

DP: I know. But thanks for doing that, that was like the most enjoyable exercise in the last two weeks for me, when your teammate, Gabi said, “We need your five songs,” and I’m like, “What?…” And I’m into this now.

BB: Well, Dan, let’s just say the book is the Power of Regret, How Looking Backward Moves Us Forward, it’s a game changer… And I think there’s so much hard shit going on in the world right now, that if all we do is just barrel forward without pausing and looking back and thinking, “Wow… I don’t feel good about that. What can I learn?” This is the time, and this is not just the time, in my opinion, for individual regret, but organizational thinking, but also community and macro and political. Demystifying and reclaiming regret doesn’t have just interpersonal consequences.

DP: I’m going to give you my seventh amen of our conversation. Amen.

BB: Thank you for being on the podcast.

DP: Thank you for this conversation. It was enlightening and moving, and I have now two pages of notes.

BB: Awesome. I’ve loved this conversation, I loved this podcast conversation, I mean, I don’t need to tell you because you’ve listened to it, if you’re at this point now, hardcore geek out. It had it all, qualitative data, quantitative data, evidence with stories. Data with a soul. This is my wheelhouse here, I love this, you can find Dan’s book, the Power of Regret, wherever you like to buy your books, we’ll also post a link to it on the Dare to Lead episode page on brenebrown.com. You can find Dan online at danpink.com, he’s also on Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook. His handle on all those platforms @danielpink. All that stuff is on the episode page as well, I love the work that he’s doing, I love having a partner in this kind of cultural effort to reclaim regret, I do think it is a tough but fair teacher, the kind we need… And I love the data. Don’t forget that every episode of Dare to Lead has an episode page on brenebrown.com, you can listen to every episode there if you’d like, you can learn more there with resources, downloads, and transcripts, and you can also sign up for our newsletter. As always, everyone can listen to the Dare to Lead podcast on Mondays and Unlocking Us on Wednesdays.

BB: We are on Spotify, and you can also listen on brenebrown.com. Excited that you’re here. Thank you. Stay awkward, brave, and kind.

BB: The Dare to Lead podcast is a Spotify original from Parcast, it’s hosted by me, Brené Brown, produced by Max Cutler, Kristen Acevedo, Carleigh Madden, and Tristan McNeil. And by Weird Lucy Productions. Sound design by Tristan McNeil. And the music is by The Suffers.

[music]

© 2022 Brené Brown Education and Research Group, LLC. All rights reserved.